Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Former Sony Computer Entertainment artist Chris Solarski takes us on a tour of art from classical to modern, and in the process shows how film and game art are underpinned by foundational concepts.

[Former Sony Computer Entertainment artist Chris Solarski takes us on a tour of art from classical to modern, and in the process shows how film and game art are underpinned by foundational concepts.]

The notion that artistic ability is a divine gift has proliferated throughout history -- it's an idea often propagated by artists themselves. However, Michelangelo, the Renaissance genius did, in fact, experience the odd lousy day of drawing just like the rest of us. He burned many of his sketches to conceal the intense work and discipline that was vital to the creation of his masterpieces.

"If people only knew how hard I work to gain my mastery, it wouldn't seem so wonderful at all."

This point is not intended to dismiss Michelangelo's abilities, but rather highlights that a successful artwork doesn't generally just happen. Art that has a lasting appeal is predominantly the combined outcome of three elements: training, discipline, and natural ability.

Artists today have over 2000 years worth of artistic principles to draw from, including principles on form and composition to developments in color theory and light.

What these principles constitute is our visual vocabulary. Artists can play with the viewer's eye like never before to not only create believable other-worlds, but to also manipulate how viewers will receive these worlds in terms of emotional significance.

Despite the empowerment these principles give us to communicate visually, the theoretical aspect of art has been somewhat sidelined in the last century. With the arrival of modern art it is often no longer a case of artists concealing their hard work and knowledge of artistic principles, as with Michelangelo's sketches, but ignoring these principles altogether.

Whilst overemphasis on theory can indeed inhibit creativity, in the field of video game development we are especially interested in taking advantage of traditional artistic principles to enhance the player experience. This is because our task is to design a player experience, meaning a deliberate attempt to influence an emotional change in somebody. It is not simply any emotional change.

Surprisingly modern art, a period that has actively sought to sever itself from tradition, has contributed many new devices to our visual vocabulary that naturally build on what came before. At the same time, this very same movement has had a negative impact on the education system. What does this mean for the video game development industry and video game artists?

To investigate these questions we must journey back to the beginning of Western art before evaluating the impact that tradition can have on contemporary design. By doing so we also examine whether arts evolution is a continuous thread of development or a series of isolated artistic movements.

Our journey starts in ancient Greece and focuses on a principle often missing from applied art courses; something that influenced subsequent generations of artists such as Michelangelo: applied geometric forms. No divine blessing required, although that always helps.

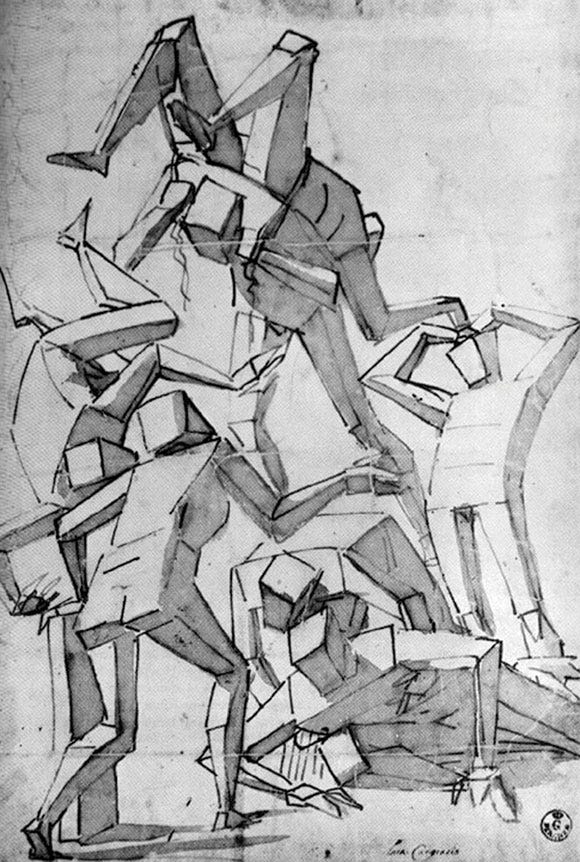

The ancient Greeks laid a miraculous groundwork for Western culture, and these early philosophers equally affected the arts. One such artistic principle that was established over 2,000 years ago was the process of simplifying complex forms. Believing that everything in nature aspires to the perfection of geometric forms such as the sphere and cube, old masters would use these primary forms as foundations for their masterpieces. An artist whose preparatory sketches explicitly illustrate this principle is Luca Cambiaso.

Preparatory study by Luca Cambiaso demonstrating the process of simplifying the complex human form (16th Century)

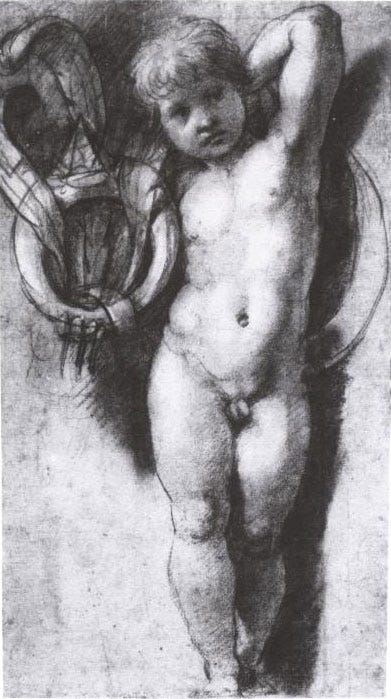

The chalk study by Raphael -- the high-mark of classicism in the Renaissance[i] -- shows us how the concept of simplification appears in a drawing developed to a higher degree of finish. Of primary interest is how these artists reduced the forms of the body -- the ribcage, pelvis, and head being the largest and most important [ii] [iii] -- to box forms and large simple shapes.

Putto carrying the Medici ring and feathers by Raphael Sanzio (1483-1520), Teyler Museum, Haarlem.

What is significant about this principle not only relates to the practical benefits for the artist: the box's simple planes and eight corners make it easier to render an object's three dimensional form and orientation in space without the distraction of details. It is also significant for the fact that a simple concept makes it is easier for viewers to comprehend an artist's message. In other words, less is more.

This classical approach to drawing is very much based on principles originating from a period when art was associated with craft rather than individual expression, as it is now. Artists of the Renaissance would have spent upwards of 10 years perfecting their skills under the guidance of a master. As late as 1860 in the time of Jean Auguste Ingres, mastery in drawing was considered a prerequisite to painting. For about six hours each day, students drew from a model, who remained in the same pose for one week.[iv]

Attitudes towards art and long-held traditions started to change around the start of the 19th Century. Artistic expression split from craft in reaction to liberating cultural changes, which led to the general movement known as modern art. Correspondingly, the established education system championed by traditionalists like Ingres also began to change. These events did not transition smoothly with general consensus. As it turns out, the art world is not one big happy family.

[i] Vilppu, Glenn. Language of Drawing Series, Vol.6: The Classical Approach to Figure Drawing. Vilppu LLC, 1985.

[ii] Bammes, Gottfried. Die Gestalt des Menschen. E. A. Seeman, 1964.

[iii] Bridgman, George B. Bridgman's Life Drawing. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1971.

[iv] Boime, Albert. Strictly Academic: Life Drawing in the Nineteenth Century. SUNY at Binghamton, 1974, p8.

A conflict between tradition and modern art is evident in the words of one artist who helped bring about the latter movement, Henri Mattisse, who in 1925 exclaimed frustration at his students: "Many of my students were disappointed to see that a master with a reputation for being revolutionary could have repeated the words of Courbet to them: 'I have simply wished to assert the reasoned and independent feeling of my own individuality within a total knowledge of tradition...' The saddest part was that they could not conceive that I was depressed to see them 'doing Matisse.'" [v]

Contrasting paintings by two masters of their time illustrates the changes in art culture within the space of 100 years: The Valpinçon Bather (1806) by Jean Auguste Ingres, Paris Louvre, with The Dance (1909) by Henri Matisse, New York's Museum of modern art.

I discussed this conflict of traditional principles in contemporary education with graduates from renowned British institutes such as the Royal Academy of Art and Wimbledon College of Art.

One student described their Communication Art & Design BA as having a strong emphasis on "doing your own thing". A graduate of Fine Art Painting said that the teaching of traditional principles, including the practice of life drawing featured in the first semester, felt like a relic of an older system.

"You'd think that the course could accommodate various styles. Instead, you're taught a trend," proclaimed the graduate of Painting.

The situation seems very dire for organizations such as the Art Renewal Center (ARC), which endorses a meager 60, or so, art academies around the world for their "genuine art instruction."[vi]

With widespread privation of education -- in the UK at least -- universities are forced to cater to popular demand. This means that education leans more towards conceptual forms of art, such as abstraction and expression, as opposed to traditional practice. The dilemma is that even teachers are often not in a position to give comprehensive tuition on traditional art principles, having gone through the very same education system.

As a result, a graduate of art history will likely have a stronger understanding of traditional principles than somebody with a background in applied arts. By and large graduates of applied art courses are simply unaware of what they're missing out on.

Game design courses focusing on art are even more confounded by the fact that they also feature technical elements in the curriculum, leaving students with even less time dedicated to traditional art principles and more time working at the computer. Although some technical knowledge is indeed important, to what extent should art students be taught about programming, considering that the majority will eventually specialize in either a technical or artistic discipline? The education system is clearly not meeting everybody's expectations (although it arguably never does!).

The conflict between traditional and modern schools escalated in 2004 over David Hockney's controversial book, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters.[vii] ARC, being a vehement campaigner for tradition, was outraged by Hockney's misguided attempts to demystify the accomplishments of "realism" in classical painting, with articles featuring terms as severe as "aesthetic genocide." [viii]

Hockney's theory stems from the author's self-confessed incomprehension of how old masters could have created such realistic paintings. As artist Kirk Richards points out, there are many contemporary artists who can openly demonstrate their ability to paint realistically from life.[ix] It appears that Hockney's conclusions are based on the sad fact that he's completely oblivious to the artistic principles which the old masters exercised.

The surrounding controversy illustrates ignorance by both traditional and modern schools. What both parties overlook is that modern art movements such as Abstraction and Expressionism have given artists new visual tools with which to communicate; that modern art doesn't constitute a complete break with tradition but offers an evolution instead.

Before the discussion of Hockney's Secret Knowledge, our thread stopped mid-19th Century with Jean Auguste Ingres, a veritable guardian of artistic tradition. By the time we come to Impressionism around 1900 -- a key turning-point towards modern art in the 20th Century -- tradition is seemingly on its way out.

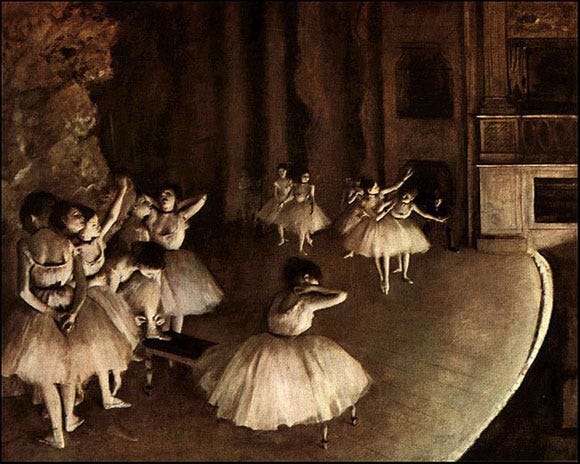

On the surface it's easy to assume that much of modern art is an outcome of pure expression however there are many links with tradition that we can investigate. We will focus on one particular artist, given the limited scope of this text, who was highly progressive yet valued tradition and the old masters. His name was Edgar Degas.

Whilst Degas idolised Ingres' classical style, he was among the first artists "to see what photography could teach the painter and what the painter must be careful not to learn from it," wrote the French writer, Paul Valéry.

Although Degas is best known for his ballet paintings, it is less known that he copied from photographs, being an accomplished photographer himself. By the 1890's, Degas owned his own camera and developed "characteristic compositional and lighting techniques." [x]

"Visitors to Degas's studio recalled how the master draftsman pinned sheets of tracing paper to cardboard, adding strips of paper as needed to complete his compositions. Here, the female figure, which he may have traced from another picture, occupies the largest sheet of tracing paper, with three separate sheets -- to the left, right, and on top -- extending the format." [xi]

From a traditional drawings and observations from life, Edgar Degas would experiment with compositions using a method akin to Photoshop layers. His finished works share more in common with the modern school of tonal painting, inspired by photography (circa 1875).

What is described here is, in essence, the precursor to Photoshop. Degas cut, copied, flipped, scaled, rotated and combined images with the aid of transparent tracing paper. Such techniques along with Impressionism's emphasis on tonal painting and color, paved the way for a new form of visual communication in the form of increasingly abstracted images. Abstract shapes began to have emotional significance, eventually becoming icons in their own right.

An example of a visual conversation with primary shapes in Wassily Kandinsky's Bauhaus oil painting using circles, squares and triangles (1965).

Iconography isn't just the realm of the Abstract Movement and artists like Wassily Kandinsky. Principles concerning the emotional significance of shapes are regularly incorporated into all art and design disciplines however they're so culturally ingrained that they generally go unnoticed. So where else do we find them? Let's start by looking under our very noses; within the media we consume daily and film.

[v] Mattise, Henri. Mattise on Art. University of California Press 1925, p81.

[vi] http://www.artrenewal.org/pages/ateliers.php

[vii] Hockney, David. Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters. Thames & Hudson Publishers, 2006.

[viii] http://www.artrenewal.org/articles/2004/Massey/hockney1.php

[ix] Richards, Kirk. Knowledge without Substance. Review of David Hockney's 'Secret Knowledge'. Classical Realism Journal: the American Society of Classical Realism, 2006.

[x] Scharf, A. Art and photography. New York: Penguin Books, 1986.

[xi] Art Institute of Chicago: Classroom Resource: http://www.artic.edu/artexplorer/search.php?tab=2&resource=418

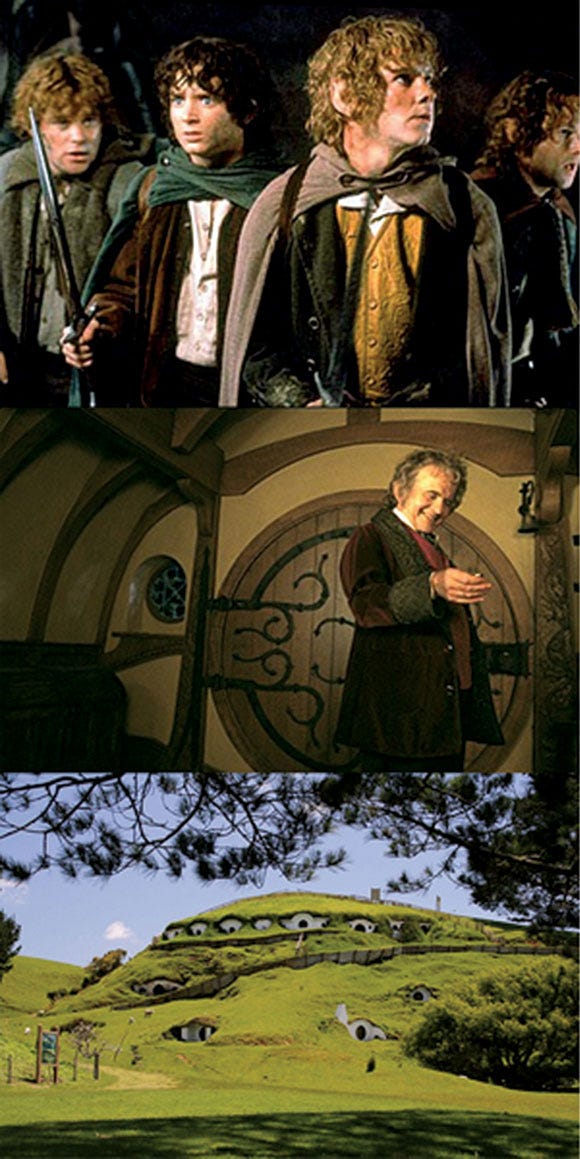

To investigate the iconography of shapes in modern media we're better off looking towards the film industry where we find one of the purest examples in The Lord of the Rings Trilogy.

Circular forms associated with the Hobbits and Hobbiton from the Lord of the Rings Trilogy (2001-2003), courtesy of New Line Cinema

At one extreme, there are the gentle, good-natured Hobbits represented by the circle. This primary shape is echoed throughout their design: in the details of their clothes, their rounded silhouettes and even the curl of their hair.

The circular concept also extends to the houses and landscape of Hobbiton. At every level of detail we find a repetition of this primary shape notably complemented by an appropriate use of earthy colors.

At the other end of the emotional spectrum we have evil Sauron whose primary shape is the triangle with its sharp point. The triangular concept is visible throughout his design and that of Mordor: from the volcano on the landscape, down to the spikes on his glove.

Here, too, suitable colours have been chosen to heighten his character.

Triangular forms associated with Sauron and Mordor from the Lord of the Rings Trilogy (2001-2003), courtesy of New Line Cinema

What we see here is that primary shapes are being interpreted on an emotional scale. The circle represents positive or dynamic energy whilst the sharp triangle is in polar opposition, representing negative or aggressive emotions.

Interestingly it wasn't a conscious decision to represent these characters iconographically, rather the designs evolved more naturally from common cultural references and Tolkien's original text.

Primary shapes in Pixar's Up; starting with the circle associated with Ellie to the increasingly angular forms of Edward, Charles Muntz and Alpha (2009), courtesy of Walt Disney Pictures.

Another great reference for the application of primary shapes is Pixar. With this film we can add a third shape to our iconographic scale of emotions: the square, as seen in the design of Edward. Traditionally straight lines symbolized strength and stability, so our square fits between the circle and triangle in the proposed scale of emotions. It's interesting to note that these traditional associations of stability have been reinterpreted slightly to also encompass an element of stubbornness in Edward's character.

Iconography of primary shapes is pervasive in all visually fields, as demonstrated here in automotive design.

Thanks to modern art such emerging principles have increased the breadth and complexity of our visual vocabulary. However the underlying philosophy originating with the Greeks remains: less is more. In this respect, primary shapes -- the circle, square and triangle -- are the simplest shapes with which to communicate emotions visually. Practically, they help artists see the complex world in simpler terms.

Primary shapes are more difficult to spot in a human face however an artist will more easily recognize them through methods of abstraction used to simplify complex forms. Me, Myself and Irene (2000), courtesy of 20th Century Fox.

From these examples it's easier to see that art is not as fragmented as the diverse amount of styles and artistic disciplines would lead us to believe. Even films such as LOTR and the abstract paintings of Kandinsky share common principles. Video games are no different, per se. Whilst character and environment designs will inadvertently share the same visual vocabulary as other media, we have the added element of interactivity to contend with. So what are the unique considerations for video game artists?

From personal experience, knowledge of traditional artistic principles isn't very strong amongst the majority of video game developers. It's not that video games have different visual needs, because we all communicate using the same visual vocabulary. The reason for this absence is partly the fault of the education system, as discussed earlier, and partly due to the fact that it's easy to be lazy as artists when visual communication is complemented by a complete multimedia experience of animated, audio, and visual prompts. However, more detail, more sound and more special effects don't necessarily lead to better communication.

Screenshot and overlay from Halo 3 (2007), courtesy of Bungie Studios and IGN.com. The overlay illustrates reduced player perception of visual detail during gameplay. Click for larger version.

With all that happens on-screen in a typical video game -- 360 degree movement, a constantly shifting viewpoint, dynamic user-interface, etc. -- players don't have time to take in all the detail which you can see in this screen from Bungie's Halo 3.

What happens is that player perception of visual detail is extremely reduced to something closer to the accompanying illustration.

As a result, it's even more essential that video game developers communicate in simpler and more direct visual terms.

Simple iconographic concepts do just that by helping players to understand their gaming environment that much quicker and differentiate, say, enemy characters from allies.

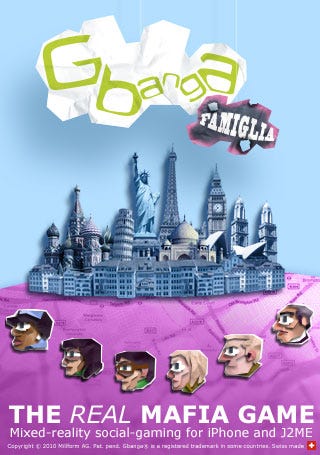

Selection of Mafia characters from the location-based, mixed-reality game, Gbanga Famiglia (2010) courtesy of Millform AG.

I face similar artistic challenges at Gbanga, which is the Swiss developer of a location-based gaming platform. Working to mobile platform constraints and supporting screen resolutions as small as 176 x 220 pixels, the emotional significance for each character must be entirely communicated in the edges and larger abstract shapes when each is no larger than 54 pixels squared. Small details are simply not visible at these resolutions in much the same way that a character in a 3D environment will appear when viewed at a distance.

![]()

Various iconic video game characters from around the world demonstrating the application of primary shapes.

Similar concepts can be observed with this ad-hoc selection of iconic video game characters from around the world. From the predominantly rounded features of Mario, to the triangular elements of his archenemy, Bowser, there appears to be a commonality in terms of which primary shapes are used for certain categories of characters. Sonic the Hedgehog's characters appear to be the only exception to this principle, which causes some semantic confusion. How conscious video game artists are of this and other artistic principles is still open to investigation, keeping in mind that the above selection of characters represents a minority group of successful titles. However the benefits of having a command over artistic principles is easy to appreciate.

![]()

The iconographic scale of emotions from passive to aggressive consisting of the circle (dynamic, positive emotions), square (strength, stability) and triangle (negative, aggressive emotions).

There may be some reluctance from artists to engage with traditional artistic principles considering the contemporary climate brought about by modern art. The conflict between freedom of expression and discipline is a constant debate as over-theorizing can indeed inhibit creativity. A quote from Juliette Aristides supports this belief that, "Often the most unique, compelling work comes not from a concept or an idea but from a deep, wordless place inside the artist." [xii]

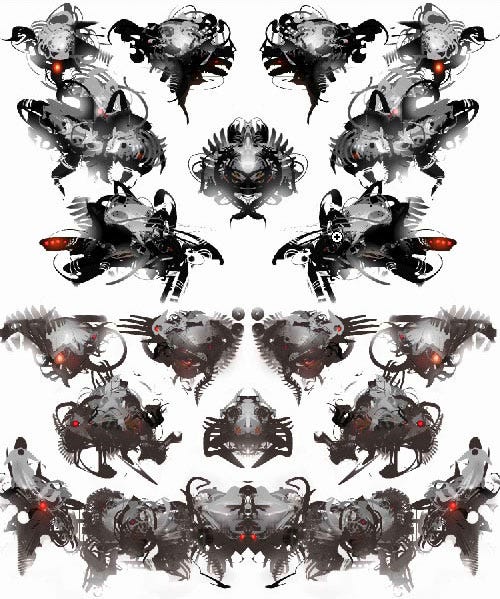

There are many artistic methods to counter the expressive restraints of theory once the latter has been learnt to a comprehensive level. A common method artists employ is to let their subconscious find images in random shapes, which is an experience known as apophenia.[xiii] Great examples of this are found in the inspirational demos of Retro Studios' lead concept artist, Andrew Jones, in which he plunges headlong into visual "chaos" using semi-automated tools like ZBrush and Alchemy to spark his imagination with unexpected ideas and images. [xiv]

Andrew Jones creates abstract images such as these to inspire his subconscious with unexpected ideas. His traditional training allows him to easily realize any idea.

What remains evident throughout Andrew Jones' demos is that he has a very strong command of traditional artistic principles, allowing him to easily realize an idea once inspired. The same holds true for Degas, Ingres, and Michelangelo; artists throughout history have always held traditional principles in the highest esteem because they form the basis of our visual vocabulary. Their significance is timeless.

What these artists also valued was the practice of drawing from a life model, which develops in the artist a discipline for simplification, as there is no other way to successfully capture a dynamic and highly complex subject such as a human being when armed with just a pencil and paper. The act of drawing also makes the relationship with a subject more vivid than when using secondary reference. Consider the difference between witnessing something as spectacular as a whale swimming in the ocean, with watching a televised documentary about one. Firsthand experience wins hands down.

The ideal trajectory of an artist's path to learning and experience is best summarized by a quote from the master Japanese painter and printmaker, Katsushika Hokusai:

"At seventy-three, I learned a little about the real structure of animals, plants, birds, fishes and insects. Consequently when I am eighty I'll have made more progress. At ninety I'll have penetrated the mystery of things. At a hundred I shall have reached something marvelous, but when I am a hundred and ten everything I do, the smallest dot, will be alive."

Aristides, Juliette. Classical Painting Atelier: A Contemporary Guide to Traditional Studio Practice. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 2008.

Carlson, John F. Carlson's Guide to Landscape Painting. Peter Smith Publishing Inc., 1984.

Glenn Vilppu's educational DVDs, http://www.vilppustore.com/

Hale, Robert Beverly. Masterclass in Figure Drawing. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1991.

Mattesi, Mike. Force: Dynamic Life Drawing for Animators. Focal Press, 2006.

Quiller, Stephen. Color Choices: Making Color Sense Out of Color Theory. Watson-Guptill, 2002.

Schmid, Richard. Alla Prima: Everything I Know About Painting. Stove Prairie Press, 1999.

Ruskin, John. Elements of Drawing. Dover Publications Inc., 1857.

The Society of Figurative Arts Forums, http://www.tsofa.com/forums/

[xii] Aristides, Juliette. Classical Drawing Atelier: A Contemporary Guide to Traditional Studio Practice. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 2006, p97.

[xiii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apophenia

[xiv] http://androidjones.net & http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lybxxbpjjnw

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like