Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Masafumi Takada is possibly the breakout Japanese game composer of recent years - soundtracking cult titles Killer7 and No More Heroes and contributing to the Smash Bros and Resident Evil series - Gamasutra goes in-depth with him on his art.

"I don't consider myself, or want to become, an artist; instead, I want to be a craftsman."

One of Japan's major video game composers, Masafumi Takada may have the musical chops to match the work of his colleague at cult Japanese developer Grasshopper Manufacture, Suda51, whose recent No More Heroes features a sizzling (and apparently very Audiosurf-able!) soundtrack Takada created - delivering the crucial aural component of Grasshopper's "video game band" ethos.

But Takada's modesty and dedication speaks to a more traditional work ethic. Working even without a studio on Grasshopper Manufacture's premises, he strives to create memorable musical compositions that evoke emotion in the player, also shown in his work for Killer7.

Outside his Grasshopper work, Takada has been landing surprisingly high-profile work, including contributing music to games like Super Smash Bros Brawl, God Hand, and Resident Evil: The Umbrella Chronicles - and also provided music for Earth Defense Force 2017 and the Beatmania series.

In the most in-depth English-language interview of Takada's career, the musician discusses working with Goichi Suda, the company's innovative music-based combat game Samurai Champloo, and much more.

Where did you learn music, and what instruments are you trained on?

Masafumi Takada: I started learning music at age 3 on a keyboard called the Electone. It was an organ-like keyboard from Yamaha. So I learned piano, and tuba in the brass band after that, when I was in high school. I'm from Aichi, which is near Nagoya. When I came to Tokyo, I started studying music for about six years, and got a degree.

And how did you get into games from there?

MT: I wanted to make a living doing music... and right around that time the transition from the Super Famicom (SNES) to the PlayStation was going on. Music was changing from the blippy chiptune sounds to real music. And I really liked video games a lot, and basically just had some hope to eventually write music for games, and that transition seemed like a good time to break in.

Did you actually start with chiptunes, like Super Famicom type stuff? Or did you go straight into orchestrated music?

MT: When I entered the industry, it was sort of the end of the Super Famicom, so I did a bit of that, but was also able to sample the higher-end stuff. That's why I got in when I did...

Can you name some of the early games that you've worked on?

MT: Hmm, I didn't really work on any major titles in the old days! First there was 2Tax Gold on Sega Saturn [by now-defunct developer/publisher Human]. That's the game where my name was actually shown in the credits. I also worked on Ranma 1/2, and Tsuri Baka Nisshi, a Japanese manga-related fishing game.

MT: Hmm, I didn't really work on any major titles in the old days! First there was 2Tax Gold on Sega Saturn [by now-defunct developer/publisher Human]. That's the game where my name was actually shown in the credits. I also worked on Ranma 1/2, and Tsuri Baka Nisshi, a Japanese manga-related fishing game.

What sort of music do you listen to, personally?

MT: Hmm. Right now I'm listening to the Pirates of the Caribbean soundtrack. Also I'm listening to something I used to listen to when I was high school, a guy named Haruomi Hosono. He was part of Yellow Magic Orchestra. But I'm really not listening to that much music right now!

Oh really? Where do you draw inspiration from?

MT: Well when I have to work on new music for a new title, I do look for a bit of inspiration, but since I don't right now... not so much.

Can you give an example of some things you listened to that turned into some sort of inspiration?

MT: Well for example the boss fights in No More Heroes were inspired by the Chemical Brothers' new album.

Are there other game composers that you admire, or just composers in general?

MT: In terms of classical, there's Debussy. And otherwise, Ryuichi Sakamoto.

Do you do sound effects as well, and sound design?

MT: Yes, I do.

On average how long does it take for you to compose music for a game?

MT: Well, it varies. There are some that took a while, and...

A couple of examples, maybe?

MT: For Killer7 it took two years. But in the mean time I had a lot of little projects so... Hmm... I'm pretty fast at writing music, so basically, even when I come into the office, sometimes half of my time is spent on my music work and half of my time is spent on personal work (laughs). If possible, I want to finish one song in one day.

And how long for sound design?

MT: As for sound effects, because all together there are a lot... I often work on a game from beginning to end, but in terms of sound design, there are other audio staff members in addition to me, so we can divide up the work. So it takes about four months or so to complete.

How large is the audio team size?

MT: Right now there are four people.

And do you have a sound studio here? Like a foley room and stuff?

MT: No. I do everything at my desk. Even if you don't go all the way to a studio, if you have a microphone and a tape recorder you can recreate sound effects anywhere, like this [Takada demonstrates at his desk].

So here, in this office?

MT: Here, after everyone leaves and goes home.

Do you do your own audio testing, here? Or do you have testers actually check the audio?

MT: Of course I consult others too; me and other audio staff members. Also when the rest of our staff on the floor plays the game, I quietly observe their reactions. If they jump and are surprised by certain parts, then I know it's a success.

The reason I ask is because some audio designers that I know feel that the only thing that normal testers can tell you is whether the sound is present. They can't tell you if it's the feeling that you were trying to get across, or even if it's the correct sound. That's why you'd create a map of what it's supposed to be like, and then they can look at this thing and understand how it's supposed to be.

MT: Hmm, first off, I just have to reach the point where I myself think, "Good. This is okay." If you feel something different about the audio in the Grasshopper games, it's probably because the audio department is on the floor where everyone else is -- together with the graphic, project management, planning and programming departments, so the audio staff is producing work in an environment where they can easily communicate with the rest of the production team. That can take the project in a good direction.

I thought there was very good music implementation in Grasshopper's Samurai Champloo game, because the beats of the attack combos were actually based on the music. With that music, how was it to write music for a series that already had very established, very interesting music style?

MT: The soundtrack for [the anime] Samurai Champloo was very good. I really like it myself. I don't mean to say I felt in competition with the original soundtrack, but to tell you the truth I didn't want to lose against it.

Namco Bandai/Grasshopper Manufacture's Samurai Champloo: Sidetracked

Did you get to speak to [anime series composer] Tsutchie at all?

MT: No, I didn't talk to him... I just listened to it.

I see. How faithful did you feel you had to be to the original sound style?

MT: Actually I wanted to use the anime BGM for the game, too. I thought the fans might prefer that. But it seemed the licensing would be far too difficult. So yes, I had to create an original soundtrack. It was really hard, actually, because it was the first time I ever attempted any sort of hip-hop.

Well, in some ways it seems like it was a natural fit for you, because it's kind of hip-hop and also kind of lounge-style, and you have a whole lot of lounge style in existing games that you've done.

MT: As far as my own style is concerned, I can't say I understand what it is, myself. I mean, I really want to try lots of different genres.

How much do you think music actually affects gameplay and the user experience?

MT: When you play video games, the game space is just what's on the front of the TV. But the rest of the space in your environment, the whole area around you, is completed by the sound. When games are built from the beginning, they're made without sound. And when you add the music and the sound, you're giving life to the game.

So in a way you're creating the bridge between the user and the television, by filling the world around them? How then do you work to connect the player on the outside to the game that's just on the TV surface?

MT: I think about this a lot. Music is really tied to your experiences and memories, similar to how your sense of smell is. If you hear music that you've heard before, it should bring memories from that previous time rushing back. So the game is of course a virtual world, where there are naturally things that don't have any relation to reality.

But perhaps these experiences could happen to you in the future. The music will be tied to these potential future experiences. So I want to create music that will tie you to, and remind you of, the virtual world, but also come back to you in the real world, and create future memories. The soundtrack should recall your old memories, but also help forge new ones.

After you've played the game, when you listen to just the music, I want players to be able to remember the feelings they had at that time, and their feelings of that era.

A lot of people seem to create soundtracks that are very much in the background. But as you mentioned, there are soundtracks where you recall where you were and what you were doing at the time that you played that game. Most people don't make distinct themes anymore.

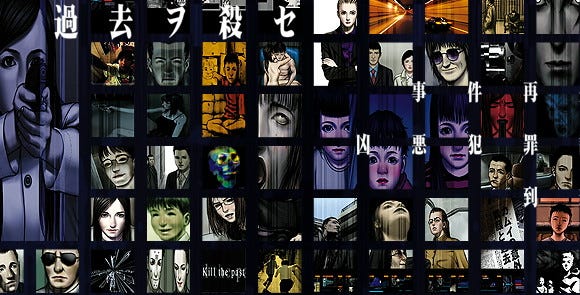

You can remember Super Mario, you can remember Castlevania, you can remember Zelda, but for the last 15 years you can't remember anything. But, in your music, I can hear repetition, like the Silver Case theme is used, and reused with variation, to the point where I can remember the theme right now. How do you go about creating that feeling; that some day people will be say "Oh, I remember that time..."

MT: The technique I used in [early Grasshopper game] The Silver Case is called the leitmotif technique. It's through this that I try to achieve that sense of nostalgia. The same technique is often used in operas, where a specific melody is used for a specific character. So the soundtrack selection is based on and coupled with the character in action. For example, you have two characters with separate motifs for each, if the both characters appear at once, you would blend the two melodies. Using this technique in addition to Silver Case's main motif and theme, the tunes are rearranged over and over for each important point in the game.

I think that's a much better technique. The traditional themes that we remember, like Final Fantasy battle themes, for instance - that's largely because we heard them hundreds of times. But this is actually threaded through, so you're not just hearing the same song over and over again.

Jesse Harlin, the audio columnist for Game Developer magazine, wrote an article about techniques for making distinct themes. One of the techniques he described is taking a certain style of music and putting it in a genre where you wouldn't expect. He says the themes you remember are things like, where you take an action game like Mario, and you put a waltz in it. Or the a cappella theme in Katamari Damacy.

MT: Yeah, I think the shock factor and initial impact of the mismatch link directly to memory, so it's probably easier to remember a cappella used in Katamari Damacy than the same a cappella applied to an emotional scene.

To hear a cappella in a situation that fits a cappella makes less of an impact than hearing it in Katamari Damacy - a situation that seems like a mismatch at first, that's probably why people remember.

ASCII Entertainment/Grasshopper Manufacture's The Silver Case

What other techniques do you use to try to make music distinctive?

MT: No More Heroes is structured to have smaller squad battles and boss battles. There's a specific melody that is used for the smaller squad battles throughout the game which is also used in the game trailer. The entire game, from the opening to the ending, is constituted by this one melody. [Takada hums it.] That single melody is rearranged in a variety of ways, with varying complexity.

In the small squad battles, because lots of identical characters or enemies with the same look come out at once, by playing the main theme, you make a stronger impression of the No More Heroes game itself on the players. On the other hand, because characters in boss battles stand alone and have a greater presence, I try to omit the melody and include music with less impact.

I noticed that when you were thinking about your music, you did this [gestures as though playing keyboard] -- can you actually play the keyboard without the keyboard?

MT: Oh, you mean like this? I don't intentionally play air keyboard, but I do it for sure. Yeah, I do practice like this when I'm taking the train and stuff.

In Samurai Champloo, the music and the sound determines the combo chain that you can do, and so in a case like this, how do you create the music to work with the game?

MT: Hmm... when I wrote the music for Samurai Champloo, the game's combo change system idea wasn't solidified yet. So the music was created first and then the game was shaped around and adjusted to match it. That was the production pattern, yeah. The music was created first, then it was applied to the game system, then we went back to making fine adjustments.

And do you feel that was a successful implementation?

MT: Yeah, it wasn't a flop so... (laughs). The programmers of Samurai Champloo had good sense.

How do you feel that music composition has changed with the next generation of consoles?

MT: The big change is that it's become surround sound, so you have to make all the audio for a surround environment.

And how do you find developing sound for surround instead of stereo?

MT: In Japan, surround systems themselves haven't become widespread, so... it's pretty difficult, or more like it's doubtful whether you can have the player play the game in the environment you have in mind. In terms of the game itself, I think to be able to simulate the sound of something popping out from behind expands possibilities.

But of course Grasshopper's games don't really sell in Japan; they sell in the U.S., so it must be something you're starting to think about now.

MT: That's true. I'll work on it (laughs).

Adaptive music is not used very often in Japan. Why is that? I'm referring to music which changes with the state of the game. Rather than the more typical situation, where you walk into an area, and when you're in a combat mode, the music changes.

MT: Actually that is the sort of thing I want to do... for The Silver Case, they did it. So, the sound... It's a limited sort of interaction, such as a desktop computer in the game where you can see some data is just displaying on the screen, and depending on the state of the user, the soundtrack, the music - the background music at the moment, for the data you see on the screen, would be changing.

I'm wondering why it's not used too much in the industry. Because also, to explain it a bit better, it's like a situation where it's not just 'you reach a boss and the boss music changes', it's like actual dynamic change to affect mood on the screen.

MT: If you take the case of a game where the BGM changes with respect to the program, with the Xbox 360 and the PS3 we should be able to do it, but with consoles - for example with respect to the Wii, it's harder to have the multi-track coordination with the programming.

How did you develop the very crisp and clean Grasshopper audio style? I'm talking whole sound design. Because it all really works together.

MT: I'm just doing my best to make audio that matches the game. People often say that my sound effects have personality, but I'm not sure why.

But certainly, you want to create your own style, right? So that people will know that it's yours.

MT: To the contrary, I don't think about that much. I don't know if you would call it compulsive, but when I put my hand to the keyboard, the colors of the sound composition just flow like it's a memory implanted in my spine. Instead of over-thinking it, most of my work is compulsive; when I play a tune and the melody seems right, that's what I go for.

Well, a lot of sound designers and composers now, they create very standard things. Perhaps you're not actively trying to do something different, but Grasshopper claims to be a "game development band," right? So they're trying to do something not exactly like everyone else. So how do you create this distinction, and when you think of a Grasshopper game, how are you making that sort of soundscape?

MT: I find that fascinating (laughs). I wonder why. When I'm thinking about creating sound effects, I am cautious that the key of the sound effect doesn't end up clashing with the running BGM.

Well, in Killer7, for instance, you have music, and then you have the sound design that ultimately brings you into the game, and then does something unexpected to push you out again, and make you realize, "OK, this is a video game. I'm not in this world. This is really a game." It's a very "game-like" sound. Most people are trying to make "movie-like" sound, that just envelops you, and brings you in, so you never remember what you're doing. But with the kinds of surprises in these games, a player feels like, "OK, this is a game. I'm still playing a game."

I don't know if it makes sense in Japanese, but it's an "opaque" experience, where it's just all the same experience. There are no seams. There's nothing like that. It's all smooth, and you watch it all the way through. As opposed to a "transparent" experience, where you can see the technique, and it's just like the sound is part of telling you what you're doing, lets you know it's a "game-like" game.

MT: For Killer7, I actively asked the programmer to implement the game audio, so as I played the game I made lots of adjustments. All of the sounds that I didn't want in the game were all omitted. I only kept the sounds that I thought were vital.

Basically I match the scale and adjust sound effects to the specific setting; I sprinkle in sound effects in the same way I work with music; on the other hand, when I don't want to draw the user in, when I want to push them away, I intentionally tune and apply sounds that are slightly off pitch from the optimal adjustment.

Capcom/Grasshopper Manufacture's Killer7

How do you decide when it's time to bring them in, and when it's time to make them feel uncomfortable?

MT: Well, I ask [Grasshopper boss Goichi] Suda, and... [laughs]. It's vague, but I play it myself and... [long pause] Basically you advance in games and you want the user to progress and go to the next step... Is that okay? This is hard!

Sorry. If you didn't make interesting music and sound, I wouldn't have to ask difficult questions!

MT: [laughs] I may sound arrogant right now, but I'm really happy to know someone notices and understands that much about my work. I don't understand English, but I feel like I'm able to communicate with music.

Well, music is kind of its own language after all. So it can really communicate a lot more than words can, and I think it's something that is really done well here. So in a way that's kind of back to my question about developing the Grasshopper Manufacture style; how did you create your language for games?

MT: My own style? I... I don't consider myself, or want to become, an artist; instead, I want to be a craftsman. If someone tells me they want a certain type of song, then by all means, I have the desire to write that song. So from Japanese enka to classic orchestra, I've always wanted to be diverse and able to write anything and everything.

Let's try again with that earlier question from another angle - how do you make users feel uncomfortable but still keep them involved?

MT: Well, balance... How do I make them continue? It has to be good music, or more like as long as I continue to write music that users like; for example, to maybe motivate the user to continue by having them anticipate a new BGM if they reach the next boss battle.

And then how, within that framework of keeping them, do you make uncomfortable or jarring sounds that do not make them turn the system off?

MT: You must break through. Maybe you would call it a trial. Midsize bosses... how would you put it..? If you defeat him, you can move on to a comfortable place that just lies ahead. I want to do things like that. If you have nice music here, there are also uncomfortable moments, and then here you get good music again [gestures in an arc]. So in order to get here, you choose to move forward through a thorny path. As long as there's a fluctuation in emotions it's good.

For instance, in survival horror games, like Silent Hill, the sound design might make a player feel "Oh my god, I don't want to go over there!" but still you go, because you feel compelled. It seems a little more complicated than the emotion of hoping for something good in the future. Something about it makes you feel scared or uncomfortable but you have to figure out what that is, so you want to keep going.

Even in your own games it's more complicated than what you just said. It's a little deeper. And if it were an even pattern of bad, good, bad, good, that would be very predictable, but in Grasshopper games, it's like good, then surprise, and then maybe bad, then surprise, and then...

MT: That's true (laughs). If you have to name one example that's what it's like, but according to Suda's thinking itself, his main goal is to surprise users. So if you look at our project plans, gameplay is broken up by cutscenes and so forth - that's how Killer7 was made.

We, on the creating side, are often surprised ourselves. Because it's Suda's game there's that flow, and the flow of the audio also needs to... if there's a surprise here, you adhere here, sort of like that. That's what I think.

From the developer point of view, I know there's a surprise here, so the key is how to rouse up the experience and take it to the next level, so immediately before I would take the audio down a notch and stuff, to create a wave [gestures]. That's how I create the audio.

So it's like an algorithm of high and low points? I think maybe you don't give yourself enough credit by saying it's all Suda, because I've asked Suda about this, and he said to ask you!

MT: Is that so? It's true that writing music for Grasshopper games compared to writing music for titles under other companies like, God Hand, Earth Defense Force - and that goes for Beatmania too - is like using a completely different area of the brain.

With the audio design that you do for Grasshopper, with the wave and the algorithm and all, do you map it out? Do you make a chart of it as far as the user experience? I mean the figuring out of where to put things. And if so, do you make an audio map?

MT: Not at all. Not at all, but only for Grasshopper games, audio specifications aren't included in the project plan, so I don't know how many songs or what sound effects are needed until the very end. So until the game is complete, I have no idea how many songs I need to write.

Is all your sound designed to the game, then, or is the game sometimes designed for the music you've written?

MT: I'm shown the game in the beginning, during the concept stage when it's not yet confirmed for production. In response, an image of what I want to do and how I want to proceed is mostly formed during this stage.

You're talking about the design document stage?

MT: Yeah. After that I discuss it with Suda. I explain the relative idea and feeling, write a few pieces, try imposing them onto the game, and then Suda makes the final judgment. Recently, I've been doing whatever I want. First, I apply the audio to the game. Suda listens to the audio in the game and makes a call; whether it's a no-go or an OK, I have him decide.

Not often [do I make music before the game is created]. How do I put it... sometimes it's hard to determine whether the audio works, from the music alone. There are times when you can't tell if it matches or not, so I try to apply the audio to the game while it's running before making a decision.

It sort of reminds me of the relationship between Sergio Leone and Ennio Morricone. You know what I'm talking about?

MT: Yes, I see.

So then, with the sound effects, when you know, "Okay, this is a part we want to surprise people," and you're doing this to get to this point of that rise and fall of emotion for the player, once you have everything ready, is that something that you can chart? Because if you're working with a prototype, you have to know where this point is and how to get to that point right.

MT: About that, it's not just the sound effects, there's enemy placement, where the enemies are and stuff, these things also need to be consulted with and have the input of the level designer. So depending on the ability of the planner, a common pattern is where audio is also automatically placed in a similar fashion. So I don't [make a sound map]. I trying playing the sound and then determine what's needed where.

What is your favorite of your own soundtracks?

MT: It has to be Killer7.

And, of all game soundtracks in general, not yours?

MT: Oh, from other composers?

Maybe not the best, but what you like; your choice of best five, or good five.

MT: I think I haven't even listened to five game sound tracks!

Well you said you liked games before you came... They don't have to be current.

MT: Let me see... I like the Fire Emblem song and stuff. What else? And...

Four more.

MT: (Laughs) Mappy! Back in high school I played it on the piano in the music room, and it made me popular. Also Xevious. I like music from the Namco shooting games too. I love the BGM of Galaga Plus and Druaga.

Tim Rogers: Older games had more of a pop music feel to them. Games today are somewhat overly complicated and thematic.

MT: Yeah, just listening to the music, the old games were more interesting.

Do you ever make your own music outside of games?

MT: Yeah. I've been writing music since I was in elementary school. When I listen to the tunes I wrote back then, I think "Wow, I was innocent." They're not... twisted, or convoluted and I'm not quite sure where to use them (laughs). Yeah, if I had time I would like to write more music. Recently, I've been providing the songs I write for personal reasons to Beatmania, so even if I write a song that I like, it eventually becomes game music.

The soundtrack for Earth Defense Force is very different from a Grasshopper soundtrack, and I wonder sometimes if you save your best work for Grasshopper.

MT: Umm... That's true. To be honest I always have a few prewritten tracks on stock that are waiting for the right moment to make a debut. I try to use them on Grasshopper titles, but in the case where they are rejected, the songs go back into the reserved stock.

Status-wise, a piece that has been rejected by Grasshopper once can never be used for Grasshopper again. I feel sorry for the song if it's never used, so I use it for other titles. Every song that you write yourself is like your own child, so ideally, you want as many people listen to it as possible.

D3/Sandlot's Earth Defense Force 2017

And were you in-house at [Earth Defense Force 2017 developer] Sandlot before you came to Grasshopper? I know you did lots of music for them.

MT: Ah, so when I was working for Grasshopper, Sandlot was previously part of the company we were in before, so lots of my coworkers went there.

I was in charge of the sound for several of their titles, but no, not in-house. I was part of Grasshopper, but just helping Sandlot with their music. I guess it was sort of like freelance.

So I assume you're saying that Sandlot was another company that came out of Human? [Human Entertainment was a large Japanese game developer that went out of business in 1999, splintering into many smaller companies.]

MT: That's right.

So there's Sandlot, Grasshopper, and who else?

MT: Spike, too. Of course my coworkers went all over the industry, but let me think about who actually started a company. Right, there was [Hifumi] Kouno, who made [Steel Battalion co-developer] Nude Maker. I did some of their sound, too.

You must be busy! And you're still doing music for Sandlot and Nude Maker?

MT: Yeah, when I have time, I mean when they bring something up, we have those sorts of discussions...

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like