Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

A comprehensive look at the quality of life issue from EA_spouse onward, this article surveys the efforts of professional organizations, whistleblowers, studios, and governments to protect the rights of game developers.

January 9, 2013

Author: by Johanna Weststar

It is cool to work in the video game industry. You get paid work on games, right? This image of the video game industry as a cool, hip, fun place where you get to make cutting edge titles has some truth, but it also hides a dark side.

The dark side sometimes shadows the light -- like when Erin Hoffman made her now famous post as ea_spouse. And it appeared again with the allegations of Rockstar Spouse, 38 Studios Spouse, the investigative journalism of Andrew McMillen about the making of L.A. Noire, the IGDA press release about KAOS Studios, through IGDA reports about quality of life, and through conference panels, blogs and forums.

The dark side also emerges when you talk to individual game developers about their working conditions and the risks that they face. Developers say that they face challenges with sustained long working hours ("crunch"), unlimited and unpaid overtime, poor work-life balance, high incidence of musculoskeletal disorders and burnout, unacknowledged intellectual property rights, limited crediting standards, non-compete and non-disclosure agreements, and limited or unsupported training opportunities.

Most developers have stories of long hours: "[I work] an average 10 hours a day; there's days I would put 16 hours in, there's days where people stay overnight. It can get really hectic -- I mean, I was chastised for leaving," said one.

Another explained that the willingness to work is related to the passion for the job, but that this is manipulated. "That's pretty much what seals the deal. If a project is interesting enough, people would put up with anything. They will work crazy hours if they love the project... So people will go, 'Oh yeah, it's going to be a great game.' So they use that -- a company uses that to make people do more work than they should do..." Managers seem completely conscious of this manipulation. One lead said, "I never had to say 'you have to stay,'" but acknowledged that he uses a more subtle tactic:

But usually it's just, I think if your team and you get along, you can phrase it in a way that makes them understand that it would be really, really great if you could stay, and it will be greatly appreciated. But in other projects, people are tired, the project been extended and crunching for ages and then people are close to burn out, you know, some people are just... They practically sleep at the office, so...

These guilt-based tactics and veiled threats to career progression work, and also avoid the legal pitfalls of forced overtime. "I've never had a place that could physically chain me in the building, but the influence of the social and sort of -- not just social in the terms of peer pressure, it's like, also, you know that you have your career in their hands and if you... as a team player, that's going to ensure your progress within the company," explained one developer.

Are video game developers doing anything about these challenges?

Interviews with video game developers in Montreal, Canada, some sneak-peek data from the 2009 IGDA survey, and a canvassing of the social web show that disgruntled workers are speaking out and resisting in a variety of ways, both as individuals and in groups.

There are a number of individual actions that all employees can do if they are unhappy with their work situation. The easiest thing to do is quit and find a better situation somewhere else. The attitude of "if you don't like it, leave" is something that is heard often in the game industry. "In a sense it may be easier to go and start up your own company and do contract work... than it is to try to get a big company to change its ways," said one developer. In the face of a dispute, one developer said that rather than suing the company or going to the "labor people," "It's probably more worthwhile and cheaper just to find another job in the industry. We get fired and get hired at another place all the time."

Some people convey a sense of toughness or machismo about "surviving" an epic crunch, and these episodes become part of the lore of the industry. "I was there when..." This means that those who do not survive or who complain are sometimes considered as those who can't take it -- "this industry is not for you."

Other video game developers take personal advantage of the mobility of the industry -- particularly in regional hot spots or clusters where a lot of studios exist. Here, good developers can be head hunted away from competitors and dissatisfied developers can look for greener pastures. "Employers are waiting in line at my door," said one. "Yeah, we get a lot of calls," said another, adding that "There's a lot of headhunters. There's a lot of employee-pilfering... even inside here."

But this attitude doesn't fix any problems for the long term. If you don't like your work and you quit, your employer just hires someone else. Turnover has to be pretty bad before an employer will change their policies to fix it. You might be able to find a better job in the industry, but most studios operate the same way, so you are probably just getting into the same environment all over again. It could also be worse -- and then you are out of the frying pan and into the fire. You could leave the industry forever, but that sucks, because you like making games. If you are awesome enough to be headhunted or negotiate a personal deal, good for you. But that doesn't help anyone else.

Perpetual turnover also doesn't help the industry as a whole. It is expensive and wasteful to let people with learned studio-specific knowledge continually walk out the door, only to have to reorient the newcomers. High mobility hinders the industry's ability to mature and stabilize. This also creates the conditions where supporters of the status quo succeed and those with diverging opinions are chased out -- this can lead to groupthink and stagnation because no one can see a different way of doing things.

So, what else do developers do?

Some engage in sabotage. This is another thing that all employees do. Sabotage can range from minor (you take some of the office stationery home) to more serious (you vandalize equipment). In white collar or knowledge work, a serious form of sabotage is leaking important or confidential information to competitors or the press. This is very risky because this can threaten the employee's reputation -- and the employee can often rightfully be sued, because of all the NDAs in the video game industry. This is not a common, nor very fruitful action for dissatisfied developers who want to remain in the industry.

A unique form of sabotage particular to the game industry is to drop an "Easter egg." This is used specifically to gain credit for work. The acknowledgement of intellectual property rights and the proper crediting of the people involved in each game is a sticky issue in the game industry.

With crediting largely unregulated, individual developers often have to bargain from scratch. Their success is highly dependent on their individual skills or their specific context. The practice of dropping these coded signatures within the gameplay became a way for developers or teams to make their mark.

This did have an effect in drawing attention to the issue of crediting, and the search for Easter eggs and decoding their meaning is great fun for hardcore fans. But, it is only one response to one challenge, and not as common, nor as easy, as it once was.

Some developers complain or make suggestions when they don't like something about their working conditions. This is called having "employee voice." Some of the developers that we interviewed said that their studios had formal policies for managers to listen to employees. Some referred to "open door" policies. One was more specific: "Managers, for instance, have to allow a certain amount...30 percent or so... of their time, or more, to answer employees' queries in general."

Our interviewees were mixed as to the extent and intent of employee voice mechanisms, like general meetings and open-door policies. Some thought that many senior and HR managers are open to such one-to-one discussions. As one developer said, "It's important to have a voice, otherwise you don't really feel that you're... You know, you're just there, you're not contributing. I'd say for the most part, if I feel strongly... I could take the effort to bring it to the attention of the upper management." As well, some women in particular reported gratitude for specific arrangements they received regarding work-family balance.

Others had mixed feelings toward the role of HR in helping employees. One said, "Sometimes they feel like they are not necessarily there to help you, because they are employees of the company." Another intimated that HR is complicit in perpetuating the negative norms of the company -- "Because a lot of people, even in HR, have a kind of 'well, you know how it goes' way."

Open door policies and other mechanisms of employee voice are not a universal norm in the industry and, like other workplaces, success often depends on the manager or team lead involved. In a 2010 blog post that was widely and favorably received on the web, Insomniac Games' Mike Acton shared his tips on how to be a good manager. He wrote:

One-on-ones: This is probably one of the most important aspects of my job. I do my best to meet with 20-something people for at least a half-hour, at least once every two weeks. For sure, that's a lot of time. But no time is better spent than this. It's an opportunity to listen. Every person is different. There is no "format" for these that works for everyone. Sometimes it's about technical advice and feedback. Sometimes it's about personal issues. Sometimes it's about the day-to-day struggles of development. But whatever it is, it's always about letting each person simply tell me what's on their mind and doing my best to help them, as best I can, grow as professionals.

Acton goes on to say that even these one-on-ones aren't enough: "It's fine to have an 'open door policy'. But more than that, it's necessary that I constantly seek feedback. I can't just wait for someone to come to me with a problem or suggestion. I need to use every tool at my disposal to figure out what's on people's minds. That's absolutely part of my responsibility."

This shows that successful employee voice requires trust and commitment on both sides of the managerial divide. This is not always easily built, and is definitely not built within times of conflict. For successful voice, employees must speak up with legitimate and reasonable concerns and employers must take their comments into real consideration.

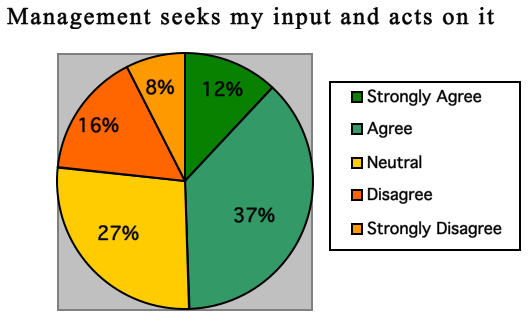

There is a real sense in the video game industry that mistakes are repeated time and again; that managers, leads and development teams themselves do not learn from their mistakes despite the post-mortems. In the 2009 IGDA Quality of Life survey, developers were asked if management seeks their input and acts on it. One quarter said no. Over one-quarter were "neutral"; they couldn't decide. Only 12 percent strongly agreed that management sought and acted upon employee input.

Voice is a superior option than quitting or sabotage if the complaints or suggestions are received and produce positive results. Exercising employee voice also has more potential than employee exit (quitting) for the problem to be addressed for more than just one person.

When managers hear of a problem from an employee and act to resolve it for that employee, they may also permanently change policy for all employees, or at least consider their past decisions to maintain equity of treatment. Some of our interviewees did say that changes don't come easily and swiftly, but they do come if the issue is supported by a mass of employees or is particularly sensitive. "So there is an attempt to proactively respond to people, but in the aggregate," said one.

On the whole, according to those of our interview respondents who had voiced grievances, the workplace offered an ongoing discussion. That said, voicing your grievance is not a guarantee of it being addressed. And managers can cut side deals with individuals that do not benefit anyone else. This is called arbitrary treatment, and though it can have great outcomes for "superstars" or others management wants to appease, it is never guaranteed, and can create a lot of inequity. As we will discuss more below, the context of voice also matters. As one developer said:

They are really happy when you are in a meeting with your manager, privately talking about your salary and your performance, and you're having a say with HR. I think they are not so happy if you would go out and say, start a blog, or talking about how you or your spouse was very abused of their job -- and that forces them, a little more, to deal with the problem. So, having your say is contextual. Like you can have it, but they probably would rather have you talking directly to them, which doesn't give you very much ground to stand on. The public way could be dangerous for them, and they don't like it at all... So, it's not cool with them if you're saying publicly things that contradict... That can potentially damage the corporate line, especially if it's a publicly traded company, or something like that.

Another action that dissatisfied employees can take is to sue their employer. But employers have a lot more resources than employees, and sometimes the law might not be strong enough to support some employee complaints. Sometimes legal action can be more successful and less of a burden when done collectively. This also solves the problem for a larger group and is more likely to ensure permanent changes to the system. There have been some successful class action lawsuits in the video game industry -- especially over unpaid overtime.

Programmers and graphic artists have launched and won a number of suits of this nature against Sony (Wilson v. Sony Computer Entertainment, Inc.), Electronic Arts (Hasty v. Electronic Arts, Inc.; Kirschenbaum v. Electronic Arts, Inc) and Vivendi (Aitken vs. Vivendi Universal Games). These settlements totaled more than $39 million, and affected over 1200 employees. The settlements also resulted in the reclassification of many employees to be below the pay and responsibility grade that would make them exempt from receiving overtime pay.

Video game developers have other options for collective action as well.

The industry has a non-profit professional association in the International Game Developers Association (IGDA). According to its webpage, the IGDA mission is: "To advance the careers and enhance the lives of game developers by connecting members with their peers, promoting professional development, and advocating on issues that affect the developer community."

This is important, because high-tech labor markets such as new media and video game development have high mobility and limited employer investment in training; therefore, professional associations play an important role in improving their members' opportunities for finding employment in the regional labour market, helping them to improve their skills, and improving their individual negotiating positions.

According to the work of Chris Benner, Associate Professor at UC Davis, professional associations or guilds are seeing a resurgence in high-tech sectors (i.e., System Administrators' Guild, HTML Writers' Guild, Silicon Valley Web Guild).

In a 2003 article, Benner cites the words of Kynn Bartlett, founder and then president of the HTML Writers' Guild. "The term 'guild' was chosen to look back at the older, medieval-type guilds. What we liked from that model was the notion of sharing knowledge -- that building web design was something of a craft... [The term 'guild'] keeps in mind the main purpose... sharing information to make everyone successful."

However, these contemporary guilds and the IGDA do not have the same leverage as legal unions. Most importantly, the IGDA lacks the ability to exercise monopoly control over access to skilled labor. It does not regulate and restrict entry into the industry through certification and exams like other professional associations (i.e., doctors and lawyers) or like the apprenticeship systems of the craft unions. It also cannot enforce restrictions on production standards or bargain working conditions on behalf of its members.

In recent years, the IGDA has shown some interest in more direct collective action. It offers a pooled health and benefits plan for members and supports volunteer special interest groups (SIGs) on key topic areas. The Quality of Life SIG advertises a grievance committee to "manage complaints from IGDA members about employer policies that are in contravention to IGDA standards."

Examples of committees that set standards are: crediting and intellectual property committee, anti-exclusive clauses committee, and quality of life committee. On a number of occasions, the IGDA has published press releases encouraging accused studios to curb excessive overtime and other poor working conditions and indicating their intention to further investigate employee claims (i.e., KAOS Studios, Rockstar San Diego, Team Bondi).

The challenges faced by the IGDA are its reliance on volunteers and its lack of real power to impose sanctions. The IGDA can say that it is displeased, and many studios will respond to this negative "peer pressure" and the bad press it garners. After all, studios are trying to attract the best people to work for them. But there is no fallout if the IGDA is ignored. The organization must grow more powerful for that to be the case.

Another form of collective action that people in the game community have used is "whistleblowing," or mobilizing over the internet. One of the first cases was the emergence of the anonymous virtual union "Ubifree" in December of 1998. The group described working conditions at Ubisoft in France, and sent a call for Ubisoft employees around the world to join the union. The small initiative harvested a wealth of supportive messages, many of them denouncing the working conditions.

After only a few months, Ubisoft management announced some improvements and the anonymous group closed down the website/union. One improvement was the addition of an employee representative in a few committees; however, this representative was never granted any decision-making power. Recently, the Ubifree 2.0 site has also been launched, with what appears to be one person's account of the working conditions of Ubisoft Montreal.

A more successful episode known to all in the industry was the "EA Spouse" affair. In November 2004, the fiancée of a developer (later revealed to be Erin Hoffman) used her LiveJournal blog to denounce an abusive situation of constant crunch time in Electronic Arts' Los Angeles studio. Similar to the Ubifree movement, her post received thousands of comments from gaming fans and beleaguered developers at EA and other studios. This rallied a movement against EA in particular and crunch time in general. EA later banned work on Sundays and adopted a policy favoring five working days a week.

Other tell-alls or exposés have followed, such as Rockstar Spouse, 38 Studios Spouse, and a series of articles by investigative journalist Andrew McMillen about Team Bondi studio. Each received a large number of supportive or appreciative comments and were discussed widely across the game community and in the press. But none reached the notoriety or impact of EA Spouse.

This raises the question of the efficacy of these actions. It could be argued that the success of EA_spouse in motivating change was due to a confluence of factors: It was the first instance of whistleblowing about unpaid overtime and crunch, so it was incredibly cathartic to those in the industry and a real shock for those outside the industry who thought the industry was a hallmark of the new, decent, knowledge economy jobs. The timing of the post also occurred in conjunction with a class action lawsuit against EA. We now know, of course, that EA_spouse's husband was a lead plaintiff in that case. The IGDA published its first Quality of Life white paper in 2004 as well. All this means that there was a considerable amount of energy devoted to the issue of crunch at that time.

The recent Occupy movement was amazing in its ability to raise consciousness and mobilize a large population without any formal leadership. Indeed, the lack of identified leaders and spokespeople was heralded as a central feature in the grassroots and democratic ideals of the movement. However, most social movements require leadership to collect, magnify and channel the dissatisfaction of its followers.

In the wake of EA_spouse, Erin Hoffman emerged as a leader and spokeswoman for the Quality of Life movement -- but additional, ongoing, formalized leadership is lacking. Hoffman's self-regulating industry watchdog website Gamewatch has seen only sporadic activity over the years. At the level of the IGDA, the association has been in transition, with a number of executive directors; there is uneven output from the various committees. Arguably, the energy has ebbed.

The more recent outcry against crunch and unpaid overtime at Rockstar San Diego by the "Wives of Rockstar" was essentially identical to Erin Hoffman's plea, but received comparatively less attention than EA_spouse. A Rockstar employee posted a comment under the name Code Monkey 20 days after the Wives' original post. It is illustrative of the fragility of the movement, and the ability of management to appease disgruntled workers with the promise of better things to come:

...R* management have informed its San Diego employees that everyone will be given a generous and extended break after the product conclusion. Maybe I feel a bit guilty about venting in a public place about any negative aspect of a job I still adore, especially now that I've read a few press snippets that have taken quotes of my writings slightly out of context. I don't think anything I ever said was "damning."

Since no one else has, I'll say that I feel our concerns have been responded to one way or another, and it has been favorable. I think it should also be said that the long mandatory working hours for this project, at least for my own tenure, are unprecedented at San Diego in particular. They've told us that it certainly wasn't their intention to extend working hours in such a manner, and I believe them. I think we'll all pull through just fine, we'll get our time off, and I don't see this situation happening again anytime soon.

My apologies go to Rockstar for not anticipating that anything I said here could possibly have a negative impact of some kind.

In this case management apologized, gave a one-time reward, and deflected blame. It is unknown whether lasting changes were made to the problems in the development process and decision-making hierarchy that were credited with creating the "death march" by these developers. The Ubifree movement was also quickly silenced with only cursory appeasements from management.

Spontaneous action on the internet is invigorating, but if all it does is create a short-term media buzz and collect anonymous missives of support, there is not much lasting momentum. As Paul Hyman asked in his May 13, 2008 Gamastura Feature, "Quality of Life: Does Anyone Still Give a Damn?"

So what should video game developers do? What do they want to do?

An additional action is possible, and that is the formation of a legal union or guild. This seems like a very large challenge, because most assume that the perception of unions in the game industry and in other high-tech industries is negative. But some prominent voices are in favor.

In a March, 2005 Gamasutra article on unionization, Paul Hyman quoted attorney Tom Buscaglia as saying, "I'm just not sure there's a way around it." In the same article, Erin Hoffman was quoted, saying, "...the only thing that will get publishers to budge is unionization, which I believe to be the best solution."

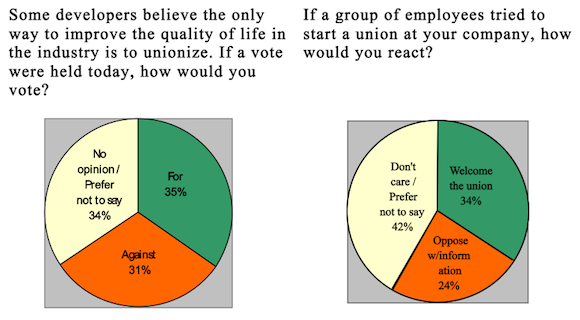

And the 2009 IGDA Quality of Life Survey shows that they are not alone. The following graphs show developer responses to two questions on unionization.

These results are more positive than some would have anticipated, but there are still a number of features of the traditional union movement that seem antithetical to the work of game development.

High mobility among video game developers is a powerful deterrent to unionization in North America because the certification and bargaining model is "enterprise-based." This means that individual unions or union locals of the same parent union are formed on a studio-by-studio basis, so all the negotiated advantages held in a collective agreement are linked to the ongoing employment relationship at that studio. This model does not fit a highly mobile industry where workers move from project to project and studio to studio; it is not worth it to fight for individual conditions at one studio if you do not intend to stay. It is also the reason people say that unions will increase production costs at one studio and make them uncompetitive compared to the guy down the street.

Mobility also poses challenges to typical union pay structures, which are based on seniority and long term service. Many see unions as anti-creative and antithetical to the meritocracy system that anchors excellence in technology-based industries.

Seniority is seen in direct contrast to the recognition of merit and to developers' self-perceptions as high achievers who continually learn, enjoy challenging assignments, and advance based on accomplishment. In this environment, reputation and skills are a driving factor to success, not necessarily time on the job. This was actually the consolation prize in the Rockstar San Diego case.

Several comments in the "Wives" online thread consoled the beleaguered team, saying that the boost to their reputations from delivering an amazing game under extreme conditions would be worth it in the end. One called it a "golden ticket"on their future resumes. They are trapped in an informal reward and punishment system linked to building a desired reputation. They are promised future benefits and rewards if they consent to overtime, but are threatened with a professional stall-out if not.

So, are unions not a viable alternative? Perhaps not in their traditional form, but other models are possible.

An industry-wide, multi-employer certification and negotiation process can address many of the above obstacles to unionization. This means that individual developers would not join a union or a union local at their studio; similar to the scope of the IGDA, they would join a single union representing video game developers across the industry -- nationally or even internationally. The agreements bargained between this union and an association of video game employers would set the standards across the industry and therefore remove the issue of studios competing against each other.

Other systems like this are in effect elsewhere. European countries are known for their centralized industrial relations systems, where most minimum standards are negotiated between unions and employer associations at the industry level. The auto sector in North America regularly engages in "pattern bargaining," where a standard template is applied across the main auto manufacturers so that none are disadvantaged with respect to the other. Unions in the film and television industries have been working under similar systems for decades.

A further legislative option can be found in Status of the Artist legislation that stems from a 1980 UNESCO recommendation. A form of this legislation is in place at the federal jurisdiction in Canada. A variant, An act respecting the professional status and conditions of engagement of performing, recording and film artists (RSQ c. S-32.1) exists in the province of Québec, Canada. This system for the performing trades allows for social insurance plans that follow you throughout your multiple employers and is an early adopter of the principle of portable rights as is used in the U.S. film industry.

Under this system, artists can also benefit from the state's health and security plan, and co-regulate the sharing out of incomes drawn royalties and residuals. Moreover, the act's provisions for respecting professional status can cover the appreciation of merit. This system promotes a minimum standard hiring contract, but allows for better conditions should the artist be more in demand or more prestigious. Similarly, individual negotiations or "above-scale deals" are a long-time industry practice in the motion picture and television unions.

In the 2009 IGDA Quality of Life survey, 64.2 percent of the 2,506 developers who responded were poorly informed about the labor laws where they live, and 63.4 percent said that they did not feel the laws would protect them sufficiently should a grievance arise with their employer. In material terms, developers are not void of motives for collective action, and yet their current individual and collective means seem unable to fix systemic problems in the industry.

Unionization is an option, but it will not be successful without a dramatic increase in knowledge among developers about what options are available in terms of union models and a greater understanding on the part of existing unions about what developers need. Maybe it is trite to think that as democratic institutions, unions are what their members make them. In the meantime, developers will rely on the good will of their employers and the success of their games as they build their reputations and individual bargaining power. And we will all wait for the next powder keg to be posted online.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like