Designing games to teach Soft Skills (Part 2/4- Advantage in game based learning)

How training methodologies can be adopted by a wide range of professionals and purposes to enhance traditional training practice, boost participants’ learning experience, heighten participants’ self-awareness and self-confidence and facilitate knowledge.

Designing Games to Teach Soft Skills and Learning Soft Skills by Playing Video Games

Part 2: Advantage in Game Based Learning

Part 4: Personal Suggestions and Conclusion-->

2. Advances in Game Based Learning

2.1 Gaming Experience and Education

There has recently been a great deal of interest in harnessing the motivational qualities of games in order to create powerful, engaging educational and training tools (Amory et al. 1999; Gee 2003; Garris et al. 2002; Brown 2014; Moreno-Ger et al. 2014; Riemer and Schrader 2015). This interest is unsurprising, given that games are carefully designed to engender user engagement (Dondlinger 2007; Mayo 2007) and that engagement is also a key predictor of success in any educational or training program. Indeed, motivation is consistently found to be a key predictor of successful educational outcomes (Malone 1981; Filsecker and Hickey 2014).

Specifically, the amount of time a student spends engaged in learning (or time-on-task; Admiraal et al. 1999; Fredrick and Walberg 1980) has a significant impact upon her learning. At the same time, games are a form of technology that specializes primarily in engaging and motivating users to spend time-on-task (Dondlinger 2007; Mayo 2007). The prospect of a form of teaching that inspires engagement on similar levels to those observed with computer games is very attractive to educators.

Moreover, learning is also an essential part of successfully playing any game (Gee 2005; Koster 2013; Rosas et al. 2003). Indeed, all commercial games are educational to some extent, because they force players to learn the skills needed for gaining success within that game. When playing any game, it can be said that players demonstrate complex behaviors after a period of playing that they would have been incapable of performing before they started playing. Entertaining games require players to learn (Gee 2003), and those players engage in this learning willingly. It seems that game designers have hit on profoundly successful methods of getting people to learn and to enjoy learning (Warren et al. 2009; Warren and Dondlinger 2008). For this reason, most of the successful game-based learning experiences have used mainstream games like Civilization, the Tycoon sagas or The Sims.

Fig 1. Image from gameplay of Zoo Tycoon, developed by Blue Fang Games and published by Microsoft Studios. Player owns a zoo, constructs it, maintains it and takes care of it as a zoo keeper.

However, despite their educational potential, most mainstream games lack integration with the current curriculum and appropriate assessment frameworks. As an example, in real-time strategy computer games like the RollerCoaster Tycoon saga, Virtual U or SimCity saga, players adopt the role of business managers and have to take the management decisions of an organization.

Fig 2. Image from gameplay of Sim City, developed by Maxis and published by Electronic Arts (EA). Player builds city with provided budget on an empty map.

For example, in Roller Coaster Tycoon, the goal is to build and administrate a theme park that is profitable. The potential of these games is almost evident because they can help students in developing highly valuable skills like resources management or decision-making, but it is uncertain if this will result in a better performance in exams and, as a consequence, in a tangible academic improvement.

Fig 3. Image from gameplay of RollerCoaster Tycoon, developed by Chris Sawyer Production and published by Atari. Game simulates amusement park management.

We will talk about more examples in later section.

Nevertheless, the advantage of using mainstream games is clear: teachers or educational institutions only need to go to any retail store and purchase them, without the need of creating a new educational game. Indeed, creating a game is a time-consuming task, so in an already time-constrained curriculum where educators are usually struggling to achieve the goals defined by educational regulators and institutions, the question is “Is it worth taking the time?”

Notwithstanding, there are clear benefits that come from using custom games developed directly by educators instead of using mainstream games (Prensky 2005). Indeed, mainstream games are developed to be entertaining, not educative. They provide contents that are rich and valuable from an educational perspective but also include errors, misconceptions and inaccuracies to make the games more attractive. This is usually a concern that parents show when they are told that their kids will be using games in the classroom. In addition, mainstream games are not always easy to align with current curricula or do not meet educational standards.

Educational games appear to offer the potential to improve learner motivation, time-on-task and, consequently, learning outcomes. There are a number of reasons behind this view, which have been highlighted in many recent books and scientific articles (Aldrich 2005; Hussain and Coleman 2014; Giessen 2015; De Gloria et al. 2014). The main pedagogical element that stands out is that users experience the game in a direct, not mediated way. By simply playing the game, sometimes with the help of a light tutorial, the user can acquire the game dynamics, its foundation concepts and the entire body of knowledge necessary to progress deeply in the game and experience more advanced features.

2.2 Traditional e-learning vs game based learning

According to [9]:

Traditional e-learning | Game Based learning |

|---|---|

Offers content of little use | Engages your people with an innovative and fun type of training. |

Does not facilitate experiential learning | Turns learning into an adventure and motivates your employees. |

Only 25% of students complete their courses. Is boring. | Implements a training solution with real impact on your organization and the image of your department. |

We throw away 3 out of every 4 dollars invested in traditional e-learning! | Integrates high quality training into your Learning Management System at e-learning prices. And improves your completion ratios! |

And we get frustrated in the process. | And make your people enjoy training again. |

2.3 Designing games to learn

According to the book, the approach used by the author to design games reflects two main dimensions: psycho-pedagogical and technological, which should not be considered as mutually exclusive dimensions but rather as complementary.

The first dimension specifies the psycho-pedagogical foundations of the learning approach adopted and identifies two main categories of education games:

Drama-based: Drama-based game allows users to experience direct involvement with the learning objectives through a personal dramatization by acting out roles and competences. Drama-based games are based on informal rules and open dynamics; therefore, there is not a unique way to achieve the desired learning objectives. This will depend on the specific situation in terms of aims and peculiarities of dynamics occurring among people involved in the specific game scenario.

Rule-based: Rule-based game points more on the logical and reasoning aspects involved by the user for achieving a specific learning objective. A set of formal rules and interactions embedded in the game needs to be followed in order for learners to achieve the relevant learning objectives.

With regard to the second dimension, educational games are substantiated by the use of two main technological systems. One allows a virtual extension of traditional face to face psychodrama-tic mechanism and experience that is transposed to a digital setting. A second technological approach permits the production of “artificial” micro-worlds based on computer-simulated, formal models about social and psychological phenomena. We will refer to the former dimension and to the education games that predominantly exploit it as Communication Technology (ComTech) and Simulation Technology (SimTech) based.

2.4 Structure of Educational Role-Playing Games

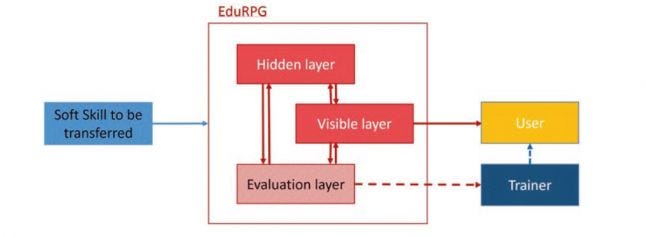

Irrespective of their technical implementation and application domain, all educational games share general features that can be found in every psycho-pedagogic role-playing game. Their fundamental structure can be viewed as the combination and interaction of three layers: (a) hidden layer; (b) visible or external layer; and (c) evaluation layer.

Fig 4. Image taken from book [1]. Fundamental structure and functional elements of an EduRPG with their relationships. The starting point is the soft skill to be transferred through the game. EduRPG designers must work on three different levels: hidden layer, visible layer and evaluation layer. Dashed lines represent the information flow of the EduRPG when a trainer or tutor is present.

2.4.1 Narrative Structure and “Mise en Scène”

According to Barthes (1977), narrative is a pervasive feature of human cultural products and can be found in myth, legend, fairy tale, novel, epic, history, news, cinema, comics and, obviously, games. Speaking in terms of literary concepts, the relation between the visible layer and the hidden layer can be likened to the relationship that links the narrative of a novel, a theatrical representation or a movie, with the underlying narrative structure and moral of the story, that is, the development of the story itself and the message conveyed. It is possible to make an association between the overall narrative structure and moral of the story with our concept of hidden layer. Indeed, this holds the constituent elements of the story and represents the hidden elements and the meanings upon which the training game is realized. Therefore, it is fundamental that the hidden layer embeds the psycho-pedagogical elements necessary for a successful transfer of the soft skills to be trained. As we will see later, the hidden layer in educational RPGs is usually based on certain psychological assumptions, similar to those assumed by the traditional role-playing games, often inspired by psychological theories pertaining to the training objectives and by pedagogical concepts.

Educational RPGs, as many other cultural products, are expressed through a narrative metaphor, so it is important to define those visible elements as instrumental for establishing the correct sets of experiences to be implemented for the benefit of the user. In particular, this means defining the plot, scenario, characters, roles and overall setting of the game. This layer is where the training context is defined: who are the characters, what actions they can perform and what kind of interactions is possible between characters. The characters can be the leader and the employees in a company or a group of students in a classroom. They can even be two armies on the chess board.

The visible layer, therefore, together with the overall narrative of the game, also contains what in cinematography is called “mise en scène”, which literally represents what and how the user will see the characters and the whole scene on the screen. This aspect is particularly important because it is the real front-end of the game and it offers a major contribution to the positive or negative perception of the user, which can in turn affect motivation and willingness to engage with the game.

2.4.2 Performance Assessment and Tutoring of Learners

Video games continuously assess the player’s level, and educational games should use similar techniques (Michael and Chen 2005a, b online cit.). In traditional games, the main assessment techniques, according to the book, are the following:

Tutorials: Tutorials introduce the player to the basic rules for interacting with the game and then test the player on them, proposing specific missions that introduce only a few game features and elements. Once the first tutorial missions have been successfully accomplished, the player can face greater challenges, until she has mastered the basic concepts.

Fig 5. Tutorial screen before a level of Angry Birds, developed by Rovio Entertainment

Level completion: This is the first indicator that the player has reached a specified standard performance within the game. Level completion allows us to say not only that player participated in a certain mission but also that she was able to manage it. On the other hand, the cons are that completing a level does not guarantee that the player has acquired the corresponding knowledge. Indeed, she could have just learned how to beat the game, for example, by cheating.

Fig 6. Level complete screen from Mario Game, developed by Nintendo.

Scoring. The scoring system teaches the player what is important within the game. After any action in the game, the player can observe its effects on the score. A positive effect indicates a good choice, a negative effect a bad choice, and no score indicates that the related action is probably not important. In this sense, scores correspond to grades in the classical educational context.

Fig 7. Score screen image of Tetris showing different score system.

2.5 Teaching and Learning Should Be Intrinsic to the Game

In order to make the training provided by Educational RPGs effective, it is essential that game mechanics, that is, the set of rules that define what the player actually can and cannot do when interacting with the game, must be integrated through an intrinsic link to learning contents. For instance, Habgood and Ainsworth (2011) have tested different versions of Zombie Division, a 3D adventure game that teaches mathematics to children through swordplay with skeletal opponents.

Fig 8. Image from gameplay of Zombie Division.

In the “intrinsic” version, mathematical multiple-choice questions were integrated into the combat system, whereas in the “extrinsic” version, they were put between levels, without any link to the combats. The authors showed that children decide to spend more time playing the intrinsic version because of the perceived link between game mechanics and learning content. This is an absolutely key point that has been missed in the majority of games designed for education. Indeed, educational software has traditionally used gaming elements as a separate reward for completing learning content, with no relation to the skill or knowledge being learned.

Indeed, in the early phase of “edutainment” games, it has been often used a kind of “chocolate-covered broccoli” approach (Bruckman 1999). The idea was to make learning content more fun and attractive by tagging games to it. However, such methods have often proved ineffective (Kerawalla and Crook 2005; Trushell et al. 2001), failing to effectively harness the engagement power of digital games. The reason, as already noted, seems to reside in the extrinsically motivating design models of such systems (Lepper 1985; Parker and Lepper 1992).

On the other hand, teaching and learning are usually intrinsic to gameplay in successful games. When playing an entertainment game, everything the player learns during her play is necessary for the fulfilment of some specific goal within that game, not for some objective outside it. For this reason, the way a game should evaluate whether or not players have learned should be through simply monitoring their play, not with a different modality such as a questionnaire. More in general, teaching, learning and assessment should be carried out solely through the core mechanics of the game.

From a pedagogical perspective, it is worth noting that, although the process of learning can be frustrating, the good performance of a recently acquired skill is incredibly satisfying (Lindsley 1992; Gee 2003). Educational games, like entertaining ones, should provide this opportunity to learners, simply by letting them play.

In summary, when training soft skills by means of educational games, we should link the learning outcome with the mechanics of the game we are building. As an example, if our goal is to teach leadership or negotiation, we should create a game that revolves around leadership or negotiation. And everything the player learns is learnt simply by playing, and rewards are given to the player inside the game.

2.6 Game Design Principles of Entertainment and Educational Games

Given the success of entertainment games in making people learn and practice for many hours, often dedicated to enhancing skills that have no other scope than making the player satisfied, it is natural to look at those games as successful exemplary implementations. Therefore, the potential of games towork as valuable training tools can only be fulfilled through a deep understanding of how entertainment games motivate engagement and learning. To engender the same motivation observed with entertainment games, and obtain successful learning outcomes, we should design our educational programs in a game like fashion, using the same principles and techniques adopted by commercial games.

The following is a short and an in-exhaustive list of features shown by most engaging games (directly taken from book [1]):

Games are complex, logical systems that allow interaction and trial-and-error learning (Randel et al. 1992).

While playing, players are constantly presented with a series of short-, medium- and long‐term goals (Swartout and Van Lent 2003).

Games let players improve their abilities in an incremental manner, starting from basic skills to more complex ones. Usually, players are not allowed to advance to more difficult levels if they do not show excellent performance in the current one (Loftus and Loftus 1983).

In order to reach their goals, players are typically required to take some actions or decisions during game play (Prensky 2001; Salen and Zimmerman 2003).

During their play, players are not afraid to make errors. On the contrary, they usually accept repeated failures until they reach their goal.

The level of autonomy of the players is high. Throughout the game, they take decisions and make actions in complete autonomy, although sometimes they can ask for help from other players (e.g. in dedicated forums).

Fig 9. Image taken from God of War, E3 2016 gameplay trailer.

Based on these principles, educational games should therefore:

Clearly define not only the ultimate learning outcome of the program but also intermediate steps that learners must reach on their way to the final goal. Once players have passed some level in the game, thus demonstrating mastery of some particular skill or knowledge, they should be allowed to advance to subsequent levels which build upon that newly acquired information. For each learning outcome, we should also define an acceptable mastery criterion.

In every phase of the game, the difficulty level should be high enough to keep learners engaged, but at the same time, it should not surpass their abilities, in order to avoid frustration.

Provide a personalized learning process according to the player’s profile. It is important to first assess the player’s level, her needs, learning speed and motivation, in order to create a learning path tailored to individual learners.

Part 2: Advantage in Game Based Learning

Part 4: Personal Suggestions and Conclusion-->

References

[1] Dell'Aquila, Elena, Davide Marocco, Michela Ponticorvo, Andrea Di Ferdinando, Massimiliano Schembri, and Orazio Miglino. Educational Games for Soft-skills Training in Digital Environments: New Perspectives. Switzerland: Springer, 2017.

[8] Role-playing game. (2017, June 16). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 19:28, June 21, 2017, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Role-playing_game

[9] "Game-based Learning Corporate Training." Gamelearn: Game-based Learning Courses for Soft Skills Training. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 June 2017.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)