Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

"Action, Death, and Catharsis: Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare," from SHOOTER

A sample chapter from Reid McCarter and Patrick Lindsey's SHOOTER, an eBook collection of critical essays about games with guns.

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

[The following is a sample chapter from SHOOTER, a collection of critical essays about games with guns.

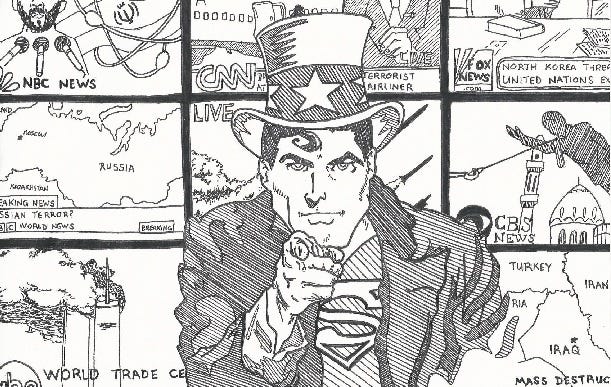

The anthology is co-edited by Reid McCarter (the author of this post) and Patrick Lindsey. It includes work from a variety of game critics, a foreword by Far Cry 2 Lead Designer Clint Hocking, and accompanying, hand-drawn illustrations.

SHOOTER is available for purchase at shooterbook.com or through Amazon.]

“Violence is never just abstract violence. It’s a kind of brutal intervention [of] the real to cover up a certain impotence concerning…cognitive mapping. You lack a clear picture of what’s going on…where [we are.]”

—Slavoj Žižek, from The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology

It’s 2007. George W. Bush is still the president of the United States. Tony Blair has just been succeeded by Gordon Brown as the British prime minister. Stephen Harper is now sitting in Ottawa, blatantly licking the boots of his southern neighbours at every opportunity. The Iraq War is around its halfway point (for the Coalition forces at least) and it has become abundantly clear that there will be no easy exit—no simple resolution where the nation is left with a stable government, subdued insurgency, and the level of sustained peace necessary for rebuilding itself. Come the spring, Russia will stamp on Georgia once more and the world will watch with a sort of bemused concern as Vladimir Putin steps aside to allow Dmitry Medvedev to provide a short, puppet-stringed intermission to his long-running presidency.

Throughout all of this, the West maintains an omnipresent fear of terrorism. It seeps from our cultural pores like hangover sweat. Every electricity brownout is the prelude to a possible invasion; any metropolitan shooting spree the potential catalyst for a new war. Attacks on our soil seem imminent, inevitable. The new century is still young, but it’s already apparent that the balance of power is shifting. Nations, religions, and cultures that served as footnotes to Western observers of 20th century global politics are becoming incredibly important. The international balance of power sees the old foundation that props up Western European and North American dominance developing cracks and faults. All of a sudden, the violence of war is filling the collective headspace of a culture that had been able to spend decades considering it “someone else’s” problem. It’s a serious preoccupation, war.

Could any videogame capture the spirit of these times better than Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare?

***

Call of Duty started off as a series of videogames about World War II. The narrative of that period is simple enough: a group of good guys fight to snuff out villains played by militant fascists hell-bent on global domination. On one side is freedom and democracy; on the other is genocide and dictatorship. The reality of this black-and-white dichotomy obviously breaks down in a number of ways when closely examined, but, for the most part, the popular reading of WWII encourages simplistic depictions. Call of Duty’s American developer Infinity Ward benefited from this clear “us versus them” understanding of WWII’s European theatre like many other first-person shooter creators before it. Without thinking much about the amount of violence they’re inflicting on real people, Call of Duty’s players could enjoy interacting with the battles of the Second World War as part of a dramatic portrait of the unending fight between good and evil. Though there were moments showing Allied ineptitude or cruelty—especially within the game's Soviet campaign, which opens with a quote from Stalin’s infamous Order No. 227 authorizing the execution of fleeing Soviet troops—the debut game in the now-famous series was mostly concerned with celebrating the historic heroics of its American, British, and Russian soldiers.

In 2003, when the first Call of Duty was released, it was still possible for Western audiences to get satisfaction from this kind of story. Stepping into the boots of one of the game’s protagonists, the player was made to feel like a participant in the defeat of Nazism—a cog in the great wheel of humanitarian progress. By the time Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare was in development the binary view of World War II explored in past games no longer felt important. The upsetting of Western power—unquestioned for decades—had begun in earnest. The wars of 2007 weren’t being waged against villainous armies, but insurgent groups fighting for reasons more complex than national interest or blind patriotism. To remain vital the subject matter had to change and tackle the conflicts weighing most heavily on Western minds.

***

Modern Warfare opens by explaining that Russia is embroiled in a civil war fought between a powerful ultranationalist group and government loyalists. Elsewhere, in an unnamed Middle Eastern nation (which prominently features a dictator’s statue holding an AK-47 aloft in an extremely familiar Baghdadian pose), ultranationalist-backed militants have overthrown their government, enraged by its Western sympathies. Thrown into this volatile mix are the game’s antagonists’ nuclear missiles, soon to be aimed at America’s eastern seaboard. After the Middle Eastern coup the Americans launch an invasion and the player takes on the role of Sgt. Paul Jackson of the Marine Corps’ 1st Force Recon Company. Concurrent missions give players control over Sgt. “Soap” MacTavish, a recent recruit with the British SAS who sneaks around Russia and Azerbaijan with a small special forces team, collecting intelligence on the ultranationalists’ plans. As the story follows the Marines’ attempts to capture the militants’ leader and the SAS’s covert actions, Modern Warfare moves through scenarios pulled from the Iraq War and what we imagine must sometimes occur as Western spies work behind enemy lines. The player, as Jackson, mans a Cobra helicopter’s machine gun as the Americans sweep into a fictional Middle Eastern city; they control him as squads of Marines work their way through urban streets, dodging RPG fire and bullets. As Soap, missions involve gathering information on nuclear weapons by sneaking onto freighter ships, extracting informants from within heavily guarded ultranationalist camps, and sabotaging enemy plans.

Throughout the game—and most explicitly in levels set in the Middle East—Western players are given the chance to participate in the kind of wars they’ve been following in the news, discussing with friends, and worrying about throughout recent history. The characters of Jackson and Soap, the game’s first-person view forcing audiences to see through their eyes, are notably faceless and voiceless. They are a tabula rasa for Western players to project themselves onto. The collective preoccupations of the 21st century West—insecurity in the face of unstable Middle Eastern nations and the reawakening of the Russian bear—are made both dramatic and interactive in Modern Warfare. Through the lens of an easily palatable action script, the audience is given the ability to take an active part in the anxieties lying beneath everyday modern life. Instead of sitting around feeling powerless by the complex changes of shifting international power balances, we’re given guns, recharging health bars, and license to kill moving targets dressed up as our greatest fears. The entire game is a large-scale exercise in catharsis. (Modern Warfare, by the rules of dramatic escalation, would have to one-up itself by bringing the foreign threat to Western soil in its sequels. Washington, London, and Berlin would all become warzones once more.) It’s a therapist’s couch where the subconscious of a culture is drawn to the surface and dealt with out in the open by way of intense, virtual acts of violence.

***

This effect is furthered by the fact that there’s no such thing as proper death in Modern Warfare—nothing to inspire real fear in the face of overwhelming danger. The player character may slump to the ground, screen covered in the dripping gore the game uses to indicate wounds, but it’s not permanent. Death is an inconvenience at most. It’s a minor setback on the path to glory. Wait a second or two and mistakes are erased, the grave cheated long enough to turn things around and get the mission back on track. War, for Modern Warfare’s developer and audience, is a grand action film—one in which the camera winces away from the ugly effects of violence in favour of its more exciting aspects. We’re interested in explosions, yes—absolutely, yes—but the distasteful corpses they create are almost never given second thought.

It’s for reasons like this that the power fantasy presented in Modern Warfare is such a potent one: You go to war to protect the free world, but, regardless of the incredible risks you take, you cannot die—with one notable exception. For most of the game the player, participating in the world through a first-person viewpoint, is able to shrug off sprays of bullets and grenade shrapnel by hunkering down and waiting for their health to restore itself. Even a fatal wound results in a quick respawn that sets the action back only a handful of minutes. The only time when this isn’t the case is in what is probably Modern’s Warfare’s most memorable sequence: the sudden detonation of a nuclear bomb during a mission to rescue a downed Cobra pilot, and Sgt. Jackson’s subsequent (slow, terrifying, seemingly agonizing) death. We hear Jackson’s labored breathing, the sound of his heart pumping, the eerie whistle of an atomic wind. A dread mushroom cloud blooms over the ruined cityscape’s horizon. These minutes are apocalyptic, and deeply disturbing.

It may seem puzzling, in a game characterized by its ability to make Western players feel invulnerable in their fight against collective foreign terror, that this death occurs so graphically. Jackson is an American soldier, after all, and he is fighting to stop the forces attacking the stability of our civilization. But his brutal last moments make sense as an effective way of increasing the stakes of the conflict. They give the player even more reason to justify their fears of the foreign threat and validate the basic villainy of the opposing nations haunting our society’s dreams. Sgt. Jackson is a sacrificial lamb, and the subversion of the game’s usual immortality mechanics are used to underline how proper it is for us to fight.

Much like the section of Modern Warfare that throws players 15 years into the past—where two British snipers traverse the irradiated ghost town of Pripyat, Ukraine (abandoned after the infamous Chernobyl meltdown)—the realization of a nuclear threat is meant to reinforce the stakes at hand. The enemy, both Russian and Middle Eastern, is ruthless, the game says. If they aren’t stopped our cities will look like Pripyat and our people will face the same miserable end as the dying Jackson. In the explosion of a Middle Eastern nuclear weapon (within a setting deliberately rendered as a fictionalized Iraq), Modern Warfare also offers a cynical realization of the real-world’s American/British rationale for invasion—those apparently very well-hidden WMDs. Of course our fears are grounded. Our willingness to fight foreign wars isn’t based on political self-interest, xenophobia, or a reassertion of cultural dominance: It’s what’s necessary to stop the enemy from using the immensely destructive weapons we know they have and want to unleash on us.

***

Despite the dramatics of these doomsday sequences, it’s important to note that Modern Warfare doesn’t end with Jackson’s death (as haunting a conclusion as that would be). The player simply jumps into Soap’s body and gets back to thwarting the enemy from another perspective, now even further bolstered by the tragedy of an intimately detailed loss. The ghastly violence of even the most powerful moments of the game are rendered inconsequential outside of their narrative power and reinforcement of the game’s central power fantasy. The player loses very little and soldiers on, returning to the usual rhythm of superheroic firefights and consequence-free player deaths. The mission progresses. The bastards will give way as long as we keep hammering at them.

The incredible success of a videogame of this sort speaks to the widespread frustration, on the part of the Western world, of trying to maintain control in a world that is becoming unknowable to us—a world that is actively defying the old colonial order that has shaped so much of our recent past. Revolutions (whether nationalist, militant, or religious) in Russia and the Middle East destabilize not just international relations and our own sense of safety, but any reassuring illusion that our way of life can continue for generations to come. We so deeply fear the continuing decline of the Western order—the erosion of systems like capitalism and democracy we feel to be intrinsically, universally correct—that we must find an outlet for these anxieties. Violence, directed at the nameless, faceless cause of these fears, is the natural response. But, obviously, not all of us want to pick up arms and fight on behalf of our nations (or, even more frighteningly, join up with foreign rebel groups or mercenaries). What Modern Warfare offers is a sense of contribution through a virtual world, free of real-world consequence. We can lash out—endlessly, violently—at threats without understanding them simply by picking up a controller. There’s no need to involve ourselves physically. Instead, we can purge our demons through an interactive manifestation of our largest cultural fears. And the best part? Inside the game we always get to win.

Its encouragement of cultural arrogance and a head-in-the-sand approach to international relations makes Modern Warfare an unhealthy form of catharsis in the long term. But its creation and subsequent massive commercial success are completely clear. It made sense that it would emerge from the roiling soup of 2007’s Western zeitgeist, and it also makes sense that it resounds even today, when the fallout of the last decade’s wars have birthed ever more destabilizing phenomena like ISIS, the annexation of Eastern Ukraine, and the ongoing revolutionary process of the Arab Spring. To properly grapple with our place in this increasingly tumultuous world, the West is going to have to provide work more complex than Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare. Fantasies of righteous wars and immortal soldiers aren’t going to be enough as we move forward. The violence, the mess, and the complicated narratives of 21st century conflict will require something that challenges audiences on a deeper level. To make a game that deserves to be called Modern Warfare, our deepest cultural insecurities have to be brought to the surface and painfully acknowledged, not affirmed and reassured.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)