Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Free-to-Play is A-OK

What does free-to-play mean for game design? Is it a new frontier or a vile, corrupting force? Is it possible to have a conversation about it, or should we just write it off as intrinsically evil?

[This is a repost from the official Robot Invader blog. You can find the original article here. --CP]

Let's talk about free-to-play games.

I mean, really talk about them. Pick them apart. Analyze them. Maybe even learn a few things.

Because sometimes I feel like talking to game developers about the topic of free-to-play games is like talking to a brick wall. "I don't play free-to-play games," one developer, who's work I really respect, told me smugly when he learned that our games cost nothing to try. His game, an XBLA title, costs nothing to try either.

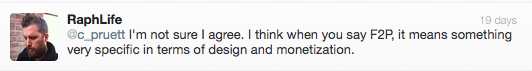

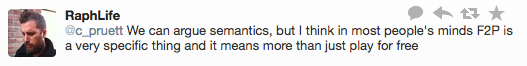

I don't think we even agree on what "free-to-play" means. I think it means "a game that you can play for free that also has things you can choose to buy in it." But when I floated that definition on Twitter, a number of people disagreed.

(thanks to Teut and Raph for humoring me on this point.)

I've noticed that developers tend to get themselves worked up over a specific free-to-play implementation and then, rather than take that particular design to task, turn around and blast all "free-to-play" games. You hate Farmville because you see it as a Skinner box thinly disguised as a game, created for the express purpose of extracting money from its player's wallets. Fine. But what does Farmville have to do with Temple Run 2? Or Real Racing 3? Or The Walking Dead? These are all free games with in-app purchases built into them, but they have very little in common. Too often the conversation ends before it starts with arrogant platitudes like "I don't play free-to-play games."

Welcome to the Dark Side

Thankfully some developers are willing to dive deeper. Charles Randall's post on this subject is incisive because he captures the essence of what bothers many game developers about free-to-play games.

Charles manages to side-step a big red herring: the mechanics commonly used in free-to-play games. It's not energy systems or grinding or unlocking content or wizard hats or consumables or in-game currency that bothers him. After all, every one of those mechanics can be found in traditional paid games, and thus can be justified absent monetization.

Rather, it's the idea that a game that asks for purchases in the midst of play just might be designed to manipulate you into paying. Charles sums up this general uncomfortableness well:

Beyond these issues, there are the questions that F2P games raise in my mind while I play. How can I know that I am not being manipulated? If I am playing the game, but it gets grindy, and there are purchases which will alleviate the grind, what were the reasons for the grind in the first place? Did the designer believe that the grind was the optimal path for the game to be engaging, or was the designer making conscious decisions based on conversion metrics?

The problem, according to this point of view, is that even if a particular game element (say, grinding) has real game design utility, the very existence of in-app purchases causes players like Charles to wonder if the element was inserted just to make money. The design has been tainted, or "corrupted," as Charles would say, by the need to monetize. This is, I think, a very common view amongst traditional developers.

I also think it's a pretty weak argument, for several reasons.

First, the basic premise of the "f2p corrupts game design" argument is that paid games are different. It assumes that traditional games do not include elements that have no purpose other than increasing the developer's bottom line. This is, of course, completely false. Why do so many console games feature women in skimpy armor? Why would a developer ever bother making a game featuring somebody else's intellectual property? Why does Alan Wake have ads for Verizon, why does Peter Parker's camera say CyberShot on it, and why does the loading screen of Wipeout 2 feature the Red Bull logo? Heck, why do we need better graphics in our game devices? Developers may not think about it this way, but traditional games are designed from the ground up to be financially successful.

Game design: corrupted!

Of course, there are some games made without any concern for future profit. I'm a big fan of Tale of Tale's work, for example. But this is probably not what developers have in mind when they are thinking about the general merits of paid games compared to free games. The truth is that all commercially produced games are influenced by the need to be profitable. Whether it manifests as a character design (would God of War have been successful without Kratos?), superfluous sex appeal, reliance on a licensed character, or graphics tech to meet customer expectations, it's always there.

And because it's always there, it's better thought of as a design restriction than as a problem. If your publisher tells you that market research has shown that the your new PS4 game must include elves, gangbangers, and a nail gun, you do your best to figure out how to make the best game you can within those restrictions. And guess what, that's what goes into making a free-to-play game too. If your market research shows that paid apps on the iTunes App Store and Google Play are dead (they are, but let's debate that point in a future post), your challenge is to make the best game you can within the format that the market accepts. Your monetization scheme, much like your control scheme, is a design restriction that you must work within. That there are restrictions that relate to your bottom line is a fact of life for all game developers, regardless of platform or price tag.

Importantly, this doesn't mean that you must trade fiscal viability for quality. Many games do make that trade--I've worked on enough licensed character games to know exactly what that entails--but it's not a requirement. Many developers are able to create financially successful games that are also quite good. The fact that money must somehow be made, and that the need to make money will inevitably influence design, is nothing new. It's just one more design restriction within which a designer must operate. A mark of a good designer is one that can make a fun game given numerous restrictions.

Let's take this a step further. It's better to think of free-to-play mechanics as a design restriction because it results in a specific player behavior: strategizing. The folks playing free-to-play games are not the Pavlovian dogs we sometimes portray them as, listlessly clicking their way through CSR Racing and happily plunking down cash for the privilege of clicking faster. Playing a f2p game seriously is all about figuring out how to get as far as possible by spending as little as possible. It becomes a hardcore min/max strategy game, and figuring out the strategy is really fun. Games like The Sims boil down to a mundane operation loop within a progression arc that the player is attempting to optimize; it is figuring out the parameters of that optimization that provides most of the enjoyment. The same is true for free-to-play games: adding purchases into the mix gives the player an axis to strategize upon, and when it works it's really fun.

Of course it doesn't always work, and not all free-to-play games are fun. But the point is that the monetization aspect of these games is absolutely a participant in the greater game design balance. In fact, in my experience it's by far the most difficult part of a free-to-play game to design. The restrictions imposed by f2p are dramatic.

Winner Take All

Speaking of balance, Charles goes to some length to make his complaint specific to games that have purchases that "affect the balance of the game." That is, games that allow the player to somehow get ahead by buying stuff. I appreciate the point; Charles is actually drilling down into the things he doesn't like rather than writing everything under the f2p banner off. But his complaint hinges on a couple of assumptions that seem pretty rickety from where I sit.

She probably bought upgrades for those arms.

First, Charles notes that pay-to-progress is "corrupting" in games that feature competition between players because the competition is no longer honest. I don't disagree in principle, but this is hardly specific to free-to-play games. By that logic, performance-heavy multiplayer games like Far Cry 3 must also be a "corrupted" design because the player who can afford the fastest PC and the best network connection has the edge. It also assumes that purchases that power the player up will always result in winning, while most multiplayer games I know maintain a delicate balance between skills and stats. Not to mention the existence of intelligent match-making systems designed to pit players with similar stats against each other to maintain fun.

Second, this argument seems to have no bearing on games where the purchases are not directly related to "triumph over a player" that is playing for free. I can pay to buy a crystal in Triple Town so that I can improve my town, but no other player is affected by that action. Even in multiplayer games, there are many examples of purchases that are about convenience for the player rather than competition with another. I have a friend who regularly buys World of Warcraft gold from China because he just doesn't have much time to play and wants to go on raids as a leveled up character. This hardly ruins the game for other players.

In fact, I think we can expand upon this idea to find the fundamental disconnect in Charles' argument. At the core of this discomfort that he describes is the assumption that the goal of a game is to win. Paying to win just feels, well, like a bit of a cop-out.

The thing is, the majority of successful free-to-play games cannot be won. They are endless. Winning isn't the point. In fact, the audience for these kinds of games isn't playing to win at all. They are playing to have a good time. They are playing for enjoyment of the moment. They went to the movies instead of purchasing the Blu-ray; buying some popcorn while they're there isn't weird, doesn't mean they've been taken advantage of, and doesn't turn the theater into a casino.

I am the Audience

I think that some traditional game developers and hardcore gamers haven't figured out that there's a new audience for games yet. An audience that doesn't share their tastes and has a wholly different idea of what games are worth. An audience that the traditional game industry has repeatedly failed to reach for thirty years. An audience that likes to be able to try things out for free and then make their own judgements about whether or not potential purchases are worth it.

I also think that many traditional developers shy away from having to participate so directly in marketing. That's what a lot of free-to-play design is: marketing to try to get the player to want to spend money. In the traditional game space, marketing is always handled by somebody else, usually off at a publisher somewhere, often demonized by the team. So it's natural that traditional devs are wary of stepping into this role, especially when it effectively becomes a part of the core game design. But of course, marketing is a fundamental component of all successful games.

What most of us think about when we think of marketing.

The point isn't to paper over the offensive things that some free-to-play games do. I just don't think that free-to-play game design is intrinsically evil, or corrupting, or actually all that much different from all the other stuff that already goes on in the game industry. There are plenty of paid games that I find offensive as well, but I also know that they are not representative of their price point or platform. Packaging up a bunch of games and categorically declaring them to be the online equivalent of casinos because they can be played for free is, in mind, a gross generalization. Worse than that, it's a meme that blinds people to the actual merits--and problems--with this type of game. It's a stereotype, a way for people to stop thinking about things they are not initially comfortable with, a way to casually dismiss them with "I don't play free-to-play games."

How's this for an alternative theory: traditional game developers look at some popular f2p games and find them lacking. The graphics are bad. The game play is simplistic or almost non-existent. It's a knock-off of a better game from fifteen years ago. And then they see that some of these games are making insane profits. Inconceivable profits. And to the seasoned developer, who has excellent taste and experience in video games, the only possible explanation is trickery. The players must be getting duped. It's the only way to square the apparent popularity with apparent lack of compelling content.

But really, it's just a matter of taste. Traditional game developers who dismiss f2p are like hardcore wine connoisseurs complaining about the popularity of Trader Joe's Two Buck Chuck. By writing off the entire category these developers miss the nuance. They miss the opportunity to learn about a different kind of game design. They miss the opportunity to speak to an audience that does not care for traditional video games. Worst of all, they miss out on some great f2p games that have top notch production values because they've decided that the problem is the price point.

I have eight different consoles connected to my TV. I own (and have played to completion) hundreds of console games. But I've also spent more on free-to-play games than console games so far this year. Which box am I supposed to fit in? Am I a wine connoisseur or a two-buck-chucker? I don't even drink!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)