Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

"Rock Balls": The Making of WarCraft II

Fresh off of WarCraft, Blizzard Entertainment's developers sought to prove their success wasn't a fluke, and designed one of the most influential and critically acclaimed strategy titles of all time.

Author's note: The following chapter comes from Stay Awhile and Listen: Book I, now available along with Stay Awhile and Listen: Book II as part of StoryBundle's "Boss Battle" Game Bundle. The promotion features 10 DRM-free digital books for $15 and runs through the end of April; a portion of all proceeds will go toward Doctors Without Borders to aid medical professionals as they battle the novel coronavirus.

It wasn't the numbers we sold that made us realize we had done something special with WarCraft. I think it was the play experience. WarCraft was really fun to play. It had a different look and feel from the other games out there. It was more like a cartoon. I hadn't seen anything like it before. It was amazing and just so damn fun.

-Frank Pearce, co-founder, Blizzard Entertainment

If you look at the title credits for our early games, they say "Design by Blizzard Entertainment," and that was a conscious decision. A lot of people were deeply involved in the design process, and it's hard to single out all of those folks.

-Pat Wyatt, vice president of R&D, Blizzard Entertainment

We definitely make games that we want to play. By making games that we want to play first, we're able to make better games.

-Samwise Didier, artist, Blizzard Entertainment

BLIZZARD ENTERTAINMENT'S PUSH TO GET WarCraft: Orcs & Humans on shelves in time for Christmas 1994 left Allen Adham's team weary yet satisfied. Like the proverbial snowball rolling downhill, sales started off slow then picked up through January as critics took notice. PC Gamer magazine gave the game an Editor's Choice award and named it runner-up for Strategy Game of the Year. Computer Gaming World magazine and the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences chimed in, granting Blizzard's maiden PC title Best Strategy Finalist status.

BLIZZARD ENTERTAINMENT'S PUSH TO GET WarCraft: Orcs & Humans on shelves in time for Christmas 1994 left Allen Adham's team weary yet satisfied. Like the proverbial snowball rolling downhill, sales started off slow then picked up through January as critics took notice. PC Gamer magazine gave the game an Editor's Choice award and named it runner-up for Strategy Game of the Year. Computer Gaming World magazine and the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences chimed in, granting Blizzard's maiden PC title Best Strategy Finalist status.

Bob and Jan Davidson gave Blizzard's boys little time to recoup. The Davidsons wanted a sequel, and they wanted it by Christmas—only eleven months away. Allen and his team saw the wisdom in following up WarCraft sooner rather than later, but they also saw the value in tempering haste with careful consideration. Every developer had suggestions to make WarCraft II bigger and better.

One school of thought was more modern era stuff where humans had fighter jets and modern technology, and Orcs rode around on dinosaurs and cast magic spells. A lot of people in the office thought, That's a cool idea. Let's not just do the same thing over again. Let's go somewhere different.

It was probably best [that WarCraft II retained its fantasy theme] because we didn't know that Command & Conquer was in development [at Westwood Studios], which meant our game would have been too close to C&C's modern warfare-themed units.

-Pat Wyatt

That was a huge fight between me and Allen. Allen wanted to take WarCraft II into space, and I was like, "No, that will destroy the title. That will kill it." Allen and I went back and forth, back and forth on this. At one point, a Calvin & Hobbes comic strip [printed 1-1-1995] had come out showing Calvin playing with a dinosaur toy, and he made the dinosaur [pilot] jet fighters. The last frame of the comic showed Calvin playing and saying something like, "This is so cool!" And Hobbes was saying, "This is so stupid."

Someone pasted that comic on the doorway with "Stu" written under Hobbes and "Allen" written under Calvin. Allen saw the comic. I saw his shoulders kind of slump, and he said, "Okay. I get it."

-Stu Rose, artist, Blizzard Entertainment

Blizzard's team had no intention of phoning in a quickie sequel. They wanted to add more units, more strategies, more maps, more players able to mix it up in multiplayer—more everything.

The WarCraft design document I wrote is probably the furthest we got with design documents. I don't remember if there even was a design document for WarCraft II. We knew we needed barracks, we needed town halls, and we already knew what their functions were.

-Stu Rose

Early photo of the Silicon & Synapse/Blizzard Entertainment team. Top: Patrick Wyatt. Below Pat, in the center: Joeyray Hall. Far right: Michael Morhaime, and Stu Rose to his left. Middle row and far left: Frank Pearce. Front, from left: Samwise Didier and Allen Adham.

To add new layers of strategy to the familiar "gather resources, raise an army, and destroy opponents" gameplay, the developers added island maps to the mix of forest and grassland battlegrounds. Traveling between islands required players to build shipyards and send oil tankers out to install refineries overtop oil patches. Combined with gold and lumber, a steady supply of tankers sucking up oil from the seafloor enabled players to construct warships to patrol the high seas and transports to ferry troops between islands.

Oil originally worked much differently. The way it worked was you'd send out a ship into water, and you'd press a button for that ship that would start this radar-like ping. And you'd see, on the minimap, "This area's dark so it has lots of oil" or "This area's light so it has no oil."

I argued vociferously against that idea. We implemented it [to experiment], but I hated it because it involved a lot of micromanagement, and that was antithetical to the spirit of WarCraft II, which used a much faster play style to that of WarCraft.

-Pat Wyatt

Blizzard refreshed the Orc and Human rosters to give veteran players new tactics to try. Footmen, Grunts, and Archers returned, but the Orc Spearman was replaced by the Troll Axethrower. Both sides received updated long-distance, heavy-damage units in the Human Ballista and Catapult, Gryphons and Dragons sprayed magic and fire across the skies, and Dwarven Demolition Squads and Goblin Sappers exploded when they collided with buildings, units, and even solid rock.

A version of the game leaked, which we called WarCraft II Alpha. A German magazine we'd given a preview copy to let it leak out. We were super pissed off about it, but it gave players an opportunity to see an early version of the game.

The resources were gold, lumber, rock, and oil. At some point after that, we decided that there were too many resources; it made the game too complicated. So we cut rock as a resource, but you could go around with Goblin Sappers and Dwarven Demolition teams and blow holes through mountains to get to somebody's base that might otherwise only be accessible by water.

I'm glad we were able to use that because I didn't want to see harvesting rocks go to waste.

-Pat Wyatt

As in the first game, WarCraft II's factions largely mirrored one another. The Human Mage had 60 health points and cost 1200 gold to build, the same stats as the Death Knight on the Orc side. Human Knights galloped around on horseback but did the same damage as the two-headed Ogre that lumbered about on foot. Where the Orcs and Humans differed was in tactics and abilities that opened up after players had constructed advanced buildings. After building certain prerequisite structures, players gained the option to convert Knights into Paladins that healed friendly units on command. Ogres transcended into fearsome Ogre Mages able to cast Bloodlust, a spell that enhanced a unit's speed and strength.

It's much easier to differentiate [factions] in the late game because you have less risk of one side being unbalanced compared to the other than you do in the early game, where differences are critical. Really what you want is for both sides to build up and then have tactical options that split in different directions [in the late-game stage].

Now, interestingly, we still made a mistake. Paladins are really underpowered compared to the ogre mages. From a micromanagement standpoint, Ogre Mages are much more powerful because you can cast bloodlust on all your guys then go attack, and your troops will go about their business. With the Paladin's healing, you have to wait until the unit takes damage then heal [manually].

The Paladin required a lot more micromanagement, and that was something the design team didn't perceive as being a balance issue at that point, but it ended up being a big deal. Orcs were a much better race to choose in WarCraft II.

-Pat Wyatt

Outside of new units and faster gameplay, WarCraft II underwent numerous under-the-hood changes. In August 1995, Westwood Studios released Command & Conquer, the spiritual successor to the studio's Dune II RTS that had influenced WarCraft. Blizzard's developers played Command & Conquer extensively and applauded some of the adjustments Westwood had made to the RTS genre's gameplay. Notably, Command & Conquer eliminated the need to click command buttons like Attack and Move by implementing an intelligent interface driven by the left mouse button. After selecting units, players simply left-clicked on the ground to move, left-clicked on enemy units to attack, and left-clicked on buildings to select them.

Blizzard's programmers appreciated Command & Conquer's streamlined controls but encountered a common problem: because every action was mapped to the left mouse button, players sometimes performed actions they did not mean to, such as sending a pack of troops charging forward when they had intended to move their cursor up a smidge more to click on a building and peruse its upgrade options. Jesse McReynolds came up with a way to reduce such user errors in WarCraft II. Pulling up the game code, he divided functions between both mouse buttons. Left-clicking selected units and buildings, while right-clicking carried out context-sensitive actions like moving and attacking.

Another improvement was the fog of war, a black shroud that covered all terrain at the start of each game except for the player's starting location. As in WarCraft and Dune II, the darkness peeled back as the player sent units roving across the map, revealing terrain, gold mines, forests, and enemy bases. WarCraft II one-upped the fog mechanic by adding a new layer of strategic possibilities: Terrain and enemy structures remained visible after the player's units moved away or were killed, but in the state the player had last seen them, as if frozen in time.

What ended up being really challenging was [drawing] the knowledge of what the player had seen in an area. Mike Morhaime might have written code for this: You go to explore an area, and you happen to see a building, maybe a barracks. Then you go away.

Well, is that building still there, or not? What if that building gets destroyed or more buildings appear around it [before the player returns to that area]? I can't just show all the buildings that are there in the fog; I need exact information about what the player saw. You don't want to give away information like a building that signifies the [opponent's] production of Ogre Mages.

We did that by making shadow buildings. Each player sees what he saw, and shadow buildings represent the buildings that were there when he scouted the area, but might not be there now.

-Pat Wyatt

Crafty WarCraft II players used the fog of war to their advantage.

The idea of roads [in WarCraft] was taken directly from Dune II. In that game, you could only build buildings next to roads, and roads had to connect to other roads. So the designers were able to control where you could build buildings, or not build them, by laying out roads on the map.

We argued about that quite a lot in the early design process [for WarCraft]. Allen was one of the chief proponents of roads. He pointed out, "What if someone builds a barracks right next to your base?"

-Pat Wyatt

With roads out of the way, WarCraft II players could initiate construction on any patch of clear land. Devious generals made a habit of sneaking a worker unit just outside an enemy's base and walling them in with watchtowers, constructing farms in a line that blocked access to gold mines and forests, and building a barracks that pumped fighters right into the base.

Another improvement offered in WarCraft II was as technical as it was cosmetic.

Super VGA graphics were not very popular for games yet. Windows 95 was coming out, and Allen said, "We need to do a hi-resolution Windows game."

Having worked on one of those—that was MPC Battle Chess—I said, "To do [high-res graphics] for a real-time strategy game is not possible."

-Pat Wyatt

Pat argued to Allen that rendering high-resolution graphics on the screen would prove too taxing on contemporary computers. Video games had to refresh the screen every time players performed any action like scrolling and moving a unit around. Refreshing super-detailed images every few seconds would slow WarCraft II to a crawl. As was standard at Blizzard, the push-pull argument turned into a raging debate that swept up the whole office.

Allen would say, "We have to do this," and I'd say, "No." Lots of other people were saying "No." We had a meeting where he railed on a whole group of us. He said, "You say 'no' to this, and this, and this. I want to do something, and I can't do anything around here."

So I gave up and said, "Okay, we'll do Super VGA," and it was really hard, but we were able to pull it off for WarCraft II.

Allen was right. Sometimes we just had to try to do impossible things and succeed or fail. Fortunately we succeeded more often than we failed, but those kinds of arguments really wore him out.

-Pat Wyatt

WarCraft II's resolution doubled in size, enabling the artists to create maps, buildings, units, and special effects that were sharper, crisper, and more detailed than WarCraft's already-dated graphics. Although the resolution changed, WarCraft's cartoony graphics and humor remained intact.

We doubled the resolution of the game so we could insert all these details we didn't see before, and I did a test with some realistic Orcs running around. They were just rendered sprites, but they were rendered in 3D with armor and skin tone and everything.

I really liked it, and a lot of people really liked it. It was a totally different look. But then some of the other designers came in and said, "No, it's got to look more cartoony. It's got to look more goofy."

As a petulant kind of "Fuck you," I turned the shaders all the way up on the characters so they were 100 percent saturated, like obscene neon and glowing green, just to show them how ridiculous it would look. And they said, "Yeah, that's it. That's what we want."

Shot myself in the foot on that one. We dialed it back maybe 10, but that's what the game ended up looking like.

-Duane Stinnett, artist, Blizzard Entertainment

Honestly, I think it [the WarCraft series' color palette] was more an effect of doing so many Super Nintendo games. If you look at Blackthorne, [vibrant] colors was just the style we used at Blizzard, and we carried it over into WarCraft. Blackthorne, Justice League, Rock 'n Roll Racing--that was just the style of the art we made.

-Stu Rose

Without a story beyond "Orcs and Humans fighting each other," Bill Roper had made up WarCraft's dramatic plot and history on-the-fly in sound booth recording sessions. For WarCraft II, Blizzard handed over world-building duties to an enthusiastic new artist.

I was singing in a few bands and just having a blast at that. [...] We were playing a gig at a club one night, and I guess I had drawn a little dragon on a cocktail napkin, just screwing around. And this guy walked by who knew a friend of a friend of a friend and went, "Hey, that's pretty good! [...] I know this one place that's hiring artists." And he handed me a card that said "Chaos Studios."

[...] I walk in the door and there's radio-controlled cars and superhero posters and Iron Maiden posters all over the walls. I didn't even know what they did. All I knew is that whatever this is, I want a piece of this.

-Chris Metzen, artist, Blizzard Entertainment

Metzen had started out animating Batman on the Super Nintendo version of Justice League Task Force. Eager for more work, he pitched in on the text and detailed illustrations that made up WarCraft's instruction booklet. When the team started in on design idea for WarCraft II, Metzen let his imagination run wild.

By the time we began WarCraft II, I stayed late and wrote up a few paragraphs of what might have happened between the games that would set up a sequel, or begin to set up the scope or anticipation of the sequel. I didn't plan to show it to anybody, and I guess one of the other designers showed it to the boss one night, unbeknownst to me.

A couple of days of later, we're at a meeting, and the boss says, "Oh, and, by the way, Chris is our new designer on WarCraft II."

I'm like, "Holy crap! Really?! Why?" But he knew. He knew that while I loved drawing [...] ultimately he knew I just wanted to make stuff up.

-Chris Metzen

Metzen submerged himself in the fiction that defined Azeroth and its surrounding lands. Picking up where Bill Roper's off-the-cuff construction of the lore had left off, he decided that the Orcs had won the first war, leaving Azeroth in a state of desolation and panic. All surviving humans retreated to the kingdom of Lordaeron. Eyeing another conquest, the Orcs set off in pursuit.

To expand the scope of the game, Metzen and the other designers brought other races into the Orcs-versus-Humans conflict. Elves and Dwarves sided with humanity to form the Alliance, and the Orcs rolled trolls, ogres, and goblins into their ranks. Metzen's yarn of conquest and bloodshed unfolded over the game's two campaigns. Players who took command of the battered and bruised Alliance explored, built, and fought their way to a final showdown at the Dark Portal from which the Orcs had invaded. Those who threw in with the Orcs set off on a string of plundering and pillaging that culminated in an all-out assault on Lordaeron.

Chris Metzen used to be this kid who had a lot of brilliant ideas about story. He wrote the story for WarCraft II and beyond. He didn't do a good job of expressing how cool things were going to be in meetings, but when he delivered the goods, they were always epic.

The terms he used to describe what our games should be were, "[The game] needs to be epic. Bold, epic, and rock balls." We all just sort of knew what that meant even though it sounds really wacky. It had to be bold and epic, and it had to "rock balls." So that's what we did. We made games that rocked balls.

-Pat Wyatt

Alongside Sammy Didier, Metzen also helped evolve the cartoony visuals used in WarCraft.

I think the cartoony look definitely works. Compared to other games out there, which have a main character who is a normal guy, [WarCraft: Orcs and Humans had] this giant massive green Orc riding a wolf, with an axe that is too huge to carry in one hand, yet he's got two of them, one in each hand.

Everything is just over the top.

-Sammy Didier, artist, Blizzard Entertainment

Sammy Didier was very much the driving force behind the look of WarCraft [series], and he always has been. Between him and Metzen, they had this "it's goofy and cartoony, but it's badass at the same time" style.

-Duane Stinnett

Saving or decimating Azeroth for a second time offered plenty of action and drama, but Blizzard's developers knew multiplayer was the reason players continued to play WarCraft long after they had finished the game's story. Just like the artwork, gameplay, and storyline, multiplayer offerings in WarCraft II needed to be exponentially better. WarCraft had permitted only two players to engage in epic, rock-balls clashes. WarCraft II quadrupled that limit, offering dozens of maps set in forests, islands, and winter wonderlands—complete with twinkling Christmas lights that fit in perfectly with WarCraft's jocular personality—for up to eight players.

Even more important to WarCraft II's success was its multiplayer play. Although it lacked the free Battle.net connectivity of later Blizzard products, it did feature eight-player local network play and supported two-player modem gaming. It was also another early beneficiary of Kali, a gaming community tool that allowed primitive TCP/IP gaming connections across the nascent Internet.

-Jason Bates, PC Retroview, IGN.com

Blizzard Entertainment released WarCraft II: Tides of Darkness in early December 1995, right on schedule. One year earlier, the original WarCraft had been just another box amid dozens of other games at retail. From the moment the sequel dropped, hype for the game swelled from a snowball rolling downhill to a full-on avalanche.

Cool is one word for it, but blockbuster hit is another way to describe WarCraft II. It became Blizzard's first game to hit the million-unit-seller mark. [...] Up until that point only games like Myst and The 7th Guest could claim such a distinction.

-Geoff Keighley, "Eye of the Storm," GameSpot.com

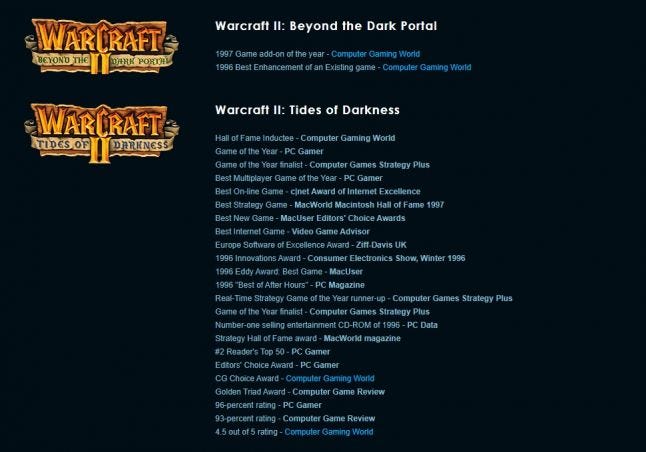

Critics and gamers responded to WarCraft II right away. PC Gamer piled on the praise, bestowing an Editor's Choice Award and crowning it Best Strategy Game of the Year and Best Game of the Year overall for 1995. Years later, GameSpot.com, Computer Gaming World, and other venerable media outlets inducted the game into their respective Hall of Fames.

Once you had learned the nuances and intricacies of multiplayer WarCraft II, you'd find yourself hopelessly addicted to fine-tuning your build orders in an effort to find the most efficient play style possible.

Team games could involve certain team members getting extremely specialized—for instance, one team member would try to get dragons or demolition crews as quickly as possible while the other team members would protect him or her. Water maps with battleships and ship transports added yet another wrinkle to the game strategy.

-Bob Colayco, "The Greatest Games of All Time," GameSpot.com

Critics also expressed satisfaction with the game's accessibility and personality.

In WarCraft: Orcs and Humans, I always took umbrage at having to tell a unit what to do when, in many cases, it should be obvious: if you tell a peon to go to a gold mine, you want him to harvest gold.

WarCraft 2 lets you right-click to quickly dispatch your units. Click on clear ground and you move there. Click on an enemy unit and you will attack him. If you've been playing a lot of Command & Conquer lately, you'll welcome this feature.

-Tim Keating, Computer Games Magazine

Although no reviewer ever put it in Metzen's words, Blizzard's developers knew WarCraft II rocked balls. Other developers thought so, too. Caught up in the excitement over the growing popularity of the RTS genre, competitors littered store shelves with imitators that tried but failed to pry loose the grip that Blizzard and Westwood had on think-on-your-feet strategy gaming.

Just as importantly as ushering in waves of real-time warfare games, WarCraft II proved that Blizzard was no one-hit wonder. Never again would a Blizzard Entertainment-branded game get lost in the shuffle of other boxes. For gamers and critics, the next great PC game developer had arrived.

Author's note: This chapter chapter comes from Stay Awhile and Listen: Book I, now available along with Stay Awhile and Listen: Book II as part of StoryBundle's "Boss Battle" Game Bundle. The promotion features 10 DRM-free digital books for $15 and runs through the end of April; a portion of all proceeds will go toward Doctors Without Borders to aid medical professionals as they battle the novel coronavirus.

Bibliography

The Stay Awhile and Listen series is written based on extensive research and firsthand interviews. This chapter came from interviews with Patrick "Pat" Wyatt, Stuart "Stu" Rose, and Duane Stinnett. Additional sources of information include:

It wasn't the numbers were sold: "Frank: Warcraft!" Blizzard Entertainment. February 2001. http://web.archive.org/web/20020222122116/http://www.blizzard.com/blizz-anniversary/frank.shtml.

We definitely make games that we want to play: "Samwise: That Blizzard Magic." Blizzard Entertainment. February 2001. http://web.archive.org/web/20020207175825/http://www.blizzard.com/blizz-anniversary/samwise.shtml.

I was singing in a few bands: Brodnitz, Dan. "An Interview with Blizzard's Chris Metzen, Part 1." About Creativity. 21 April 2008. http://about-creativity.com/2008/04/an-interview-with-chris-metzen-part-1.php.

By the time we began WarCraft II: Ibid.

I think the cartoony look definitely works: "Samwise: That Blizzard Magic." Blizzard Entertainment. February 2001. http://web.archive.org/web/20020207175825/http://www.blizzard.com/blizz-anniversary/samwise.shtml.

Even more important to WarCraft II's success: Bates, Jason. "PC Retroview: WarCraft II." IGN. 31 January 2002. http://www.ign.com/articles/2002/01/31/pc-retroview-warcraft-ii.

Cool is one word for it: Keighley, Geoff. "Eye of the Storm: Behind Closed Doors at Blizzard." GameSpot. 4 January 2011. http://www.gamespot.com/gamespot/features/pc/blizzard/p2_07.html.

Once you had learned the nuances and intricacies: Colayco, Bob. "GameSpot Presents: The Greatest Games of All Time - WarCraft II: Tides of Darkness." 3 April 2013. http://uk.gamespot.com/features/the-greatest-games-of-all-time-warcraft-ii-tides-of-darkness-6144203/.

In WarCraft: Orcs and Humans, I always took umbrage: Keating, Tim. "Warcraft 2: Tides of Darkness." Strategy Plus, Inc. 1996. http://web.archive.org/web/20030130180010/www.cdmag.com/articles/004/046/warcraft_2_review.html.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)