Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Toward a Productive Games Discourse

The discourse about video games is shaped by varying degrees of "game literacy". In private conversations this is of course fine. But when it actually comes to pushing the craft forward, we should care about talking to (and not past) each other more.

"That's just my opinion!" This sentence or a variant of it is often put up as a kind of protective shield for people's statements and arguments when talking about games. Of course this phenomenon can be observed in other forms of media as well. At first sight, the critical discourse about art and entertainment is primarily concerned with the audience's personal opinions. However, given the youth of the professional industry and its still fairly underdeveloped theoretical foundation, the "opinion safety factor" is especially high when it comes to video games.

On top of that this state is quite regularly praised as something positive: "How great that there are so many different opinions! Otherwise it would be boring!" On the one hand this attitude is totally fine. In private, where self-portrayal, personal experience and emotional preferences reign, there might as well be an infinite number of perspectives. But when it comes to serious discussion, i.e. justifying and defending arguments, mere opinion will not suffice. If we want to talk to and not past each other, some common ground has to be established. Otherwise there is no reason for designers, developers, critics or gamers to argue in the first place.

Undeniable Differences

So, what can we do? After all, who is more and who is less right if not everyone can be at the same time? Eventually we will have to develop specific and complex criteria at this point (e.g. for strategy games), and we should certainly have a lot of discussions about those at another point.

But as a first step, it is very important to objectify the perspective on games in general to an extent. Of course this should not happen by distancing oneself from making any judgmental claims at all. Instead we should rather establish a common way of thinking about the medium. In the end this is what will lead to useful results that push the entire games discourse forward.

Now, when trying to assess games by the amount of "value" they provide for their players across their lifecycle, we immediately notice that this is an entirely subjective model. Not even looking at biasing factors such as taste, nostalgia and so on, the personal gaming history of the respective players will lead to dramatic changes in their evaluation. For example, a child might be fascinated by simply being able to move stuff around willingly on a screen. On the other hand, experienced RPG veterans will often simply shrug off even the most elaborate modern open world titles.

Now, when trying to assess games by the amount of "value" they provide for their players across their lifecycle, we immediately notice that this is an entirely subjective model. Not even looking at biasing factors such as taste, nostalgia and so on, the personal gaming history of the respective players will lead to dramatic changes in their evaluation. For example, a child might be fascinated by simply being able to move stuff around willingly on a screen. On the other hand, experienced RPG veterans will often simply shrug off even the most elaborate modern open world titles.

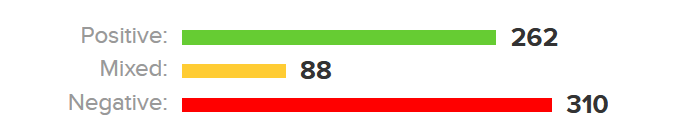

In internet forums, it is regularly possible to encounter such diametrically opposed points of view next to each other as well. The latest entry in some famous AAA series will be judged by one user as: "Incredibly fun! Brilliant flow! I have nothing to criticize!" Just a couple of posts later another user will respond: "Shallow gameplay, bland storytelling, technical issues, I rate it 4/10!" The problem is that they are both right from their very own perspective. Therefore, if we actually care about making progress, we need to look at their differences in detail.

The Spectrum of Game Literacy

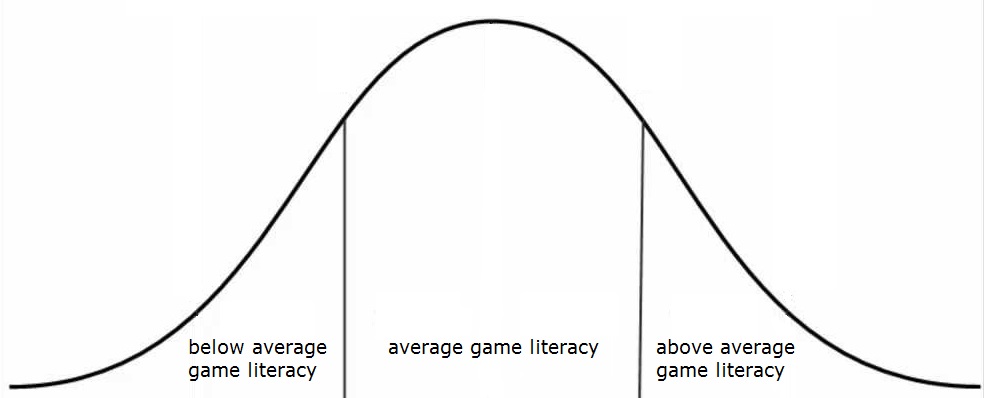

To shift the focus away from personal gaming backgrounds, we need to establish an imaginary third party in the discussion that functions as a judge. Now we need to position this judge somewhere along the spectrum implied above, i.e. somewhere between "Games? Huh!?" and "Dr. Ludo - games  expert". Besides the two extremes, a third reasonable starting point can be found in the middle, i.e. in the average game literacy.

expert". Besides the two extremes, a third reasonable starting point can be found in the middle, i.e. in the average game literacy.

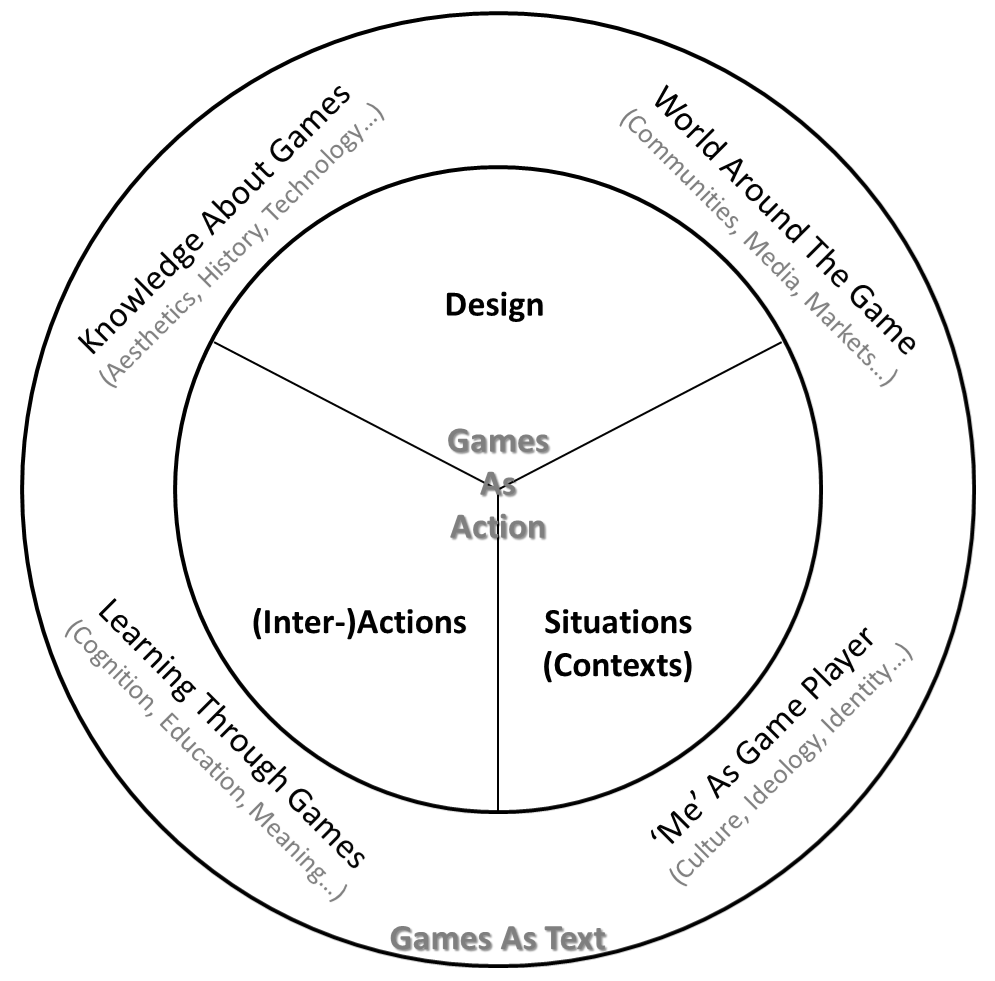

The concept of game literacy (incidentally a recent topic of the video series Extra Credits) does not just incorporate "player skill", but also more high-level abilities to analyze and classify games in the context of their sociocultural environment. Those are also a regular topic of academic discourse surrounding communication, education and learning in the landscape of modern media. Among others, Tom Apperley and Caterhine Beavis have tried to establish "A Model for Critical Games Literacy" (2013).

Objectification 1: The Clueless

Now, for a start let's take a look at the uninformed judge. His view on games is very innocent. He does not know genres and their conventions, and he is also not oversaturated from experiencing the same core mechanisms year after year. In a way this judge is reminiscent of Conan O'Brien's role of the "Clueless Gamer". He keeps asking basic, but reasonable questions regarding everything he encounters in a game: "What's the point? Is that interesting? Is this a worthwhile usage of my time? Why am I supposed to find 35 more pine cones and 15 pebbles now?"

This is the advantage of the "gaming illiterate": A mind free from decades of video game brainwashing, not having gotten used to all the weird idiosyncrasies of the medium. However this of course comes with the issue of significantly reduced competence. This judge is not able to classify a game or recognize improvements compared to similar titles. He will have to discover the core fascination of interactive entertainment again and again without establishing consistent language or making any really profound statements.

"Are we literally pushing a car through a desert? Why is this a game?"

So, even if looking through the glasses of cluelessness can help finding the forest for the trees once in a while, discussions with the unknowing judge will in practice not lead too far or deep. That is not only true from the point of view of critics, designers and other experts, but also for any layman somewhat involved in the gaming hobby as a whole.

Objectification 2: The Average

Let us therefore gear up. Our second judge is more or less the average gamer. He exhibits mediocre knowledge regarding games. He does know all the genres more or less, but not enough to be fed up with any of them. The majority of the industry creates their products around this stereotype, whose profile can serve quite well to make predictions about what many potential players may currently like.

On top of that many critics are using the same evaluation basis these days. Even though many of them would theoretically have access to a deeper expertise, they find themselves forced to maximize clicks and tell the masses what they want to hear. Most game ratings these days, and especially those of big platforms and magazines, are basically predictions about which games might be successful on the market.

The majority of people fall under the average game literacy.

At this point the disadvantages of this approach become quite apparent. Of course we can discuss game mechanics, the market and broader trends in the evolution of the medium with our average judge quite well. But will he be ready to break into uncharted territory? Probably not. His mindset is rather conservative and he will prefer to play it safe, to "feel at home". He will favor a solid sequel over a genuinely novel indie game which would require quite some effort to get into.

The following quote is often attributed to automobile pioneer Henry Ford: "If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses." This describes our middle-rate judge quite well. But what if we are actually interested in innovation and progress?

Objectification 3: The Scientist

Now this is where the absolute experts come into play. Of course this perspective cannot be taken by anyone. The respective judge is extremely well-versed regarding his area of expertise. Therefore we will need several of those specialists, each one responsible for their own well-defined area. They view games as scientific publications, as experiments formulating a thesis and either proving it by working, or discovering certain problems that prevent them from doing so. If executed competently, both will be regarded as valuable contributions to the craft.

Donald Knuth: „We should continually be striving to transform every art into a science:

in the process, we advance the art.“

Lukewarm AAA games on the other hand will be regarded as works simply rehashing the current state of research without adding anything particularly new, i.e. basically worthless. Instead of trying to make predictions about the financial success chances, the scientific judge is interested in what "actually works" and can help advance the medium in the long run. This constant drive to be "ahead of the curve" also means he will likely lose most of the audience and discussion partners along the way. His perspective will seem alien to the majority.

As with other, more mature forms of media though, the sharp eyes of a few creators, critics, academics and deeply involved hobbyists will be what pushes the art form to new heights. Their perspective will be the one able to define the medium's true identity and lay the groundwork for a long-term sustainable future. This will make it possible for the industry to reliable produce valuable games, not just shooting in the dark and stumbling from one lucky guess to the next as before. The place where "I disagree!" will not just be followed by "That's totally fine!" but a thorough examination of the underlying theory, will be the one where the future of the medium will be shaped.

Conclusion

Depending on personal intent, different recommendations can be drawn from the above considerations. Initially, everyone potentially assessing or discussing games should be very clear about whether he or she is actually interested in serious, progressive discourse and its results. Should that be the case, it will become clear relatively soon that uncoordinated opinions and  emotional estimations will not really lead to useful outcomes. Instead the basis for discussion has to be objectified by collectively assuming a common (in itself indeed subjective) perspective. Therefore one has to choose a neutral judge or, more precisely, a joint starting point on the spectrum of game literacy.

emotional estimations will not really lead to useful outcomes. Instead the basis for discussion has to be objectified by collectively assuming a common (in itself indeed subjective) perspective. Therefore one has to choose a neutral judge or, more precisely, a joint starting point on the spectrum of game literacy.

As described above, the clueless judge will not serve as a useful model for too long. Ideally he will lead to a few pointed questions and thoughts over time but not much more. As a next step, the average gamer is definitely able to discuss the medium in a somewhat fruitful, albeit rather conservative way. He is at his best when it comes to market research. Our expert "Dr. Ludo" on the other hand will not be too keen on that topic since he is primarily interested in the intellectual progress of art and craft.

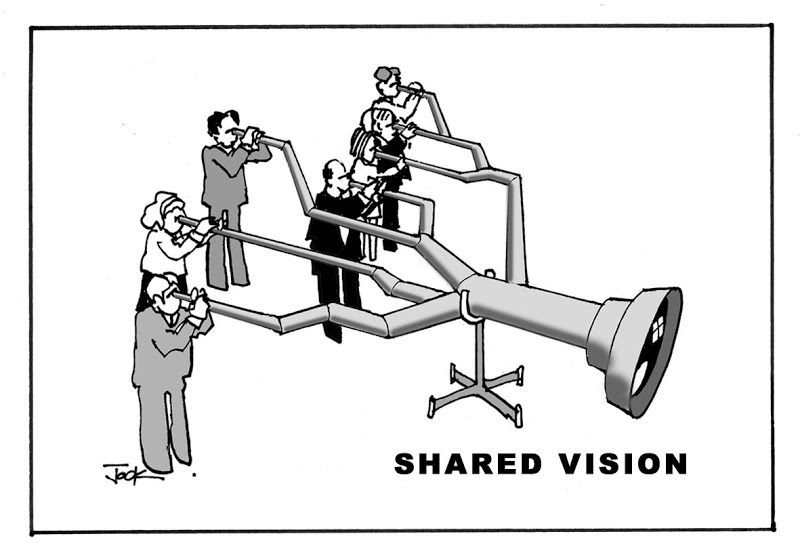

In practice most designers, developers and critics will end up with a "golden middle ground" somewhere in between the two latter perspectives. It can then be adjusted in the direction of popularity and alleged financial safety (Objectification 2), or innovation and research (Objectification 3). From time to time, assuming the naive perspective (Objectification 1) might help refining the mix. In the end the most important thing for development studios, editorial teams, conferences, and basically any group seriously discussing games out there, will be to establish a common perspective. Ultimately this will result in a consistent vision and enable its productive pursuit.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)