Half-Life 2’s Animated Architecture

Part of what makes Half-Life 2's level design so interesting is the placement of non-player characters. This article examines how NPCs were used as "alternative architecture" to guide player movement.

Half-Life 2’s first level is pretty unforgettable. Riding the rails into City 17, Gordon Freeman clumsily makes contact with his former colleagues from Black Mesa: Eli Vance, Isaac Kleiner, and Barney Calhoun. Still disoriented by the G-Man’s ominous greeting, he wanders into a dystopian future that’s been co-opted by the Combine. The streets are full of stunstick-wielding soldiers. Freeman doesn’t even have a crowbar. Scarcely any more knowledgeable about this brave new reality than Half-Life 2’s tongue-tied protagonist, how do players know where to go? The answer to this question isn’t quite what you’d expect.

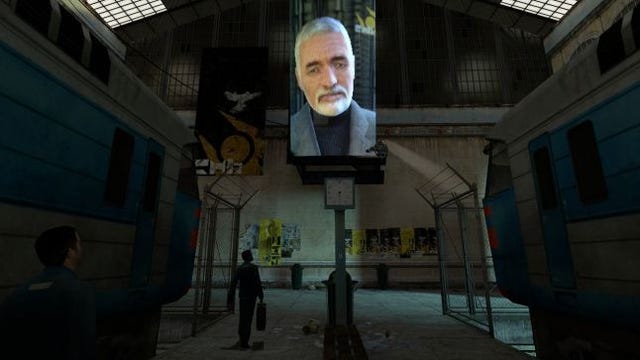

The sinister G-Man introduces Freeman to his new reality

The Combine have been running the show since the Black Mesa incident

Enabling movement in some directions while constraining it in others, architecture is a powerful tool for social control. But how is architecture defined in a game world?

Spoiler alert: the following article contains minor early-game spoilers.

We don’t normally think of people as architecture, but the only real difference between them in a video game is their level of animation. Walls, windows, and doors are static. People move around. Half-Life 2’s opening level explores the possibilities of human architecture by using Combine soldiers to guide player movement. Where in other games you would find only architecture, the developer behind Half-Life 2, Valve, put people. Players can smash through most of its human architecture in later levels, but the game denies you the possibility for combat until Barney throws you that crowbar. The opening level puts players at the mercy of their enemy.

The Combine have three types of solider: walls, doors, and windows. Players come across two of these before ever leaving the train station.

Breen can be found on screens all over City 17

The first thing which you see in City 17 is a ten-foot tall talking head: Wallace Breen. Thankfully there’s a waiting room just around the corner from this friendly face. Walking past a series of chain-link fences, you enter into a three-way junction after leaving the waiting room. Your first instinct is to continue straight ahead, but you’re soon blocked by a soldier with a stunstick and waved aside, so you end up shuffling over towards the sign reading “Nova Prospekt.” Three soldiers quickly hem you in. What exactly is going on here? Forcing players to move in the desired direction, these Combine soldiers are basically just walls. In other words, they keep you on the right track by limiting how much of the game world you can freely explore. These walls can definitely walk and talk, but their function is surprisingly simple: they keep the player moving between story beats. One of them even turns out to be everybody’s best buddy: Barney.

The checkpoint guards are basically walls

You stumble upon the human equivalent of a door shortly after Barney sneaks you past the security checkpoint. Half-Life 2 confronts you with another soldier at the ticket gallery, but this one doesn’t behave quite like the others: he’ll smack you repeatedly with a stunstick until you pick up an empty pop can. This guy’s actually pretty nimble, so he’ll even chase you down the hallway if you look for creative ways to avoid compliance. The only way to make him step aside is to show your commitment to keeping the streets clean. (You can also just run past him). Since all that you’re doing here is changing an object state, this encounter is mechanically no different from opening a door. Players approach the obstacle and perform the required action. Half-Life 2 just makes you do it with more gusto.

Put the can into the recycling bin to continue

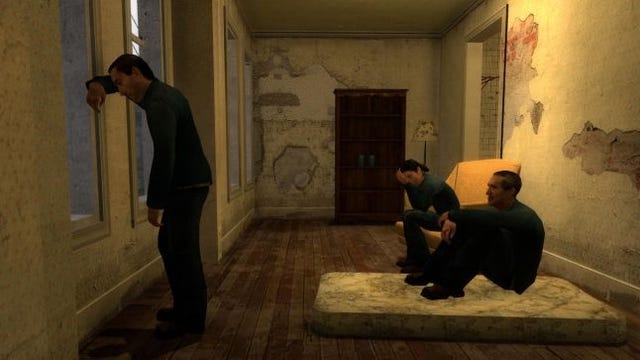

The game lets you explore City 17 a bit after the train station, but you’ll eventually find yourself in a rather nasty tenement building. Things are calm until some Combine soldiers break down the door and start rounding people up. They chase you through a series of apartments, down a hallway, and up a staircase. The cat and mouse continues onto the rooftops. (Good thing Alyx Vance comes along). You’ve already been shown human walls and doors by this point, so the game now presents you with something completely different: windows. You can’t make it past the Combine soldiers, but the civilians will clear a path for your escape when they hear the enemy coming. They do it right on time, too: you actually have to react pretty quickly to avoid the impending beat down. How convenient that a bunch of bots would know just when to step aside?

Things are calm in the tenement building until the Combine come along

Video games are produced under the assumption that all assets are created equal. This means that people are thought about in terms of their function. Their job is to guide players through a level, so people in this respect are no different from walls, doors, or windows. There’s one question though which remains to be answered: what keeps developers from just using walls, doors, and windows? The answer is actually pretty simple. Human architecture enriches the gameplay experience by adding something which the material variety never can: a feeling of depth. Half-Life 2’s human architecture helps the player figure out what it means to live in a world run by the Combine. This involves running up against a lot of human walls and doors, but also finding some open windows.

This article was reproduced from "Half-Life 2's Animated Architecture," posted to SlowRun on March 17, 2018.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)