"Death in a Deathless System": Finding Solace through Empathic Interactivity within the Pokemon Series

An exploration of how the Pokemon series of video games creates a deathless system that enables individuals who have experienced permanent1 loss to find solace in an immortal virtual world through the emergent gameplay style of Nuzlocke.

Pokemon was the first game series I have ever played and now I believe that it will also be my last as I might still be playing it when I am much too old to even get out of bed. With the release of Pokemon Sun and Moon, the latest installation in the series as of 2016, the Pokemon series of video games shows no signs of waning as a franchise. In fact, the latest Pokemon Sun and Moon was reported to be “the most pre-ordered game at Gamestop in 2016” (ThisGenGaming, 2016) and it went up against American favorites such as Battlefield 1, and Call of Duty: Infinite Warfare. On the other side of the world, in Japan, the home market of Pokemon, the latest incarnation in the series managed to sell more than 1.9 million copies in the first three days of its release, putting it in the running to “become the fastest selling video game in history” (NowLoading, 2016). Given the “enormous investment that fans place in the franchise – economically, temporally and emotionally – and, more generally, the ‘activity’ that accompanies Pokémon consumption and engagement, it is possible to view the users of Pokémon as a ‘learning community’” (Bainbridge, 410) and because of that insight mixed with my experience of playing Pokemon since the original 1996 release, I wonder how many have come to learn that while Pokémon may be game made for entertainment, it still is able to impact our lives in many ways. Pokemon Sun and Moon marks the seventh generation of the video game series and in its 20 years as a franchise, I have lived more than a quarter of my average human lifespan, encountering the joys and struggles of life, but none have left as much as an impact on me as death and the feelings of permanent loss that come with it. Yet, in a direct contrast to real life, Pokémon exists in a virtual world where there is no death state and its feelings of loss are all but temporary, creating a deathless system that I believe can help others cope with the real cessation of life that is death. Through my experiences, I have come to view Pokémon not only as a game but as an environment that can provide the possibility for finding solace after loss through reconnecting with the finite nature of our human life cycle. Today, I will explore just how the Pokemon series of video games creates a deathless system that enables individuals who have experienced permanent[1] loss to find solace in an immortal virtual world through the emergent gameplay style of Nuzlocke, of which allows us to gradually come to terms with the continuity of our life by acknowledging the reality of death at our own volition.

Fig.1 - Digital Illustration of Pokemon Trainers interacting with Pokemon. Pokemon X and Y. The Pokemon Company. Nintendo. 2013

You cannot die in a Pokemon video game. Your user-created avatar, a Pokemon trainer (the human characters illustrated in Fig.1 above), will always remain in an ‘alive’ state throughout the game and never encounters a ‘death’ state. In similar fashion, your companions, your Pokemon (the creatures illustrated in Fig.1 above), do not experience death and when they are defeated in battle, they will only faint, rendering them unable to fight until they are healed with an item or taken to a Pokemon Center, a free hospital that cures all ailments for Pokemon (Fig.2 shown right).  If all your companions faint in an instance of battle, your avatar faints as well, blacking out, only to awaken in a Pokemon Center fully refreshed and healed. In this way, the system of Pokemon has a ‘lose’ state instead of a ‘death’ state, and there is a fine difference between both. In the list of bestselling video games[2], of which Pokemon is a part of, there exist a number of games (particularly action games of the shooter genre, that of which encompasses the likes of the Call of Duty series) which favor showcasing the literal death of the player on the screen (Fig.3a shown below). Even in similar popular child friendly games such as Lego Marvel Superheroes, your character will explode into Lego parts upon losing all their health (Fig.3b shown below), and it is this action of showcasing character ‘death’ as the ‘lose’ state that Pokemon opts to skip past, resulting in a deathless system. Pokemon has a deathless system even though it provides the agency to lose and fail, because its system does not posit loss and failure as death.

If all your companions faint in an instance of battle, your avatar faints as well, blacking out, only to awaken in a Pokemon Center fully refreshed and healed. In this way, the system of Pokemon has a ‘lose’ state instead of a ‘death’ state, and there is a fine difference between both. In the list of bestselling video games[2], of which Pokemon is a part of, there exist a number of games (particularly action games of the shooter genre, that of which encompasses the likes of the Call of Duty series) which favor showcasing the literal death of the player on the screen (Fig.3a shown below). Even in similar popular child friendly games such as Lego Marvel Superheroes, your character will explode into Lego parts upon losing all their health (Fig.3b shown below), and it is this action of showcasing character ‘death’ as the ‘lose’ state that Pokemon opts to skip past, resulting in a deathless system. Pokemon has a deathless system even though it provides the agency to lose and fail, because its system does not posit loss and failure as death.

Fig.3a (Left) - In-game screenshot of Killcam screen. Call of Duty 4. GameSpy. 2008. Fig.3b(Right) - In-game screenshot of Lego character explosion upon loss of health. Lego Marvel Superheroes. Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment. 2013.

For us humans, death represents the final moment of our biological human life cycle and when we cease to be, our life cycle ends. In remembrance of our dearly departed, we hold funeral rituals to honor the dead but also to help the living cope with the permanent loss of those dear to them. We might come to understand that “death may be ultimately incomprehensible. But if games are playgrounds for thought, they may be the perfect venue for testing our reactions to this unknowable thing.” (Grant, para.10) then we must be critical of the reactions that emerge from this testing. Video Games hold ‘funerals’, that act as reactions tests, for their characters as well, and in action shooters such as Counter-Strike: Global Offensive, we can see these presented as intermittent respawn screens (Fig.4 shown below) that either show the adversary that defeated you or the limp ragdoll body of your avatar. Yet, these “funerals”, these respawn screens, only last as long as it takes for your virtual character to revive, usually averaging out to less than thirty seconds, and thus do not present an ample moment for you, the player, to respect the value of the finality that death brings to our life cycle.

Fig.4 - In-game screenshot of player character (foreground) lying dead on the floor while their killer (middle) is shown being eliminated by the other members of the player’s team (lower right). Counter-Strike: Global Offensive. TheGamingWoodpecker. 2014.

Instead, this type of death and quick revival creates an environment that makes it “a prerequisite that the player's avatar has to 'die' many times in the process of unravelling the plot” (Mukherjee, 1) or in the case of action shooters, to unravel the skill needed to survive longer in battle. When Death is presented in this liminal way, and in a fashion similar to our human cessation of life, we learn via Bogost’s theory of Procedural Rhetoric, that death is a hurdle to success, and thus representative of failure and temporary loss. Procedural Rhetoric posits that “video games make claims about the world, which players can understand, evaluate, and deliberate” (Bogost, 119) and the procedure of the quickly repeated process of living and dying, playing and respawning, video games that have a ‘death’ state create a “reversibility [that] can be seen as something that trivializes the ‘sacred’ value of life” (Mukherjee, 1). In our reality, we cannot reverse death, but in the virtual fantasy of our video games, we are able to defy the natural human cycle of life by reviving quickly without the same feeling of permanent loss that is encountered in real life. Videos games may present a virtual fantasy, and in that perspective, these deaths may seem inconsequential but “fantasy pulls the study of videogames into the domain of everyday life, where the banal and the meaningful collide” (Goetz, 433) , thus we must consider that even in games, life holds “sacred” value because of the potential we have as humans to act upon our environment and ourselves when we are alive. If games can make claims about our world then “for all the chances games give us to experience and cause death, they very rarely give us the opportunity to process it in meaningful ways” (Grant, par. 10) to which points towards our inability to represent the weight of death in popular video games as we feel it in life. Reversing death and respawning in video games allow us to continue playing and that mechanic is not the problem, rather, it is the treatment of it that shallows the meaning of death. Action video games that have a ‘death’ state rarely handle the death of their virtual characters with the same reverence and thoughtful care that we humans provide to our own living brethren, for these death states center around the individual player, not the companions around them[4]. These types of video games remove the meaningfulness[5] of death in relation to our reality, through their inadequate handling of death by trivializing and normalizing it through quick repetition and revival, thereby failing to accurately represent the intention of death to teach us about the value of our human life. Thus, these types of video games cannot provide an ample source of solace for players who seek to cope with their experience of permanent loss of their own loved ones, their valued companions in real life. Pokemon however, with its deathless system, is enabled to provide solace for the player because it allows for an emergent gameplay style called Nuzlocke that affords the individual the complete independence in a safe space to decide how much they wish to face the notion of death as a part of our natural life cycle and when they would like to come to terms with it through the deletion of their valued Pokemon Companions.

Nuzlocke in the Pokemon Series is an emergent style of gameplay that was created by a player in 2012, of whom the style is titled after, and posits in summary that every Pokemon which faints in battle must be released. The Pokemon Series affords the opportunity for a Nuzlocke style of gameplay because of a mechanic known as Release which allows you to permanently release a captured Pokemon, your companion, to the wild, releasing the Pokemon of its bound duty to battle for you. This Release mechanic exists because there is a finite amount of space catered in the game to store all your Pokemon and a determined player might eventually fill up all the space, as such, the title of ‘Release’ is a dramatic element that hides its true nature of literally deleting data to clear up space. Yet, the Release is a mechanic that is rarely[6] used by the average player to clear up storage space as the latest incarnations of the Pokemon series allow every player to store up to 961 Pokemon per game, more than enough space for every Pokemon. As such, Release becomes a utility mechanic that solves a technical in-game problem, but yet, its function of deletion enables an emergent gameplay that makes use of both its dramatic and mechanical elements to create a hard, skill intensive play style that is Nuzlocke. The main story mode of Pokemon is not a skill intensive game and its easily understandable gameplay affords accessibility to players of all skill levels and ages. Players seeking a greater challenge in the main story of Pokemon have created the gameplay style of Nuzlocke because it removes the safety that is afforded by the deathless system in Pokemon by making use of its Release Mechanic to create a ‘death’ state. A player and their Pokemon companions can never ‘die’ and this affords the casual player the opportunity to learn from their loss and try again without the ultimate fear of a finite death that exists in our reality. In direct contrast, Nuzlocke allows for the notion that a player and their Pokemon can ‘die’ and this is all enforced by the player alone through the manual usage of Releasing the Pokemon after it is defeated in battle, resulting in the permanent deletion of your companion. Now, the manual process of Releasing a Pokemon (Fig.5 shown below) is a little tedious because you would have to find a Pokemon Center and from an in-game terminal within, open up the Storage window to which you would be able to highlight the Pokemon for Release.

Fig.5 - Photograph of the lower screen of a Nintendo 3DS Handheld console showing the highlighted pokemon (outlined in red right) and the menu screen (icons left) that has the RELEASE option. Pokemon HeartGold and SoulSilver. The Pokemon Company. Nintendo. 2009.

Upon highlighting the Pokemon, the game displays a sprite of the Pokemon companion, and if you choose to Release the Pokemon, the game asks you to confirm once more. If you accept, the Pokemon is “Released” and a narrative dialogue box describes the Pokemon leaving, yet in all respects, the Pokemon is deleted permanently. Throughout the manual process, there are no mechanical hurdles to stop you from Pokemon deletion as there is always a Pokemon Center that is easily accessible. The true hurdle, however, comes from the player themselves. The hardest part of the Nuzlocke gameplay style is that you are essentially deleting a companion that you spent the effort to catch, nickname, train, and then fight with, all of which creates an attachment to a virtual object that is akin to our human attachments we form over the course of our lives. In this hardship of the literal release of attachment, players have found a greater challenge in testing their skill in an attempt to keep their Pokemon companions from fainting and thus needing to be released as dictated by the player enforced style of gameplay. The playability of Pokemon allows for the Nuzlocke gameplay pattern to emerge through player agency, and “playability is a game’s key affordance of profound loss: the pain is not that you lose, the pain is that you must continue” (Harrer, 619) to which links towards the continuation of being able to play Pokemon without that specific companion, mirroring our experience of continuing life without our beloved human companions. The crux of the Nuzlocke style rests entirely on the onus of the player to conform to the emergent rules of play and release their Pokemon Companion, but there is nothing except the Player’s own consciousness to which to govern their actions. Nothing in the entire Pokemon series is going to force you to release a Pokemon except for yourself. At once, in the process of releasing a Pokemon, the player is confronted with the notion that they hold the power of death over a virtual companion, of which you have formed an attachment with, and is thus forced to contemplate the permanent loss of them. It is here in the contemplation of permanent deletion of a virtual companion, that an individual can find solace from death by facing the reality of it and deciding if they are ready to release in the form of acceptance and the letting go of attachment[7].

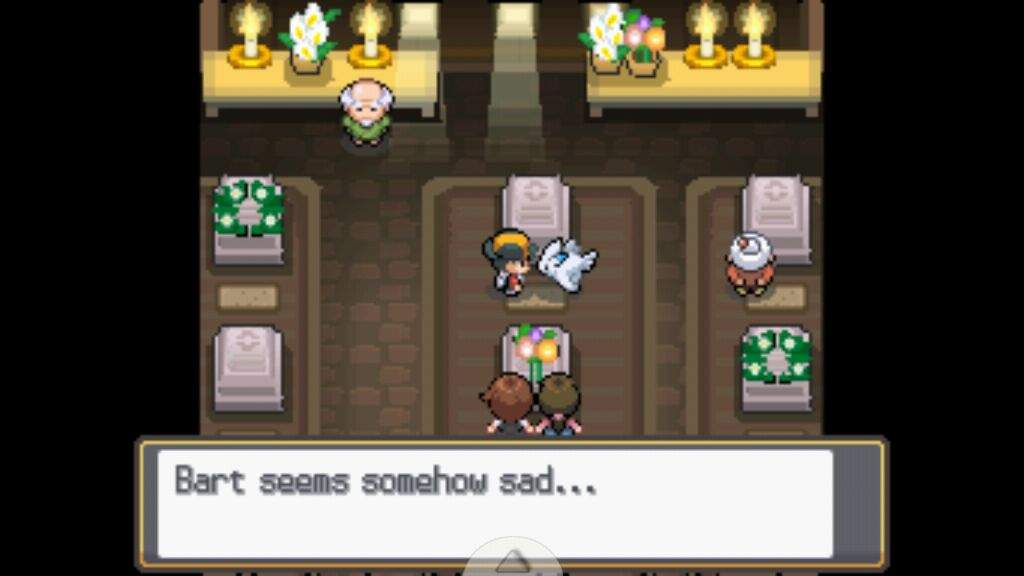

Pokemon does not have a mechanical option for death in its system, but it does allude to it narratively through descriptions of its Pokemon and of the world. For example, Lavender Town, a key story location in Pokemon’s Generation One to Four, has a building called “The House of Memories”[8] of which was built to hold the graves of countless Pokemon (Fig. 6 shown below).

Fig.6 - In-game screenshots of the “House of Memories” showing the graves of Pokemon and the reply from your Pokemon companion if you choose to read the inscriptions on the tombstone. Pokemon HeartGold and SoulSilver. The Pokemon Company. Nintendo. 2009.

In addition to locations that allude to a cycle of life and death in Pokemon, there are the description of Pokemon that plainly show that Pokemon acknowledges the passing of life. Take for example, Cubone (shown in Fig.7 right), of who is recorded in the Pokemon Moon with the description, “The skull it wears on its head is that of its dead mother. According to some, it will evolve when it comes to terms with the pain of her death” indicating that not only do Pokemon die but that they also have the self-awareness to acknowledge their own cycle of life and death, possibly hinting at the capability of empathy.  Through the use of such dramatic elements in form of narrative, Pokemon is able to ground its virtual fantasy world in the realm of reality even though it does not allow the player or their companions to actually die. Pokemon may be a series aimed towards the demographic of children but it treats the moment of death with respect and not solely as a game mechanic, meaning that Pokemon doesn’t force you to face death but rather allows you, the player, the agency to decide when you would want to acknowledge it. The narrative elements of Pokemon that allude to the cycle of life and death are there to remind you that while you may play the game in a deathless system where no in-game action or event will ever permanently result in the loss of yourself or that of your companions, the reality that you live in does. Thus, the emergent gameplay of Nuzlocke is able to further bolster the player’s agency to acknowledge the reality of death by allowing the player full control over their choice of Releasing their companions, to accept their permanent deletion, to which mirrors our own process of release from grief brought about by death. Pokemon as a Video Game allows us to find solace through process and emergent gameplay but it is only able to achieve this because it treats its virtual Pokemon creatures with a respect that is on par with how we treat our own human companions, a treatment that Game Developers can learn from to create greater interactivity for players.

Through the use of such dramatic elements in form of narrative, Pokemon is able to ground its virtual fantasy world in the realm of reality even though it does not allow the player or their companions to actually die. Pokemon may be a series aimed towards the demographic of children but it treats the moment of death with respect and not solely as a game mechanic, meaning that Pokemon doesn’t force you to face death but rather allows you, the player, the agency to decide when you would want to acknowledge it. The narrative elements of Pokemon that allude to the cycle of life and death are there to remind you that while you may play the game in a deathless system where no in-game action or event will ever permanently result in the loss of yourself or that of your companions, the reality that you live in does. Thus, the emergent gameplay of Nuzlocke is able to further bolster the player’s agency to acknowledge the reality of death by allowing the player full control over their choice of Releasing their companions, to accept their permanent deletion, to which mirrors our own process of release from grief brought about by death. Pokemon as a Video Game allows us to find solace through process and emergent gameplay but it is only able to achieve this because it treats its virtual Pokemon creatures with a respect that is on par with how we treat our own human companions, a treatment that Game Developers can learn from to create greater interactivity for players.

In Pokemon, the Pokemon creatures that you capture and ultimately come to befriend, are not only just tools to be used but also friends you play and live with. The latest incarnations of Pokemon increasingly offer a suite of alternative engagements with Pokemon rather than the iconic battling of them. In the latest Pokemon Sun and Moon, the most accessible form of engagement is one of utilizing the Pokemon Refresh screen (Fig.8, shown below) to foster friendship with you Pokemon as well as to provide the mechanical ability to heal them from negative status effects such as poison.

Fig.8 - In-game screenshots of Pokemon Refresh being used with the Pokemon Eevee. Note the human-esque expression of fatigue (left) changing into elation (right)and the heart symbols. Pokemon Sun and Moon. The Pokemon Company. Nintendo. 2016.

In Pokemon Refresh, you interact with the Pokemon via the stylus or with your finger using gestures such as petting and rubbing in circles, and it is this familiar motion that allows you to connect to Pokemon even though it exists within the screen. Further game mechanics  such as feeding your Pokemon (Fig.9 shown right) with a variety of non-battle related consumables to evolving them via other methods such as achieving maximum friendship allow the player to realize the value of Pokemon Creatures beyond just simple tools for battle and for clearing challenges. These interactivity with Pokemon, virtual creatures, allow us as players to empathize with them and become cognizant of the fact that while we may logically categorize these virtual beings as “not human”, our emotional being allows us to connect with them on an emotional human basis, to which we are able to choose to recognize them as on par with being “human”. It is this Emphatic Interactivity that Nuzlocke takes advantage of to allow us as player to experience the feelings of death and permanent loss. Yet, we must be cognizant that not every player is able to form attachments because “attachment formation to virtual products is heavily and simultaneously influenced by attributes and emotions associated with individuals’ existence in real as well virtual environments.” (Nagy, 1131). For players, Emphatic Interactivity is a concept that affords players a heightened engagement with the virtual environment by utilizing our emotional ability of empathy, that of which is the capacity to understand and feel the experiences of another person, in this case Pokemon, so as to enable players to act on their human emotive impulses, in essence, allowing them to be non-violently human. Allowing players to act in a emphatic human manner during gameplay is how Pokemon enables the player to acknowledge the reality of death at their volition. This acknowledgement allows the player to reconnect back to the natural cycle of life and death, thereby providing a sense of ending, of fulfillment and solace, rather than allowing them to deny it or to trivialize it, to which there is no sense of end, no fulfillment or solace for the permanent loss that a player feels. For Game Developers, Emphatic Interactivity promises not only a greater user engagement but also the generation of emotive depth that allows a game to go beyond existing as mere entertainment, enabling the player to learn to be more emphatic with virtual objects through Procedural Rhetoric. Through the process of emotionally connecting and understanding virtual objects, such as Pokemon, we will be able to utilize the interactiveness of the video game medium to not only deploy better entertainment but to also allow the users to reflect upon the way in which they connect and understand others, thus furthering our ability to then relate to the environment around us, and in essence making us more cognizant of the empathy that we employ in our daily life. If we can learn to better our empathy, than I believe that we can find more solace, more comfort, in the chaotic and mysterious nature of our lives.

such as feeding your Pokemon (Fig.9 shown right) with a variety of non-battle related consumables to evolving them via other methods such as achieving maximum friendship allow the player to realize the value of Pokemon Creatures beyond just simple tools for battle and for clearing challenges. These interactivity with Pokemon, virtual creatures, allow us as players to empathize with them and become cognizant of the fact that while we may logically categorize these virtual beings as “not human”, our emotional being allows us to connect with them on an emotional human basis, to which we are able to choose to recognize them as on par with being “human”. It is this Emphatic Interactivity that Nuzlocke takes advantage of to allow us as player to experience the feelings of death and permanent loss. Yet, we must be cognizant that not every player is able to form attachments because “attachment formation to virtual products is heavily and simultaneously influenced by attributes and emotions associated with individuals’ existence in real as well virtual environments.” (Nagy, 1131). For players, Emphatic Interactivity is a concept that affords players a heightened engagement with the virtual environment by utilizing our emotional ability of empathy, that of which is the capacity to understand and feel the experiences of another person, in this case Pokemon, so as to enable players to act on their human emotive impulses, in essence, allowing them to be non-violently human. Allowing players to act in a emphatic human manner during gameplay is how Pokemon enables the player to acknowledge the reality of death at their volition. This acknowledgement allows the player to reconnect back to the natural cycle of life and death, thereby providing a sense of ending, of fulfillment and solace, rather than allowing them to deny it or to trivialize it, to which there is no sense of end, no fulfillment or solace for the permanent loss that a player feels. For Game Developers, Emphatic Interactivity promises not only a greater user engagement but also the generation of emotive depth that allows a game to go beyond existing as mere entertainment, enabling the player to learn to be more emphatic with virtual objects through Procedural Rhetoric. Through the process of emotionally connecting and understanding virtual objects, such as Pokemon, we will be able to utilize the interactiveness of the video game medium to not only deploy better entertainment but to also allow the users to reflect upon the way in which they connect and understand others, thus furthering our ability to then relate to the environment around us, and in essence making us more cognizant of the empathy that we employ in our daily life. If we can learn to better our empathy, than I believe that we can find more solace, more comfort, in the chaotic and mysterious nature of our lives.

Pokemon is a game series that allows you and I to continuously act with our human emotions and through that, allows us to deploy the experiences of permanent loss from our reality into a deathless virtual world through which we are able to explore the depths of our own experiences through Empathic Interactivity with virtual creatures. The value of these creatures is imparted upon us through a process of gameplay and its Procedural Rhetoric, to which we learn that these creatures are akin to the value of human companions, and thus are able to reconcile our experiences via the choice of utilizing the emergent gameplay style of Nuzlocke to release Pokemon companions. In this process, we are able to come to terms with the feelings of permanent loss that come with Death at our own volition, thus affording us the ability to attain solace through the acknowledgment and understanding of our natural cycle of life and death. Yet, for us to achieve this solace, we must consider that playing games and the act of play itself is a part of our human learning process. As Bogost puts it, “play refers to the “possibility space” created by constraints of all kinds. Play activities are not rooted in one social practice, but in many social and material practices” (Bogost, 121), and thus play allows the possibility to to learn if we are willing to learn. Our own conscious willingness is what drives us to live our lives, and so after learning just how Pokemon, a video game, can help us to better find solace, would you be willing to explore video games as more than just a medium of entertainment and become aware of its abilities to further aid you in life?

Footnotes

[1] I have written permanent loss as a way to be specific about the type of loss and yet not explicitly state death as there are many other forms of loss.

[2] The list of best-selling video games is a list that is curated by Wikipedia and while the site offers proper citations for every figure, the open-source nature of the website must be taken into consideration. The list is, however, a useful quick reference for determining the highest sales for video games, rather than having to keep track of it through numerous individual reports.

[3] Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (CS:GO) and the action shooter genre was chosen as their respawn screens best illustrate how we portray player character death in video games. Other genres have their own representations.

[4] This is an important distinction as while we can come to understand and cope with the ultimate inevitability of our own death, it is much harder to understand the death of others, especially our loved ones, to which we hold attachment to.

[5] To further clarify, I use the word “meaningfulness” here to represent the intention of death to teach us value, that of which is related to our life and our reason to exist.

[6] It is of note that competitive players and pokemon “breeders” employ frequent use of the release mechanic to clear storage space as these players are constantly found breeding new Pokemon in the hopes of attaining Pokemon with better stats or a rare move, so as to gain an upper hand in competitive play. The ethics of this competitive breeding and the values it reflects on our culture can be discussed in another paper.

[7] It is important that I address that the “letting go of attachment” does not mean forgetting the deceased. It is a human process to which we can arrive at the final stage of acceptance after experiencing grief or tragic loss. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, M.D. (1969) On Death and Dying. New York: Macmillian, p. 45-60

[8] Previously known as “The Pokemon Tower” in the Generation One (Red and Blue) and Three (FireRed and Leaf Green). The

Works Cited

Bainbridge, Jason. “‘It is a Pokémon world’: The Pokémon franchise and the environment”. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 2014, Vol. 17(4) 399-414.

Bogost, Ian. “‘The Rhetoric of Video Games.’ The Ecology of Games: Connecting Youth, Games, and Learning”. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008. 117–140.

Goetz, Christopher. “Tether and Accretions: Fantasy as Form in Videogames”. Games and Culture, 2012, Vol.7(6): 419-440.

Grant, J. P. “Life After Death”, Kill Screen Daily, 29 July 2011. Web <www.killscreendaily.com/articles/life-after-death>;.

Harrer, Sabine. “From Losing to Loss: Exploring the Expressive Capacities of Videogames Beyond Death as Failure”. Culture Unbound, 2013, Volume 5: 607–620.

Mukherjee, Souvik. “‘Remembering How You Died’: Memory, Death and Temporality in Videogames”. Digital Games Research Association (DiGRA). 2009.

Nagy, Peter, and Bernadett Koles. “‘My Avatar and Her Beloved Possession’: Characteristics of Attachment to Virtual Objects”. Psychology and Marketing, 2014, Vol. 31(12): 1122–1135.

NowLoading. “Pokémon Sun & Moon's Three-Day Sales Numbers Make It One Of The Fastest Selling Games In History”. NowLoading. 23 November 2016. Web <https://nowloading.co/p/pokemon-sun-moon-sales-japan/4151930>

ThisGenGaming. “Pokemon Sun & Moon ‘Most Pre-Ordered Game In 5 Years’, Call Of Duty Infinite Warfare Underperformed Says Gamestop”. 23 November 2016. Web <http://thisgengaming.com/2016/11/23/pokemon-sun-moon-most-pre-ordered-game-in-5-years-call-of-duty-infinite-warfare-underpreformed-says-gamestop/>

This essay was written as the Final Research Paper for University of Southern California (USC)'s CTIN190 course "Introduction to Interactive Entertainment". Fall 2016. Written 28 November 2016. Submitted 29 November 2016.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like