Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

How do moral choices interweave with game design and player expectation? In this article, Carnegie Mellon University Entertainment Technology Center graduate student Brandon Perdue examines how games like The Witcher, Mass Effect, Heavy Rain and more struggle to offer players meaningful choice.

[How do moral choices interweave with game design and player expectation? In this article, Carnegie Mellon University Entertainment Technology Center graduate student Brandon Perdue examines how games like The Witcher, Mass Effect, Heavy Rain and more struggle to offer players meaningful choice.]

As video games have become an increasingly narrative medium, it has become popular to pose moral choices to the player. The possibilities here are promising: since games allow designers to build choices that a player must make, and consequences for those choices, video games can arguably offer profound experiences in which players must consider the implications of their (virtual) actions. However, compelling moral decisions seldom survive contact with the mechanical elements of many games, resulting in a sort of "dominant moral strategy."

I am not asserting that games have never managed to contain a moral element. Video games are a narrative medium, and in the right hands can tell strong stories. There are video games out there that tell highly moral stories without involving the player in a moral choice of any kind.

It is those that do give the player moral choices, especially role playing games, which have yet to hit on an ideal solution. This article aims to address such games that present players with explicit moral choices: many games have implicit choices, not to mention other sources of morality altogether, but to tackle the entire topic would be the work of more than a single article.

The problem is not a trivial one. The idea of a moral choice often runs directly counter to the tendency of many players to make optimal moves in the game.

The model that rewards certain choices over others, or different choices in different ways, tends to functionally make the choices for the players; the player will be more successful at the game if he picks the optimal choice for his strategy.

Often, the result is that only extreme moralities -- flawless good or evil -- are substantially rewarded. Playing any sort of middle-ground is a poor decision, from a gameplay perspective. (The so-called "Han Solo problem" which titles such as Fallout 3 and Fable II have tried to overcome.)

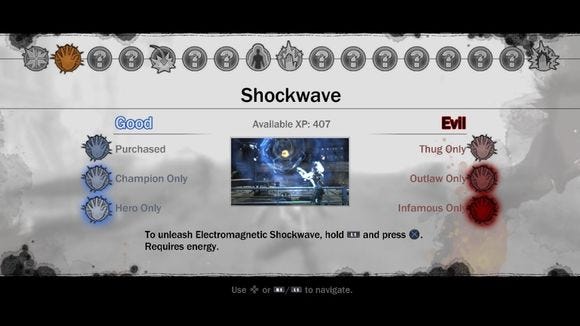

Take Sucker Punch's open world superhero title Infamous. A key feature of the game is the good/evil continuum and the various choices that affect the player's position on that continuum. At certain milestones the main character, Cole, unlocks new powers and abilities, and these differ depending on whether he is trending good or evil. The decisions do change the nature of gameplay a little, and each alignment has a set of unique missions that the other does not get. Neither direction is objectively better than the other, though one might appeal to an individual's play style more than the other.

However, if the player does not become either extremely good or extremely evil, the highest-tier powers remain locked; Cole cannot utilize a mix of good and evil abilities at once. The only choice that really matters, then, is the initial one: to build a good Cole or an evil Cole. Straying from that path later results in far more limited options, weaker gameplay, and an early end to character progression. In essence, the game punishes the player for being inconsistent.

You can only gain new abilities in Infamous based on your alignment.

It is worth contrasting Infamous with the well-known examples set by years' worth of Star Wars games that track the player's stance between the Light and Dark Side of the Force. Beginning, perhaps, from 1997's Jedi Knight: Dark Forces II and continuing in several successive titles, including Jedi Knight's direct sequels and the popular Knights of the Old Republic franchise, this approach works within the fairly polar morality of the Star Wars mythos.

Unlike Infamous, the mechanical impact is not on what powers the player can acquire, but how powerful they are; a player with a heavily Light Side tendency can still learn Dark Side Force powers, but they will be weaker than if a Dark Side character used them. The choices themselves, however, still fall along a discrete continuum, and often only contain clearly good and clearly evil options.

Removing the continuum adds a degree of freedom, but such solutions often track the player's morality and score it somehow. A prominent example of this is BioWare's Mass Effect, where the player character, Commander Shepard, has both a Paragon and Renegade score. These two categories are a little more abstract than simple good or evil; they might be described as "diplomatic" and "aggressive", respectively. But taking a Paragon action does not reduce Shepard's Renegade score and vice versa. Players accrue scores in each separately.

This might work reasonably well if not for the abilities they bestow: "Charm" options appear in conversation if Shepard's Paragon score is high enough, and likewise "Intimidate" options appear if his Renegade is high. Some situations do not require a very high score to offer these options, while others require an extremely high score. Further, these options are always visible to the player even if his score is too low to use them; he knows what he's missing out on, and whether he needs to be more good or more evil to get to it.

Charm and Intimidate options are categorically better than the standard dialogue options, but if the player splits his focus between Paragon and Renegade choices, there will be many instances when neither score is high enough for this options to be available. Once again, there is a mechanically optimal way to make these choices: saintly Shepard (or unpredictable loose cannon Shepard) will always be more successful than a more balanced character. Mass Effect has a dominant moral strategy.

There is plenty of reason to try to quantify a player's moral choices somehow in the game system. It allows rewards for certain kinds of activity. Non-player characters can react according to a player's reputation. Certainly this can be tracked "under the hood", and has been in some games, but there is a level of satisfaction -- not to mention indirect control -- in giving the player a clear measure of their moral standing.

But if whether or not to include and act on this measure were the only hurdle in giving players compelling moral choices, this would be a relatively simple question of design. Even when the outcome of a player's choice is not to score points, gameplay tends to interfere with otherwise weighty decisions. Once again, Mass Effect offers a prime example.

One of the game's most memorable moments comes near the middle of the story, when Commander Shepard and his allies travel to the planet Virmire to attack the base of Saren, the antagonist. The player -- through Shepard -- is confronted with a tremendous choice at the climax of this mission: to succeed and allow the rest of the team to escape the planet, one of Shepard's teammates will have to stay behind on a suicide mission.

The two party members the player must choose between are Ashley Williams and Kaidan Alenko. There is no way to save both of them, and each character insists that the player rescue the other. There's also -- functionally -- no difference to the outcome of the mission. Without any circumstances to affect the player's decision, the choice becomes about which character the player would rather keep around.

The difficulty lies in the fact that neither character is remotely sympathetic: Ashley is "toxically racist" in a group of mostly non-humans, and Kaidan is remarkably bland. (In a survey taken in mid-2010 on several Mass Effect forums, both characters received fewer "Love" and "Like" votes than any other character in the game, and Kaidan received special mention as the "Most Meh Character" of the series.)

Plus, neither character's skills are terribly indispensable in combat: other party members cover similar bases, and more effectively. Depending on the player's build, either Ashley or Kaidan may be important to their general strategy, but likely not both. It is also possible that one character or the other could be a romance interest for Shepard, but again, not both at once. The choice is dominantly a gameplay one, not a moral one.

This choice is popularly discussed as one of the most momentous decisions a player can make in a game -- any game -- even though it lacks much real weight. Perhaps the significance of the choice arises from the very real gameplay consequences of it: since gameplay is how players interact with the game, the decision feels non-trivial. That is not an irrelevant achievement, but nor is it the same achievement it appears to be.

None of this is to say that these approaches are without merit, but there have been other, more compelling approaches to moral choice. The most effective title in giving the player significant moral choices, at least in recent memory, is Quantic Dream's Heavy Rain. There are several profound moments in the game -- indeed, it is essentially about choice and consequences -- but my favorite, I think, is "the Shark."

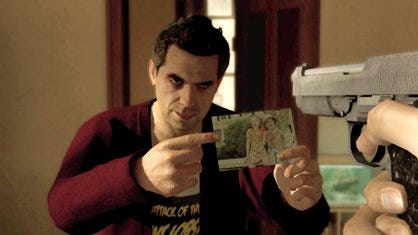

In the game, Ethan Mars must jump through a series of sadistic hoops set up by the Origami Killer in order to save his kidnapped son. The killer tasks Ethan with completing five "trials," each requiring a greater sacrifice; the third trial, the Lizard, requires Ethan to cut off his own finger. So when the Shark (the fourth trial) instructs Ethan, not to weather more physical torture or suffer additional dismemberment, but to kill someone, one of the most compelling choices in the game rears its head.

The Origami Killer has given Ethan a target. He's not a nice guy: a drug dealer, clearly dangerous, and probably not the sort of person that anyone would miss. Ethan has his address and a gun, and the dealer doesn't know he's coming. If he kills the dealer, he's one step closer to rescuing his son. If not, he's risking his son's life.

It is worth noting at this point that, unlike the previous games discussed, Heavy Rain only has a handful of game mechanics; they don't change, and no power ups, equipment, or character statistics that affect them. These factors are removed from the equation: no matter what decision the player makes, it will not change her effectiveness in later gameplay sequences.

During the Shark scene, Ethan -- and, consequently, the player -- has several opportunities to back out of the trial. The first is at the dealer's door: the man answers and is hardly welcoming, and Ethan can pull his gun and push his way in, or he can choose not to and leave. The latter choice is self-explanatory: the trial ends, and the story proceeds. There are consequences later in the story as a result of Ethan not playing along with Origami's game, but these consequences are not insurmountable.

Oh, yeah. He's a father too.

If Ethan does force his way in, the dealer realizes that something is wrong quickly enough to pull a shotgun. The pair get into a running firefight through the dealer's apartment. After this gameplay segment, Ethan has the upper hand. The dealer is on his knees, at Ethan's mercy. At this moment, Ethan can execute the dealer -- or not. The game is clearly asking the player, "Would you kill one person to save another?"

The decision is profound, and there are valid reasons for going each way: the climax of this scene even happens in the bedroom shared by the dealer's young daughters, revealing that he has a family -- a fact Ethan did not know. The game can be completed whether or not Ethan kills the dealer, but not killing him is a risk. I've spoken to a roughly equal number of players who chose each. (I spared the man; I thought the ends did not justify the means, but more importantly it made me think about the decision.)

But Heavy Rain's approach has its problems. For one, the game is highly atypical; it has limited gameplay and no real lose state. Some would argue that it isn't a "video game" at all, but an "interactive drama." To make the Shark and other situations hit hard, Heavy Rain has to spend a lot of time on the kind of dramatic buildup and character development which fits better in film, television, or prose.

But Heavy Rain looks like a game, and thus some players expect it to have a win state, a "right answer." The game takes great pains to convince the player throughout that any outcome to any given scene is okay: later events may change, but there's no wrong series of events, and the game will not end prematurely because of any choices the player might make.

But some players -- and I can say this with authority because my parents are amongst them -- have difficulty breaking free of the idea that the goal is to win. For them, they saw Origami's trials as win conditions, as objectives that had to be completed in order to beat the game. And in the context of Origami's game, they are -- but not in the broader context of Heavy Rain. The rules of the "game within a game" are not the same as those of the game itself. Despite this, my parents didn't really consider sparing the dealer, as they were under the impression that killing him was necessary to avoid losing.

Heavy Rain accomplishes the objective of giving players significant moral decisions that feel like they are significant, that have emotional impact, and that avoid a dominant moral strategy. Clearly, though, its method is costly, and could not be duplicated in most game genres. Heavy Rain is a compelling example of a rather niche genre, but where does that leave video games at large?

Though the consistent success of BioWare's role playing titles has set the standard for game morality models, games before and since have experimented with other methods that, like Heavy Rain, arguably avoid the dominant moral strategy problem.

One example is Tactics Ogre: Let Us Cling Together, the predecessor to the better-known PlayStation classic Final Fantasy Tactics. Like other titles in the Ogre Battle series, Tactics Ogre has a broadly-branching narrative with potential for dramatic variation in events depending on the choices the player makes at certain key junctures.

The first such juncture arrives when the player's allies decide to massacre the citizens of a small town and frame their enemies, intending to solidify support for their rebellion and make it possible to ultimately overthrow the current tyrants.

The player has the option to either go along with this plan or oppose it. This choice dramatically changes the course of the game's middle section and the choices the player will face later. It does not sacrifice any mechanical or gameplay benefits or advantages that the player has already earned.

There are different recruitable characters and items in each path, so players who prefer to look ahead via an online resource (or who have played the game at least once before) might choose based upon these factors, but they are non-obvious. Also non-obvious is the amount of separate content in each path.

Choosing not to participate in the massacre, for instance, technically cuts the player off from content, but also opens an equal amount of content.

The fact that the gameplay is largely linear, moving from mission to mission without much room for deviation, hides this fact better than a quest log, where the lack of a quest (or the presence of a quest the player might choose not to complete) confirms the presence of content yet to be experienced. The player, therefore, does not feel obligated to perform missions that are counter to their moral direction for the sake of the content.

More subtle (and more recent) is The Witcher, another title in which the player must make several choices that have far-reaching effects. These choices are important, but won't change the course of the entire game; however, the specifics of key events, and the characters who remain present throughout the game, can change dramatically over the course of the main, relatively static, plot.

Though the game is an action RPG with many similarities to some of BioWare's titles (not insignificantly, The Witcher uses a modified version of the engine created for BioWare's earlier Neverwinter Nights), it lacks any quantified morality elements.

The choices are not so black and white: an early situation involves an angry mob who wishes to burn a woman they suspect is a witch for cursing their village. The player can choose to side with the mob or the witch, and may well have to make this decision without knowing the facts. This choice will affect the immediate situation, of course, but will also have consequences, good and bad alike, much later in the game. These consequences are not based on an overall morality score, but on the specific choice that the player makes.

Part of the reason this functions reasonably well is that the player character, Geralt of Rivea, is given more definition than in many role playing games. He has an existing personality and morality, and any options that the player has in the game's many conversations are within a certain range of Geralt's grim pragmatism.

But whether by accident or design, this does not get in the way of the player making these choices for Geralt; there are not situations in which Geralt would obviously take a certain action, and often he appears to hate being put in a situation where he has to make such major decisions - but he's also able to rise to the occasion. (We can see a similar trend arising in Mass Effect's Commander Shepard and Dragon Age II's Hawke.)

But all of these solutions are, at a certain point, intractable. Branching narrative multiplies the need for content rapidly. High-end games like Heavy Rain, as a result, are generally quite short for one play. Titles like Tactics Ogre, which uses 2D sprites and limited character animations, are able to pack in more content, but still can only branch so much before the game would be nearly impossible to complete in a reasonable amount of time. The Witcher has the same problem.

Furthermore, as we can see, all of these games make substantial use of characterization for the main character, rather than leaving that character open to be defined by the player. The player can certainly shape the characters somewhat, but they are not able to make a character from scratch, however they want, as is popular -- and increasingly expected -- in role playing games. This will not drive players away in droves, by any means, but ideally significant moral decisions could be implemented with the necessity for such an avatar.

Clearly video games have been trying to give players meaningful moral choices for quite some time, but the solutions remain imperfect. It's no simple design matter. The difficulties that arise, when games try, appear varied, as the previous examples demonstrate. But the key problem is singular: context.

The BioWare model used in Mass Effect and other titles allows for a dominant moral strategy because of the gameplay implications of the player's moral choices. That is, BioWare puts the choice in the wrong context. Each choice becomes not an ethical decision, but a gameplay decision. They share their context with character build and combat tactics (amongst other things).

This extra layer of strategy may make these games stronger as gameplay experiences, but the moral aspect is really just window dressing. The difference between these choices and, say, which weapon to equip to a character is largely semantic.

The advantage to this approach is that gameplay is the context: the game does not need to spend additional time and assets to set the stage for the choice. The player will be familiar with the way the game works already, and so understands the implications of the decision and its consequences.

Insofar as this makes the decision meaningful to the player in some way, it succeeds. Perhaps, since games are already abstractions of the actions they approximate, this moral abstraction is acceptable, too.

In fairness to BioWare, the approach it takes with the Dragon Age series is, while still mechanically defined at its core, stronger. Rather than saddling the main character with an alignment measure at all, the Dragon Age games instead track how much the party NPCs like the player character.

Actions a character agrees with will raise this Friendship rating, while actions he or she disagrees with will lower it, and there is ample opportunity to make up for past disagreements.

The benefit to maintaining high Friendship scores is access to some minor statistical buffs for the character in question -- helpful, but not dramatically so. The significant choices, then, feel somewhat more divorced from the game's mechanics than their Mass Effect counterparts. (Frankly, I also believe that the strength of Dragon Age's writing is simply much better than Mass Effect's, resulting in far more compelling situations regardless.)

The context of choices in Dragon Age is twofold: primarily, they are placed within the context of the world and the story, and secondarily within the context of the player character's relationship with the party NPCs.

More narrative-focused games like Heavy Rain approach the problem of context from the other direction. They do all they can to invest the player in the game's story and characters so that moral decisions can be significant in the context of the characters they affect.

This is truer to the situation at hand -- the player can base his decisions on the facts they possess, not a gameplay strategy -- but it takes a great deal of effort to reach that level of investment. The method is, therefore, high-risk: many players simply don't have the patience for the amount of narrative this usually requires, and those that do may still not actually become as invested in the game narrative as the designers intend. Making anyone care about fictional characters and situations is difficult at the best of times.

So this context needs to change. The gameplay context tends to overwhelm the moral concepts at play; meters like Mass Effect's, or even out-of-game achievements, "invariably guide players to push to one extreme," as Louis Castle observed. Even just tying the morals to the gameplay tends to boil game morality down to using violence or using more violence. But a fully dramatic context is largely impractical; the execution alone adds huge costs in time and money to the development of an average contemporary game release.

Building context can be hugely time consuming and difficult to achieve fluidly. That is the strength of a mechanical context: players will learn the game anyway. A narrative context --whether a choice is significant to a character, a plotline, or the entire game world - takes more effort, and requires that the player buys into it in the first place. RPGs like Dragon Age or The Witcher have the luxury of side quests to build this in small pieces; besides, players expect a great deal of narrative content from that genre and will generally forgive it.

Other genres have it harder, though, because they do not have this advantage. Players of first-person shooters, for instance, would likely never put up with Mass Effect's encyclopedic codex of background info. This does not mean that there is no way to give such genres a thoroughly narrative context.

The obvious (and easy) answer is to use cutscenes and in-game dialogue to tell the story, both of which have ample precedent. But there is also an immense amount of power in a game's setting: this is the environment a player will actually be exploring throughout, and with the current graphics capabilities of game consoles the sky is arguably the limit. Consider BioShock: the environment of Rapture alone does so much narrative work that a discussion of it would easily warrant its own essay, and then some. Immersive worlds like this encourage investment.

Of the titles I've discussed, I would argue that The Witcher gets nearest to a solution by hybridizing the systematic and narrative contexts in subtle fashion. There is no meter, no clear quantifier for the player's morality, but there are (eventually) gameplay rewards in the form of items and assistance for certain actions.

There is substantial narrative context for the game's decisions, but most of this is revealed piecemeal during quests, not through lengthy (and expensive) cutscenes. In essence, the game is player-driven, rather than system-driven, at least in this respect, but to allow a meaningful amount of flexibility within a game's design constraints, the game itself must sacrifice some fidelity.

Like The Witcher, Infamous uses largely static, but stylized and attractive, images in lieu of pre-rendered cutscenes.

Indeed, reducing the overall fidelity of a game in exchange for additional content could also allow for a return to some advantageous methods of past games. In the late 1990s, it was in vogue for RPGs to include literally dozens of characters -- far more than a player could ever need or want in a single play through the game.

Games like Baldur's Gate forced the player to consider her actions in the context of the party he had built as much as anything, and characters were free to leave (and die) when their differences became too heated. Party sizes shrunk again dramatically over the years as games were increasingly expected to deliver characters with fully 3D models, complex animations, and full voice acting. So much effort is put into a single character in a modern RPG that players are left with little party flexibility in the long run.

We need to be able to step back from the sort of gee-whiz technical achievements that characterize AAA titles these days if they won't add much to the game experience. Strong art direction can do as much, or more than, high polygon counts. If we want to see video games move beyond increasingly complex struggles for high scores, we need to be willing to consider qualitative, not quantitative, approaches to game concepts, at least on the surface. We need not just game designers, but experience designers, writers, and world builders.

Morality is incredibly complicated. The fact that learned individuals have debated it for as long as we can remember is testament enough to that. Engaging such a dilemma is not going to be as simple as assigning a number to it. Really, truly tackling this complex topic will require an equally complex solution with lots of moving parts. But I think we have the tools; we just need to apply them.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like