Game Balancing: Controlling the Spread

Another vital consideration when designing and balancing a system is what I call the Spread. The spread represents the overall difference in capability between the BASE value of a mechanic and the UPGRADED or FINAL value of the mechanic.

Another vital consideration when designing and balancing a system is what I call the Spread.

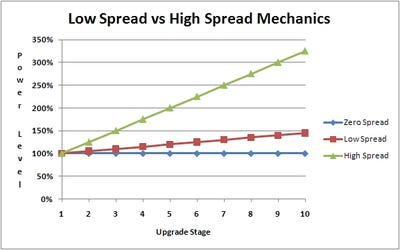

Comparison of High and Low Spread Mechanics

The Spread represents the overall difference in capability between the BASE value of a mechanic and the UPGRADED or FINAL value of the mechanic. Yeah, that doesn't make a lot of sense yet, so here are my working definitions:

MECHANIC: this could be any function in the game. For example, Shooting Accuracy, Weapon Damage, Knight Production Rate, Mana Recharge Rate.

BASE VALUE: the value that respresents the lowest level of that mechanic in the game. This might be Melee Accuracy @ level 1, Pistol Damage with a completely unupgraded weapon, or Wall Defense Multiplier for the lowliest wall.

FINAL VALUE: the value that represents the other (highest capability) end of the spectrum for that mechanic. If max character level is 20, then it would be Melee Accuracy @ level 20. Pistol Damage with a max-upgraded pistol. Wall Defense multiplier for the most advanced city wall you can build.

SPREAD: the difference between the FINAL VALUE and the BASE VALUE.

The size of the spread has many implications on gameplay and game balance.

SMALL SPREAD:

Easier to balance

Less chance of a broken game

Players *may* feel less rewarded upon upgrading

LARGE SPREAD:

Harder to balance

More risk of game-breaking

Players are more likely to notice upgrades and feel rewarded

Those are pretty obvious, but worth listing because their obviousness is what makes them useful. A bit more discussion is in order, however:

EASE OF BALANCING

Imagine a mechanic that has the same BASE and FINAL values. In other words, spread is 0. In this case, your only challenge in balancing is to tune this single value. Make so the pistol does about the damage you want, and you're done. Since progression is flatlined, your job is easy! (or easier, anyway)

Now imagine that the spread is huge. A rusty glock does 1 pt of damage, but a Super Upgraded Future Glock does 1000 pts of damage. Balancing the weapon power versus monster hitpoints (e.g. the progression curve) will be more difficult than the zero-spread design.

BROKEN GAMES

In this case, by "broken" I mean a difficulty curve that is way out of whack with the player capability curve. The game will either be terribly dull or impossibly hard, at the extremes. If the game is multiplayer vs., then "broken" could mean that player balance is way-off.

Either way, zero-spread mechanics will only break your game if you are horribly negligent (aka incompetent balancer). But high spread mechanics can elude control of even skilled systems designers, depending on what else is going on (other interacting mechanics, for example).

PLAYER REWARD

High-spread mechanics can give the player great senses of accomplishment. "Wow, before it took 5 shots to kill each bandit, but now I can drop one with every shot. I'm great!"

Low-spread mechanics have the *risk* of not providing this same satisfaction. I say "risk", because even low-spread mechanics CAN give the player great senses of progression...but it has to be handled carefully. Often, communicating the reward to the player is more about level ups, dialogue, presentation, etc., and less about actual in-game power.

For example, if you have saved up for two levels to buy the "MIGHTY BLOW" damage power which adds +20% to damage, your reward might be most perceptible as the actual purchase of the ability, rather than its effects. In other words, +20% damage isn't enough to lay waste to entire orc villages if you weren't already capable of it. It's an incremental upgrade. But if the way the skill purchase is handled is done with flair, it can still feel like a major upgrade--especially if the whole game systems are designed around incremental upgrades of +5%, +10%, etc.

WHAT DOES ALL THIS MEAN?

First, let me say emphatically that I am not counseling to always design a low-spread system!

But generally, the higher spreads you adopt, the more risk of unabalance you accept. If you have excellent playtesting systems and metrics in place, then that's ideal. If not, you might want to think about restraining upgrade spreads in order to minimize balancing challenge.

As an interesting note, if the game systems are all about small/incremental upgrades and that means overall low spread, those upgrades can still be EXTREMELY valuable to the players.

Imagine a competitive game (e.g. Starcraft) where skilled players regularly face comparably skilled players. An upgrade of 10% could end up being the difference in the match outcome.

PRACTICAL EXAMPLES

In Age of Empires: the Age of Kings DS, I consciously designed the technology tree to be somewhat low-spread. While the overall aging-up system was high spread (large differences in capability between Age I units and Age IV units), the individual upgrades in unit capability, economy efficiency, etc. are incremental--5% here, 10% there. This was done for all the reasons listed above--high spread upgrades would dangerously add instability to the game, and I knew we were short on playtesting resources. Keeping the incremental upgrades small helped put some fences up to keep balance in, but the upgrades were still worth pursuing for the player (especially because one requirement of "aging up" was a certain amount of techs researched, regardless of what those upgrades were--so the typical "break-even" anaylsis for tech research was trumped by overall need to research. That is, players had a reason to research even aside from what the actual upgrades were.)

I see elements of low-spread design in Mass Effect 2. Most of the individual upgrades are in +10% increments or below. E.g. +10% Pistol Damage, or +6% Power Duration. If you get all 5 Pistol Damage upgrades, your pistol does +50% more damage. It appears the enemy difficulties are dynamically scaled as well (?similar to Oblivion?), so the net effect is to reduce the overall player spread balancing difficulty. In other words, gaffes in balancing can be partially mitigated by the dynamic enemy scaling. Notice that Mass 2 never shows you actual weapon metrics, either? You know you have upgraded your weapon, but you don't know actual brass tacks damage. A large portion of the upgrade player reward is simply knowing you earned it. After you've probed a sh*tload of planets, it feels good to purchase that SNIPER RIFLE DAMAGE UPGRADE.

One example of a high-spread mechanic is HP in classic AD&D. A first level figher could have 10-ish HP, but a 12th level figher might have 120 HP. That's a huge range, but one that was deemed core to the game's mechanics. It certainly provided a large-scaling sense of power progression. Balancing-wise it could be tricky, but HP was basically the central mechanic in the game, so monster and encounter design was all based around it and rules of thumb could be codified through experience.

OOPS

I just used the word "codify", which is always a signal to me to stop blabbing. Thanks for reading!

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)