Atmosphere in Games - Part 7 - Realism in Games

Part 7 in a 10-part series about atmosphere in games - what it is, how to improve it, and how it breaks down into the various aspects of a game.

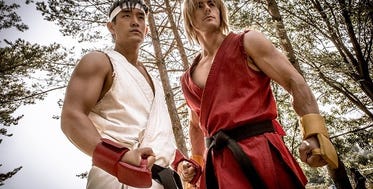

Ryulkane

Gameplay which contributes to a sense of atmosphere tends to involve realism - but not 'realism' in the way we tend to think of it regularly, but being real to the world in question. Magic in games is an example of something which isn't 'real' in the way we think about our world, but is real in the game. So, making the gameplay's relationship to magic understandable and earthy, we can increase the sense of in-game realism. On the other hand, the further you walk away from real-life realism, the more difficult it becomes to sustain a sense of atmosphere. Regardless of how comic or otherworldly the game is, retaining ties to real-life realism will always make the jokes funnier and the surreal surreal-er by giving some contrast. In this vein I've found that gameplay which is semi-realistic often helps ground a game and give it atmosphere.

Carrying 17 guns is not realistic unless all of them are small. Not that atmosphere was a strong point of the original Halo, but carrying only two guns at a time not only made the game feel a little more grounded, but it also created a unique gameplay element (for the time) around carefully choosing which weapons would get you through the next area the easiest. But, sometimes conversely, atmosphere in gameplay lends itself to simplicity. It's very difficult to get lost in a land of otherworldly adventure when you are constantly being distracted by annoying real-life gripes (examples: I need to pee, I haven't eaten for days, this loincloth is not in any way doing anything to make me warm, the amount of stuff I'm carrying means I can only move one centimeter at a time). Film, literature and TV also eschew these kinds of trivialities in the name of sustaining immersion.

The original Diablo did an incredible (though mixed) job of combining simplicity and groundedness in it's gameplay, which was probably via the influence of pen-and-paper role-playing games (remember those things?) more than any other particular consideration. It's approach to inventory management, killing things, hunting for items and swapping weapons - basic game mechanics - was fairly grounded and basic. If you wanted to look for something, you would either see it outright or scan the ground with your mouse pointer to see if you could find something. If you killed something, it stayed dead and it's corpse remained for the rest of the game. Swapping weapons took time, as it would in real life, as did inventory management. You could carry a lot of stuff, but not too much. But a lot of the annoying real-life mechanisms - the things which tend to bog down more meticulous role-playing games and reserve them for a niche crowd - were missing, meaning it was easier for a player to get immersed in the world, while still having a sense that it was 'real'(ish).

Now, as a point of interest, compare this to Diablo 2. There is no doubt that the gameplay of Diablo 2 was for the most part better, the graphics similar but improved, the same composer scoring the music- but for the most part the sense of atmosphere was just gone. Why was this? Because the gameplay didn't create better atmosphere, it created better gameplay. Inventory management - you could carry more, which removed some annoyances around with carting gear back and forth from the merchants, but the amount you could carry removed the game far from any real-life corollary. Similarly, switching weapons was instantaneous - no doubt more fun, but completely removed from real life. Monsters didn't stay dead in single-player, apparently to prepare the player for the multiplayer aspect of the game. In short, it moved far away from the role-playing end of the spectrum and more into the arcade end. I hear Diablo 3 is even further into this area.

Now, I'm not saying that for every game you must have a sense of realism, but a sense of groundedness and in-game contextual realism, in combination with a sense of simplicity to smooth over what could be a technical ordeal, will typically improve the atmosphere of a game - I think this is a balance, and you can definitely go too far here and start eroding fun. But my point is that it's not a question of fun-vs-realism - it's how those two things can be worked together to sustain atmosphere. And this also applies for the way the world itself progresses - but I'll tackle this in my next article.

Games which do this well:

Psychonauts (AAA, Payware): Although the world of psychonauts itself is quite bizarre, whimsical and cartooney, it never strays outside of that World. All of the action and behaviour is consistent with the world itself, and all additional game mechanics are well-thought-out and fit the context of the game immaculately.

Aquaria (indie, payware): The entire game fitted together smoothly. Although you were underwater, a kind of mermaid in a sense, the dynamics of movement and mechanics fitted te environment, the character, and her abilities and upbringing. It was a mesmerizing experience.

Games which don't:

Bulletstorm (AAA, payware): While expecting us to believe in a Serious, Hard, beautiful, realistic world where Serious things were happening and had immediate importance, we were also told that this arm-electro-chain melee thing made sense in the world context and that piloting a ten-ton robot dinosaur made sense in the world context. It wasn't fun to work out, it was fun to play, but it broke it's own atmosphere almost immediately.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)