Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A Tale of Two PAXes

Iterating the exhibition - lessons from showing a small indie game at two consecutive PAXes.

(Reposted from my game development blog)

Before actually attending PAX Prime to exhibit Antihero last month, I’d already decided that this post’s opening line would be, “it was the best of shows, it was the worst of shows.”

This was naive. I’ve since learned that I’m constitutionally incompatible with conventions - there is no such thing as a convention I’m eager to attend, so there’ll never be a time when “it was the best of shows” will ring true.

But there are plenty of ways to make exhibiting more tolerable. So this post is about the delta between two PAXes, several months apart: what I observed, the mistakes I made on the first go-round, and the ways I tried to improve for the second.

(I understand and sympathize with just wanting to get on with making a game and skip all the bullshit of marketing and networking and whatnot. But I also feel like: this is the reality of any creative endeavor, and I’m going to suck it up and do these things - even though they’re uncomfortable and make demands on skills that I haven’t developed well - because I have some faith that it will occasionally open doors.)

Indie Minibooth

This past March, I’d come away from my freshman exhibitor experience at the Boston-based PAX East with a bunch of ideas about how to make my second show more successful and enjoyable. I’d been part of the “Indie Minibooth,” which is basically the kids’ table section of the Indie MEGABOOTH. The Megabooth is an organization that pulls together a bunch of indies into a common space - and under a common banner - on the PAX show floor, and the Minibooth is a small, high-density space within the Megabooth that gathers smaller games. It’s the smallest doll in the matroyshka of booths-within-booths-within-conventions.

The challenge of the Minibooth comes from the fact that it gathers so many games into such a small area. Because of this, there’s less opportunity for crazy booth design: all Minibooth games are shown at stand-up kiosks with small signs and Minibooth-provided monitors. You trade off customization opportunities for a turn-key exhibition setup: you just bring a game, and the location, setup, signage, and hardware is provided for you. Also, the Minibooth is probably the least expensive way to show at PAX.

Also worth mentioning is that the Megabooth has been around since 2012, which is practically forever ago in indie years, and the (tiny!) crew that runs “Indie MegaCorp” have done a wonderful job nurturing it. The Megabooth - and by extension the Minibooth - is a well-known entity, and its brand recognition is valuable. Showing at the Megabooth means that a member of the indie illuminati has decided your game is worth paying attention to.

In August, at PAX Prime, Antihero and I were back in the Minibooth again, which means that I can directly compare my strategies, successes, and failures in the two shows.

Exhaustion, Ego, & Melodrama

I was all by myself at PAX East, and that is something I hope never to repeat.

Conventions are physically taxing - you wake up at ungodly hours (7 AM!) for setup, you’re on your feet all day, it’s hard to find time to either consume or eliminate nutrition, etc. But more dramatically, showing your own work at a convention is just stupidly psychically draining. Like many introverts who’d rather hang out with a computer than with most other humans, I quickly get tired when I’m socializing with anyone who’s not a good friend. Being an exhibitor is all about hustling, which is perhaps the least pleasant of all social interactions, and having to hustle your own creation is like putting a physical manifestation of your ego in front of a bunch of randos and begging them to pass judgement on the last several years of your life.

So: the most impactful change I made from PAX East to Prime was to bring friends along. I’m a solo indie developer, so there are no coworkers to share the burden with, but several friends who are familiar with the game were kind/foolish enough to periodically tag me out on the show floor. (I told myself, beforehand, that I’d use my downtime to wander the Megabooth, check out what everyone else was doing, and make new friends. But actually, every time I had the opportunity, I’d just find a comfortable place to sit down, zone out, and restore some sanity.)

Having friends helping to exhibit also meant that I got to observe other people selling my game, which is useful and interesting because they have a more objective view of the thing, and the qualities they highlight and emphasize are frequently different from the ones I did. (An experiment I’d be interested in undertaking with like-minded indies at future shows is to swap booths with them for short amounts of time: I take notes on how to pitch your game and you take notes on mine. A live playtest of the convention experience.)

Iterating Spectacle: Attract Mode, Trading Cards, Cosplay

Show floors don’t select for good games - they select for spectacle. What I mean is, an important (the most important?) part of showing a game at a convention is simply getting people in the door, which has nothing to do with the game’s quality.

This is blindingly obvious in hindsight. I’ve attended conventions before. But it wasn’t until I was actually on the inside of a booth, competing against every other exhibitor for the attention of everyone who walked by, that it really hit home.

In order to fit so many games into a small space, some games in the Minibooth must face away from from the aisles where people are walking. At PAX East, I was lucky to have prime, outward-facing Minibooth real estate that I used poorly. The biggest issue was that the setup wasn’t eye-catching from a distance. Antihero is a turn-based strategy game with dark visuals; it doesn’t pop nearly as well as the most eye-catching games on the show floor.

One of my PAX East neighbors was One More Line by SMG Studio. These guys understood spectacle better than anyone else I saw at the show. “One More Line” is a one-button action game for phones. SMG was demoing it on the Minibooth-provided monitors, like everyone else - but since the game is played in portrait mode, their monitor was rotated 90°, which made it the slightly taller than other displays in the Minibooth. The game has clean, spare geometric visuals that look great in action and are visible from a distance. And most impressively, the O.M.L. booth had a perpetual line of people waiting to play - anyone who could get a high-score of 100 at the booth would win $100, word of which spread quickly and kept the line long. There is no better form of spectacle at a convention than a group of people gawking at something. People were far more likely to stop and check out Antihero if other con-goers were already playing.(1)

I took this to heart when planning my booth for PAX Prime: how to plan for spectacle within the constraints of the Minibooth (small space, standardized hardware, no custom signage).

The most important change I made was to the game itself: I added an attract mode. I’d originally planned to do this in-engine, by having two AI players compete against each other. Unsurprisingly, I didn’t have time to implement this, and ended up just having the game loop a slightly recut version of an existing teaser trailer after it had been idle for a short while. And though this decision was made due to time constraints, the video’s intercutting of game footage with punchy text and character closeups did a better job at quickly communicating the game’s theme and central hook (“run a thieves’ guild in a Dickens-inspired city”) than a purely in-engine version could have done.

Antihero wasn’t in an outward-facing kiosk at PAX Prime. I didn’t actually collect metrics (note to self: do this next time), but anecdotally, more people played the game than I’d gotten at East. The booth was usually occupied with multiple players (despite our small space, we could accommodate up to three players at once - two on iPads and one on the PC).

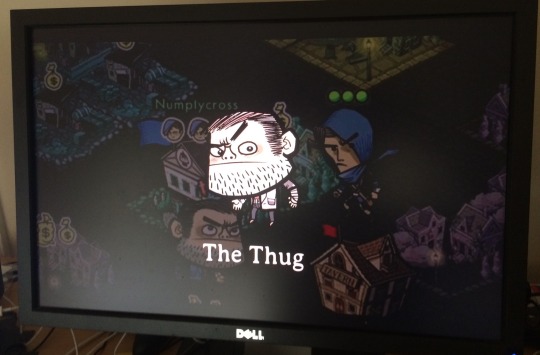

The next change was to the game’s promotional materials. At PAX East, I’d handed out dark flyers that were perfectly camouflaged by the black shelf that they sat upon. Few people noticed them unless I pointed them out, and I imagine they were quickly forgotten, by those who did take them, in the seas of undifferentiated swag that accumulate in the tote bags carried by every convention attendee. So for PAX Prime, I created trading cards showcasing the game’s various characters. The cards were bright, colorful, small, and sturdy. They didn’t look like other games’ promotional materials - they looked like little collectible artifacts. (In fact, they were simply rounded corner business cards from Moo.com, which allows you to use a bunch of different designs on a single batch of cards.) And they were a hit, with attendees eager to get their favorite character, or in many cases asking if they could take several or even a whole set (requests which were happily obliged).(2)

And finally, because custom signage wasn’t an option, I decided to abandon the jeans and hoodie I’d worn at PAX East in order to cosplay a character from my own game. Using clothes scrounged from Etsy, Goodwill, and the attics of various strangers’ grandparents, I played the Master Thief, and forced long-suffering friend and Antihero devblog maintainer Jack Shirai to dress as a street urchin. The idea was that the costumes could function as mobile signage, but really I think it just made us look more like hipster indies. Certainly nobody at the various evening indie boozefests batted an eye.

Pre-Promotion

I wish I had more to say about pre-promotion - the (dark?) art of securing press appointments in the run-up to a show. At PAX #1, I didn’t put much thought into this: I sent a handful of uninspired emails to a few press outlets that I recognized from the list that’s distributed to exhibitors several weeks before the show, and ended up doing a few very brief interviews on the show floor.

For PAX #2, I went through the entire press list and sent about 75 emails to various journalists and streamers. I followed a bunch of best-practices in the composition of these emails: I sent them as far in advance of the show as I could (within a day of receiving the press list), I used a clever (I thought) subject line and a short body that conveyed salient information about the game, I included a newly-cut trailer set to a catchy murder ballad, and I personalized each email. (In the cases where a large press outlet was sending multiple staff to the show, I spent time trying to figure out who best to direct my email to, based on the sorts of games they reviewed.)

And actually, the email response was pretty good. I got a number of nice replies from journos who were tickled by the email… and whose schedules were frequently “already fully booked.” I ended up, again, with very little press coverage.

Without more experience, I can only speculate about reasons for this. Of course, perhaps nobody thought the game looked interesting enough to talk about. Inconceivable! Ego aside, I don’t think this was the issue – if it does nothing else right, the game at least has an art style and theme that people respond to. (This wasn’t always the case - Antihero has undergone three major visual overhauls; the first two didn’t get many compliments.) Perhaps it’s too small a game? Maybe it doesn’t align well enough with gamers who are likely to read press coverage of PAX games? Maybe I should be reaching out to known press outlets even earlier, before the official list is distributed? Maybe it’s the indies who already have name recognition that get most of the press’s attention?

Anyway, it’s unclear to me. Further iteration of my press strategy is needed.

Final Thoughts

I do wish I enjoyed conventions, because I think they’re important. (I know there are indies who do; I’m jealous of those strange creatures.)

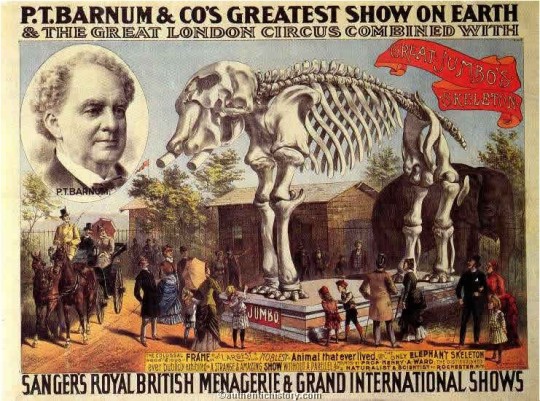

But I can, at least, imagine that cons get less exhausting with both practice and refined technique. Much of my fatigue came from dreading the response the game would get from the public, and the stress of trying to emulate PT Barnum, and feeling like a fraud, for 4 straight days.

(I’ve leaned heavily on melodrama here, which isn’t really my thing. But the revulsion I felt, the night before PAX Prime, for my incomplete, imperfect game - and for the idea of putting it in front of strangers - was so strong that I lay awake in bed, fantasizing about deleting every digital remnant of the thing from the world and going back home. I’m typing this out and it sounds ridiculous to me. This is not how I normally operate! But there you have it.)

Maybe - I hope! - you eventually get used to feeling fradulent, and then you no longer are.

I’m convinced that the resurgence of local multiplayer games among indie developers is due, in large part, to conventions and festivals. I have no idea if these games tend to be successful in the marketplace, but they are inherently festival-friendly – and therefore indie scene-friendly – in a way that few other games are.

The Assassin and the Urchin were the two female characters in the set of seven trading cards. They were easily the most popular; a number of women who visited the booth expressed happy surprise that their gender was represented in the game at all, which was wonderful to hear, and which also made me feel silly that the male:female character ratio is as lopsided as it is. I’ll be fixing this.

(If you’re interested in running your own thieves’ guild, you can read more about Antihero, my in-development game, or follow me on Twitter.)

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)