Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

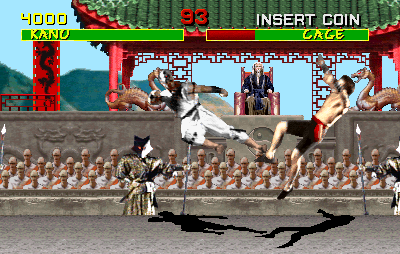

This extract from Tristan Donovan's comprehensive history of the game industry covers the early '90s tumult in the U.S. caused by violent games, with Senator Joe Lieberman going after Mortal Kombat and Night Trap.

[Gamasutra is pleased to present an excerpt from Tristan Donovan's new and extremely comprehensive book, Replay: The History of Video Games, which is available now in the U.S. and UK. This extract covers the early '90s tumult in the U.S. caused by violent games -- with Senator Joe Lieberman going after Mortal Kombat and Night Trap.]

On Wednesday 1st December 1994, the Washington press corps gathered for a press conference called by Joseph Lieberman, the Democrat Senator for Connecticut. Next to Lieberman on the stage was Bob Keeshan, aka Captain Kangaroo -- the USA's favorite Saturday morning kids' TV presenter.

Once the assorted reporters had taken their seats, they were shown footage from two of the latest video games to reach the market. In one scene a digital image of an actor playing a martial arts fighter ripped the still-beating heart out of his opponent's chest.

The next scene showed film footage of a young woman in a nightdress being dragged off-camera by vampires before the sound of a high-pitched drill being used to extract the victim's blood is heard.

The games in question were Mortal Kombat and Night Trap, and, like many adults in the U.S. at the time, most of the people in the room were unaware of these games, let alone their gory content.

"We're not talking Pac-Man or Space Invaders anymore," Lieberman told the stunned journalists. "We're talking about video games that glorify violence and teach children to enjoy inflicting the most gruesome forms of cruelty imaginable."

Captain Kangaroo told reporters he could "not believe anybody could go that far" and said the nation's children were being exposed to such material in the name of greed. "Violent video games may become the Cabbage Patch dolls of the 1993 holiday season," Lieberman added. "But Cabbage Patch dolls never oozed blood and kids weren't taught to rip off their heads." Video game makers were in the dock facing charges of corrupting the nation's children.

Mortal Kombat

The industry had, of course, been here before. There were the bomb threats that followed the hit-and-run driving game Death Race, the outrage over the pornographic Custer's Revenge, and the 1985 protests about the release of Raid Over Moscow in the UK.

"In Raid Over Moscow you had to break through and bomb the Kremlin," said Geoff Brown, founder of the game's UK publisher US Gold. "It was number one in the charts, hundreds of thousands of copies being sold to kids and CND took it upon themselves to picket our offices.[1] I thought it was fantastic. I mean how could it get any better? It was in every newspaper. They were there every day. We used to give them coffee and they used to walk around with banners like 'ban the bomb'. I kept saying you'll be better off if you didn't keep coming here, it would actually sell less."

But in late 1994 the game industry wasn't laughing off the outrage. There had been a growing sense that the video game industry would eventually end up facing the wrath of Washington's politicians and the early 1990s had already seen some minor skirmishes with lawmakers.

In June 1990 a Democratic Party member of the California Assembly called Sally Tanner tabled a law to ban games that featured alcohol or tobacco. Among the games under threat of being outlawed was Roberta Williams' 1987 children's nursery rhyme-themed game Mixed-Up Mother Goose, which featured a pipe-smoking Old King Cole. The game industry managed to get the law dropped after pointing out that Tanner's application of the ban to video games and not other media was unfair.

Tobacco had also caused another headache for the game business in January 1990 when controversy erupted about Sega's arcade racing games Hang-On and Super Monaco GP. Unknown to tobacco manufacturers, both featured barely disguised adverts for cigarette brands such as Marlboro, which the game's developers had included because it was in keeping with the tobacco-dominated advertising boards that adorned racetracks at the time.

When the row broke, tobacco companies such as Philip Morris threatened to sue, conscious of being accused of trying to peddle cigarettes to children as a result. Sega agreed to remove them.

But the intervention of Lieberman and Captain Kangaroo took video game controversy to a whole new level. Lieberman openly declared that what he really wanted was an outright ban, although the US constitution would probably not allow it. Instead he, together with fellow Democrat Senator Herbert Kohl, organized a public inquiry to investigate the problem of violent games and called some of the leading lights of the game business to appear before it for questioning.

---

[1] CND, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, were a UK pressure group. Raid Over Moscow also caused controversy in Finland, where a member of the country's parliament prompted a debate about whether its sale should be allowed.

The events that led to the Senate's inquiry began back in 1991 when artist John Tobias and programmer Ed Boon, who worked for Chicago-based arcade game manufacturer Midway, started thinking about their next project. Street Fighter II had just become the biggest arcade hit for years and Midway wanted a fighting game of its own. "We were fans of head-to-head arcade games and their appeal to the arcade crowd," said Tobias. "I was also a huge geek for Hong Kong martial arts cinema and was looking for an excuse to use some of those influences."

Having agreed to create Midway's answer to Street Fighter II, the pair started debating how they could make their game -- Mortal Kombat -- stand out from Capcom's landmark game. "A big goal of mine was to differentiate the visual qualities of Mortal Kombat from any of the other 'fighting' products out there. It was important for players to look at Mortal Kombat and know immediately that it was, at the very least, different," said Tobias.

The arcades were already overflowing with fighting games and some arcade owners were already tiring of them.

"We purchased fighting games when they first came out, but after a while we stopped buying them," said Bob Lawton, founder of New Hampshire arcade Funspot. "The sequels were coming out at a pace we couldn't keep up with and as soon as a new version was released, no-one wanted to play the older one."

Tobias hit on the idea of using digitized footage of real-life actors, an approach that had already been used in a small number of coin-op games, such as Williams' Narc and Atari Games' fighting game Pit-Fighter.

"We thought that by using the digitizing technique we could achieve a high level of detail, given the size of the on-screen characters in an expedited amount of time," he explained. The team hired actors to play out the roles of their virtual fighters in the game and, after some touching up, imported their images into the game.

Aside from the digitized characters, Mortal Kombat did not stray far from the Street Fighter II formula, sticking to Capcom's combination of secret moves, two-player action, and tactical brawling. Until they started testing it, that is. "There was an anti-climactic moment at the end that created the opportunity to do something cool," said Tobias. "We wanted to put a big exclamation point at the end by letting the winner really rub his victory in the face of the loser. Once we saw the player reaction, the fact that they enjoyed it and were having fun, we knew it was a good idea."

The "exclamation points" Tobias and Boon came up with were a selection of gory takedowns that could be enacted using secret button and joystick combinations when the game urges the player to "finish" their defeated opponent. Tobias and Boon called these gruesome finishing moves "Fatalities". "We certainly weren't out to cause controversy. We were out to serve the needs of our players and make sure that they enjoyed themselves while playing -- that was our number one goal all of the time," said Tobias.

And enjoy themselves they did. Mortal Kombat became the hottest game in the arcades since Street Fighter II, as players fought each other in the hope of delivering a brutal fatality move to their crushed opponent. With Mortal Kombat taking the arcades by storm it was only a matter of time before it arrived on the home consoles.

Acclaim Entertainment snapped up the rights and converted the game to both the Sega Genesis and Super NES. Sega approved the game complete with the violence from the arcade original, but Nintendo was more squeamish and insisted the fatalities were removed. Acclaim told the Japanese giant that the fatalities were the selling point and removing them would give Sega the superior game. Nintendo refused to change its mind and Acclaim grudgingly cut the gore from the Super NES edition.

With the home console versions of Midway's arcade smash ready, Acclaim prepared one of the biggest game launches ever seen at that point. The company declared that the launch day, Monday 13th September 1993, was "Mortal Monday" and lavished $10 million on TV advertising to ram home Mortal Kombat's arrival in U.S. homes.

Children and teenagers across the nation were inspired to start urging their parents to buy them a copy. One of them was the nine-year-old son of Bill Anderson, the chief of staff for Lieberman. Anderson was shocked at the violence in the game and told Lieberman about his son's request for a copy. Lieberman decided to check it out for himself. He too was shocked at a game that he saw as rewarding players for violent acts. He delved further into the video games on sale in the shops and found Night Trap, one of the first games released on CD-ROM.

Night Trap began life back in the late 1980s as part of Axlon and Hasbro's abandoned VHS videocassette console, the NEMO. After the NEMO project collapsed, Axlon co-founder Tom Zito managed to recover the rights to the game and formed a development studio called Digital Pictures to bring the game out on the Sega CD, an add-on for the Sega Genesis that hosted some of the first games to be released on compact disc.

The goal of the game was to protect a group of teenage girls at a slumber party by setting traps for vampires. Lieberman felt the scenes where the partygoers were dragged off by the vampires were sexist; particularly a scene where a woman dressed in a nightgown is attacked in the bathroom.

After finding out that most console owners were under 16 and that most of the parents in Connecticut who he spoke to knew nothing about the content of the video games their children played, he decided to act. The violent games Lieberman had homed in on were exceptions, but they justified the unease about video games that many parents felt. It was a distrust that reflected the historical pattern of new forms of media or entertainment being viewed -- at least initially -- with suspicion.

Such reactions to new forms of media could be seen in Greek philosopher Plato's criticisms of theatre and Hollywood's "sin city" image during the late 1920s and 1930s. As British psychologist Dr Tanya Byron noted in 'Safer Children in a Digital World', her 2008 report for the UK government: "The current debates on the 'harms' of video games and the internet are the latest manifestations of a long tradition of concerns relating to the introduction of many new forms of media."

It was a suspicion that had even caused games such as Lemmings, a 1991 puzzle game created by Scottish game studio DMA Design, to face criticism. The game was a play on the popular myth that the rodents regularly commit mass suicide by jumping off cliffs. It charged players with trying to save the creatures by leading them to safety while bouncy renditions of tunes such as "How Much Is That Doggy in the Window?" played in the background.

But the inclusion of levels where the lemmings had to avoid rivers of lava and negotiate volcanic rocks before jumping into the fiery mouth of a demon to escape prompted one southern U.S. TV station to call for the game to be banned for its satanic imagery.

But such criticism was not just about video games. The early 1990s were a time when fears about violence in society were particularly high on the U.S. political agenda. Congress was debating whether to restrict violent TV programming and a new gun control law, the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, was about to be signed into law by President Bill Clinton.

Other nations also shared America's unease about Mortal Kombat. Germany's youth media watchdog the Bundesprüfstelle für Jugendgefährdende Medien banned the game outright in 1994 for its extreme violence. Until then the only games outlawed in this way were a bunch of free neo-Nazi propaganda games that started circulating around Germany and Austria at the end of the 1980s. [2]

---

[2] These racist and anti-Semitic games were not released commercially, but distributed for free and, apparently, quite widely. One newspaper poll of Austrian students reported that 22 per cent of students had encountered these games, which included concentration camp management games and quizzes testing how Aryan the player was. The Bundesprüfstelle für Jugendgefährdende Medien banned seven such games between 1987 and 1990.

The first day of the Senate inquiry into video games was set to take place on the 9th December 1993, just eight days after Liberman's press conference with Captain Kangaroo. Ahead of the hearings Nintendo, Sega and the other video game publishers in the firing line suddenly realized just how poorly connected they were in Washington, D.C. While many of them belonged to the Software Publishers' Association, its focus was on supporting business software companies such as Lotus and Microsoft rather than video game publishers.

Under fire: Senator Joseph Lieberman wields a gun controller during the Senate inquiry into video game violence (AP Photo / John Duricka)

With the political pressure mounting, Sega and Nintendo found themselves forced together to try and come up with a strategy for tackling the hearings. The two harbored conflicting views of what should happen.

Sega, with its more teenage audience, wanted an age rating system so it could carry on publishing games featuring violence. Nintendo, on the other hand, saw little need for an age rating system as it had its own family friendly policies that it applied to all games released on its console.

But with the pressure on, the U.S.'s leading game companies agreed to back an age-rating system that would be managed by the industry itself in the hope of defusing the row.

This opening gambit took some of the heat out of the situation, but the proponents of video game restrictions at the hearings still tried their best to land some blows on the game makers. Marilyn Droz, vice-president of the National Coalition on Television Violence, asked senators how they would feel if their teenage daughter went on a date with someone who had just played Night Trap.

Eugene Provenzo, the University of Miami professor who had already annoyed the game business with his critical 1991 book Video Kids: Making Sense of Nintendo, also made the case for intervention. Drawing on his research, Provenzo told the hearings that 40 of the 47 games he examined for his book were violent. Video games were also "overwhelmingly" racist, sexist, and violent, he added.

There was some truth in Provenzo's claim. Female and black video game heroes were a rarity and this absence was still pronounced years later as a 2001 report by US children's charity Children Now discovered. Children Now's report revealed that women accounted for just 16 per cent of playable human characters in the 10 most popular games of 2000. It also reported that 58 per cent of playable male characters were white, but that if they had excluded sports games the proportion would have been much higher.

"Video games do seem to do worse than other mediums, particularly when it comes to the representation of women," said Patti Miller, director of the charity's children and the media program. "The lack of racial diversity in video games seems to be on a similar level to that of U.S. TV."

It wasn't just a matter of ignoring women and black people. A few Japanese games had descended into racist stereotyping of black people, partly because the country's more homogenous racial make-up meant such racism was rarely confronted.

For example, the 1989 role-playing game Square's Tom Sawyer, based -- somewhat ironically -- on the Mark Twain's novel The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, portrayed black characters as blackface-style caricatures with giant lips. It was never released outside Japan.

Many Japanese games did, however, seek to avoid portrayals of race altogether, through the use of "mukokuseki" characters that are drawn in such a way to obscure their racial origin, so that while they could viewed as white or Asian, but were neither.

In the West the racism in video games was more subtle and behind-closed-doors, with some game publishers pushing designers to "whiten" the skin tone of black characters or remove them entirely. "It all boils down to money," Shahid Ahmad, a British Asian game developer, told Edge magazine in 2002. "Publishers believe that games with black or Asian characters could lose them money, although they won't openly say it."

Homosexuality, meanwhile, remained largely taboo in video games throughout the 1980s beyond Japan's yaoi, or boys' love, titles. The few that did mention the subject usually did so in a negative way. It took until the 1995 adventure game The Orion Conspiracy for the subject to be tackled in a less prejudiced way. Created by UK developer Divide by Zero and published by Domark, The Orion Conspiracy cast the player as a father who travels to a space station to investigate the death of his son.

While searching for the truth, it emerges that the son was gay. "When I first read the script I was quite surprised," said "Tardie", an artist who worked on the game. "It was a very daring thing for Domark to do. The gay character was embedded into the game and you found out about it as you questioned people and discovered more about your son. It got quite charged as the father did not know, so you got to see how he handled it."

The real battle in the Senate on the day of the hearing, however, was not between the proponents and opponents of restrictions on video games but between Sega and Nintendo. It did not take long for the bitterness between the two video game giants to bubble to the surface and soon Washington's finest were watching Nintendo of America chairman Howard Lincoln and Sega of America vice-president Bill White Jr. engaged in their own verbal equivalent of Mortal Kombat.

Lincoln used Nintendo's earlier decision to force Acclaim to remove the gore from the Super NES version of Mortal Kombat as a stick to beat its commercial rival with. He said Nintendo had lost money by sanitizing its version of Mortal Kombat and had even received angry letters and telephone calls from children demanding the violence before proudly adding that Night Trap would "never appear on a Nintendo system", ignoring how the lack of a CD drive meant the Super NES was technologically incapable of handling such a game.

White countered that Sega had an older audience demographic to Nintendo, a claim echoing the underlying message of his company's "Sega does what Nintendon't" advertising campaign: Sega is for cool teens, Nintendo is for children.

He added that Sega had already introduced age ratings on its games voluntarily and that it wanted other companies to adopt its system.

Lincoln stuck the knife in. He dismissed Sega's age ratings system as a panic measure introduced when the controversy about Night Trap started and refuted White's assertions that the video game industry was now catering for adults rather than children.

White started listing the violent games available on the Super NES and showed the Senators a Nintendo light gun. Lincoln described Night Trap as "outrageous".

White defended it by pointing out that the player has to try and stop the vampires only to get slapped down by Lieberman who interjected: "You're going to have to go a long way to convince me that that game has any moral value." Lieberman watched the pair tearing chunks out of each other with amazement.

Nintendo and Sega weren't the only people in the games business divided by the controversy. The game developers who worked on Mortal Kombat and Night Trap were also divided over how to react to the row their creations had started.

"I felt like we were being attacked by a bunch of people who were mostly ignorant of what they were attacking," said Tobias. "Watching the news coverage at the time, you'd think that Mortal Kombat was created by some evil corporation. Anyone who knew me or Ed personally knew that our intentions weren't anything other than ensuring our players were having fun."

Night Trap

Rob Fulop, who had designed Night Trap while it was still part of Hasbro's NEMO project, found the experience harder. "The scandal was kind of silly and it was also deeply embarrassing because friends of mine, my parents, and my girlfriend didn't really get games. All they knew was a game that I had made was on TV and Captain Kangaroo said it was bad for kids," he said. "I fell out with my girlfriend because I thought it was completely bullshit."

But while he thought the inquiry was nonsense, after nearly 15 years of game making, Fulop had begun to worry about the message video games were sending out to children. "I grew up in a generation where you watched TV, that's all we did. TV was basically 30-minute stories and always had a happy ending. Whatever the problem, in half an hour the problem was worked out," said Fulop.

"You tell that story to kids 20 million times and they grow up believing everything will work out. That was my generation. You believed everything would work out because of TV. Now think of video games -- the message is no matter what you do you always lose. You never ever, ever, ever, ever win. Once in a million you win, but most of the time you never win. Unless you can find the cheat, so what does that teach you? I think that's created a whole different culture -- a very fatalistic 'what's the point?' attitude. It's a personal philosophy, I don't know if it's true or not."

The controversy surrounding Night Trap and the reaction of his family and friends inspired Fulop's next game: "I decided that the next game I made was going to be so cute and so adorable that no-one could ever, ever say it was bad for kids. It was sarcastic. It was like what's the cutest thing I could make? What's the most sissy game I could turn out?"

A shopping mall Santa Claus gave him the answer. "I would go at the end of the year to see Santa Claus at the stores and he would tell me exactly what kids wanted," said Fulop. "He knows better than anyone because his job all day is to ask them what they want. You want to know what's going to sell, go talk to Santa. I did that every year. I went that year and he said the same thing that was popular every year was a puppy and has been for the last 50 years."

Fulop's plan to make an adorable game and children's Christmas wishes for puppies came together to form 1995's Dogz: Your Computer Pet, one of the first virtual pet games. [3]

Dogz installed an enthusiastic cartoon puppy on the player's computer that was housed within a playpen window but could be stroked or taught to do tricks.

Fulop's goal was to make players grow attached to their virtual puppy: "The dogs follow your mouse and they can't wait to be petted, you do a mouse click and they come running over, it was their biggest excitement.

"People get attached to pets because they need you. You're needed. You come home and this thing is in your face... if you're not there you know it's going to be very unhappy or it could die. I don't think a virtual pet is any different."

Fulop's company PF Magic played on this attachment to encourage sales of the game. "It was sold the same way real puppies are sold," said Fulop. "We'll give it to you for 10 days and then ask for it back. You give a puppy to a kid and ask for it back five days later -- see what he says. In sales this is called the 'puppy dog close'.

"We gave you five days' worth of food and after five days you ran out of food and if you want more food you've got to call us and give us $20 and we'll give you a lifetime's supply of food, otherwise your puppy dies or you have to delete it. And who can delete it? It's cruel, it's a little puppy and you won't feed it."

Fulop's ploy worked like a dream and Dogz became a huge success, eventually becoming the starting point of the long-running Petz series of virtual pets.

* * *

With evidence about the relationship between video game violence and real-life behavior inconclusive, the senators closed the hearing by telling the video game industry to return to Washington on 4th March 1994 to report on its progress with creating an age rating system. [4]

In the three months between the hearings and the industry's return to the Senate, the U.S. video game industry reorganized itself. The country's leading game companies quit the Software Publishers Association and formed the Interactive Digital Software Association headed by veteran Washington lobbyist Douglas Lowenstein.

After several weeks of rows, the industry also created the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB). The ESRB's job was to manage the industry's new age-ratings system. Sega also stopped distributing the Sega CD version of Night Trap in January, although America's leading toy stores Toys R Us and Kay-Bee Toys had already stopped stocking it because of the Senate hearings. [5] The changes were enough to satisfy the Senate. The controversy was laid to rest and Lieberman and Kohl's threats of creating a state-run regulator with it.

The game industry came out of the controversy with more than just a lesson in how to handle politicians. It had also learned that violence and controversy sells. Sales of Mortal Kombat and Night Trap soared during the hearings.

Night Trap in particular had gone from a poorly selling Sega CD title to a game that was selling 50,000 copies a week at the height of the row. When Zito's Digital Pictures released Night Trap on the PC to coincide Halloween 1994, its advertising campaign embraced the scandal: "Some members of Congress tried to ban Night Trap for being sexist and offensive to women (Hey. They ought to know)."

Arcade game maker Strata, which also got a ticking off in the hearings, stuck its middle finger up to Washington within months of the hearings by launching BloodStorm, a Mortal Kombat clone featuring even more extreme violence and a hidden character that had Lieberman's head so players could beat up the Democrat Senator.

Lieberman's attempt to challenge video game violence failed. If anything the changes that resulted from his intervention made video game violence more acceptable, as the age ratings system would identify violent or controversial games as for adults, not children, helping game publishers defend themselves against future accusations of peddling violence to children.

And with an age ratings system in place Nintendo no longer felt compelled to filter out the violence from games released on its consoles. When Acclaim launched Mortal Kombat II on the Super NES, the fatalities and blood remained in place. "The inquiry didn't impact anything," said Tobias. "We were content with the M for mature on our packaging. Developers and publishers fell in line, accepted the ratings system and developed games according to the need of the product."

The Senate hearings had actually made it safer for video game developers to create violent games, not harder.

---

[3] Bandai's portable virtual pet the Tamagotchi came out shortly after Dogz in 1996. Created by Aki Maita, the electronic toy became a global sensation similar in scale to the Rubik's Cube. Tens of millions were sold worldwide.

[4] The evidence is still inconclusive. As Bryon's 2008 report for the UK government noted: "It would not be accurate to say that there is no evidence of harm but, equally, it is not appropriate to conclude that there is evidence of no harm." She added: "The research evidence for the beneficial effects of games is no more convincing than the work on harmful effects."

[5] The bigger selling Mortal Kombat, however, remained on sale.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like