Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In the latest of his exploration of different game dynamics which can be harnessed for gamification, Badgeville's Tony Ventrice explores how choice and competition function in games, and how players are affected.

[In the first installment of this series on gamification, Badgeville's Tony Ventrice looked to frame the discussion around what's possible with gamification by attempting to discover what makes games fun. Two dynamics he explored before were Growth and Emotion, and in this article, he tackles Choice and Competition.]

The word "choice" could be defined to describe strategic choices or tactical risks. But those are topics we already covered when we discussed growth, learning, and overcoming challenges. The definition I would like to discuss now is: the freedom to choose and the freedom to act. To put it another way, I'd like to talk about autonomy.

Many of our modern cultures are founded on the concept of autonomy as an inborn right. We give it names like: freedom, liberty, and expression. It is a favorite topic of philosophers, and an investigation of the subject could easily lead to the likes of Locke and Kant, but for our purposes it shouldn't be necessary to go that far.

Instead, I'd like to stick to simple definitions. To start, I think it's safe to say every autonomous choice implies three potential considerations: impulse, influence, and morality. The desire to effect change, understanding the results of that change, and the moral implications of those results.

I'll reiterate that these are possible considerations; a choice need not consider all three, but only a minimum of one (if it considered none, it would be essentially random, and not really much of a choice at all).

To act on a sensation. Impulse is a very rudimentary aspect of the human psyche. I want something and I take it. I wonder what something feels like and I do it. Yet, as these two statements probably have already implied, we cannot follow through with many of our impulses.

In fact, I would estimate most of our impulses go unfulfilled. We know the repercussions of acting out, the risks of ignoring consequences, and we restrain ourselves. But all this self-editing can be tiring. We yearn to express ourselves, to feel unhindered, free to do as we please. When people talk about "unwinding", they're talking about dropping all the restraint, the rules and restrictions -- of going someplace safe where they can fulfill at least a small subset of impulse; be it a den, a hike, or a video game.

Influence simply states that for an action, there will be a reaction; for a choice, there will be a result. In the case of pure impulse, this relationship is rather banal: I choose strawberry jam because it will give me greater sensory pleasure than grape.

But in the case of choice based on predicted long-term influence, influence can be profound and life changing: I chose to pursue a Computer Science degree in Los Angeles and that choice directly influenced every event in my life thereafter, from the people I met to the places I went and the things I've done.

It's also worth noting that choices not only have an effect on ourselves, they often affect others and our environment. And we typically like this. We the like feeling that our presence makes a difference. When it doesn't, our role comes into question -- sometimes even our very existence. If my actions have no impact, why am I even here?

To break this down even a little more, lets look into these different dimensions of influence:

Self. At the fundamental level, people in Western cultures feel a need to have an influence over their own fate. This is a primary expectation and carries some degree of responsibility (I am responsible for what happens to me). If I climb on the roof and fall off, I have to deal with the injuries I incur.

Environment. At the next level, people feel a need to have an influence over their environment -- to change the conditions that surround them. This is a secondary expectation, and carries a moderate degree of responsibility (I am part of an environment and my actions will impact the future resources of this space). If while climbing on the roof, I damage it, I will have to deal with the leaks when it rains.

Others. At the third level, many people like having an effect on others, to share in their autonomy. This is a tertiary expectation, and can carry a high degree of responsibility (I have an influence over what happens to other people). If I cause someone else to get on the roof, I may be responsible if they fall off and hurt themselves.

The third aspect of autonomous choice is morality. Morality implies that, for many decisions, there are universally acknowledged right and wrong options. The moral guidelines are defined by society and may not always be in agreement with the desires of the individual.

Morality becomes a choice precisely when the desires of the self and the society are not in agreement; does the individual follow personal impulse or the precepts of decency? One the one hand, personal gain; on the other, social approval.

In strong societies, the choice of morality comes couched in the threat of punishment. For the punishment-fearing individual, real moral choice may be limited to the mostly trivial cases. For example, I may make the immoral choice to turn right at a red light without stopping (a minor moral infraction), but I would probably never consider murdering someone (a major infraction).

What we are talking about are laws and laws represent just the simplest example of society's influence on individual choice. Society's influence comes in other forms, less formal rules, things like decency, chivalry, respect and politeness. Each a form of moral choice, each adherent to standards determined by society. The rules are less formal than laws and so are the punishments. If I am rude, I'm not thrown in jail, but I may find that other people are less willing to cooperate with me.

Morality becomes interesting and potentially fun when you remove the threat of punishment. Many consider this to be the true test of moral fiber -- will you defer your personal desires to those of the society, even when the society is unable to enforce its rules?

Impulse in games. By virtue of the simple fact that games have limitations, they can be said to have rules. The player can not do anything he likes inside a game; in fact, there is very little a player can do inside a game compared to the real world. Yet, people often find games more liberating than real life.

This is because while many games model reality, these models are generally accepted to be simplifications or surrealistic interpretations. They are perceived as less limiting than reality because they focus on a narrow band of interactions and, within that range of focus, key restrictions have been removed.

This is because while many games model reality, these models are generally accepted to be simplifications or surrealistic interpretations. They are perceived as less limiting than reality because they focus on a narrow band of interactions and, within that range of focus, key restrictions have been removed.

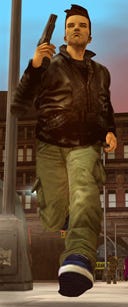

For example, in Grand Theft Auto III, I can't enroll in cooking classes, lie down on the beach, get a tattoo of a manatee or a thousand other things. But I can shoot someone with limited repercussions or steal any car I want and tool around town on the wrong side of the street until I crash and pop out, free from injury.

The thousands of things I can't do are out of the scope of the game -- as long as I don't expect to be able to do them, they aren't acknowledged as limitations. Impulse only disappoints in a game when the game sets the expectation of being able to do something, only to prevent it from being done.

For example, in a game where boxes and crates can be destroyed, finding two crates blocking a doorway that cannot be destroyed disappoints the player's impulse to find out what's through the doorway. But if the door was never there in the first place, the player would never wonder what was on the other side of the wall.

Impulse also covers the dimension of decoration. A game that allows for decoration, such as The Sims, allows players to redecorate as the whim strikes them. Blue wallpaper today, red stripes tomorrow. This sense of capricious personalization is not limited to virtual dollhouses; it frequently turns up in the form of avatar builders that let the player change or evolve their in-game appearance.

Impulsive choice is a powerful aspect of games that is becoming increasingly relevant as games are able to model the real world more and more accurately. As games become deeper and more realistic, players will be enabled to indulge a wider range of impulses without risk of consequences.

Influence in Games. Games can be thought of as systems and the player should be considered part of that system. Often, the player is represented literally, through an avatar, but other times the player acts more like a god, influencing the game world from above with no physical representation within it. In either case, it's a fundamental rule of game design that the game acknowledge the influence of the player. Influence can vary from actions causing reactions all the way to actions causing permanent reconstruction of the game world.

Persistent influence has evolved from early examples like Pac-Man, where the player gradually cleared the board of dots, to today where, in many modern shooters, the players can literally tear down the environments around them.

Modern RPGs, such as the Elder Scrolls series, strive to go even further and create "living" worlds where decisions follow the player through the game. Taken to this extreme, influence seems to be in opposition to the goal of impulse; persistence means players can't act impulsively and without consequence.

But there is a benefit to actions having lasting effects; as decisions carry greater weight, the fantasy becomes more immersive. The fictional world feels more real. Influence enables one type of fun at the expense of another.

God games take the most extreme approach, and embrace influence as more than just a source of realism: as a source of entertainment in itself. The player is no longer a simple actor who must deal with the consequences of his decisions. The player is a god, free to decide the lasting fate of others.

In games like Civilization, Black & White, or SimCity, the player has complete freedom to steer the fate of a society without fear of direct consequence. Sure, there are explicit objectives to these games, but for many, they take a secondary role to the freedom of choice and influence. As a child, I can still remember discovering I was in the minority of my peers in that I played SimCity primarily to build cities and not destroy them.

Morality in games. Up until recently, games paid very little attention to morality. Conventions like killing enemies by the thousands, invading NPCs' homes without thought and destroying furniture in the search for cash and power-ups are evidence of this legacy.

But as video games have become richer experiences and greater depth has been instilled into their worlds, they have come much closer to modeling our real world. As the resemblance gets closer, it becomes easier to project the morals of our real world onto the game world.

Many modern games have embraced this convergence, introducing simple morality or karma systems into gameplay. In these systems, certain actions increase karma, others decrease it, and the result is the player is labeled as either "good" or "evil". More often than not, the karma system is also tied to the unlocking of features, and the choice runs the risk of becoming more tactical than moral.

For a decision to be truly moral, the tactical results of the two options should be difficult to compare. For example, "evil" provides wealth, while "good" provides reputation, and translating between the two is an inexact science.

Mass Effect 2 does a good job of isolating morality in choice by building morally ambiguous scenarios and then asking the player to arbitrate. The dilemmas involve significant story investment yet carry little actual gameplay relevance (at least that the player is able to predict while making the choices).

In a different example, Modern Warfare 2 has a controversial airport massacre scene, "No Russian", where the user is asked to fire into a crowd of innocents. Whether the player chose to contribute or simply fire into the air makes no real difference to the progress of the game, but probably leaves a lasting impression in the mind of the player nonetheless.

In a different example, Modern Warfare 2 has a controversial airport massacre scene, "No Russian", where the user is asked to fire into a crowd of innocents. Whether the player chose to contribute or simply fire into the air makes no real difference to the progress of the game, but probably leaves a lasting impression in the mind of the player nonetheless.

Morality is not limited to realistic video games. A game need only evoke parallels to real-world moral choices to be effective. Brenda Brathwaite's widely cited experimental board game Train was able to pose moral tension through simple toy trains and wooden pawns.

The objective of the game was to cram as many pawns into your boxcar as possible and move it to the end of the track. The moral difficulties arose from the aesthetic elements, which not-so-subtly invited players to imagine themselves as German officers tasked with transporting people to concentration camps.

Because morals are inherently personal, it's advisable to approach them objectively. Rather than force subjective "good" and "evil" labels on players, provide opportunities to draw parallels to real-world moral dilemmas (for example to sacrifice an individual for the good of many) and then give your players the freedom to choose without persuasion. If the moral choice is too clearly one-sided, tactical incentives could be added to "balance" the choice and encourage players to weigh morals as part of a larger equation.

Individuals are daily faced with conflicting demands. Selfish demands to acquire resources and leave a lasting legacy and moral demands to respect others. This balancing act of constant compromise rarely gives individuals the opportunity to indulge either side to satisfaction. Games offer a virtual environment where players have the opportunity to play with power, influence and responsibility in a context where they have the freedom to explore choices reality does not afford.

For this vicarious experience to be effective, the game environment must be able to accurately model the real-world choices. In non-games, where modeling an entire world is probably not feasible, the focus will most likely need to be narrow and explicitly designed.

We're all familiar with the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat. Not only is it a familiar phrase but, unless you've grown up with the world's most protective parents, you've probably experienced both ends of the spectrum a few times yourself.

Literally, competition describes a situation involving two or more parties, the outcome of which results in a winner and a loser. And as the initial quote implies, competitions tend to be emotional, so much so that you might be inclined to ask why competition wasn't included back in the emotion section. There's certainly ample reason to address it there; I've personally seen grown adults do some very emotional and inappropriate things for no reason other than competition.

Yet I think there is a distinction that makes it wise to address competition separately. Without competition, the emotions of games are largely vicarious: the player feels empathy for a protagonist. With competition, the protagonist is the self and the empathy is direct.

In a way, competition is a vehicle for emotion (particularly drama). Once competition enters the picture, many people can't seem to emotionally separate reality and fiction; we project ourselves into the game so completely that there is no longer an emotional distance between participant and game.

And this is what makes competition so powerful. Competition is raw emotion. Anticipation, Anxiety, Fear, and Elation all come bursting out uncontrolled, an emotional rollercoaster that is as exciting as it is unpredictable.

Anything that can be measured can be competitive but once one gets down to categorizing, competition seems to fit into seven broad dimensions:

Physical skill. Competitions of strength, speed and accuracy. Includes sports like baseball or surfing, and reaction-based video games like Pong or Call of Duty.

Physical skill. Competitions of strength, speed and accuracy. Includes sports like baseball or surfing, and reaction-based video games like Pong or Call of Duty.

Creative skill. Competitions of creativity, such as painting, dancing, cooking, directing, writing, etc. The goal is to innovate and please the sensibilities of a group of judges.

Mental tactics. A broad category that includes anything strategic -- that involves reading and predicting the behaviors of a system (including the influences of other players), from Civilization to chess to the play-calling of American football.

Diplomacy. A form of strategy that involves reading and predicting the behaviors of potential allies and acting with the intent of influencing opinions. Often called politics, or popularity, and includes contests from elections to hierarchies to multi-sided war games.

Knowledge. The accumulation and mastery of rules or facts, from highly formalized games like bridge, to straightforward trivia contests. Can also act as an alternate approach to mental tactics -- if the rules of a system can not be deduced, optimal strategies can be observed and memorized.

Time. Competitions of persistence or patience, measured by time and participation. Includes contests of participation such as a radio show call-in, an online social "mafia" game, or a staring contest.

Luck. Anything truly random, including (in many aspects) dice games, card games, sports, gambling, etc. Yet, given structured analysis, statistical odds become predictable and, over multiple trials, luck games will evolve into contests of statistical knowledge.

In many cases, a competition takes the form of some combination of the above seven forms. For example, the game show Wheel of Fortune requires both knowledge and luck, while a Madden football game requires physical skill, mental tactics and knowledge of the opposing team, and StarCraft involves at least a little bit of almost all of the categories (the exception being creativity).

In a true competition, success is measured relative to the performance of the other players. This means that if one player succeeds, another necessarily fails (the metaphorical sum total of their success being zero).

A competition in which everybody wins is not a zero-sum competition. Although if one player is recognized as winning more than the others, the competition could be perceived as being zero-sum (in this case, the performance of the theoretical average player would count as zero). A college course that grades on a strict curve is an example of a zero-sum competition.

The distribution of winners and losers does not need to be symmetrical across the full set of participants to count as zero-sum. For example, in Monopoly, only one player wins while all the others lose, and in credit card roulette, only one player loses while all the others win.

In some competitive environments, the zero-sum comparison may not be explicitly measurable by the community at large. For example, imagine a community of players ranked according to performance. Participants are only shown a leaderboard of the top 10 players. In a large community, where the bottom end of the range is essentially unknown, many ranks lack context. (Is 4,557 a good rank?)

Yet it's naïve to assume that just because the zero-sum is not clearly expressed, it doesn't exist. Players will fill in the blanks by estimating their success, and often not accurately. Imagine in this community there is only one measure of success: being on the leaderboard or off the leaderboard. If the actual size of the community is 10,000 players and only 10 players appear on the leaderboard, there is a strong implication to 9990 of the players that they are losers.

The takeaway is players have a tendency to seek out the zero-sum, whether you make it explicit or not.

A competition which is not zero-sum is not truly a competition against other players but actually a competition against a system. Although players' progress may be compared, they are measured against universal thresholds and not relatively.

An example is a college course that does not grade on a curve. The advantage of non zero-sum is that it does not require losers. A possible disadvantage is that some of the thrill might be removed from winning if it is possible for everyone to win.

Not all competitions are "fair" -- meaning not all competitors start the competition with an equal opportunity to win. But games, as a form of entertainment, almost always strive to be fair, meaning all players start with a roughly equal opportunity of victory. The only unfairness in games should be the player's innate natural ability (i.e. physical skill, mental talent, etc).

An alternate means of breaking fairness that has been turning up lately, is buying an advantage. While this can be profitable for the game's maker, it is potentially dangerous to the integrity of the game if it weakens the significance of the other forms of competition (tactics, skill, etc).

The profitability of most social games is based on buying advantages. In most cases, money seems to be most acceptable as a replacement for time and this may not be unusual; in a world of hourly wages, we are already conditioned to perceive time and money as analogous.

Almost everybody likes to win and very few enjoy losing. The very reason that competition is so appealing -- the thrill of victory -- creates an equal opportunity for being unappealing -- the shame of defeat.

Some social games have managed to create the illusion of a zero-sum situation in what is actually an "everyone wins" situation. Bluntly, this means hiding failures by "paying off" defeats from the game system itself. For example, if this technique was used in Monopoly, the bank would help players by paying the majority of their debt every time they landed on a rival's property.

One consequence of this technique is an inflating game economy, another is a game that will never end (the latter being desirable in a social game).

Probably more than any other topic covered in this series, competition is the aspect of fun most strongly associated with games. If there is one thing competition does to a non-game activity, it's make it feel like a game.

It's also incredibly easy to accomplish -- simply measuring a behavior and comparing it between participants implies a competition -- so it may be perceived as an easy gamification win. But as I mentioned at the start of this discussion, competition can be highly emotional and therefore cause stress.

It's one thing to include competition as an expected part of a game, it's entirely something else to have competition appear in a non-competitive activity, such as running errands, or donating your time.

For better or worse, competition changes the entire context of a behavior or activity and this change should not be taken lightly.

A study of the desire for autonomy:American Psychological Association

http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2011/06/buy-happiness.aspx

Brenda Brathwaite's GDC talk on Train

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like