Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

The DNA of Candy Crush Saga and Other Successful Match-3 Games

Candy Crush is the dominant match-3 game, making billions of dollars for King, but what makes it unique and is their any variety in the genre? We investigated the DNA of match-3 to find out.

This is the first in a series of posts analysing the most popular games genres. We’re starting with match-3, a genre dominated by Candy Crush Saga (CCS). But CCS isn’t the only match-3 game out there, it wasn’t the first and it certainly isn’t the last. So we wanted to know what makes it different and at the same time find out if it’s fair that every match-3 game since has been described as a Candy Crush clone.

Narrative Except for Bejewelled Blitz all the games featured a map and characters – possible foundations for narrative. Despite this we’re yet to find anyone who could tell us what the story is in Candy Crush, even with all those animated cuts scenes. Of course, puzzle games don’t need a story, Tetris is the most successful puzzle game of all time and there was no narrative there whatsoever. However, considering the investment made in designing characters in these games, could a lack of story be detrimental to licensing opportunities? Angry Birds is the poster child of mobile game licensing, helped by the basic, but still evident, narrative of birds having to destroy pigs. More recently Angry Birds Toons have helped to tell proper stories with the Angry Birds characters. The game had a great mechanic and would have succeeded without a story, but the story has helped the game connect with children and it’s that which has helped Angry Birds monetize outside of the app.

Except for Bejewelled Blitz all the games featured a map and characters – possible foundations for narrative. Despite this we’re yet to find anyone who could tell us what the story is in Candy Crush, even with all those animated cuts scenes. Of course, puzzle games don’t need a story, Tetris is the most successful puzzle game of all time and there was no narrative there whatsoever. However, considering the investment made in designing characters in these games, could a lack of story be detrimental to licensing opportunities? Angry Birds is the poster child of mobile game licensing, helped by the basic, but still evident, narrative of birds having to destroy pigs. More recently Angry Birds Toons have helped to tell proper stories with the Angry Birds characters. The game had a great mechanic and would have succeeded without a story, but the story has helped the game connect with children and it’s that which has helped Angry Birds monetize outside of the app.

Social Only Bejewelled Blitz and Candy Crush scored highly for social, due to the lack of competitive social elements and competitive play in both Mania games and Juice Cubes. Plenty of articles have been written about the importance of social not just for helping to market casual games but to also engage those who play them. It seems odd that three of our five games would miss such an integral feature. Could its inclusion in Candy Crush and Bejewelled Blitz be one of the key reasons behind the success of those games?

Only Bejewelled Blitz and Candy Crush scored highly for social, due to the lack of competitive social elements and competitive play in both Mania games and Juice Cubes. Plenty of articles have been written about the importance of social not just for helping to market casual games but to also engage those who play them. It seems odd that three of our five games would miss such an integral feature. Could its inclusion in Candy Crush and Bejewelled Blitz be one of the key reasons behind the success of those games?

Audio All the games investigated scored highly for audio. Whether it’s cute music loops or the now customary congratulatory messages, the audio in these match-3 titles may be basic but it’s used effectively. The only dropped points came with Candy Mania and Juice Cubes as neither game uses audio to congratulate the player for impressive moves.

All the games investigated scored highly for audio. Whether it’s cute music loops or the now customary congratulatory messages, the audio in these match-3 titles may be basic but it’s used effectively. The only dropped points came with Candy Mania and Juice Cubes as neither game uses audio to congratulate the player for impressive moves.

Gameplay We didn’t score gameplay as how enjoyable the games were, but against the variety of the gameplay and the elements included, such as tutorials, lives and XP. All the games, except for Bejewelled Blitz scored highly for gameplay with the use of tutorials, time limits and power-ups (both free and paid for) being used as standard. What let Bejewelled Blitz down was variety. Whereas the other games changed the objective of each level or introduced new items, Bejewelled Blitz is the same time and time again. As well as variety the other games also featured hundreds of levels.

We didn’t score gameplay as how enjoyable the games were, but against the variety of the gameplay and the elements included, such as tutorials, lives and XP. All the games, except for Bejewelled Blitz scored highly for gameplay with the use of tutorials, time limits and power-ups (both free and paid for) being used as standard. What let Bejewelled Blitz down was variety. Whereas the other games changed the objective of each level or introduced new items, Bejewelled Blitz is the same time and time again. As well as variety the other games also featured hundreds of levels.

Monetization Our monetization vector isn’t linked to the revenue or profit made by the app (all closely guarded secrets) but by the opportunities to spend. The most heavily monetized games are Candy Mania and Jewel Mania. Both of these apps heavily utilised cross-promotion and even included in-game rewards for watching adverts or downloading other games by the developer (Team Lava). With all five apps being free-to-play it’s not surprising to see each opportunity to monetize explored to its fullest. The low score for Bejewelled Blitz is down to the lack of buyable in-game items, such as power-ups.

Our monetization vector isn’t linked to the revenue or profit made by the app (all closely guarded secrets) but by the opportunities to spend. The most heavily monetized games are Candy Mania and Jewel Mania. Both of these apps heavily utilised cross-promotion and even included in-game rewards for watching adverts or downloading other games by the developer (Team Lava). With all five apps being free-to-play it’s not surprising to see each opportunity to monetize explored to its fullest. The low score for Bejewelled Blitz is down to the lack of buyable in-game items, such as power-ups.

Focus on Games

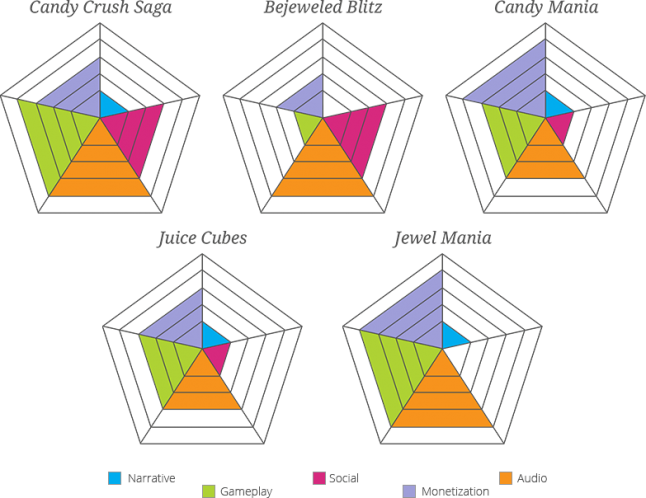

For a different perspective we can look at this data on specific games.

Further Observations

Just because it looks and tastes like Candy Crush doesn’t mean it is Candy Crush

Before I first played Candy Crush I dismissed it as another Bejewelled clone, only to find it was far from it and, in my mind, it is a far better game. It’s like comparing Tetris with Columns, both use falling blocks and have the goal of clearing a screen but they are very different games.

Candy Mania used the goal of having to match a certain number of candies before you finished a level, with each match made adding to the value of the surrounding sweets (it makes more sense in-game). This gameplay mechanic then followed through to a boss battle with each correct match sapping the boss of energy.

Juice Cubes, although looking like a tropical version of Candy Crush, played very differently. Instead of trying to match-3 items together the player is tasked with drawing lines between matching items – like a mix between Boggle and Candy Crush.

New Tricks

Candy Crush has a bad reputation for how it tries to monetize players, a criticism which isn’t fair when looked at against similar games.

For example, Candy Mania has a cute dog as a mascot who does very little until the end of a round. At this point, if you win, the dog gleefully jumps across the screen wagging its tail. However, if you lose he comes into view looking sad, with exaggerated puppy dog-eyes willing the player to play (or pay) for another go. While this is legal at the moment it does bring up ethical questions and would most likely fall foul of the guidelines put forward by the OFT. What’s more, the sad puppy is accompanied by a 10-second countdown, after which one would assume the game finishes. Instead the countdown does nothing aside from accelerate the player’s need to decide whether to play on or not. If the timer runs out the player can still choose what to do, there never was a time limit.

Another tactic employed by the Mania games is to offer the player extra moves before the round is over. At this point the moves are priced at 10 credits (for example), of course the player doesn’t know if they will need the moves yet so buying them is a gamble. If they lose that round they are offered the extra moves again, but this time at a higher price, a tactic that tries to convince players to pay for items they may not need at risk of having to pay more when they know they do need them.

Lastly, while Candy Crush is often seen as not strictly being free-to-play, in that some levels are designed to be so hard the player needs to pay to get past them, at least the level’s difficulty is determined from the outset (as far as we can see). What became obvious during my playing of Candy Mania was that when it became clear I needed certain candy (red ones, for example) to finish a level there was a clear lack of red candies being added to the game board. This happened so often that it became clear the items were not random. There’s nothing wrong with this tactic but it does ruin the idea that you can beat it through skill alone.

And Finally

From our research it’s clear there while there are some common traits in the match-3 genre, such as the use of sound for positive reinforcement and level variety, there’s more to this genre than a bunch of Candy Crush clones. Indeed, while Candy Crush showed the power of social elements some similar games almost ignore this tool all together.

The one constant that we saw throughout our sample was the lack of narrative. Clearly narative isn’t integral to a popular puzzle game, just look at Tetris. But in 2014 could this hold the games back in terms of merchandising or other extrinsic ways of money making? Only time will tell.

How we did It

To start with we identified four of the most popular match-3 games on the market, aside from CCS. As well as popularity we also looked at those which, on the surface, seemed to either influence or be influenced by CCS. We picked:

Candy Blast Mania by Team Lava

Bejewelled Blitz by PopCap

Jewel Mania by Team Lava

Juice Cubes by Rovio

We then spent a couple of hours playing each game. To keep the comparisons fair we played all five games on an iPad. During the playthroughs we noted the mechanics and gameplay elements that made up the game – from the use of narrative to the number of levels. This data was put into two documents, ‘data’ and ‘findings’. The data comprised of five headings:

Narrative – How story played a part in the game

Social – How communication was factored into the game

Audio – The game’s use of sound

Gameplay – Elements included the number of levels, use of lives and challenges

Monetization – How the game attempted to make money

Each heading then had a number of elements under it, with each being scored from zero to three.

0 – Not present

1 – Present but not significant

2 – Present and used occasionally

3 – Present and significant

We then used a custom algorithm to give each of the five sections a score out of five and plotted the results as vector diagrams for comparison.

To accompany the vectors we also made detailed notes on how the games played. This allowed us to pick up finer intricacies that wouldn’t be apparent in the vector diagrams.

If you would like to be sent the complete spreadsheet, please fill in this form. You can view similar articles on our blog.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like