Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A Tale of Two Talent Trees

Can how skill trees or upgrade choices are presented affect how satisfied players will be and how likely they are to regret their decision?

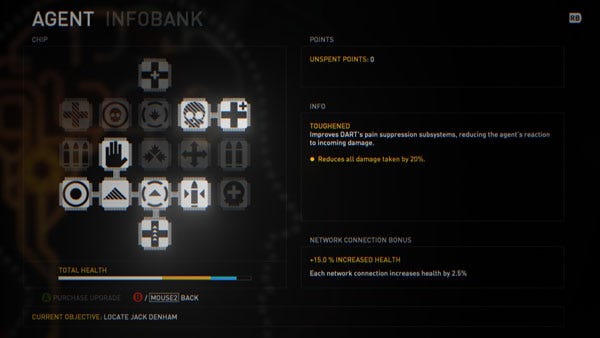

Can the presentation of choices on an upgrade screen or talent tree affect how we feel about those choices? Consider the two screenshots of talent trees below. No, look, don't ask why just yet. Just consider them!

The first one is from the first person shooter Syndicate while the second is from the latest Tomb Raider game. It may not be self evident from still screenshots, but these games handle the presentation of player choices differently. In the Syndicate tree, all your options are set out in one screen. Every time you have a skill point available you can mouse over any of those icons to get descriptions then choose the one you want. In Tomb Raider the choices are presented a little differently: you scroll from left to right through a sequence of skills at the bottom of the screen before deciding where to spend your precious point.

Which system, do you think, is more likely to result in commitment to and satisfaction with skill choices? Which do you think would be less likely to make players feel regret over their decisions and make them less likely to reload a saved game so they can make another choice?

A 2012 study by Cassie Mogilner, Baba Shiv, and Sheena Iyengar in the Journal of Consumer Research suggests that Syndicate's system would be better, based on the metrics of likely satisfaction, commitment, and regret. It comes down to hope for a better alternative and the way our brains tend to process the sequential versus simultaneous presentation of choices.

In one of their experiments the researchers had subjects review a list of 5 different chocolate treats, including a description for each one --e.g., "Waikiki: dark chocolate ganache with a blend of coconut, pineapple, and passion fruit". In one condition (the "simultaneous condition" or "Syndicate group" in my reckoning) all the chocolate names and descriptions were listed at once. In another condition (the "sequential condition" or the "Tomb Raider group") participants scrolled through the names and descriptions one at a time before making their choice. Subjects then got a free sample of the confection --YUM!-- and were told they were being entered into a lottery to win 25 more pieces.

Then, to get a feeling for how likely each group would be to abandon their choice right before going out the door, the experimenters offered to let them either change their lottery entry in favor of one of the other 4 chocolates they had seen, OR a mysterious sixth chocolate that they knew nothing about.

The results? Those who had seen their choices all at once were much more likely to stick with their original pick and rated their satisfaction with the choice much higher than those who were shown their choices sequentially. Those in the sequential group were twice as likely to switch their lottery entry to another chocolate, but the amazing thing is that they were almost four times as likely to switch it to the mystery chocolate.

The authors argue that invoking the emotion of hope in the sequential group is responsible for this finicky behavior and relative dissatisfaction with decisions. When we see all our possible choices, we know what we need to compare to what --it's all right there. When, however, we receive one choice at a time, we get into the mindset of comparing each option to an ideal or potential (but not certain) better choice. In other words, we hope that the next one is better. This, in turn, triggers feelings of dissatisfaction with each alternative and ultimately on whatever alternative we settle on. Those little dissatisfactions carry forward and make us more likely to abandon our choices if we're given a chance --especially for something that we think could satisfy our hope for something better.

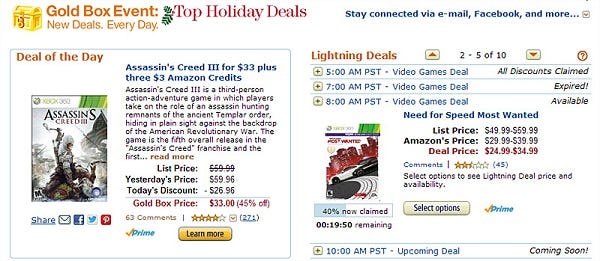

While we're on the topic, there's one other time when this sequential vs. simultaneous presentation comes to mind: Amazon.com's Lightning Deals vs. Steam's holiday sales. Amazon will sometimes queue up hourly deals that go on throughout the day. The catch is that they don't tell you what the hourly deals are going to be. This sounds to me like a sequential presentation of options for those of us without the funds to buy anything we want.

Compare that to the daily smorgasbord of deals that Steam dumps on you every day of their major sales events. Instead of a sequential list of deals that are dripped out, you get a fire hose of bargains all at once. Based on what I described above, which do you think would result in more satisfaction once consumers have made their choice?

Finally, game designers might look to hijack this effect and bend it to their own ends. Sometimes maybe they WANT to have players feel regret over a choice or have a feeling that things might have been better if they had made a different narrative or moral choice. In that case, designers might want to not offer all those choices in one menu or one dialog list. Maybe they would be better served by presenting them one by one and not giving players the option of backtracking. Little things matter.

REFERENCES

Mogilner, C., Shiv, B., Iyengar S. (2012). Eternal Quest for the Best: Sequential (vs. Simultaneous) Option Presentation Undermines Choice Commitment. Journal of Consumer Research, 39, 1300-1312. Did you find this kind of thing interesting? Wow, really? Well, you might want to follow me atwww.psychologyofgames.com or follow me on Twitter to see more.

Did you find this kind of thing interesting? Wow, really? Well, you might want to follow me atwww.psychologyofgames.com or follow me on Twitter to see more.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)