Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

| Picture Perfect: Exploring Photography Games | ||

| Every day this week, Game Developer is serving up a gallery of interviews, deep dives, and more digging into the evolution of Photography in video games. | ||

| Browse Latest Articles | Submit your Blog | |

As we close out Photography Week, let's talk about some of our favorite photo modes and how they've enhanced our playing experience.

For Photography Week, Game Developer has showcased new interviews, essays, and deep dives demonstrating the creative and technical process behind photography games and photo modes. In this group blog, join us as our editors ruminate on the photos and photo modes they love and explore their evolution and their value within the medium.

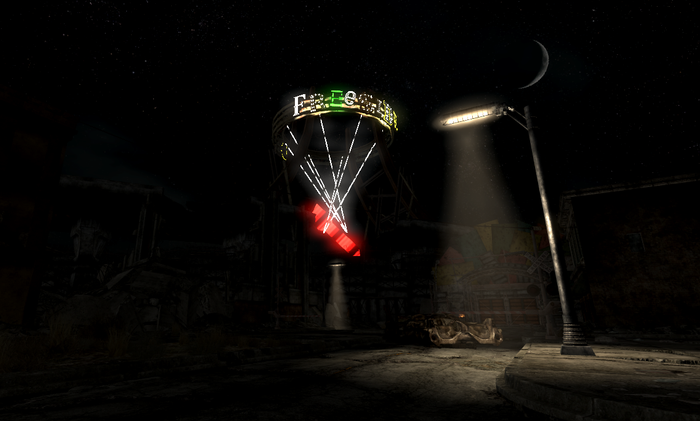

It’s so funny how it doesn’t matter if you’re a traditional photographer, or just like taking a lot of screenshots in video games—looking back at your early work is always so humbling. I recall taking these photos (including the header of this article) in Fallout: New Vegas and being proud of them. So proud, in fact, that I hung on to them for years. It wasn’t actually that hard to find them, only one external storage device deep on my PC, 14 years and at least four hard drives later.

The Western Sky mod for Fallout: New Vegas deeply altered the day and night cycle, rendering certain hours of the day pitch black, both a strategic and photographic opportunity.

I remember that taking photos in Fallout: New Vegas was as much about enjoying the scenery as it was spending more time in the game. I didn’t actually like New Vegas at first; it wasn’t as dark as Fallout 3 and I wasn’t fond of how its cool greens and grays were replaced by the bright orange palette of the Mojave. A Nexus mod, Western Sky, actually changed my mind, adding dynamic lighting and weather effects that turned the environment hostile but also strangely beautiful, with pitch-black nights and intense blue skies and rad storms that would pummel the Courier into the sand. The mod not only had the effect of making the game more strategically interesting, but visually as well.

It was the early Bethesda Fallout games that gave me the training wheels to move onto “real” photography; back then you’d use the console commands to quickly detach the camera and remove clipping, and with that, capture moments from the game at more dynamic angles. While not exactly as sophisticated of the photo modes today, or heck, even the Bethesda photo modes of today, it’s an experience I remember fondly for how much it did teach me about the basics. Take away the ability to consider fundamental things like depth of field and you’re left no option but to be in the moment and take in every detail within a tiny field of view that occupies that microscopic sliver of time. That it’s in a video game doesn’t make at any less an exercise in observation.

That observation process can offer a lot of solitude and contemplation. It demands rumination and self-reflection even as it commands you be present to the exclusion of everything else. Maybe that’s why taking photos in Fallout: New Vegas felt so good. Documenting the journey of the Courier as they crossed so much desert on foot and encountered so much uncertainty and decay and emptiness became a mirror not just of their loneliness and isolation but also my own.

These days I still take the occasional snap in Fallout. Fallout 76 has a dedicated photo mode that combines traditional camera and photo editing features, letting you control depth of field, field of view, and lighting, and add player poses or picture frames. Unlike New Vegas or Fallout 3, it’s also easy to get more variety in your shots, as 76 is comprised of regional environments with dramatically different enemies, plants, weather and lighting.

But the improvements haven’t resulted in me taking more photos, despite how easy it would be to create my own scene with the game’s workshop tools. Maybe it’s just harder to find a moment of contemplation in a crowded live service game with so many random people looking over your shoulder.

Still, it’s nice to remember how mods and PC console commands paved the way. —Holly Green

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

I've recently fallen all the way down into a Dredge-shaped Abyss. While I've been excited about the game ever since its launch last year, I never put much time into it until the last couple of weeks—and knowing photo week was coming up gave me the perfect excuse to dive in fully.

I love the game—its compelling core loop of fishing, exploring, building your boat up to get better at all of the above (spiced with dodging unfathomable horrors), its slow burn Eldritch horror story and impeccable, salty vibes. It's also often a weirdly beautiful game despite its subject matter and increasingly horrific sea life. There's an aching loneliness to the player's journey that is constantly pierced by the ambient (not-mutated) critters splashing about: sea turtles shimmering in pairs, dolphins bounding playfully, whales surfacing briefly, subjecting you to a tiny little touch of majesty every now and then.

It works in conjunction with the sky, the sea, the rough hewn little bits or architecture that people have eked out in this nightmare world. Your little boat, always a bit cartoonish and never a match for anything that lurks in the deep—but you keep going anyway. And every now and then, you get treated to a view like this one.

It all seems to say sure, you're just a tiny speck in this terrifying, unknowable ocean. And on top of nature's indifference, there are creatures in the deep waiting to get at you, for harboring some of that forbidden knowledge humans should never have. But at least you aren't alone out there in infinity. Some beauty still remains. —Danielle Riendeau

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Photography is a beautiful lie. Every photo you've ever seen isn't a snapshot of reality, it's light channeled through a lens, slapped onto a sensor or strip of film, and processed before becoming the image you see in the real world. That image is shaped by the aperture of the lens, the speed that the shutter clicks, and the "stock" of the medium the light lands on.

I love that lie. In-game photography tools make it so easy to easy play with, and it brings players close to the little lies that make games possible. When you freeze the world and muck around with artificial camera settings, you catch things developers don't want to be seen. But instead of killing the fantasy, it invites you to play with the lie yourself—especially when posing a character. I love juking the controls before smashing the "photo mode" button to move a character into the right pose, using an in-between frame to turn a simple transitional motion into a bit of storytelling that captures the "vibe" of the game.

I call it a "lie," like it's a bad thing, but everyone knows a games are full of lies. Photo modes bring players in on the lie, and remind us these lies aren't meant to harm, but to help us speak in a language that goes beyond words. And I just think that's kind of neat. —Bryant Francis

You May Also Like