Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Detail Mechanics

The moments that stick with us are often small game mechanics that expand and complement the system of a game world.

It seems that we usually point to details when we talk about games we love. Those little moments that work within the context of the greater piece of work and enhance a game's atmosphere. I wanted to highlight the small details of certain games that strengthen the core mechanic and mood of said game.

When I look at the following details, I think about the context in how these elements came to be? Were they constructed out of a need to teach, out of a desire for additional depth, or to create a certain emotion?

Minecraft - The Creeper

The creeper is my "duh!" example. It is widely loved/hated by players, and one of the most recognizable creatures from gaming's last five years. I believe it has this popularity because of how tightly it is integrated with the system's mechanics. It's a bob-omb, after all, in a world where, unlike Mario, creation and destruction are the foundations of the system.

When you hear that threatening hiss, it signals the end of procedural and constructed perfection. The creeper is a potential end to the patterned glass wall you spent twenty minutes designing. Waiting just on the inside of your door, watching that pixelated face stare back at you. Almost stupidly simple, the creeper amplifies how easily any terrain can be affected.

How many times have I barely escaped explosive death out in the wild and then, out of compulsion, replaced every cubic meter of sand a creeper uprooted? I have the power to undo its evil upon a perfect procedural wilderness. The creeper is a cruel reminder of the time we spend within Minecraft's ruleset.

Deathspank - Loot Names and Descriptions

This game held my attention all the way to completion, and I attribute that largely to the wonderful writing. It has a fun core loop, but nothing overly original. Where the game and the writing meet wonderfully is in the naming of loot. You can find the Bladed Shoulders of Blades. There is a Bad-Ass Crossbow, that's been "carved from a wicked donkey". Or the Log Sword, the description being: "A sword with a log on it, or is it a log with a sword on it?"

Deathspank's art is solid, it is a cool world with a clever storybook terrain, but the images of the weapons are almost generic. The names and descriptions speak volumes more. The discovery of new weapons, and what is the mega-bad-assedest of weapons, kept me going in a game that is otherwise unsurprising. I relished when those descriptions even tied further back into gameplay, when I had to use a Poop Hammer to literally "Kick the poop out of any demon."

The game's writing was exactly what I want from games, concise and human. And I don't know if I have ever laughed as hard playing a game as when I first fought a Swamp Donkey. Writing, in this case, is integral to the game's mechanics. Like many adventure games, the game is ultimately about exploring the wit of the writer[s].

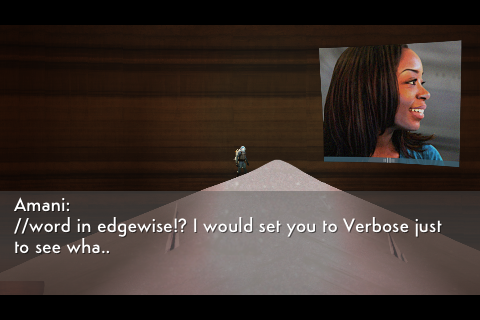

Waking Mars - Speaking to Amani

While we are on the subject of writing, Waking Mars has a feature that works well in function and form. As you get deep into the caves of Mars, you discover a large vertical cave. So large, in fact, that it somehow amplifies and allows your comm device to reach your partner, Amani, down at base camp who you can normally only contact from near the planet's surface. Amani tells you to return to this cave any time you want to talk to someone. She's a bit lonely and you guys have plenty to talk about.

People have responded to this feature, after they find how affected they are by the game's solitude. You are a lone character descending into a network of caves and you are limited to only occasional communication with your suit's computer. In a game that can span six or seven hours, giving the player a place to initiate conversation with another character ends up being surprisingly powerful.

Not only that, but Amani will help with clues about what you should be doing. This space ends up being a really cool hint system that is the game talking to you when you may need it. In a game that remains reasonably vague about the world, this detail mechanic ends up complementing the mood of the story, remaining thematic, and allowed us, as developers, to help the player within the confines of the world.

A few other bits and example mechanics

FEZ - The usage of Tetris shapes throughout the game as puzzle and architectural elements amplified my already overflowing curiosity about what everything might mean.

Dark Souls - Crossing narrow walkways in the game wears you down, as if you are not already tested to your limits.

Just Cause 2 - Setting off triggered explosives as you free-fall makes you feel like an action-movie star. Every single time. (For me, at least.)

-

So what do I draw from all of these? When creating a mechanic, you should question your sub-mechanics within the context of your overall system. It ended up a bit ludicrous, but jumping all around Morrowind until I could leap from building to building still made sense to me, in the idea that I had spent all my time "training" as an acrobat and jumper. It seemed more logical than adding some theoretical points to a list of stats.

When making a game with guns, why are so many games about only shooting the gun and pressing R to reload? Detail mechanics could enhance the heft and meaning of the gun, and a game like Cactus's Norrland makes reloading its own mechanic that I got surprisingly good at. I became uncomfortable at how over the 30 minutes of playing the game I went from slow and awkward while reloading to chillingly quick. Shik-snik-click! I felt like a killer because Cactus forced me to spend time reloading my hunting rifle.

I want more of these things. If you think about your mechanic beyond genre conventions and reexamine why you make each mechanical decision, I firmly believe you will find a plethora of alternative mechanics to create RPGs or construction sims or racing games or any other type of game. And these things will make you stand out, they will make me take notice and remember how I felt playing your game, caring about what I was doing.

Randy is an indie developer/artist who shipped Waking Mars recently with Tiger Style Games and also makes his own games, namely his iOS masterpiece Dead End, which you should totally buy for a dollar! You can also follow his ramblings on twitter.

Randy's new game Total Toadz, made with a couple of friends, is totally about to ship!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)