Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

Case Study: Creating Witness a virtual reality experience

Witness is a virtual reality short I made in partnership with Warsaw Rising museum. It presents the story of an insurgent of Warsaw Uprising. This post describes key aspects of the design process that went into making Witness and what I learnt from it.

Witness is a virtual reality project I created as part of my master’s thesis in Computer Science from Polish-Japanese Academy of Information Technology. It tells the story of an insurgent of Warsaw Uprising, the largest urban insurrection in Nazi occupied Europe during World War II. Currently it’s a five-minute-long prototype that can be experienced through Google Cardboard and Oculus Rift DK2. The project was developed together with Warsaw Rising museum, one of the most popular museums in Warsaw today. Specialists from the museum helped me in researching the story and with usability testing of the developed prototype. In this post, I want to share key aspects of the design process and what I learnt while making Witness.

Some background first. I’m from India, living in Warsaw for almost five years now. As a foreigner, I’m fascinated by the city’s modern history, especially events of World War II that encompass Nazi occupation, the Holocaust and two major uprisings – Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943 and Warsaw Uprising of 1944 – during which most of the city was destroyed and majority of the city’s inhabitants were either dead or displaced. Today, Warsaw is a dynamic metropolis. Knowing the extend of destruction that the city had suffered, its post-war reconstruction seems nothing short of miraculous. While walking through Warsaw’s lively streets lined with cafes, restaurants and designer boutiques I have often asked myself what it must have felt like to live through the city’s destruction. Witness is my attempt to answer that question.

Design process

Once I started co-operating with the museum, the first challenge was coming up with a comprehensive narrative design. This was the first time I and my guides at the museum were working on a VR project, we had several ideas but not enough knowledge of what kind of narrative would work best in VR. Moreover, since I was the only person developing the VR experience, we needed be conscious about the practical limitations concerning duration of the experience and the scope of world building. After some deliberation, we decided to take five to ten minutes as the intended duration.

We started looking for a powerful story that would be able to render complex history of the uprising emotionally accessible to the audience. The story needed to be nonfictional, based solely on documentary materials. While searching, the museum’s audio-visual archive containing thousands of eyewitness accounts of the Uprising became our go to source. The account we finally chose concerns the experience of a twenty-four-year-old woman who worked as an editor and courier at the main underground news bureau during the Uprising. Her memoir, recorded by the museum in an hour-long interview conducted when she was over eighty, is emotionally moving and contains several interesting details of everyday life during the Uprising. Taking the stipulated five to ten-minute duration as guideline, I developed two short scenarios from her account. I wrote two scenarios since I was not sure about two basic aspects of the narrative – the time and the place, whether the narrative should take place during the uprising or after, in retrospect? Should I go for an indoor location (which would be simpler to build) or an outdoor space?

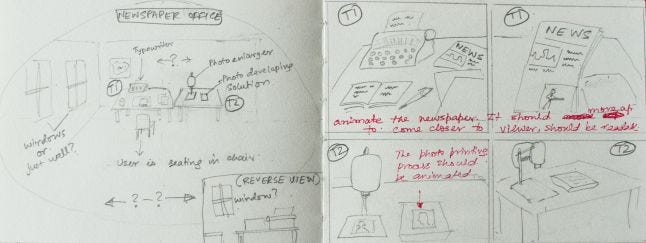

I used paper storyboarding as a tool of visualizing the scenarios. Though it helped me get a basic feel of the environmental design, visualizing a scene in 3D 360 degree from paper storyboard was more challenging than I had expected it to be.

Storyboard that eventually influenced design of prototype 1 – scenario 1

Storyboard that eventually influenced design of prototype 1 – scenario 1

At this point, I decided to dive into 3D prototyping using Unity. I chose Unity because of its ease of use, cross-platform support and a comprehensive asset store that contains tons of free as well as paid resources. At this stage, I was not sure which VR platform or platforms will be eventually used to show the experience. Owing to several factors that I don't want to get into this article, I was more inclined towards mobile VR in comparison to higher end stationary devices like HTC Vive or Oculus Rift CV1. I had a Google Cardboard headset and a compatible smartphone at home which I used for testing the prototypes. Later in the project (from prototype 2 onwards) I also used Oculus DK2 as a secondary testing device. I followed an iterative design process that included creating a prototype, showing it to museum experts, collecting their feedback and updating the prototype. In the end, the prototype passed through three iterations before taking the form of the final version.

Creating the first prototype

First version of the prototype has two scenarios. In addition to twin considerations of time and place, I added the element of interaction as a variable in designing them. One scenario narrates the story primarily in present tense (while the uprising is going on) in an indoor space through interactive elements. The other takes place in past – the user is thrust into a post-uprising ruined Warsaw, there is no possibility of interacting with the environment other than looking around in the 360-degree space. In the second scenario, I used edited audio fragment of the chosen eyewitness account as voice over track. First person VR narratives sometime use avatars or virtual hands to give the viewer a sense of embodiment in virtual environment. I didn't use avatars or virtual hands. I wanted the viewer to have a disembodied, almost ghostly experience, and in case of the second scenario the feeling of having accidentally stepped into someone else's memories.

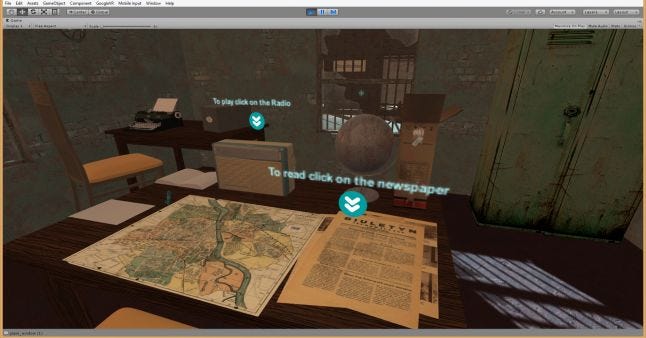

In the first scenario, the audience is placed in a virtual room containing interactive objects like an old radio, newspaper and photo printing apparatus. The audience is informed through a voice-over that she is standing in an underground printing press active during the Uprising. Interaction cues are provided through spatial UI overlay. For example, text message hovering over the radio prompts the audience to turn it on by looking at it for a few seconds. On being turned on the radio played recording of actual broadcasts made by WWII-era underground station. Battle sounds in background created the impression of being present during the Uprising, while voice over provided first person perspective on the historical reality of working in an underground press.

Screen print of prototype 1 – scenario 1

The second scenario takes place in an outdoor virtual environment which presents a low poly model of a ruined city street. The models are textured through projection mapping of archival photographs on building surface. The camera glides through the street while voice-over described how Warsaw was destroyed during the uprising.

Screen print of prototype 1 – scenario 2

Screen print of prototype 1 – scenario 2

Once the prototype was ready I did a quick round of user testing by showing the two scenarios (through google cardboard) to museum experts and friends. Most of them found the second scenario better than the first. This might seem surprising at first, since the first scenario is interactive which should translate to a more interesting user experience. However, on closely analysing the experience of watching the two scenarios I realized that the difference boiled down to two factors - the quality of the narrative and the novelty of the virtual environment. The first scenario encouraged viewer to interact with the virtual environment, but the story that emerged through interaction was less engaging than the one told without any interaction in second scenario. In case of the virtual environments, though the first scenario had more polished graphics, the indoor environment was less attractive than even the low poly ruined city look of scenario two. I understood the importance of location in crafting a powerful experience during this round of prototyping and testing. Instead of providing simply a backdrop where the story takes place, I felt the location - ruined city of Warsaw - needs to be a character in its own right. With these realizations, I started working on level design of the next version of the prototype.

Creating the second prototype

The updated version has only one scenario. The virtual environment is based on a real location in Warsaw that was identified from the eyewitness account. For this prototype, I tried to create a realistic virtual reconstruction of the chosen place. I researched the location thorough an initial visit to the site (rebuilt after the war) and afterwards by going through old maps, hundreds of archival photographs and hours of videos captured by insurgents during the uprising. Once I had sufficient image references, I started working on level design by following an iterative process that included:

sketching on paper

mapping and blocking in Unity

modelling in Blender

texturing in Substance Painter

assembling all assets in Unity

I made use of some high quality free 3D models from the asset store to reduce development time. Materials from museum archive like war sounds, photographs, digital scan of posters were extensively used to add realism to the virtual world. I tested each version of the prototype in Google Cardboard. After several redesigns, the prototype looked like this:

Though the virtual environment looked much better than in the first prototype, I was not fully satisfied with the design. Something was missing. Museum experts concurred with my opinion. One of my favourite aspects of this version is a slide show section where old photographs from the uprising are projected on a wall. In designing this segment, I had carefully constructed the environment (giant back wall of a building acting as projection surface, the rusted water tank in foreground emphasizing scale of the wall) <insert screen shot of the slide show> and camera movement (which starts levitating just before the slide show starts) to heighten the scale and the visual impact of projected images. What if instead of images video was displayed on building models, a kind of projection mapping in virtual environment? I started experimenting with video projection on 3D models in Unity. Results of those experiments looked promising which lead me to design next and final version of the prototype.

Creating the third prototype

The virtual environment was expanded to make greater space for the story to reveal itself. I decided to use video projection and additional audio elements to add layers to the story. My goal was creating a rich audio-visual narrative that would trace the outbreak of war (dramatically conveyed through audio recording of Hitler's declaration of war on Poland) and progress of the uprising (narrated through radio broadcast) culminating in the city’s destruction (narrated through the eyewitness account). In this way, the miniature narrative arc consisting of a beginning, a middle, and an end unfolds in the five-minute duration of the experience.

Museum experts loved the demo, commending on its ability of conjuring a highly authentic yet dream-like vision of ruined Warsaw. Currently the museum is seeking external funding for a creating a production version that can be exhibited at the museum.

What I learnt from this project

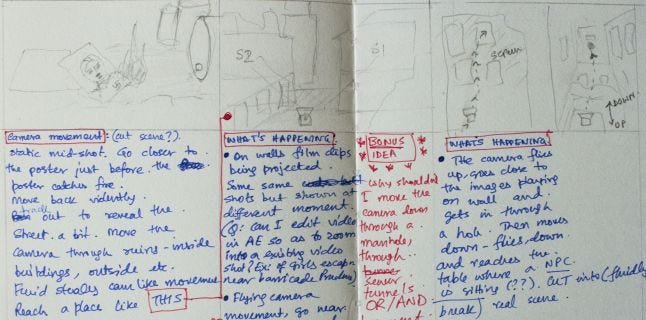

Before starting I had an inkling that designing for Virtual Reality would be very different from designing for screens. However, the magnitude of this difference only started to dawn upon me as I started prototyping in Unity. I think storyboarding is useful for VR design, but without prototyping in 3D, early design decisions are likey to fail. That is why it's crucial to include some form of VR prototyping right from the start. In my case, storyboarding became more useful from prototype 2 onwards, once the overall look and feel of the environment was clear to me.

Storyboard for prototype 3

The second thing I learnt is – audio is at least as important as visuals and it’s crucial that sound design is part of the process of world building from the start. I was working as a one-man team responsible for both the visuals and the audio. Hence working on both at the same time happened naturally. Most teams will have dedicated sound designer. It’s crucial to get her involved from project inception stage. I strongly feel that instead of thinking how spatial audio can be added to the finished environment, designers need to think how sound and visual design can be developed in synchronization. This brings me the most important aspect of sound design – audio in any form of VR experience needs to be spatial (be it CGI or live action, interactive or passive, real time rendered or 360 video capture). A significant challenge I faced was in deciding where to position the narrative voice in the 360-degree sonic environment. After some trials, I decided to place it close behind the viewer’s head, forty-five degrees up. I scripted the position of the sound source so that the viewer hears the voice speaking occasionally from the left, at others from the right. The shifts in position of sound source are synchronized to the shifts in narrative register.

After spending considerable amount of time designing an interactive narrative, I realized that interactivity does not need to be absolutely necessary for creating a compelling VR experience. An interactive story makes sense only if the interactions add something to the narrative experience. It’s an obvious fact which we can lose sight of in the heat of creating interesting mechanics, especially in a new medium like VR which presents novel forms of interaction. Truth be told, I had to think in terms of reduced or no interaction due to the inherent limitations of Google Cardboard (later when I used Oculus DK2 I did not have any external controllers). The crucial point to remember is (as noted by Breaking Fourth in an article on medium) – Even the most ‘passive’ VR experience will be more interactive than a traditional film, as the viewer has agency over which direction to look in. Two of the most acclaimed VR experiences from Oculus Studio – Henry and Dear Angelica contain few interactive elements, yet they immerse viewer into the story in a way that is possible only through VR. This is not to downplay the importance of interactive narratives whose potential can be seen in experiences like “Giant” and “6X9”. Rather, in my opinion the primary goal of VR storytelling should be striking a balance between narrative and sense of presence, through interaction and if need be without interaction.

(Witness is my first VR project. I’d love to hear what you think of it!)

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like