Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In his first article, Badgeville's Tony Ventrice identified seven ways in which games create fun as a map toward gamification -- and in this follow-up article, Ventrice delves into the first two of his seven identified dynamics of game design.

[In the first installment of this series, Badgeville's Tony Ventrice looked to frame the discussion around what's possible with gamification by attempting to discover what makes games fun. In this article, Ventrice delves into the first two of his seven identified dynamics of game design.]

Growth describes a sense of direction and progress. It is a fundamental aspect of humanity, the first great challenge of adulthood, and a typical source of midlife crisis. When you ask a child what they want to be when they grow up, you're asking about their plan, their direction for life. When, old and shrunken, you look back over your life, satisfaction lies in what you've accomplished. Where did you start and where did you end up? When all is said and done, our entire existence is summed up as a story of growth.

Types of Growth

Growth comes in different guises, and depending on what you value and where you are in life, the ways in which you seek and measure growth will be different.

Children

For children, growth is literal: from the physical growth of their bodies to their gradual accumulation of adult privilege and responsibility, they are effectively growing to become "complete" and functioning adults.

Adults

But what happens when a child is all grown up? How does the definition of the word change? What is the meaning of growth for adults?

Even from a young age, children begin to supplement their literal growth with other forms -- things like an expansion of knowledge, a record of accomplishments, an accumulation of order, and a network of friends. Once the body stops growing, and the basic rules of society are understood, the pursuit of these other dimensions continues, guiding us through the rest of our lives.

Not only do these other forms of growth provide individual motivation, they are, in many ways, the underpinning of our societies. Our desire for learning solves problems; our desire for competition challenges stagnation and finds optimizations; our desire for order preserves and protects; and our desire for connections promotes cooperation and bonds us together.

Now, most people probably never catalog their accomplishments by category, and there's certainly no universally recognized list of measures, but I believe the four I've listed are fairly comprehensive -- and if you bear with me a little longer, I'll try to illustrate why.

The four basic types of adult growth:

learning

order

challenges overcome

connections

A Realization

While thinking about the measures of growth, I realized the list I was making resembled some other lists I've seen before -- namely the Bartle test, the Myers-Briggs personality type indicator, the four humors of antiquity, or really any other form of personality classification system. Yet these systems tend to focus on determining personality types. Could it be that they also identify the general preferences along which people strive for growth?

Bartle | Meyers-Briggs simplification | Beatle | Growth preferences |

|---|---|---|---|

Explorers | Thinking Introverts | George | seek questions and learning |

Achievers | Feeling Introverts | Paul | seek order, balance and validation |

Killers | Thinking Extroverts | John | seek competition and challenges |

Socializers | Feeling Extroverts | Ringo | seek interactions and connections |

While useful to understanding possible differences between individuals, I think these designations have always been potentially misleading when thought of as attributes or archetypes (such as the implication of the Beatles example). As attributes, there is a tendency to think only in terms of differences, but when considered as motivations, it's easier to think of these four "types" as actually being present to varying degrees in all humans. In other words, an individual probably values one form of growth more than another but ultimately they're all valuable, in some degree, to everyone.

How do these four forms of growth manifest in game design?

Learning. Learning comes from deciphering the rules of a system. Typically, this follows a pattern of trial and error, forming hypotheses and testing them within the game environment.

Learning. Learning comes from deciphering the rules of a system. Typically, this follows a pattern of trial and error, forming hypotheses and testing them within the game environment.

To take a game like Street Fighter II as an example, the learning is in first mastering each move, then discovering effective combos, and finally identifying the best situational opportunities in which to use them.

Although learning is a means towards a competitive edge, it can also be a pleasurable end in itself; learning simply for the sake of the process. Why is the card game Bridge so widely appealing? Is it because there is always something more to learn?

Order. Order may seem like an odd way of defining growth, but I think it makes more sense if thought of from the perspective of rules.

There is a basic human desire to believe life has meaning and purpose and for this to be true, there must be implicit rules -- concepts of correct and incorrect behavior. As a dimension of personal growth, order represents pursuit of following the correct path, however the individual may choose to define it.

In most video games, the motivation of order boils down to the act of following rules for rewards: collecting sets, completing tasks and leveling up. Those who seek order desire situations where the rules are clear and simple adherence is all that is needed to succeed. They prefer frequent and literal validation that the system functions and that it is guiding them towards a greater objective or higher status.

Challenges Overcome. If some thrive in order, others thrive in chaos. Life is constantly challenging and humans must adapt to survive against adversity. While the process may be exhilarating, it can also be painful and unpleasant; in real life, many challenges cannot be overcome at all, leading to discouragement.

Games offer a pleasant escape in that the challenges they present are almost always surmountable. In fact, if they aren't, your design probably has a serious problem. The difficulty with implementing challenge comes in the balance: too easy and it's not challenging, too hard and it's discouraging. Challenge-driven players need a regular cycle of challenge and success.

Connections. As Donne wrote, no man is an island. Making connections and sustaining relationships is deeply ingrained in all spheres of our lives and underlies our very concepts of civilization and society.

In games, social growth manifests as interdependencies -- people who need you and people you need. From World of Warcraft raids to CityVille gift exchanges, the more connections and the deeper the dependencies, the more rewarding the experience will be to the socially-driven player.

To investigate how growth might be integrated into a non-game environment, we'll look at each motivator in a general context.

Implementing Learning. Learning requires only a system of rules. Any system could suffice, but obviously the more nuanced and subtly deep, the longer learning will be sustained.

Unfortunately, there is an additional complication: the learning curve. Different users learn at different rates, and if you don't want to lose audience, the learning needs to accommodate a flexible rate of uptake. An ideal learning curve provides a simple basic layer of interaction with the opportunity for deeper emergent layers (strategies, situational rule changes, etc).

In general, you do not need to design to add learning; you need to design to manage the learning you already have. Try to simplify the required learning and push complexity into "end game" objectives for your more advanced users.

Supplementally, challenges and game trivia can be entertaining and validating for the learning process, if handled unobtrusively.

Implementing Order. This is where badges, trophies, and the current idea of "gamification" has already bridged the span from game to non-game experiences. Badge-based systems are not new; from children receiving gold stars for turning in their homework to military officers receiving chevrons on their shoulders, they are a familiar construct.

Any meaningful experience can be commemorated with symbolic measures and, for additional validation, badges can be linked to rewards or privileges. For example, gold stars might result in candy bars, while chevrons bring rank an increased chain of command.

Implementing Challenges Overcome. Here we're talking about the goal of overcoming opposition. The user wants feel magnitude and relevance -- that his accomplishments are rare and special.

Yet in reality it's logistically impossible for everyone to be exceptional. In a solo experience, where the player has no frame of reference as to how other players are doing, this isn't a problem, as it's not necessary to prove the magnitude of a victory. The game feels challenging, and there is no reason to think that it isn't.

I'd say this sense of challenges overcome is the one thing, more than any other, traditional video games have relied on for fun so far.

In social environments, where players can compare progress, the weight of accomplishments may be devalued. If I complete a difficult challenge only to discover that most people achieved the same result in less time or fewer attempts, much of the fun of the accomplishment is lost.

To maintain the illusion, more complex strategies are needed. Strategies such as 'framing' victory (you're the best over-forty, overtime, free-throw shooter) or simply sidestepping the problem entirely with misleading implications, such as letting both players in a competition think they're winning (I'm looking at you, Empires and Allies).

If deception isn't desirable, the best option is probably a mixed approach of solo and social challenges, with lots of little non-competitive victories to get users hooked, leading up to harder, more socially-contestable victories at the top: aspirational objectives to keep the most competitive achievers engaged.

Implementing Social Growth. There are a few provisions needed to foster social growth. First, there need to be venues of communication and collaboration. If players can't talk to each other and interact in any meaningful manner, there's no opportunity to make social connections.

Second, there needs to be a context, a social objective or at least a conversation starter.

Third, there needs to be persistence. Players need to be able to reconnect with the same people.

It should come as no surprise that these three are perhaps most clearly demonstrated by social networks, such as Facebook. Wall posts, messages, tags and comments constitute venues of communication, status updates and shares constitute context and the network itself represents persistent connections.

Intrinsic Motivators

When viewed collectively, the four motivations of growth often comprise a player's most basic intrinsic motivations -- motivations that the player carries with him into every context, be it a game, a job or an evening with friends. These are the motivations that, when actualized, are central to providing the long-term interest that keeps people engaged.

Emotion is potentially a vague or equivocal topic and worthy of a little investigation before we dive right in to defining what makes it fun.

Enlightened thinkers have been making lists of "primary" emotions for a long time, with some well-known names including Descartes and Hobbes. And while lists are interesting, typically, they haven't agreed on much beyond the fact that humans experience pleasure, pain, and some other stuff.

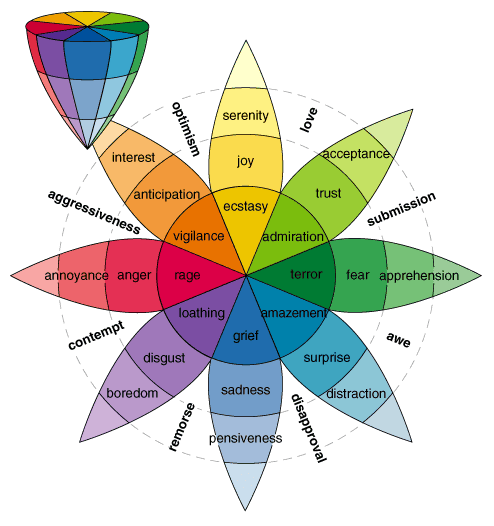

Fast-forwarding to the present, the situation doesn't seem to have changed much. Robert Plutchik [PDF link], who is something of a thought leader in the field of emotion, has created an eight-point wheel with four spokes: Anger-Terror, Anticipation-Surprise, Joy-Sadness, and Admiration-Loathing. Plutchik made some questionable choices with his model, like using two dimensions to represent four, placing the axis extremities in the center, and suggesting the whole thing be folded to form a cone.

Probably as no surprise, Plutchik's model largely results in nonsense when you try to put it to practical use -- where might I place jealousy? Pride? Lust? Pity?

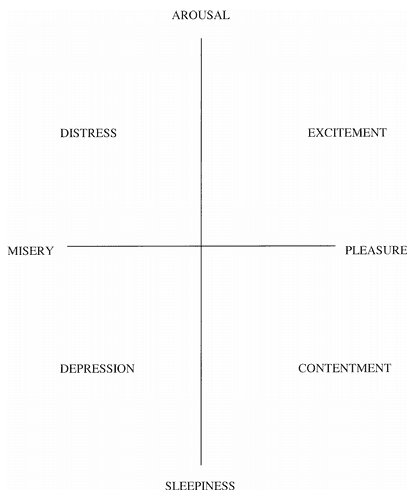

James Russell [PDF link] proposed an alternate model with a much more logical method. His "circumplex" plots eight basic emotions on a two dimensional graph with Arousal to Sleepiness along one axis and Pleasure to Misery along the other. Excitement, Contentment, Depression and Distress are situated in the quadrants between. By limiting all emotion to an arousal scale and a pleasure scale, he at least proposes a measurable system.

While I don't believe there is anything wrong with Russell's model, it seems to be describing a different kind of emotion than the kind we're looking for. Russell's emotion is the primitive kind, the kind reptiles have, and not exactly the kind that is going to explain the appeal of a political satire or a taut thriller.

The fact seems to be, if we want a practical definition beyond a simple measure of pleasure and pain, our science has yet to provide. Fortunately for this investigation, there may be a way of approaching the question from another direction.

Since the dawn of recorded history, the stories we find entertaining have followed a consistent template: genres. And the interesting thing about genres is most of them happen to coincide directly with specific emotions: Suspense, Romance, Comedy, Horror, Adventure, Drama and Tragedy. While this isn't a comprehensive list of human emotion, it does appear to be a comprehensive list of emotions we explicitly seek for entertainment.

In game design, multiple emotions often turn up woven together in complex stories, but for our purposes we'll attempt to address them in isolation, as part of the game experience itself, using the simplest, most pure examples possible.

Suspense (or Thriller) is perhaps the most common emotion in games, and turns up in any game with an uncertain outcome. An entire genre of kids' games (that I like to call "Russian Roulette games") is based entirely on suspense and includes the Water-balloon Toss, Crocodile Dentist, and Don't Wake Daddy.

But more than these, any games that build on anxiety contain suspense, such as children playing hide and seek in a dark house, the card game Slap-Jack, and the aspect of survival horror games in which monsters spring on you from unexpected directions.

Romance has a few representatives that often share duty with suspense; Mystery Date is a weak example, as are likely those dating simulators sold in Japan.

Less vicarious examples include spin the bottle and strip poker; some would argue actual flirting and dating are part of a ritualistic mating game. I would also add that situations where sexual tension might develop in online social games should count (I certainly saw plenty of flirting when I was working on Zynga's poker.)

Comedy is clearly a driving objective of many creativity-based party games like Taboo, Once Upon a Time, Balderdash, and Apples to Apples. The latter two even directly reward humor via voting mechanics.

Yet you probably won't find more than a passing mention of comedy in these game's rules; comedy instead seems to be an emotion just waiting to happen anywhere players are given the context to express themselves in a free format. As evidence, you probably don't have to look any further than the activity of your friends on your Facebook wall to find a series of quips and one-liners.

Horror as entertainment requires a certain terrifying visceral experience that aims to instill disgust and build a sense of dread. While gladiatorial combat was probably quite the spectacle in its time, in the modern era horror as entertainment is largely limited to pure narrative fantasy. Horror games are usually clearly packaged, including the likes of FEAR, Resident Evil, BioShock and Dead Space.

Adventure covers just about every video game featuring a protagonist ever made. The player overcomes adversaries, cheats death, and races against time. In a lot of ways, adventure sits at the intersection of many of the other emotional genres; a little bit thriller, horror, comedy, suspense, and even romance. It covers none of these emotions too deeply, and perhaps this balance is what makes an adventure so universally appealing (and so unlikely to be obtained in simple non-game experiences).

Drama is something of an umbrella term. Dramas tend to cover a range of emotions not already mentioned; things like jealousy, suspicion, honor, guilt, greed, ambition, ennui, and repression. Collectively, they seem to describe interpersonal relations taken to dysfunctional extremes.

Game stories certainly take advantage of drama regularly (any JRPG), but in actual gameplay, games tend to rely on the more competitive aspects like suspicion and ambition. Multiplayer games that require balancing competition and cooperation, like Avalon Hill's Diplomacy, represent the rare few that accurately model the emotional strain of shifting trust, honor and guilt of real drama.

Tragedy seems to be the least-represented emotional genre, with only the rare game dedicated to it (Shadow of the Colossus and Sword and Sworcery are two examples and both play tragedy with subtlety).

Tragedy seems to be the least-represented emotional genre, with only the rare game dedicated to it (Shadow of the Colossus and Sword and Sworcery are two examples and both play tragedy with subtlety).

But this should be expected: to constitute a tragedy, the experience must ultimately be a failure, and failure is not a satisfactory outcome in most game designs. Although it is worth observing that, in most multiplayer games, everyone but the winner ultimately fails, and that in itself is something of a controlled tragedy.

Emotion is a difficult element to instill into games. It tends to be highly contextual and not usually pursued as an explicit objective beyond the scope of traditional story-telling. When considering emotion as a gameplay objective, I think it's beneficial to view the available emotions in three groups of utility:

Those that integrate well with traditional game mechanics: Suspense

Those that can be worked into a design, if the proper considerations are taken: Romance, Comedy, Drama

Those that really only work in the context of a story: Horror, Adventure, Tragedy

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like