Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this sponsored technical article, part of <a href="http://www.gamasutra.com/visualcomputing">Intel's Visual Computing section</a>, Jerome Muffat-Meridol takes a look at Nulstein, his creation for in-game code task scheduling on multi-core processors.

[In this sponsored technical article, part of Intel's Visual Computing section, Jerome Muffat-Meridol takes a look at Nulstein, his creation for low footprint in-game code task scheduling on multi-core processors.]

I attended my first demo party in 2008: Evoke in Germany. I was giving a talk about multi-core optimization in games and how to use Intel Threading Building Blocks (Intel TBB) to efficiently spread work over threads, when this question came up: Can I use this in 64K?

The rules for 64K demos are simple, "65536 bytes maximum, one self contained executable," and the results are often unbelievable. Intel TBB happens to be a really elegant and slim library but, at 200KB, it just won't do. But, I hate to say no.

Inevitably, I couldn't help but contemplate the idea of a sort of working scale model of Intel Threading Building Blocks. It would be a minimal task scheduler, something that would be easy to study, tear apart, and play with. I was on a mission!

Nulstein is the demo I created to address this need. It shows a simple but effective method for implementing task scheduling that can be adapted to most game platforms. Click this link to download the code to Nulstein.

If you are not familiar with task schedulers and why they are useful in games, the key lies in the difference between a thread and a task. A thread is a virtually infinite stream of operations which blocks when it needs to synchronize with another thread. A task, on the other hand, is a short stream of operations that executes a fraction of the work independently of other tasks and doesn't block.

These properties make it possible to execute as many tasks simultaneously as the processor can run physical threads, and the work of the task scheduler mainly comes down to finding a new task to start when one finishes. This becomes truly powerful when you add that a task can itself spawn new tasks, as part of its execution or as a continuation.

If the idea of splitting work in a collection of smaller tasks is straightforward, dealing with situations where a thread would normally block can be trickier. Most of the time a task can simply consume other tasks until the expected condition arises, and otherwise it is usually a simple matter of splitting the work in two tasks around the waiting point and letting the synchronization happen implicitly. But we'll come back to this later on.

Breaking work down into tasks and using a scheduler with task stealing is a convenient, powerful, and efficient way to make use of multi-core processors.

From a programming standpoint, on a system with n logical cores, Nulstein creates n-1 worker threads to assist the game's main thread with running the tasks. Each worker manages its own "pile of work," a list of tasks that are ready to run. Every time one task finishes the worker picks the next one from the top of its pile; similarly, when a task is created it is dropped directly on to the top of the pile.

This is much more efficient than having one global job queue, as each thread can work independently without any contention. But there is a catch: some piles might become empty much faster than others. In these cases, the scheduler steals the bottom half of the pile of a busy thread and gives it to a starving thread. This turns out to limit contention considerably because only two threads are impacted by the mutual exclusion necessary to carry out this operation.

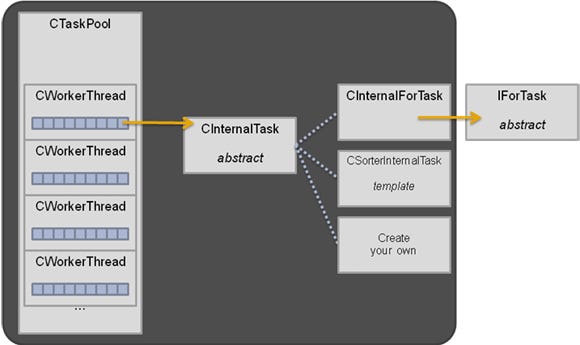

Figure 1

The task engine code is in TaskScheduler.h/.inl/.cpp (header, inlines, and code). CTaskPool is primarily a collection of CWorkerThread, where the bulk of the logic resides. CInternalTask is the abstract superclass for all tasks; you will use subclasses of this class in the implementation of ParallelFor and CSorter.

ParallelFor is the simplest form of parallel code: a loop where iterations can execute independently of each other. Given a range and a method to process a section, work is spread over available threads and ParallelFor returns once it has covered the full range.

CSorter implements a simple parallel merge sort, spawning new tasks for blocks bigger than a given threshold. Although the goal is to reduce code size, this is done as a C++ template to avoid the overhead of calling a function every time two items need to be compared.

There is a very convenient effect here: code using these functions can still be understood as serial code. Code around a ParallelFor executes before and after it, just as it reads.

For uses beyond simple looping and sorting, you will need to spawn your own tasks. This is quite simple too:

{

CTaskCompletion Flag;

CMyTask* pTask;

pTask = new CMyTask(&Flag,...);

pThread->PushTask(pTask);

...

pThread->WorkUntilDone(&Flag);

}

Your specific task is implemented by CMyTask and you use Flag to track when it is done. (Note that pThread must be the current thread.) Once PushTask has been called, the task is eligible to be executed by the scheduler, or may be stolen by another thread. The current thread can continue to do other things, including pushing more tasks, until it calls WorkUntilDone. This last call will run tasks from the thread's pile, or attempt to steal from other threads, until the completion flag is set. Again, it looks as if your task had been executed serially as part of the call (and it might have, indeed).

{

CMyTask* pTask;

pTask = new CMyTask(pThread->m_pCurrentCompletion,...);

pThread->PushTask(pTask);

}

In this alternative form, the task is created as a continuation, and you don't wait for it to complete as whatever waits for you will now also wait for this new task. When possible, this is a better approach as this is less synchronization work.

These basic blocks are enough to implement all sorts of parallel algorithms used in games, in a fashion that reads serially. You still have to worry about access to shared data, but you can continue to write code that works in a series of steps which remain easy to read.

Looking at what is happening inside, you see CTaskPool is the central object; it creates and holds the worker threads. Initially, these are blocked waiting on a semaphore, the scheduler is idle and consumes no CPU. As soon as the first task is submitted, it is split between all threads (if possible) and the semaphore is raised by worker_count in one step, waking all threads as close to immediately as possible.

The pool keeps track of the completion flag for this root task and workers keep running until it becomes set. Once done, all threads go idle again and a separate semaphore is used to make sure all threads are back to idle before accepting any new task. Conceptually, all workers are always in the same state: either all idle or all running.

The role of CWorkerThread is to handle tasks, which can be broken down into processing, queuing, and stealing them.

Processing - The threadproc handles the semaphores mentioned earlier and repeatedly calls DoWork(NULL) when active. This method pops tasks from the pile until there are no more, and then it tries to steal from other workers and returns if it can't find anything to steal. DoWork also can be called by WorkUntilDone if a task needs to wait for another to finish before it can continue; in this case the expected completion flag is passed as a parameter and DoWork returns as soon as it finds it set.

Queuing - Because of stealing, there is a risk of contention. Since operations on the queue require a lock, use a spinning mutex, because you need to protect only a few instructions. PushTask increments the task's completion flag and puts the task at the top of the queue. In the special case when the queue is full, run the task immediately as this produces the correct result.

It's also worth noting that if the queue is full, then other workers must be busy too or they'd be stealing from you. Tasks also get executed immediately in the special case of a single core system because there is no point in queuing work when there is nothing to steal it; the whole scheduler is bypassed and the overhead of the library disappears.

Stealing - StealTasks handles the stealing. It loops on all other workers checking if one wants to GiveUpSomeWork. If a worker has only one task queued, it will attempt to split it in two and transfer a "half-task" to the idle thread. If it didn't split or if there is more than one, it will return half the tasks (rounding up). The fact that workers are spinning on StealTasks when their queue is empty enables them to return to work as soon as a task becomes available. This is important in the context of a game where latency tends to be more important than throughput.

There isn't much more to the scheduler than that. The rest is implementation details best left to discover in the source code. But before you do that, you should know how the Nulstein demo uses the scheduler to take maximum advantage of implicit synchronization and to achieve most of the frame in parallel.

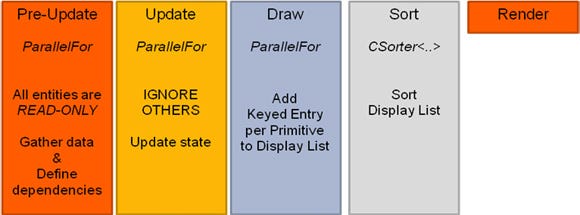

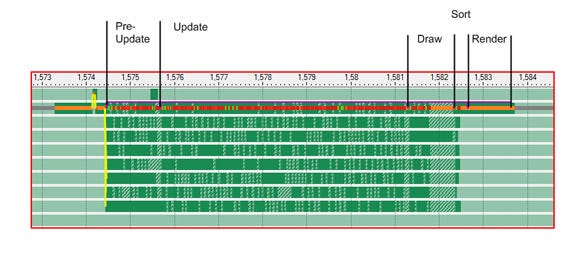

Figure 2

There are traditionally two main phases in a frame: the update that advances time and the draw that makes an image. In Nulstein, these phases have been subdivided further to achieve parallelism.

The update is split into two phases. The first is a pre-update phase where every entity can read from every other but cannot modify its public state. This allows every entity to make decisions based on the state at "previous frame." They will then apply changes during the second phase, which is the actual Update. The rule for this second phase is that an entity can write to its state but must not access any other entity.

This enables both of these phases to run as simple ParallelFor's and is trivial to implement unless there is a hard dependency between entities and you can't use the previous frame's state. A classic example would be a camera attached to a car: you don't want the viewport to move inside the car and need to know its exact position and orientation before you can update the camera.

In these cases an entity can declare itself dependent on another entity (or several entities) and be updated only once it has been updated. And because you know they have finished updating, it's okay for the dependent object to read the updated states. In the demo, this is how the small cubes manage to stay tightly attached to the corners of bigger cubes.

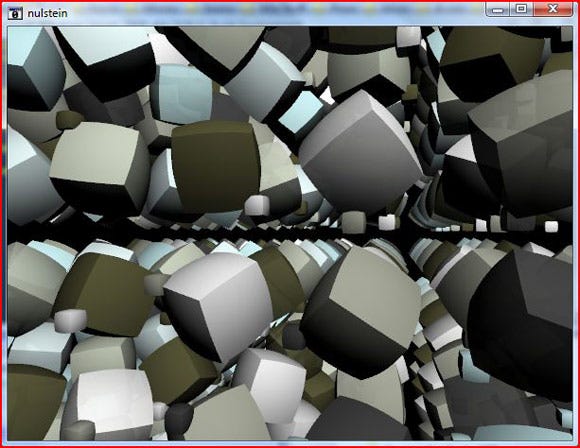

Figure 3

The draw phase is split into three phases. During the Draw, every entity is called to list items it needs to render and adds the items to a display list. The list has a 64 bits key that encodes an ID and other data such as z-order, alpha-blending, material, and so on.

This is done through a ParallelFor, with each thread adding to independent sections of an array. During this phase, things like visibility culling and filling of dynamic buffers can be done in parallel.

Once every entity has declared what it wants to draw, the array goes through Sort which can be done in parallel too (although here, with entities in the order of a thousand, it doesn't make a difference). Finally, the scene is rendered, each item in the sorted list calling back the parent entity which does the actual draw calls.

Figure 3

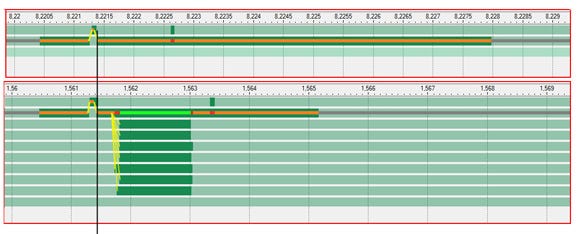

In figure 3, there are two Intel Thread Profiler captures of a release build running on a Intel Core i7 processor at 3.2GHz, at the same scale, with the task scheduler on and off. Because this is a release build, there is no annotation but the benefit of using the task scheduler is nevertheless quite clear; work is shown as green bars, with the serial case above and the parallel case below. The phase that remains serial is the render phase and it is mainly spent in DirectX and the graphics driver, with the gray line representing time spent waiting for vblank.

Figure 4, below, shows the demo in profile mode where it is instrumented to show actual work as sections in solid. This gives an idea of how tasks spread over all threads (timings are not accurate: instrumentation has a massive impact on the performance of our spinning mutex).

Figure 4

The resulting executable for this project is under 40K and if you use an exe packer, like kkrunchy by Farbrausch, it actually gets down to 16K. So, today, if you were to ask me whether you can use a task scheduler with stealing in a 64K, I can give you a definite yes!

Beyond this feat, and because I believe we need to experiment with things to really understand them, I'm hoping that this project will provide people interested in parallel programming with a nice toy to mess around with.

(For any project with less drastic size constraints, I recommend you turn to Intel Threading Building Blocks as it provides a lot more optimizations and features.)

Reinders, James. Intel Threading Building Blocks. USA: O'Reilly Media, Inc., 2007.

Pietrek, Matt. Remove Fatty Deposits From Your Applications Using Our 32-Bit Liposuction Tools. Microsoft Systems Journal, October 1996 issue.

Ericson Christer. Order your graphics draw calls around! http://realtimecollisiondetection.net/blog/?p=86

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like