Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Designing puzzles for adventure games - Analyzing Monkey Island 2 puzzle dependencies and balancing

Marcus writes about puzzle design for adventure games and, to do so, analyzes Monkey Island 2 puzzles.

I think (classic) adventure games are really challenging to design because they consist of so many elements you have to pay attention to. One very central element of such games are puzzles, because adventure games are basically story-driven puzzle games. And believe me, good puzzles are not easy to design. How do you even start? And how can you ever know that your puzzle chains are good before you build a prototype and let people play a very rough and at no point ready to be played game? What is a good balance for scenes, characters and the number of puzzles the player has to solve? Writing puzzles for an adventure game is demanding and requires a really good sense for the intended game experience you want the player to have. Puzzles should neither be too easy nor too hard. The player should have to do some thinking to get to your puzzles’ solutions, but the puzzles should always stay logical and reasonable. Nothing in the world is worse than having the players solve puzzles just by accident and thinking they would never have guessed the solution because it’s just illogical - at the same time your puzzles SHOULD be creative, crazy, surprising. So writing good puzzles is kind of a fine line.

Recently, grumpy gamer and Monkey Island creator Ron Gilbert wrote a blog post about something he calls Puzzle Dependency Charts. Using those charts is an approach to writing puzzles for adventure games Ron and his colleagues apparently used back at LucasArts when they designed the puzzles for their brilliant games. When we started designing the puzzles for our soon-to-be-announced adventure project we used almost the same method. I recommend all of you to have a look at Ron’s article, because what he describes is a very useful technique to write puzzle chains. As Ron explains, you immediately see the linearity and parallelism of your game’s puzzles, which turns out to be very helpful.

But still, what makes a good puzzle chain? How can charts and graphs help you get the right feeling if the puzzles you wrote work as intended concerning the overall game experience? To approach this issue, it makes sense to have a look at successful adventure games, especially those where the puzzles seemed to be extremely good. I could name many games to which these criteria apply and it certainly makes good sense to analyze a few games or puzzle chains - but for now, let’s stay with one example. For this purpose, I untangled the puzzles of a very successful game with really good puzzles: Monkey Island 2 (yes, you have to know the game to understand the rest of this post. But I guess nearly everyone who is interested in this post knows the game). Remember when you have to find the four map pieces in the second part of the game? You can travel three islands at once, meet lots of characters, collect a load of items, and still… everything works out just fine. The puzzles are creative and sometimes kind of insane. Why do they work out so well?

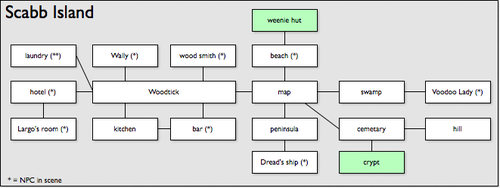

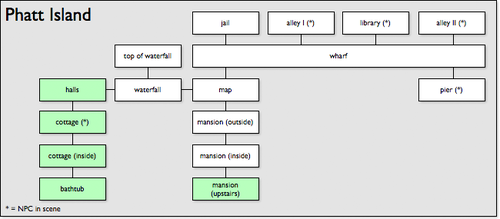

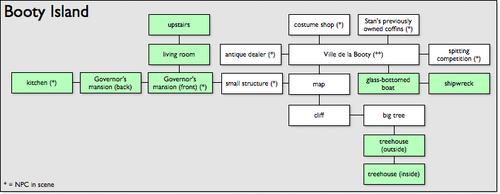

When you start part 2 of the game, you can travel to Scabb, Booty and Phatt Island. Scabb has been explored in chapter 1, so the places and characters are (almost) known. But how many scenes can you actually visit and how many characters can you interact with? You will definitely ask yourselves these questions when designing your own adventure game. So let’s have a look at the maps of the three islands at first (click to enlarge):

I colored rooms you can’t reach at first in a mint green color. Because, at the beginning, you are not mint to be there. Ahem. I also indicated the number of characters you can interact with in the rooms. Let’s sum it up: the players is able to visit 62 locations and interact with around (because I was a little vague here) 24 characters. BUT: The player already knows 16 scenes (on Scabb Island). So, we have 46 new rooms. 16 of those are initially not reachable (and this is important - getting into new rooms is a reward for an adventure player in the game). All in all, the player can visit 30 new rooms when chapter 2 starts. He can then interact with roughly 9 new characters.

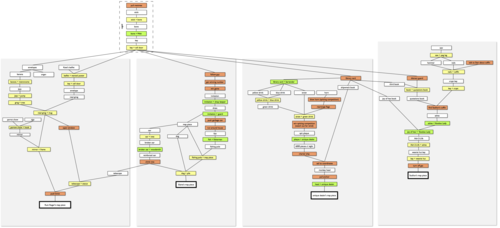

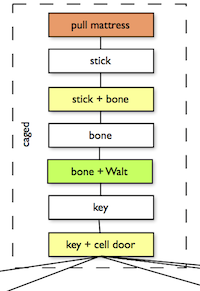

Alright, we have the numbers. Let’s dive into the puzzle thing. When you surf the internet, you can find a lot of definitions of how many different types of puzzles classic adventure games make use of. As always, people have different approaches and opinions. For the beginning, let’s just stick with this simple differentiation: Guybrush finds and collects items (white boxes), he combines items with items (yellow boxes), uses items with other characters (green boxes) and he interacts with the environment or characters (red boxes). I’m aware that one could classify puzzle types in lots of other ways and that there are pros and cons on every classification approach - but let’s just stick with this way and talk about classification of adventure puzzle types another time.

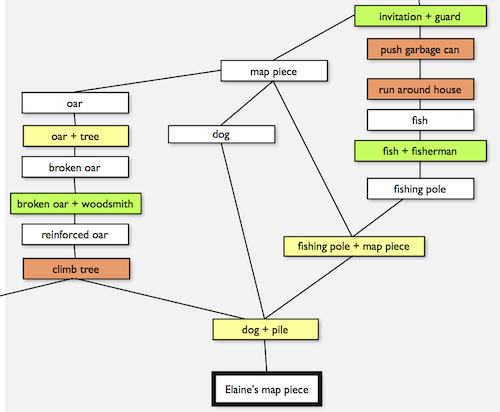

Okay, you asked for it! Let’s have a look at the puzzle dependency chart (using color puzzle type differentiation) for the map piece puzzles in Monkey Island 2 (click to enlarge):

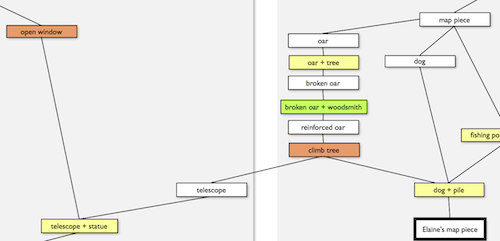

Woah. What a beauty. Do you see the parallelism of the puzzle chains? Do you see how one can obtain the map pieces nearly independently from each other? One can find lots of information in this chart. Let’s have a closer look:

One of the first things that catches one’s eyes is that you have to visit Phatt Island (where you are being put in jail at the beginning) of almost every puzzle chain. Why did I always sail to Booty first? What a rookie mistake. The invitation to the party is essential for Elaine’s map piece and starts the whole puzzle chain. Without the library card, you can’t solve any puzzle in the puzzle chain for the map piece the antique dealer owns. The other two map pieces are connected to a start on Phatt as well. What happens when you stay on Scabb or go to Booty? Besides new dialog options, you won’t discover new things on Scabb Island. On Booty, you can talk to people, you can collect a few items. But you won’t get too far. The game seemingly leads us to Phatt Island in a magical way or something. Guybrush is being arrested instantly when arriving on the island and the player finds himself in what I call a caged situation.

See, it’s always good when a game or a section of a game starts off easy and then, when the player knows his craft a little more, gets more difficult. A caged situation in an adventure game is an easy situation almost all the times. You have restricted capabilities and the things you can interact with are ready to hand. The chapter starts with a nice, easy puzzle where you have to escape jail. Then, and only then, you are able to get the invitation and the library card which are the two essential items that start the puzzle chains for Elaine’s and the antique dealer’s map pieces. The banana and the possibility to move freely on Phatt Island are essential for the Rum Rogers line of puzzles. The puzzle chain for Rapp Scallions’ map piece is also depending on the ability to explore Phatt Island. Monkey 2 part 2 starts off easy in a caged situation and then sets the way to four parallel lines of puzzles that the player can work on simultaneously.

As you can see, map piece 1 (Rum Rogers) and 2 (Elaine) are slightly connected by the ability to climb the tree and piece 3 (antique dealer) and 4 (Scallion) are connected by the library card. When designing parallel solvable puzzles, keep an eye on your puzzle dependencies and try to keep them independent from each other. You can see how the four map pieces are mostly puzzle chains for themselves. But you can also see, small dependencies are not wrong. There is a fair chance that these dependencies are there on purpose.

A good example for parallel puzzle solving can also be found in the Elaine puzzle line. Once you get to the party, you can collect (and lose) the map piece and you can steal the fish. These actions can be done independently from each other, but they lead to the same puzzle in the end. You need the fisherman’s fishing pole to get the map off the cliff. You then need to get on the tree. To do that, you initially need an oar - you can only get that once you have stolen the map piece. And all comes together. Take some time to study puzzle dependencies and parallelism in the chart.

You will also discover that the different puzzle types are very well balanced and distributed. You barely only have to combine items in a row (it looks a little only-white-yellow-ish in the Rum Rogers line, but in between these puzzles you walk ways and talk to Rum Rogers and you discover new rooms there all the time - one has to keep that in mind, too).

Did anyone count the items that are involved in the four puzzle chains?

Rum Rogers: 10 items

Elaine: 9 items

Antique dealer: 9 items

Rapp Scallion: 10 items

Well, that is pretty balanced. And it’s a good advice again: when you try to design parallel puzzles, and you want them to be equally difficult, try to keep the number of items, characters and rooms to visit in balance. And remember not to connect them too much, only if you want or feel they have to be connected.

All in all, the part has four major puzzle lines, barely connected, with around 40 items, 46 new rooms and 14 new characters. Maybe at some point when designing an own adventure game, you need some advice how to balance all these elements. You can try to orient yourselves on these numbers. Always keep in mind that other factors like story, setting, intended, difficulty, and so on influence the number of items, rooms and NPCs.

Do you discover more useful advice for ongoing adventure game developers in the Monkey Island 2 puzzle dependency chart? Do you have handy tips yourselves or do you think puzzle charts don’t help when designing adventure games? Feel free to leave comments and discuss!

Thanks to Worldofmi.com for reminding me of the Monkey Island 2 walktrough. :)

Marcus

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)