Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

The History of a Forgotten Computer : PART 2

This is the true story of how one if the first home computers came to be. And the small group of people who created the software for the system. This is part of our history and a story I hope everyone will enjoy. Part 2 of 2

The History of a Forgotten Computer : The CyberVision

PART 2 of 2

The first article I ever wrote for Gamasutra was entitled, "A Brief History of Videogame Development." That article had a brief look into a story about a group of early game developers. That short story of mine piqued interest in a number of people who asked me to pursue this fascinating tale further. And so I did, and here you have it.

This is a two part story about one of the very first home computers ever created. In the first part I told the story of how on one rainy evening John and Joe happened across the people who created the hardware for the CyberVision and how that weekend and the nights following John and Joe wrote an operating system and some demo software for a presentation to Montgomery Ward. The presentation to Montgomery Ward was successful and the CyberVision 2001 was scheduled to be sold through Montgomery Ward. John and Joe's company ARI was contracted to create the software for the CyberVision. In the first part of this story I wrote about how the team at ARI created the software for the CyberVision which was a very different process than how it is done today.

If you haven't read it yet, you can find the first part here:

http://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/MattPowers/951858/

The year was 1977. That year and the following years were monumental in the history of computers. And with this story you are reading just one of the many stories about some early pioneers in our computer industry.

Thank you for reading my article and I hope you enjoy this look into some of our video game history that was pretty much unknown, until now.

- Matt Powers.

PART 2 - The future that just wasn't to be...

I was a software developer for the CyberVision 2001 from its inception to its demise. My business partner and I developed its operating system and, with the rest of our software development team, all of the nearly 30 applications for the CyberVision. We have CyberVisions in the attic; the last time we checked, they still worked. We also have copies of all the applications that were developed.

- John Powers from a 2010 posting on: http://www.armchairarcade.com/neo/node/3400

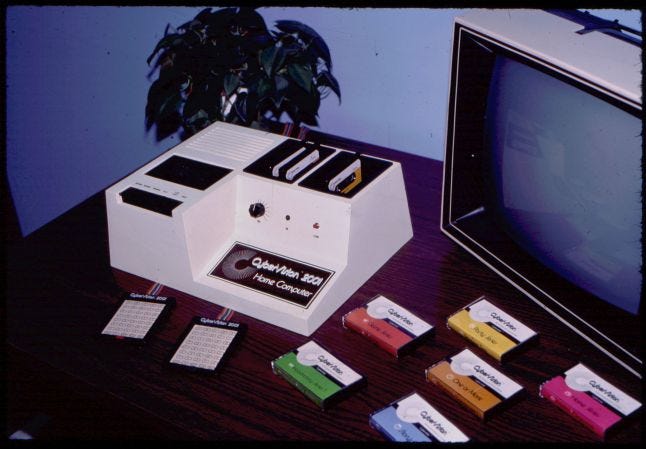

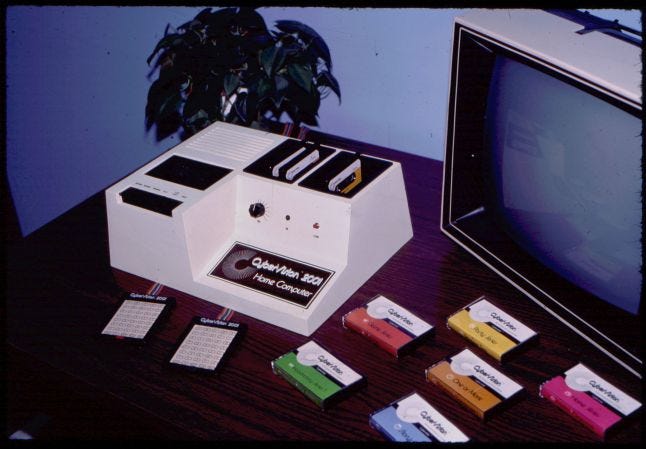

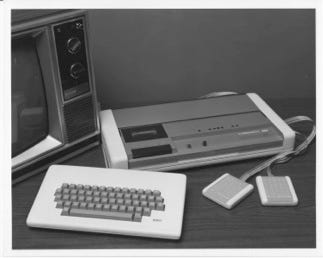

CyberVision 2001 with Cybersettes

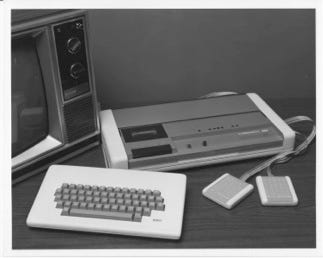

I was John's business partner and co-founder of the company that developed the CyberVision 2001 (3001, and 4001), and I can tell you that the product was released and sold nationally by Montgomery Ward in 1978. We had an order from Ward's for 10,000 units of the initial product configuration (pictured in the Ditlea book) that we fulfilled, and a new form-factor (model 3001) was released on a second round of orders from Wards. We also developed a prototype of a much sleeker looking 4001 model, which included an extended adaptation of Ron Cenker's floating point BASIC in ROM. That model was never manufactured in quantity.

- Joe Miller from a 2010 posting on: http://www.armchairarcade.com/neo/node/3400

CyberVision 3001

Until the end, ARI continued to innovate and improve upon their designs. There was a CyberVision 4001 that did not see the light of day. As Joe Miller recalls:

We only built one of these but it had full backward compatibility with a previous tape, plus an internal integer-only BASIC interpreter, and a full-featured floating point BASIC on an external ROM cartridge. It also had a full size qwerty keyboard, as an option to the two 40-key keypads. I still have it and it still works. - Joe Miller

CyberVision 4001

An Insider's View

One of the key members of the people upstairs that night John and Joe went looking for their CompuColor 8001 was John McMullin. McMullin was a business man and the CyberVision was one of the many startup businesses he was involved with. In early 1977, John McMullin had a meeting with John and Joe to discuss the future of CyberVision and ARI. In the office during that meeting was one of John McMullin's employees - Ken Balthaser. Ken worked for McMullin selling TV production services. Ken had no sales background but came from a background of broadcasting and audio/video production.

Soon after CyberVision was kicked off, McMullin moved his offices closer to the offices of ARI. And that meant Ken was able to more easily visit ARI. Ken had seen the future and wanted to be a part of it. His current position had him making cold sales calls pitching to corporate customers. But Ken had heard the plan for this new computer and started bugging ARI to hire him. And ARI did hire Ken. I asked Ken to give his memories and perspectives on ARI and CyberVision. And he provided a great insight into what it was like in those days.

The Ken Balthaser Story

The following section was written by Ken Balthaser

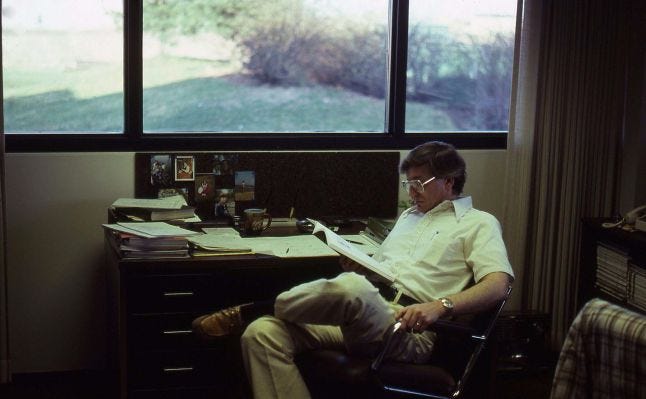

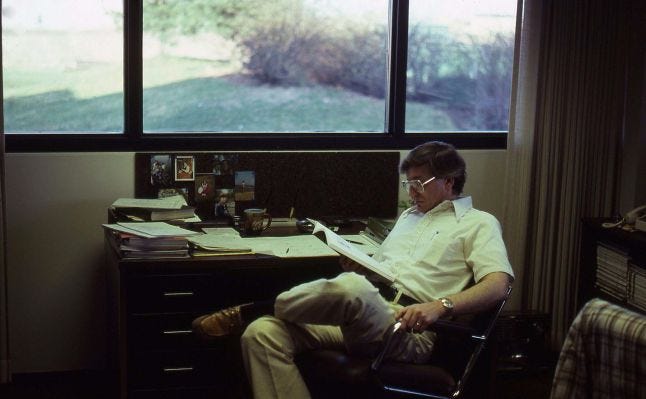

Ken Balthaser at ARI

Very soon after starting at ARI, I became fascinated with computer programming. John and Joe were big influence on that. I really admired those two and what they could do with code, and I wanted to learn how to do it. I started out by writing BASIC programs on that Wang computer in the office. It was on that system that I learned logic, code design, debugging, etc. Later, I self-taught myself how to program in the RCA 1802 assembly language with much help (and great patience) from both Joe and John. They were wonderful mentors and taught me a professional way of coding with well designed code and thorough code documentation. By the end, I was actually writing subroutines that were being used in some of the apps. By that time I was totally hooked on programming.

One of the things to remember is that this whole time was the embryonic period of the personal computer industry. There were no tools. No graphics or animation tools. This was way before Photoshop and other tools. So, everybody had to invent tools to implement their programs. We had no desktop computers, no monitors. We wrote our code on a DecWriter printer, printing out our code on perforated reams of paper. No deleting, no copy and paste. There wasn't even an operating system for our COSMAC development system. It used 8” (maybe they were 10” ) floppy discs and we used a lined piece of paper with numbers for each line. These numbers represented the track numbers on the floppy disc. Each person using the system would find consecutive tracks available on a disc, write their code out to those tracks and then, using a pencil, write in which tracks were used. When they no longer needed those tracks, they would erase their entries so that the next person could use them. It was very primitive, but it worked.

My single technical contribution, sort of, was the A5 synching system that we used. The CyberVision system used an off-the-shelf stereo cassette tape player for the data and soundtracks. The data was recorded on one track and the audio was recorded on the other. The system would load the data and begin executing the code while the audio played. A problem arose because there were slight differences in the motor speed for each tape deck. This meant that if a deck played back a little bit faster or slower then, after time the audio would get out of synch with the code.

That's when my experience in slide/sound productions came in handy. Multiple slide projectors were kept in synch or triggered to a sound track by using audio blips that would trigger the control box to change slides. I mentioned it to Joe as a possible solution to the synch problem. After some thought, he came up with a solution based on that type of system - A5's. The hexadecimal number A5 produces a unique series of bits as ones and zeros. By stringing a series of these A5's together the system would monitor the data track and “listen” for this unique series of bits. When it detected them, the computer would execute different commands such as stop tape, start tape, fast forward tape, etc.

Fast forwarding was another stroke of genius because this allowed code branching. This seems obvious and easy to do today with a gazillion gigabytes of RAM into which to load your code. But, back in 1977 the CyberVision had just 2K of RAM to work with. That meant, for example, if your code was 16K in size and you had just 2K to store it, you had to do something with the other 14K of code. Well, it was stored on the tape and loaded as needed. Brilliant!

Recording a cassette tape in our office that would work on the CyberVision computer was one thing. Creating thousands of tapes of that same program was an entirely different matter. Recording tapes one at a time in the office was not an option. Imagine recording a twenty minute tape in real time and doing it ten thousand times. Not gonna happen. So, we needed mass production. We found a company in St. Louis that did mass audio cassette duplication.

Maritz was a mass producer of audio cassettes. They did production for some of the largest companies who were producing audio cassettes for education, entertainment, audio books, But, they had never duplicated audio/digital cassettes. I made several trips to Maritz to oversee the duplication and test the cassettes as they came off the recorders. The first batches of test tapes were a disaster. None of them worked when put in our CyberVision computer. What the heck was going on? Our engineer, Jim McConnell, flew out and analyzed the cassettes on an oscilloscope. It turned out that high-speed tape duplication changes the phase of the audio by 90 degrees. CyberVision did not like this. The audio portion of the tape was fine. Our ears don't care about such things. But, the hardware, reading the analog portion representing the digital code, got confused. So, Jim devised some hardware that would distort the phase of the analog signal on a master cassette so that when it went through the high-speed duplication the phase shift was compensated for. We went through many iterations tweaking the amount of phase shift until we found the one that worked. Then, we went into mass duplication. This was a harrowing time because if we couldn't solve the phase shift problem then we would have been effectively dead in the water. Many kudos go to Jim McConnell for solving this and many other technical problems.

What I remember most are the people, the CyberVision crew. We were a small group of just 8 people that pulled it off. Everybody was nice and nice to each other. Even through the most stressful and difficult times everybody was encouraging and supportive. We all got along with each other. And, there seemed to be a genuine love, not only of the work we were doing, but love for each other. And, that's what made the end of it all so devastating.

Perhaps if we had been in Silicon Valley from the beginning it would have ended differently. Maybe if we had been funded by Kleiner Perkins instead of the Pioneer Coal Company things would have panned out for us. Possibly if Montgomery Ward had had a true electronics department in which to sell the system instead of the sporting goods department, we might have fared better. And, we had manufacturing problems from the start by an incompetent Pennsylvania company whose main business was assembling military gear. It was probably a combination of all of these things that ended it.

The competitive battlefield of consumer electronics is littered with hardware and CyberVision was just one of the legion of companies that rolled onto that field: Video Brain, Bally, Fairchild, Magnavox, Commodore, Texas Instruments, Tandy, Mattel, Coleco, Atari and many others. They all fought the good fight but in the end they all ended up in garages, warehouses, second hand stores, garbage dumps and sometimes buried in vast pits in an Arizona desert. But, that's the nature of a new industry. Just look at any new industry that shapes the future and you'll see the same, whether it's cars, televisions, aircraft or computers.

When it ended, John P. was the only one who had the sense to fly to California where all things computer were really happening. The rest of us just sort of stumbled around in a daze. There, in the heart of a young and burgeoning Silicon Valley, he landed a gig heading up software for Atari's newly formed Personal Computer System division. Then, one by one, he brought the heart of the CyberVision crew to Atari and that was the beginning of a whole lot of new stories which you might be told sometime, if you are very, very good.

Thanks Ken. And now back to the writing of Matt Powers....

Brief Timeline

A quick timeline of the history of ARI and CyberVision:

John and Joe had the first meeting with John McMullin and Jim McConnell on (a Thursday) 7/14/77, at 894 W. Broad St. (This was the day they came looking for the color terminal for the Qube project.) John McMullin pitched the "crash" project, but he didn't agree to business terms until Sat., 7/16. (ARI offered to do the work at a 50% discount off our normal hourly charge-out rates.)

John and Joe started work in earnest on the OS/Monitor ROM on Saturday, 7/16, and they didn't stop that weekend until Monday morning.

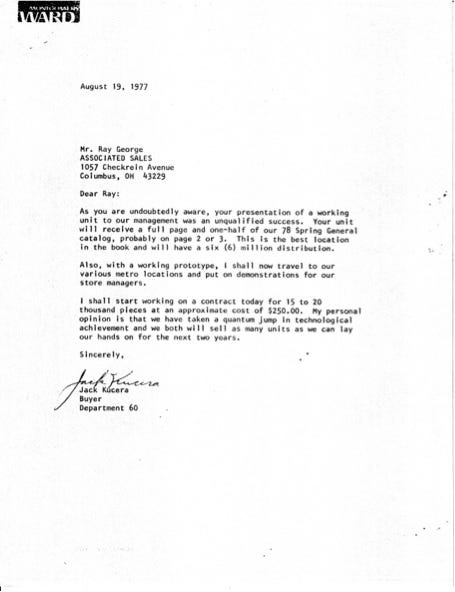

They first met with Ray George on 7/21; on 7/22 they started working (around the clock) out of his office on Checkrein Ave. which was right around the corner from the ARI offices. (Ray was manufacturing and selling an exercise bungee cord out of those offices...)

Joe proposed the name "CyberVision" for the product on 8/10 and on 8/12 (a Friday) John and Joe got on a plane to Chicago with a completed Operating System in ROM and three demo tapes. On the strength of that demo, they had a verbal commitment from Ward's to place an order and give their system pages 2 & 3 of the Ward's Spring General catalog for 1978.

On Monday, 8/15/77, Joe hand-carried the ROM image to an RCA plant in New Jersey to start the manufacturing process. At that point, the ROM was "locked" in for the initial units, less than 30 days from that initial mysterious meeting on Broad St. To that date, John and Joe had expended over 615 man-hours on the project, pretty much consuming all their waking hours, at the expense of other ARI projects and customers.

Ironically, and foreshadowing much of what came later, it took the group until 10/25/77 to actually be paid for any of this work.

The first CyberVision units at physical Wards stores were first available on 6/2/78, and 8 of 10 units were sold on that first day.

Like the Sands of the Hourglass

In 1976 Atari released Atari Pong. The Magnavox Odyssey 300 was also released in 1976. In 1977 Atari released the VCS (later called the VCS 2600). In 1979 came Intellivision and 1982 was Colecovision. 1985 saw the release of the Nintendo Entertainment System. Squeezed in the middle was the release of the CyberVision 2001.

Montgomery War ad for the CyberVision 2001

In 1978 the CyberVision was available to shoppers at Montgomery Ward for $399. Also at that time:

Philips introduced the video laser disc (aka laserdisc and LD).

The Radio Shack Tandy computer was available to purchase for $399.

Grease (1978) continued the explosion of rock-music hit films (after Saturday Night Fever (1977)) - again featuring super-star John Travolta.

Bally/Midway releases the Bally Professional Arcade home console.

Taito Corporation releases Tomohiro Nishikado's arcade game Space Invaders in Japan. The worldwide success of Space Invaders marks the beginning of the golden age of arcade video games.

The history of the CyberVision is brief and mostly forgotten. But, as with all the early computers of that time, the impact is something that shouldn't be forgotten. In the case of the CyberVision, it was not the machine itself that carried ripples through the industry but the employees of ARI that went on to greater things. A brief overview of where the ARI employees went from there:

Joe Miller - Executive at Sega, Epyx, and VP of Linden Research, creators of Second Life. He's now the VP of Engineering at SportVision.

Brenda Laurel - Co-founded Purple Moon, featured on the cover of Wired Magazine to commemorate her involvement in girl gaming, and author of multiple books on design and technology.

Janey Powers - After the CyberVision, Janey returned to her original career in educational marketing. She later transitioned into financial marketing and became a Vice President of a large Bay Area financial institution and a judge for the Marketing Association of California.

Jeff Schwamberger - Senior User Experience Consultant at companies such as Hewlett-Packard, Smartleaf, Verisign, Microsoft, Macromedia, and more.

John Powers - Executive at companies such as Atari, The Learning Company and Convergent Technologies; Senior Software Engineer at Apple and founder of a number of start-up companies including Poohbah Industries (www.poohbah.com). 35 years after CyberVision, partnered with Ken Balthaser to create a game for the iPhone and iPad called Star Trux. John's son, Rob, was the artist.

Ken Balthaser - Executive at Epyx Games, Sega, MicroProse and currently founder and President of Balthaser Online.

This group of employees from ARI has stayed in touch over the years. And, they still try to get together for a "company" BBQ at least once a year. They were nicknamed the "Ohio Mafia". Sometimes at these get-togethers a CyberVision Shrine is set up and people reminisce about those "crazy good 'ole days." I'm looking forward to the next reunion which is coming up this very month of May.

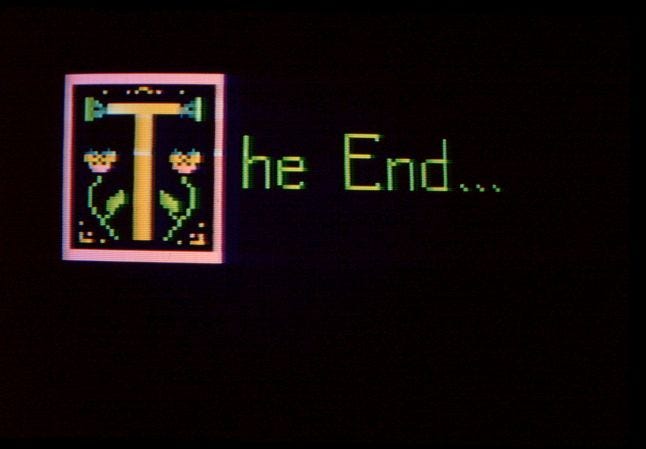

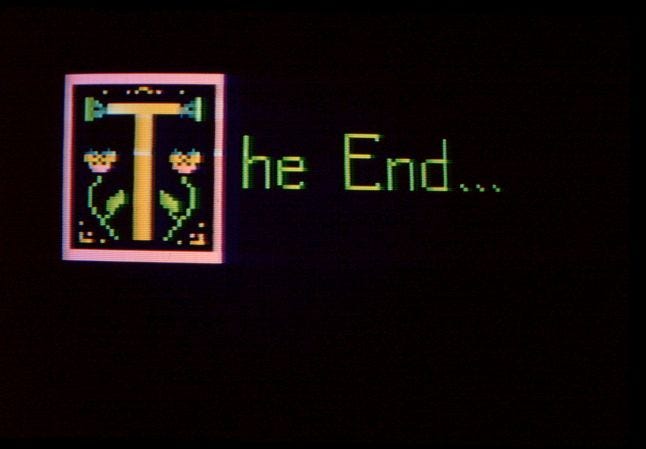

End screen from "Goldilocks and the Three Bears" on the CyberVision

Some Final Thoughts from the Author

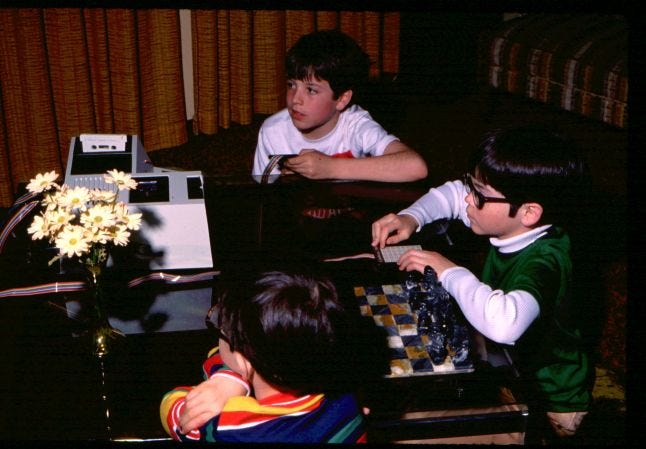

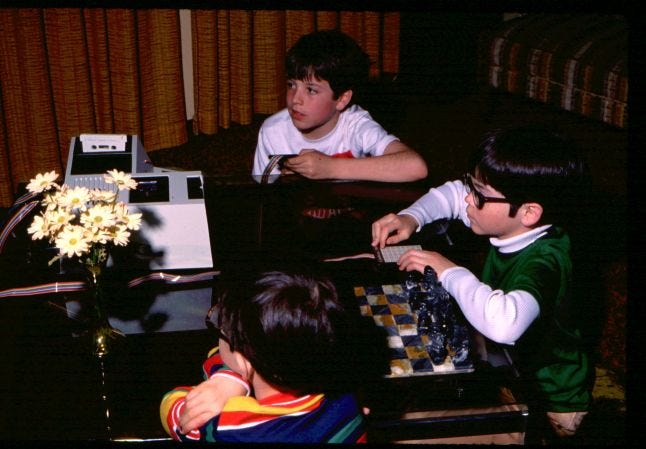

One of the reasons I wanted to write this story was because of my memories of being involved in the story.

The author (top center) and his brothers playing with the CyberVision

I still remember playing the CyberVision as well as remembering when my family moved to California once the CyberVision stopped being sold and ARI closed their doors. And while that move from Ohio was drastic, it turned out great as my Dad was working at Atari. I remember visiting the Atari offices to see and play the latest games. My Dad would bring home EPROMS of the newest games for myself and my brothers to play. And, I definitely remember my Dad teaching me to program. That programming experience led me to start working at a video game startup after college in 1993. This was with my friend Neil Balthaser, son of Ken Balthaser (my Dad's friend from ARI).

Over 20 years after my Dad, Joe, Ken, and others started ARI and started making some of the first computer games, Neil and I were at our own startup making games. And 20 more years after that, I am still in the video game business.

About the Author

Matt Powers has been making video games for over 20 years. Matt feels that recognizing and remembering our history and what came before us is important as we look to our future. Currently Matt is looking for new opportunities in the San Francisco Bay Area.

If you liked this article or have any questions about it please leave a comment. For more articles written by Matt Powers you can visit:

http://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/MattPowers/951858/

If you would like to contact Matt: [email protected]

Special thanks to the Ohio Mafia without whom this story would not be possible.

Thanks and references from:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Read-only_memory

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)