Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

“I want it just like LoL”: How do you monetize in-game skins?

Indie developers love repeating that they’ll never make pay-to-win games, nodding to League of Legends’ business model to justify their opinion. Is it really that easy to make money by selling visual content? And if so, how should one go about doing it?

These days, I’m in touch with budding indie developers every other day. After all, I was once one of them – having developed a number of close relationships with independent studios, I recently began considering indie projects for publishing with Pixonic. The question I ask each potential candidate is “How do you plan to monetize your game?”.

While the range of monetization options facing the creator of a new PvP game may be large, they can be divided into two fairly broad categories:

those that influence the player's chances of winning

those that don't give him any advantage over opponents

It's not hard to tell that this division is arbitrary – you can classify the options in different ways. This one, however, will serve this particular narrative best. For the sake of simplicity, let's label the first category "selling power" and the second "selling visuals".

"Our game won't have pay-to-win"

Returning to the question asked earlier, the answer I heard most often was – "Our game won't have pay-to-win". This reply – voiced by the most radical advocates of universal equality – probably means the following:

The amount of money the player invested in the game will have no influence on his progress or success. What matters are pure skill or luck – to each their own.

As our players are all equal before the game's laws, and our matchmaking abilities are next-level, our product will draw crowds seeking fair play, who will then buy visual content to support such an initiative.

While making these points, it's become customary to nod in the direction of League of Legends – one of the most successful games in history, where you can become a top player without paying a single dime. Riot Games' success with LoL has made it a benchmark – a beacon of sorts – guiding many developers in making their product.

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

In 2015, EEDAR, a specialist market research and data analysis firm, published a report containing a chart with MOBA microtransaction revenue shares. The chart confirmed the views of those looking to "sell visuals" – "cosmetic" products are an undeniable bestseller amongst successful MOBAs.

However, in 2014, Gamasutra released an article entitled "Don't Monetize Like the League of Legends" (which was naturally followed by a highly critical response). The author, Teut Weidemann, pointed to the unusually low conversion rate for a client-based game (3.75% vs. an average of 15-25% on PC), and accused Riot of apparently excessive methods in selling their new characters.

Releasing "overpowered" characters, so that a large number of players want to buy them straight after the updates, is fairly common practice in session-based PvP games – their qualities gradually even out (i.e. nerf) to a normal balance, matched by a drop in price. Is this coherent with the principles of fair play and eSports? As a general rule, such characters don't take part in competitions.

The doubts should be all but gone by now, surely? The case has everything going for it – a proven hit backed up by market analytics, as well as a positive perception of fair play amongst players. Why shouldn't one try and copy the LoL model and monetize visual content without "selling power"?

Survival bias

When we look at successful cases without taking into account those that came short, we become vulnerable to what is known as survival bias. Put simply – what if LoL's success occurred in spite of its monetization model, or was completely independent of it? Getting to the bottom of this question requires looking back at similar projects, of which there are quite a few.

Heroes of Newerth came out in 2010 and was very similar to DotA, only with greater complexity and a larger emphasis on creep farming at the beginning of a match. The game wasn't initially free to download, but S2 Games switched to the f2p model fairly quickly – about a year after its release. Despite a good start, HoN failed to carve out a niche for itself – its strong resemblance to DotA hurt the project, and the subsequent release of DotA 2 made player recruitment even harder. Not many people are aware of this, but the game is still alive, and while it's in the hands of different developers (Frostburn Studios), it can hardly be considered a flop. Looking back, you can say that HoN just managed get on board the train now being driven by LoL and DotA 2.

In 2013, EA released its own MOBA – Dawngate. The game had a number of differences from LoL, which led to the birth of a small following. Dawngate didn't make past its open beta, however – EA avoided going into too much detail, saying that the game "didn't meet its expectations", and that players would be compensated for their initial investments in the beta. Had the train already left by 2013?

The third case refers to the mobile market: for a long time, the MOBA genre was considered to be PC-specific, as it wasn't adaptable to a touch-based interface. There were many attempts to make the jump, which had varying degrees of success: Fates Forever, Call of Champions, Vainglory. For a while, it seemed that Vainglory was able to rethink the genre, having successfully made the transition to a mobile device. It was very quickly overthrown by Mobile Legends, which basically became the "mobile LoL" by copying its basic mechanics. What set it apart from its predecessors? Good controls, matchmaking and familiar mechanics.

The issues with "visuals"

Now that we have a little more information, we can say that the monetization model based on visual sales isn't a determining factor, a marker of success, or a kind of magic – it's just one of multiple possible ways of monetizing a game, and it doesn’t appear to have any particular advantages over “selling power”. Does it have any faults?

Plenty. The first and most obvious is the cost of production. Even if you’re bad at creating game balance, making a new animated character will always be longer/more expensive than adding new levels for old heroes. It’s possible to argue that visuals “sell” much better than boring numbers – this is only partially true. If a new hero sucks, this directly and negatively affects its sales. The hard work of artists and animators may well go to waste all because of these “boring numbers”.

The second drawback is increasing the size of the game client. When we introduced new skins to War Robots for Halloween-2016, we had serious concerns that the feature wouldn’t take off – useless camos could’ve become dead weight, eating up space on players’ devices and going unused. The build size is a very important factor for a game, as it impacts the number of installs. We ended up choosing a middle-of-the-road solution, warning our players that all purchased skins would disappear after a month and a half after their release (in fact, they would’ve been deleted only in the occurrence of critical issues, but we had to play it safe). Of course, this had a negative impact on skin sales - as soon as we removed the warning, players began buying them twice as often.

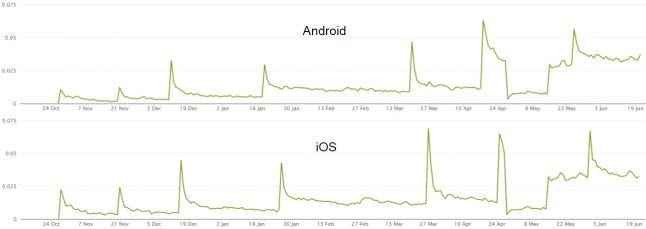

The third issue is diversity – the more in-game visual content you provide for your characters, the easier it is for players to personalize their heroes. As such, you need a lot of content. Here’s how the share of spent hard currency grew with each new pack of released War Robots skins (note that the “drop” in April-May isn’t a drop in sales, but an event that increased the total amount of spent currency, with no impact on skin sales).

A significant share of spending (around 4%) only appeared in April 2017, when the game already had 32 available skins.

Finally, the LoL model can’t possibly fit every game (in fairness, the same can be said about “selling power”). A character’s appearance will only matter to a someone if they know that a large number of players will see it. Personalization is also essential: it’s one thing if a player only changes the color of their clothes, but another thing entirely if you change the whole model, including animations.

To sum up, a game that plans to earn revenue primarily through the sale of visuals should have the following properties:

A huge gaming community / following

A large number of video streams, “memetic” gameplay

A competitive character, with a high degree of competition amongst players

Rich customization of visual appearance

Can a newly released game have all these qualities? Of course – for example, Playerunknown: Battlegrounds fits the description perfectly, all that’s left is for the developers to release new skins. While this may sound reassuring, do many indie projects “make it” like PUBG? Occasionally there’ll be a project or two, but they’re surrounded by the remnants of those that have tried and failed – the chosen model simply isn’t a sure-fire way of monetizing your game. Selling visual content is the icing on the cake – it can be a good addition to a game’s revenue stream, but it��’s just too risky to rely on if you want to make a bestseller.

A word of advice

Thoroughly test out the elasticity of demand for visual content. Customization is usually treated as a luxury good, which warrants the setting of high prices. War Robots’ experience indicates the opposite – the best-selling skin (by both amount and total expenses) in the game is the one bought for the first robot, at a price 10 times lower than that of any other skin.

Assess the cost of production. There are various degrees of depth to customization – from the sale of complete character visuals to individual costume elements, effects and animations. An understanding of your artists’ capabilities, as well as of players’ expectations, will help you choose what’s right for your product.

Keep the game setting in mind. We once decided to ask the War Robots community about what they thought about the following skin:

Only half of our players were willing to put up with a massive battle robot looking like a stick of candy floss – the “cuteness” didn’t go down well. This helped us understand the audience’s expectations, and the skin never made it into the game.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)