Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Past, Present and Future of Music and Audio in VR

This article presents an historical overview of the 3D audio tech promising to be a vital part of virtual reality game design - from its early incarnations and tumultuous history, to promising trends for future development in music & sound for VR.

In this blog, I thought we might take a quick look at the development of the three dimensional audio technologies that promise to be a vital part of music and sound for a virtual reality video game experience.

In this blog, I thought we might take a quick look at the development of the three dimensional audio technologies that promise to be a vital part of music and sound for a virtual reality video game experience.

Starting from its earliest incarnations, we'll follow 3D audio through the fits and starts that it endured through its tumultuous history. We'll trace its development to the current state of affairs, and we'll even try to imagine what may be coming in the future!

But first, let's start at the beginning:

3D Audio of the Past

In the 1930s, English engineer and inventor Alan Blumlein invented a process of audio recording that involved a pair of microphones that were coincident (i.e. placed closely together to capture a sound source). Blumlein's intent was to accurately reflect the directional position of the sounds being recorded, thus attaining a result that conveyed spatial relationships in a more faithful way. In reality, Blumlein had invented what we now call stereo, but the inventor himself referred to his technique as "binaural sound." As we know, stereo has been an extremely successful format, but the fully realized concept of "binaural sound" would not come to fruition until much later.

In the 1930s, English engineer and inventor Alan Blumlein invented a process of audio recording that involved a pair of microphones that were coincident (i.e. placed closely together to capture a sound source). Blumlein's intent was to accurately reflect the directional position of the sounds being recorded, thus attaining a result that conveyed spatial relationships in a more faithful way. In reality, Blumlein had invented what we now call stereo, but the inventor himself referred to his technique as "binaural sound." As we know, stereo has been an extremely successful format, but the fully realized concept of "binaural sound" would not come to fruition until much later.

Beginning in the late 1960s, spatialization in sound recording made a big leap ahead with a technology called ambisonics. Writes Hugh Robjohns for Sound on Sound Magazine,"The format was developed using complex mathematics and psychoacoustics, all based on the original work on coincident stereo led by Alan Blumlein in the early 1930s."

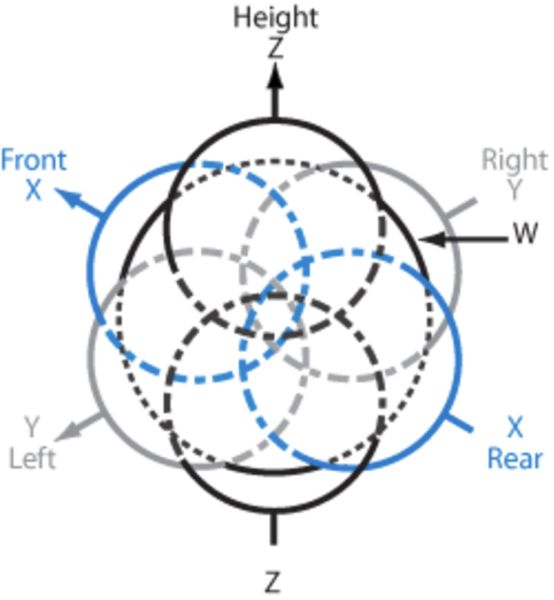

Developed in the UK by physicist Peter Fellget and mathematician Michael Gerzon, the ambisonics technology allowed sound to be recorded with both horizontal and vertical spatial positioning. In other words, the sound could wrap itself around the listener like a sphere, delivering audio content from top to bottom. To the right is pictured a visual representation of the spatial audio content captured by the ambisonic recording technique. Despite the effectiveness of the technology, ambisonics found little commercial success.

Developed in the UK by physicist Peter Fellget and mathematician Michael Gerzon, the ambisonics technology allowed sound to be recorded with both horizontal and vertical spatial positioning. In other words, the sound could wrap itself around the listener like a sphere, delivering audio content from top to bottom. To the right is pictured a visual representation of the spatial audio content captured by the ambisonic recording technique. Despite the effectiveness of the technology, ambisonics found little commercial success.

Meanwhile, the binaural recording method was also finding it very difficult to gain traction with the public. Since incorrectly used by Alan Blumlein, the term 'binaural' had come into frequent use by record companies when describing stereo recordings that were in no way binaural. In order to best fit the definition of a binaural recording, a two-channel sound source must mimic the timing and intensity differences that would typically be encountered by human ears.

By virtue of the subtle shades of difference between the sounds detected by our right and left ears, we are able to pinpoint the location of those sounds in our environment. A binaural recording method employs two microphones spaced to mimic the positions of human ears, and those microphones may also be mounted inside a dummy head (such as the one pictured right), the microphones positioned within modeled ear canals to precisely duplicate the physiology of human hearing. Here's an awesome video produced by The Verge about the science of binaural recordings:

By virtue of the subtle shades of difference between the sounds detected by our right and left ears, we are able to pinpoint the location of those sounds in our environment. A binaural recording method employs two microphones spaced to mimic the positions of human ears, and those microphones may also be mounted inside a dummy head (such as the one pictured right), the microphones positioned within modeled ear canals to precisely duplicate the physiology of human hearing. Here's an awesome video produced by The Verge about the science of binaural recordings:

While binaural has been around for quite awhile, it failed to become popular with the public, and like ambisonics, binaural floundered in obscurity. Meanwhile, surround sound became famous as the de facto standard for spatial positioning in audio. However, surround sound never had the capability to account for height when assigning positions to sound sources. In essence, the audio environment in a surround sound mix would encircle the listener in a horizontal ring - the sonic equivalent of a hula hoop.

That brings us to 1996, when Aureal Semiconductor released a new soundcard for PCs called A3D. This soundcard seemed to herald a rebirth of true spatial positioning and three dimensional sound. The technology was so revolutionary that Maximum PC Magazine hailed it in 2007 as one of the greatest 100 PC innovations of all time. The sound card was at its most impressive in gaming applications, wherein it could calculate the size of the 3D environment and accurately determine sound reflections based on in-game surfaces. Like binaural recordings, the A3D sound card also employed head-related transfer functions (HRTF) for the right and left speakers, incorporating timing and volume intensity differences that would normally occur between the right and left ears when hearing a sound from a particular point in space. This video is a technology demonstration from 1998, showcasing the power of Aureal A3D:

That brings us to 1996, when Aureal Semiconductor released a new soundcard for PCs called A3D. This soundcard seemed to herald a rebirth of true spatial positioning and three dimensional sound. The technology was so revolutionary that Maximum PC Magazine hailed it in 2007 as one of the greatest 100 PC innovations of all time. The sound card was at its most impressive in gaming applications, wherein it could calculate the size of the 3D environment and accurately determine sound reflections based on in-game surfaces. Like binaural recordings, the A3D sound card also employed head-related transfer functions (HRTF) for the right and left speakers, incorporating timing and volume intensity differences that would normally occur between the right and left ears when hearing a sound from a particular point in space. This video is a technology demonstration from 1998, showcasing the power of Aureal A3D:

A3D might have been a resounding success, if it were not for the patent infringement suit leveled against Aureal Semiconductor by its closest competitor, Creative Labs. In the end, Aureal won the lawsuit, but the costs of litigation bankrupted them, and Creative Labs subsequently bought Aureal and buried the A3D technology.

In the same year that Aureal Semiconductor released A3D, Microsoft released DirectSound3D - a software component bundled with the DirectX collection of protocols and tools for the Windows operating system. DirectSound3D allowed for the spatial positioning of audio content in three dimensions, and it also included Doppler shift for moving sound sources to indicate proximity, as well as timing and volume intensity differences based on location. DirectSound3D offered the chance for developers to work with a standardized interface for the creation of 3D sound across multiple types of PC soundcards. Also, DirectSound3D enabled the PC hardware to bear some of the computational burden incurred by such a complex 3D sound system. Despite all these advantages, Microsoft discontinued DirectSound3D in 2007 when Windows Vista was released. Here's a demonstration of DirectSound3D in the Far Cry video game:

In the same year that Aureal Semiconductor released A3D, Microsoft released DirectSound3D - a software component bundled with the DirectX collection of protocols and tools for the Windows operating system. DirectSound3D allowed for the spatial positioning of audio content in three dimensions, and it also included Doppler shift for moving sound sources to indicate proximity, as well as timing and volume intensity differences based on location. DirectSound3D offered the chance for developers to work with a standardized interface for the creation of 3D sound across multiple types of PC soundcards. Also, DirectSound3D enabled the PC hardware to bear some of the computational burden incurred by such a complex 3D sound system. Despite all these advantages, Microsoft discontinued DirectSound3D in 2007 when Windows Vista was released. Here's a demonstration of DirectSound3D in the Far Cry video game:

After the demise of DirectSound3D, the art of spatial positioning in audio stagnated. "The fact is that for many years, software implementations in games generally fell flat because they didn’t compute the array of computations needed to create truly 3D audio," writes Mark Chase for Maximum PC. "For the better part of a decade, 3D audio backpedaled, stumbling to regain its footing as software alternatives fumbled to fill the void."

So that brings us to the present. How have things changed?

3D Audio of the Present

The coming virtual reality revolution has rekindled many of the 3D audio technologies that had floundered in obscurity for so long. For instance, the binaural technique of sound recording is currently experiencing a full-blown renaissance. "Binaural audio is able to recreate a sound field so the listener feels like they were actually there when the recording was made," writes Samit Sarkar of the video game news site Polygon. "Binaural audio does for sound what virtual reality does for visuals."

Oculus is bringing binaural audio to virtual reality by licensing VisiSonic's RealSpace3D binaural audio engine for incorporation into its Oculus Audio Software Development Kit (SDK) for the Oculus Rift (pictured right). Mark Chase of Maximum PC points out, "the tech relies heavily on custom HRTFs to recreate accurate spatialization over headphones, the same principle Aureal pushed nearly two decades ago." So the long-dead A3D technology is also getting to see new life via the Oculus Rift.

Oculus is bringing binaural audio to virtual reality by licensing VisiSonic's RealSpace3D binaural audio engine for incorporation into its Oculus Audio Software Development Kit (SDK) for the Oculus Rift (pictured right). Mark Chase of Maximum PC points out, "the tech relies heavily on custom HRTFs to recreate accurate spatialization over headphones, the same principle Aureal pushed nearly two decades ago." So the long-dead A3D technology is also getting to see new life via the Oculus Rift.

When wearing a VR headset, our experience depends on the virtual world responding to our head movements precisely. This responsiveness must transfer to the audio side of things as well. "Head tracking is also one of the key reasons truly 3D audio is so critical," Chase writes. "In real life, we often pinpoint sounds by moving our head slightly, rotating or cocking it while our brain notes the sonic discrepancies."

While binaural audio is achieving deserved recognition as a preferred format for VR audio mixes, the long-neglected ambisonics format is currently being seriously considered as an alternative to binaural recording techniques for virtual reality applications. Capturing audio using ambisonic microphones is fundamentally different from recording that same audio material with a binaural "dummy head." An ambisonic microphone (such as the TetraMic pictured left) is essentially a group of four microphones that each capture differing aural data. One captures sound pressure, while the other three record the spatial coordinates of the sounds being captured. This is much more flexible than the binaural recording method, because it allows the "sphere of sound" around you to shift realistically as you move through it, while the audio captured by the ambisonic recording technique adjusts depending on your relative position.

While binaural audio is achieving deserved recognition as a preferred format for VR audio mixes, the long-neglected ambisonics format is currently being seriously considered as an alternative to binaural recording techniques for virtual reality applications. Capturing audio using ambisonic microphones is fundamentally different from recording that same audio material with a binaural "dummy head." An ambisonic microphone (such as the TetraMic pictured left) is essentially a group of four microphones that each capture differing aural data. One captures sound pressure, while the other three record the spatial coordinates of the sounds being captured. This is much more flexible than the binaural recording method, because it allows the "sphere of sound" around you to shift realistically as you move through it, while the audio captured by the ambisonic recording technique adjusts depending on your relative position.

"Even if you didn’t originally capture your sound ambisonically, you can still use the ambisonic format to encode your fancily-produced spatial sound information as a sphere of sound," writes Vi Hart of the eleVR Virtual Reality Research Group, adding that one might simply "apply a rotation to match the head tracking, then collapse it into binaural stereo."

The Future of VR Audio?

If Vi Hart's last statement sounded a bit speculative, there's a reason for that. "It all seems so easy," writes Hart, "perhaps too easy, to implement basic ambisonics, that I’m surprised I haven’t seen it done yet." Then Hart adds, "Just how well will this theory work in practice? I don’t know!"

The future of virtual reality audio looks like it will be an exciting frontier for game audio folks to explore. Meanwhile, those adventurers at the leading edge of the frontier are encouraging innovation in some ambitious ways. Oculus is currently giving away its RealSpace3D binaural audio engine for free, for use on any platform. Meanwhile the 3DCeption Spatial Workstation has integrated the ambisonic format into its tools for mixing the aural environment of a virtual reality experience. It should be interesting to see how these audio technologies enhance the immersive environment of a VR game!

So that's the end of this brief tour of the past, present and future of VR audio. I hope you've enjoyed this blog, and I encourage you to share your thoughts, questions and ideas in the comments section below!

Winifred Phillips is an award-winning video game music composer whose most recent project is the triple-A first person shooter Homefront: The Revolution. Her credits include five of the most famous and popular franchises in video gaming: Assassin’s Creed, LittleBigPlanet, Total War, God of War, and The Sims. She is the author of the award-winning bestseller A COMPOSER'S GUIDE TO GAME MUSIC, published by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press. As a VR game music expert, she writes frequently on the future of music in virtual reality video games.

Winifred Phillips is an award-winning video game music composer whose most recent project is the triple-A first person shooter Homefront: The Revolution. Her credits include five of the most famous and popular franchises in video gaming: Assassin’s Creed, LittleBigPlanet, Total War, God of War, and The Sims. She is the author of the award-winning bestseller A COMPOSER'S GUIDE TO GAME MUSIC, published by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press. As a VR game music expert, she writes frequently on the future of music in virtual reality video games.

Follow her on Twitter @winphillips.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)