Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

How to Design a Survey for User Feedback

This article provides an introduction to survey design, while taking a look at three different survey types (with examples), good practices to consider before and after distributing surveys to players, and links to additional resources.

INTRODUCTION

As indie developers we continually strive to gain insights that can be used to improve our games. Observing people playing a game is the best way to gauge what players are feeling, their behaviors and attitudes, and if game mechanics are having the desired effect. On the other hand, when I’m spending half an hour or more to observe a person, these observational studies are time consuming and dependent on my location. Over the course of one eight-hour day divided into 30 minute observational study sessions, I could gather 16 responses from players. I’m not able to gather feedback from 1) a large number of players and 2) players in different locations. So how does one go about receiving constructive and meaningful feedback?

As an indie developer with an undergraduate degree in psychology, I’ve chosen to employ the survey method to learn more about how players respond to game mechanics and if User Interface or User Experience (UI/UX) decisions reflect my creative intentions. Time is of the essence for all developers so I wanted to share some of the things I’ve learned, with hope that they might help your own player feedback process. Before we begin, the purpose of this article is to outline a framework that can be used to conduct survey research. While this article will not include what to say or what to measure (these components are unique to each project and project phase!), it does cover the basics of good principles and design practices from quantitative research methodology. Additional resources will be added throughout the article for further insight. Still interested? Then let’s dig in!

What is a survey?

The survey method is a research method, a tool, used to collect information from a representative sample of a population. In the case of the indie developer, a representative sample will be of your players. This collection of information can be used to learn about players’ self-reported attitudes, opinions, and behaviors. Surveys can be distributed online, in-person, on paper, or even over the telephone — awesome options to capture attitudes and opinions from all over the country (even globally if localization is considered).

The Pros and Cons of the Survey Method

As with all research methods, this method has its own pros and cons. The pros of survey research that appeal to me most as an indie developer are cost-efficiency, ease of gathering large amounts of data, practically no constraints on geographical location and demographics, and quick results — in other words… time and money. While a survey’s construction can take considerable effort, the player’s role in filling it out usually takes a short amount of time.

But keep in mind that surveys are not ideal for controversial issues as individuals might be unfamiliar with or have difficulty remembering relevant information. An additional reason for this is that individuals may feel societal pressure to respond in a manner that will be viewed favorably by others, a social science term called social desirability bias. Another challenge when using survey design is that surveys have inflexible design (you can’t change anything about the survey once you’ve started to administer it). The reasons for this inflexibility is to maintain the validity of collected data.

Validity and Reliability

In psychological quantitative research methods, a strongly built assessment will demonstrate both reliability and validity. These two components are the foundation of a well-designed survey. So what the heck do they mean? It’s important to note there are different types of validity and reliability within psychological research and that this section will cover the basics.

Validity: A test is valid if it measures what it claims to measure. For example, a test measuring the emotional attachment to a set of characters should not something else such as the UI/UX design. Another way to think about it is if I’m trying to measure a player’s attitude of a game’s level difficulty, am I asking the correct questions to be able to gauge that?

Reliability: The consistency of a measuring test or research project. For example, say I were to measure my work in Adobe Photoshop in pixels and the next day measure it in inches. Though the measurements might take up the same amount of space, the readings are not consistent with each other. If findings from a survey can be consistently repeated, they are reliable and can be useful!

As we bear these concepts of validity and reliability in mind, let’s take a look at several basics on how to design a survey. Before survey questions or statements are created, we need to determine how they will be measured.

3 TYPES OF SURVEY FORMATS

The Likert Scale

One form of measurement is the Likert Scale and it is so commonly used that you have probably taken a survey that used a Likert Scale before! Have you ever been asked to complete a series of statements that use a rating scale to gauge your levels of satisfaction or agreement or your attitudes about frequency or importance? That, my friends, was most likely an example of a Likert Scale.

Developed in 1932, this method was designed to 1) measure attitudes or opinions and 2) the intensity of these attitudes or opinions in 3) a response format of fixed choice. This type of survey poses statements rather than asking questions. Participants are asked to notate how much they agree or disagree with a statement by using a pre-determined scale system. The fixed choice format allows participants to express the intensity of their agreement or disagreement with each statement. A wonderful benefit of using the Likert Scale is that statements don’t force participants to express an either-or opinion and does so in a time-efficient way.

Several considerations to take into account when using this method include:

Some personalities have a tendency to avoid “extremes.” Such personalities select answers in the middle of the scale. A way to decrease this tendency is to make the survey an anonymous survey.

Previous questions can influence participant’s answers or thoughts. To counteract this, avoid the use of leading or subjective statements.

The scale cannot capture the exact attitude of an individual, it is only an estimate of attitude. Open questions can be used at the end of the survey to gain information on exact attitudes (see next section).

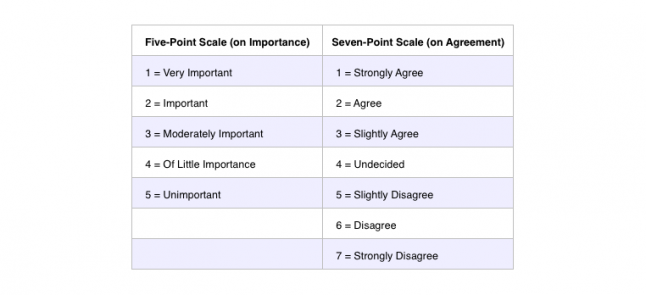

When designing a Likert Scale, it is common to use a five-point or seven-point scale. Each point on the scale is assigned a number as seen below (1 = Strongly Agree, etc). These correspond with a direction that measures intensity (strength of feeling) in positive and negative directions. Here’s an example of the five-point and seven-point scales:

See how each number is associated with a response — and is associated in such a way as to be a clearly defined direction? On the five-point scale we see a range of importance, from very important to unimportant. On the seven-point scale we see a range of intensities of agreement to disagreement. The direction of each scale and which number is associated to a response will be used to calculate your participants’ feedback.

There’s great debate on which scale is better to use. One thought is that seven-point scales produce better distributions of data. Another thought is that the five-point scale is easier for participants to understand and answer. So it’s up to you and your team to determine which scale to use based on what you want to accomplish.

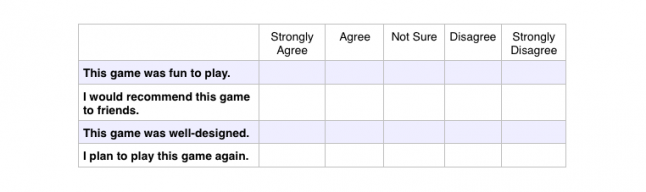

Say I made a hypothetical game called ‘Castles Above and Below’ and I want to know if I should increase my marketing budget to attract new players. But first I need to find out if current players enjoy 'Castles Above and Below' or if I should make improvements before a big marketing push. Using a hypothetical survey to measure what the attitudes of my current player base are, a part of my survey might look like this:

Now to gather the feedback, let’s say I received 50 completed surveys from players. I begin by taking a tally of each response category per statement.

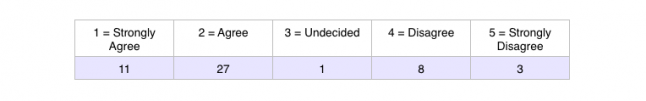

We’ll begin with the first statement of “This game was fun to play.”

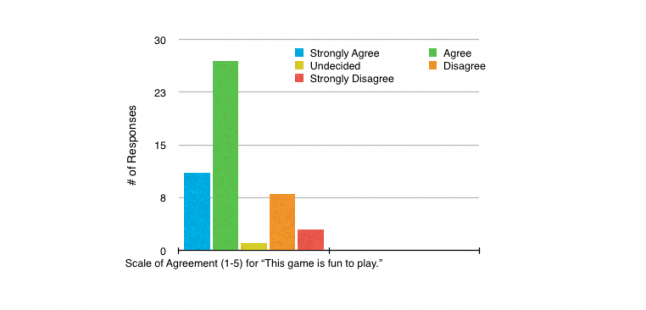

At this point, it’s important to note that social science researchers create manual groupings of data or use software (SPSS or Excel) to calculate in-depth data analysis. To easily interpret the data above, I am going to use the mode, the number reported most often. In this case, I’ll use the hypothetical data I’ve gathered to calculate the mode of “This game is fun to play.” The mode of this statement is 27 for option 2 (Agree). I conclude that most players agree this game is fun to play.

If all of the statements on this hypothetical survey receive similar scores then my data indicates that I can confidently allocate more of my budget to customer acquisition. Though the example above makes this survey method seem overly simple, the eventual data collection of statements and attitudes will build a more complete picture. The use of a Likert Scale is a great way to learn what players think about a game (regardless of whether it’s completed or still in development).

If visuals are your preference, pie charts and bar graphs are a great alternative to represent data (as seen below).

Reverse Scores

Participants are asked to rate the direction (strength of feeling) of the statement e.g. positive to negative. Before the introduction of reverse scoring, all statements or questions would be answered in one direction e.g. from agree to disagree. Once we tally the results of a survey with no reversed items, our tally will most likely contain a majority of low OR high scores.

Reverse scoring means the researcher poses a statement or question in way that will be scored in the opposite direction on the scale. With this technique, statements or questions can now be answered in both directions (agree AND disagree).

So what’s the point of reverse scoring? Reverse scoring is used to counteract the tendency to respond to a range of statements on some other basis than the specific content of each statement, a phenomenon in psychology known as “response bias.” Let’s take a look at an example of a reversed statement then follow up with how to calculate these statement types.

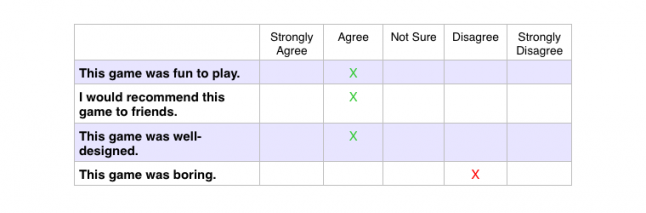

Example of a reversed item in a survey:

This game was fun to play.

I would recommend this game to friends.

This game was well-designed.

This game was boring.

If we were to answer the items on a scale, the first three statements would point in the same direction while the fourth statement would be answered with a rating on the scale that would point in the opposite direction. Here is an example to illustrate the difference in direction:

We derive that the participant who filled out this survey thought this game was fun, well-designed, and would recommend this game to friends. Because they all point in the same direction, they’re known as positive items. The fourth answer demonstrates the participant’s full attention and reinforces his or her attitude. Now what do we do from here?

To calculate reverse scored statements so the numerical data makes sense, we reverse the rating on the fourth statement (this reversal means this statement can also be referred to as a “negative item”). The statement, “This game is boring.” received a participant score of 4, “Disagree” but we will reverse the score when we compute the data. Instead of rating it as a 4, we rate it as a 2 because the participant thinks the game is NOT boring.

The reason we reverse the score of such statements is to obtain a single score reflecting the intensity in a single direction. If we left the fourth score as it was answered, our data wouldn’t make any sense when we calculate the mode. If the participant had answered all four statements with a ‘2 = Agree’ then we would conclude that the participant was not paying close attention and we would exclude that participant’s survey responses from our pool of data.

Several tips to consider when using reverse scoring:

Counterbalance your items by including reverse scored items (reversed scored items should be interspersed so 1) two consecutive items aren’t asking about the same thing and that 2) two consecutive items aren’t reverse scored items).

When first developing the survey, sometimes it’s easier to come up with survey statements pointing in a positive direction (positive items). Then those statements can be converted into reverse items (negative items).

Ask your participants to read through the survey carefully as the statement items are sometimes written in a way to gauge the attention of the participants.

Researchers use a variety of survey methods — some stick to one format type while others use an assortment of survey types. Feel free to experiment with what assessment types might work best for the type of information you’d like to collect. Also, don't forget that we have covered three types and many other options exist (e.g. multiple choice surveys, ranked surveys).

Phew! I applaud you, if you’ve stuck with me this far. *grin* I hope this information has been helpful! Now that we’ve covered different types of measurement formats, here are several simple ways to stick to good survey design.

Keep It Simple

Use simple language. Avoid jargon, technical terms, and acronyms.

Avoid double-barreled questions. A double-barreled question is a single question that asks about more than one issue but is limited to one answer. “I found this game to be challenging and fun.” The matters of challenge and fun are two separate issues.

Refrain from using double negatives in a survey.

Beware of leading or loaded questions. We don’t want participants to say what we want them to say, we want their own opinions.

BEFORE & AFTER: GOOD PRACTICES TO CONSIDER

Standardization

We begin with standardization. Important to research methodology, standardization means assessments are administered and scored in a consistent and objective way — from the way instructions are presented to the environment participants are in when they take the survey. Standardization is critical to research so researchers can eliminate ambiguity, establish norms, and arrive at legitimate conclusions.

Now, indie developers typically won’t usher all of their players into a room in sets of five, with 10 minutes to take a survey. But we can help to standardize the process by ensuring the same survey is distributed to every participant (including the order of questions), similar instructions are given to every participant, and that participants are not interrupted.

Pilot Test

Once you have built your survey, it’s time to test it! A pilot test is a great way to make sure your survey’s content is easily understood by others and it is an easy way to check for typos, discover any unclear instructions, or find words that could confuse your participants (big words, technical words, etc). In addition, it gives you an opportunity to practice standardization when providing instructions to your participants! When the pilot test has been completed and your edits made, it’s time to introduce your survey to the public.

Debrief

Traditionally used in psychological research, a debriefing is a structured conversation between the researcher and participants to address and discuss the study and provide an opportunity for participants to ask questions. Only used once an experiment or study has been concluded, the researcher is able to relate what the purpose of the study was and to share any relevant or significant findings. Though typically a formal process, this can be adapted to fit the more casual environment of the indie developer.

As indie developers, this is a nice to have rather than a necessity but keep in mind these people have given you the invaluable gift of their time! These individuals are the ones who have not only played your game in a testing phase but have also given you direct feedback. A casual conversation about the survey or providing a way to directly contact you for future information about the results of the survey is a great way to stay connected with your players!

Comments & Contact Info

I hope this article has been helpful to you and your development process! If you’re new to survey design, don’t be afraid to fail a few times. Survey design is an art in itself. I invite you to share your own experiences with survey design and distribution in the comments below. What tips or tricks do you use? Are there other ways you prefer to measure and analyze player feedback?

Thank you for checking this article out! I realize I left a lot of territory uncovered on this topic so please feel free to drop me a line in the comments section or reach out to me directly via Twitter.

____________________

With an academic background in psychological quantitative and qualitative research methods, Nefer uses this knowledge to help improve player experiences at NDXP Games.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Validity and Reliability

More Examples of Validity and Reliability (with great visuals!):

Martyn Shuttleworth (Oct 20, 2008). Validity and Reliability. Retrieved Feb 23, 2015 from Explorable.com: https://explorable.com/validity-and-reliability

Different Types of Reliability and Validity:

Jonathan Howell, Paul Miller, Hyun Hee Park, Deborah Sattler, Todd Schack, Eric Spery, Shelley Widhalm, and Mike Palmquist.. (1994 - 2012). Reliability and Validity. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University. Retrieved Feb 24, 2015 from http://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide.cfm?guideid=66.

Likert Scales

Likert Scale overview and examples:

Unknown. Measuring Attitudes. Retrieved on February 25, 2015 from http://psychology.ucdavis.edu/faculty_sites/sommerb/sommerdemo/scaling/attitude.htm

Likert Scale measurement examples:

McLeod, Saul. (2008). Likert Scale. Retrieved on February 27, 2015 from http://www.simplypsychology.org/likert-scale.html

Standardization

Standardization Examples:

Christopher Heffner (Unknown). Chapter 1.5 Standardization. Retrieved Feb 27, 2015 from http://allpsych.com/researchmethods/standardization/#.VPDXJXZZUys

Pilot Tests

Pilot Study Advantages, Types, and Results:

Sarah Mae Sincero (Jan 21, 2012). Pilot Survey. Retrieved Feb 27, 2015 from Explorable.com: https://explorable.com/pilot-survey

Debriefing

Debrief, Informed Consent, Deception, and Participant Protection:

McLeod, S. A. (2007). Psychology Research Ethics. Retrieved Feb 27, 2015 from http://www.simplypsychology.org/Ethics.html

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)