Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Joseph Humfrey talks about how A Highland Song carefully crafts its story elements in order to make each playthrough feel unique to you.

The IGF (Independent Games Festival) aims to encourage innovation in game development and to recognize independent game developers advancing the medium. Every year, Game Developer sits down with the finalists for the IGF ahead of GDC to explore the themes, design decisions, and tools behind each entry. Game Developer and GDC are sibling organizations under Informa Tech.

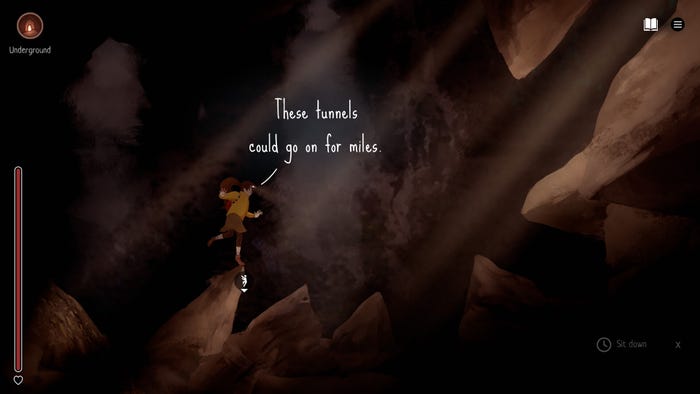

A Highland Song follows a teenage girl as she runs away through the Scottish Highlands, finding lost stories, hidden paths, music, and danger in the hills.

Game Developer sat down with Joseph Humfrey, director of the multi-award nominated title, to talk about the appeal of tying movement to the beat of music throughout the adventure, the challenges of creating a massive explorable place in 2D, and creating story elements that make it feel like each venture out into the highlands is your own unique journey.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing A Highland Song?

Hi! I’m Joseph Humfrey, co-founder of inkle and director on A Highland Song. I developed the concept behind the game, drawing on my experience in the Scottish Highlands as a child.

What's your background in making games?

I’ve basically been making games all my life! I played around with modding and simple programming as a child, and after studying Computer Science at university was fortunate enough to land a job at Rare. After spending 4 years there and 2 years at Sony’s now defunct Cambridge studio, I co-founded inkle alongside Jon Ingold, who has a background in interactive fiction and is a brilliant narrative designer.

I love all aspects of game development, whether programming, art, audio, or design. On the one side, that means I can fill in for any minor jobs in any discipline that need to get done (very handy at a small indie studio!), but on the other hand, it can sometimes mean I stretch myself too thin and am tempted to do jobs that would be better suited for a specialist with more experience.

Images via inkle Ltd

How did you come up with the concept for A Highland Song?

I grew up in Scotland and had a wonderful teacher (hi Mr. Brooks!) who used to take kids up into the Highlands to go walking and camping. He was extremely supportive and allowed us an unusual amount of freedom, especially given our age. That instilled in me a real love of the wild, rugged hills.

While exploring as a child, I used to dream up new ideas for games or levels, although none of them at the time related to Scotland. It wasn’t until I was older and had moved away from Scotland that I realized how much I missed it. That longing inspired me to create a game set there, almost as a way for me to return in spirit.

What development tools were used to build your game?

The game engine we used was Unity, although we built a bunch of custom tools for creating the 2d parallax layers of terrain, and a system for "splatting" them with thousands of decals in order to texture them. This system allowed us to texture in a dynamic level of detail, with smaller splats being placed in high detail on the paths where the player could walk, and larger splats filling in large areas of color and texture across the terrain.

And, of course, we used our narrative scripting language "ink" to build the narrative, dialogue, and script all the interactions. We’ve used ink in every single one of our games for the past 13 years, and we open sourced it back in 2016, so it’s free for anyone to use.

A Highland Song mixes music and exploration. What appealed to you about tying exploring the Scottish Highlands to the beat of the music?

Whether walking, running, or hiking, I find when you’re covering a long distance you start to feel your body entering a state of rhythm, both from your movement and your breathing. It's a kind of flow state, and especially after getting a second wind, it starts to feel timeless, like you could walk or run for hours.

The rhythm mechanics in A Highland Song are always tied into moments in the game where you’re crossing long distances, and we find it very fitting to have you jumping in time to music during these sections. The sense of momentum that comes with running and jumping in time to the music is designed to recreate that flow state that you can get in real life.

That’s the intent anyway. We hope it comes across!

The game’s store page states that the landscape forms itself around the shape of the music. Can you tell us what you mean by that, and how that affected the design of the environments players explore throughout the game?

The rhythm runs are used to cross smooth wide valleys between peaks, and we have a bunch of music tracks from the wonderful bands Talisk and Fourth Moon that are used for the rhythm mechanics in these sections.

The mechanic has been designed to be flexible—we can play any music in any of the sections, depending on the tone we want to convey. But because we want you to jump in time to the music, that means we need to dynamically place steps, rocks and gaps “just in time” off screen as the player approaches, timing it so that the exact time that the player needs to jump one of these obstacles matches perfectly with the beat of the music.

We did this by creating hundreds of patches of terrain, each of which corresponds to a rhythm pattern in a single bar of music. When a rhythm pattern is repeated, whether in a single piece of music or across different tracks, we can then reuse this piece of terrain. The terrain chunks are stretched and rotated together in perfect alignment following the valley floor, so that it matches the timing of the music.

Images via inkle Ltd.

What thoughts went into choosing the musicians who would create that audio backbone for the game? And how did you guide them in creating music that would shape the literal world under the player's feet?

Initially, we considered asking our composer to write music in the style of Scottish Folk, and although he has contributed wonderful tracks for the ambient exploration and narrative in the game, we realized we wouldn’t be able to beat the authenticity and energy of using real Scottish Folk music.

We approached Mohsen Amini, who is the leader of our absolute favorite band in the genre—Talisk. It turned out he is incredibly prolific, having started 3 separate folk bands. Not only that, he’s 100% independent like us, allowing us to negotiate directly without needing to talk to an intermediary. We licensed tracks from two of his bands—both Talisk and Fourth Moon.

The end effect is a soundtrack that is beyond our wildest dreams, combining original tracks from the incredibly talented Laurence Chapman who we work with regularly, as well as Talisk and Fourth Moon.

A Highland Song plays out in 2D, but is no less of a game of exploration despite this. What challenges went into that feeling of getting lost in a massive, sprawling land in two dimensions?

In A Highland Song, we aimed to craft a 2D exploration game that still captures the essence of wandering through vast, open landscapes. Our challenge was to merge the side-scrolling perspective with the feeling of depth and space, allowing players to climb a hill and overlook a 3D panorama of real places they could visit. That melding of 2D and 3D felt almost contradictory at first.

We experimented with slicing a 3D landscape into hundreds 2D playable sections, but ultimately chose a more hand-crafted approach. This method involves creating primarily 2D levels that layer up into the screen, offering a unique take where traditional parallax backgrounds become real playable destinations.

Thus, you can climb a mountain, take in the view, and, much like in Zelda: Breath of the Wild, fulfill the promise that if you can see it, you can go there. It’s a cliché, but we think it’s pretty cool that we did it in 2D!

However, in true open world games, you can mostly walk in a straight line in any direction which is partly where the sense of freedom comes from. By comparison, our 2D levels have hand placed places that link them together—you can think of them as portals or trapdoors between levels.

This creates a challenge—it’s not an open world that allows the player to strike out in any direction. However, this constraint allowed us to create a mechanic, filling the game with little map fragments that are clues to finding the paths between levels.

What thoughts went into the game's visual style? How did you create an incredible sense of depth and scope in the Highlands with your visuals?

At inkle, we often draw upon the aesthetics of traditionally animated 2D movies and comics, whether it’s Disney, Studio Ghibli, or even Tintin. Especially in the case of Ghibli, you see these lush hand-painted watercolor backgrounds that contrast beautifully with the cel-shaded characters and foreground elements.

We’ve also always loved digital painting pioneered by artists such as Craig Mullins and others, and always felt like it would be wonderful to use that digital painterly style an a literal way in game. And so, we approached Paul Scott Canavan, who is an incredible digital artist who is Scottish and has a love of Scottish landscapes and nature. We were delighted that he was keen to work with us!

Together, we developed the technique of building up hundreds of layers of splats or decals. Some are just a few simple painterly brushstrokes, some are entire rocky outcrops. Paul worked with our in-house illustrator Anastasia Wyatt to create a huge library of these pieces, allowing our level designer Nat Clayton to create entire vast landscapes from their work and have it all look hand-painted in a way that works at any scale.

The environmental lighting and weather effects were then critical for binding everything together, since the layering of fog, haze, clouds and sky are what creates a true sense of depth, distance, scale and space.

Images via inkle Ltd.

Survival is a vital part of the game as things can get dangerous in the highlands. Can you tell us how you developed the survival mechanics, and how you worked them around the specifics of the area you based the game in?

Early in development, survival mechanics were crucial—we aimed to portray the Scottish Highlands with authenticity, avoiding any overly quaint representations. While the Highlands are stunning, their beauty belies a potentially perilous wilderness. Despite the UK's modest size, it boasts extensive, unspoiled regions where it's easy to become disoriented and face danger.

However, we dialed back these survival elements later in development. Our goal was to balance the game's challenge with its narrative and sense of momentum. We wanted players to experience the impact of the weather and the rugged terrain, but without making the game excessively harsh, allowing the story and progress to remain at the forefront.

Your studio often explores story in intriguing ways. What thoughts went into creating a narrative in a game built around exploration? Into creating a story where players might not find every single path?

Although our studio is known for creating games with branching narratives, this branching structure is not one that we've really used in a long time. Ever since we made Heaven’s Vault, our narrative designer Jon Ingold has been working predominantly with a model that feels more like a database of story snippets. Each story snippet has a set of pre-conditions that look at what the player knows and the state of the world, and surfaces the most relevant content, whether that relates to an ongoing backstory or the character that they’re talking to right here, right now.

The net effect of using this technique is that the story feels entirely tailored to your own unique experience. Your particular route might cause you to bring a bottle of whiskey to a spelunker in a cave (which is an entirely optional thing you can do), and lead to the narrator telling you a little snippet about the history of whiskey smuggling in the Highlands a minute later.

I can recommend watching Jon Ingold’s talks on this subject, such as this one from GDC a few years ago.

What thoughts went into creating the various small stories the player could find along their journey? How did you make this place feel alive through the small, personal stories players could stumble across?

I feel I should let Jon Ingold answer this one for himself! This is what he said:

“One thing I was very aware of when sitting down to outline the story was that depictions of Scotland in media tend to be quite one-note. Everyone remembers Braveheart and William Wallace, but there’s not much Scottish history in films beyond that. Otherwise, it’s Brave, and Scotland as a mythological, magical place—in Highlander, similarly, despite the name Scotland, it is really just a "magic place"—a Narnia—that’s there to add some color.

So I wanted to make a structure that would allow us to put quite a wide range of real history in—we do mention Wallace, but we also touch on the Jacobites, the Romans, and of course the crofters and clearances who inhabited the Highland region for centuries before they became the empty wilderness they are now—while still allowing for a range of mythological elements as well without suggesting that Scotland "isn’t a real place" (Mythological stories are often depicted in fiction as more real than the people who invented and told the stories, which doesn’t make much sense).

And, ideally, we’d be able to tie this little stories back into the landscape directly so the player could connect the two sides of the game together—using stories to orient themselves and identify the hills, and that way understand where they were better. One thing I really like is when you hear players talking about their routes in the game, they do this—they’ll say “I took the cave below Luck’s Out and came out below the Forest Crown…” and the names have meaning because of their associated stories.”

You May Also Like