Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

“Gamerliness” – How Games Can Evolve By Looking Inward

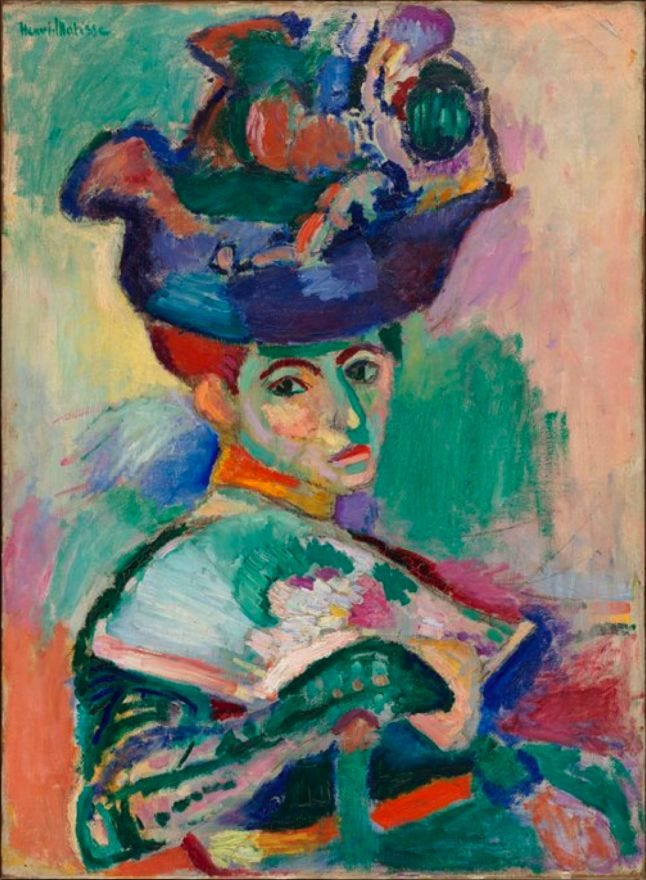

Henri Matisse's art was "painterly." It used visible brushstrokes and strange colors to create a sense of unreality that was unique to art. Film and literature have tapped into this feeling, too. But what if games did?

Hey everyone, I’m back! Sorry about the hiatus, but I got so stressed out for a while there that I resorted to covering myself in stuffed animals and refusing to get out of bed in order to stay sane.

(Sort of like this.)

Anyway, onto today’s topic. If you’ve ever studied art, you may have heard of the term “painterliness” used to describe works of art that derive meaning from drawing attention to the fact that they are just paint on a canvas or clay molded by human hands. “Painterly” art doesn’t try to look realistic – instead, it uses its unique aspects as a constructed object to its advantage.

(Henri Matisse’s Woman With A Hat, 1905. Its visible brushstrokes and strange color choices give it a unique style that only a painting could produce.)

Aspects of painterliness have been used by other media, as well. Charlie Kaufman’s Adaptation (which I would love to talk about someday) does this for film, while Cormac McCarthy’s The Road uses it in the form of literature. The entire backbone of both of these pieces is based on drawing attention to concepts and styles unique to film or written literature.

(Seriously, watch Adaptation sometime. It’s hilarious and completely deranged, plus it has both Meryl Streep and Nicholas Cage in it. What more could you want?)

So what does this have to do with the evolution of games? Well, I believe that one way games can evolve as an art medium is to really dig deep into what makes games what they are. What makes them unique? What can games look like, feel like, and do that no other medium can? And then, with that knowledge, we can make games that explore those traits in a deep and intellectually challenging way.

Sure, games have drawn attention to themselves like that before, but so far it’s mostly been for parody or satirical purposes. And if it’s done seriously, then the “gamerliness” (for lack of a less ridiculous-sounding word) is just a small part of a larger unrelated whole.

One of my favorite Flash games, Achievement Unlocked, is a fantastic example of the first type – using “gamerliness” for the sake of parody. It’s more fun to just let you play the game than for me to try to explain it, so here’s the link. It’s free, and messing around in it will only take you a few minutes.

The great thing about Achievement Unlocked is that, even when unlocking the achievements gets more difficult than doing minute things like walking to the left or staying alive for 10 seconds, they’re still lots of fun to find. That childlike glee at getting so many rewards is satisfying every time, even though we know that the game is making fun of achievement systems in general for relying on such instant gratification.

The “gamerliness” here lies in parodying useless achievements by making a whole self-aware game about them, but it goes one step further. We don’t just laugh at the joke and move on – we begin to appreciate the game for its creativity and genuine charm that it displays when the goals get more difficult. Achievement Unlocked knows it’s a typical video game and makes a huge show of it, but then moves to rewarding pure exploration completely at the player’s own pace. This type of interactivity is more or less unique to games, but the message here is delivered in a more subtle and unconscious way than before.

The Stanley Parable did something similar with narration and choice in video games, using many of the same techniques as Achievement Unlocked. It starts as a parody, but goes in a number of unexpected directions once the player has progressed a bit and gotten a feel for the game. Still, I think we can go further.

What about Spec Ops: The Line? Extra Credits explains in this video that the game uses its outdated FPS combat to force a sense of unreality on the player (in a “this is a game, not real combat” kind of way). It’s dramatic and very similar to how Matisse’s paintings and Kaufman’s Adaptation forcibly shine a spotlight on their differences from reality, but this is only one part of a larger tone that the developers were trying to create. It isn’t the entire reason for the game’s existence, even though it contributes to the dreamlike ambience.

I hope that, as games continue to grow, we get to see a truly “gamerly” game that explores what is unique to this medium on a much deeper level. I would love to see a video game adaptation of The Road with exaggerated and deranged game mechanics swapped for literary techniques – but even then, an adaptation will always contain the heart of the original. The Road: The Game would still be about literature to some degree. I wonder what ideas developers could come up with on their own? Who knows – we may see gaming’s first Matisse very soon.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)