The Art History... Of Games? Games As Art May Be A Lost Cause

At the Art History of Games conference, Tale of Tales, the indie studio behind The Path, argues that "games are not art," and "largely a waste of time." Meanwhile, one professor examines where art and play have collided.

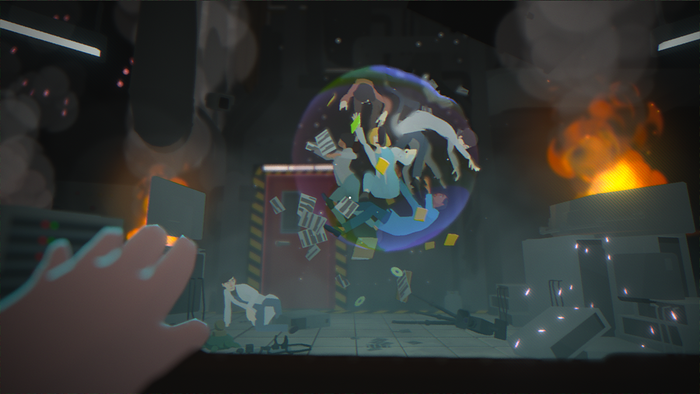

At the Art History of Games conference, Tale of Tales, the indie studio behind The Path, argues that "games are not art," and "largely a waste of time." Meanwhile, one professor examines where art and play have collided. Tale of Tales: Games "Not Art," Largely A "Waste Of Time" Tales of Tales has never been shy about making bold statements. At The Art History of Games conference in Atlanta, GA last week, Michael Samyn and Auriea Harvey, who also worked on The Path, which many pigeon hole as an "art game," laid out their case for why video games are not and never will be art, and why games are never going to evolve. "One thing need to be said first, we're not trying to not fit in on purpose," said Samyn. Instead, he maintained that they had tried to carve out a place for Tale of Tales in the game industry but room was never made for them. Samyn and Harvey listed the problems they have with games. Games, according to Tale of Tales, were not beautiful enough, or immersive enough, or welcoming enough for a large audience. Harvey announced, "some of the members of the audience are confused," as he displayed a presentation slide that boldly said: GAMES ARE NOT ART. Samyn then argued that play was driven by a biological need, and that over time play had been turned into games. On the other hand, art was not created out of a physical need but in a search for higher purposes. Unfortunately, according to Harvey, art is dead. After the rise of Modernism art has been co-opted by capitalism and restrictive forms of government. The speakers maintained that the real artists were no longer working in the art world, but instead were experimenting in the less explored corners of the internet. Samyn then dug in further, intoning, "Beside a few noble attempts, video games are overwhelmingly a waste of time." Video games have stopped evolving, Samyn continued, and the reason that games could not get their act together was that they lacked guidance. Those that controlled the game industry weren't interested in changing, they were too comfortable with the way things were. However, they said, old media that featured one-way communication was not enough. Computers offered the way forward for art, but at this point it is being held hostage by the video game industry. The speakers then switched from addressed to audience to a tone that implied that they were talking beyond the room. Samyn announced that they, Tales of Tales, could not be stopped. They would continue to take games and rip out their "stupid rules" and goals. He promised that after eviscerating games they would breathe new life into the carcass, creating something new. "Our time has come." Samyn said. Harvey responded: "Make love, not games." The two creators also announced that they were starting a project to organize all the people all over the world that were creating what they called "not games." The movement would be maintained on a series of blogs and forums, featuring conversations, screenshots of projects, as well as festivals with particular rules to guide the production of these new, 'not games'. Tale of Tales' work to date includes The Path, the unreleased project 8, its first "anti-game" Endless Forest, Fatale, and its first iPhone project, the in-development Vanitas, commissioned by The Art History of Games conference. When Art And Games Collide While the subject of art and games has a lot of discussion that surrounds it, often it's without doing the hard legwork of actually compiling a list of the different instances in which the two worlds have collided. At the Art History of Games conference, professor Celia Pearce attempted to do just that, giving a long and thorough survey of participatory and game art from the beginning of the 20th century to the present day. Appearing in several lectures beforehand, Pearce clarified the connection between the famous artist, Marcel Duchamp, and games. Famously obsessed with chess, the French artist also made art as if it was a game, often playing with constraints, such as doing on entire painting while cross-eyed. Pointing to Duchamp's readymades -- already-manufactured pieces that simply bore Duchamp's signature, including a bicycle wheel and even a urinal -- Pearce pointed out that "the procedurality of the readymades was more important than their status as objects." Touching on the Fluxus movement, Pearce talked about the composer John Cage, who would often give himself rulesets for how to perform his different pieces, even going to the extent of physically modifying the pianos he would play. A friend and collaborator of John Cage was David Tudor, who would build musical instruments out of electronic devices that were never meant to produce music. "This is playful art," Pearce pointed out, "not necessary games, but structured play." Pearce touched on more modern perspective in game design, such as the New Games Movement, which created outdoor games that were not directly competitive. She connected this to the work of Frank Lantz, the co-founder of the game studio area/code, who created games such as Pac Manhattan, in which familiar video games and types of games were scaled up to the point where they became something like performance art pieces. Parallel to the New Game Movement and Lantz's Big Games is the beginning of video game art, such as the game Alien Garden, which was designed by Bernie DeKoven and programmed by Jaron Lanier. Mods and hacks also played a huge role in early video game art. One of the first exhibitions of game art was actually an online show called "Cracking the Maze" which featured, among other pieces, the modification of different games to add female characters. Interestingly, Pearce said, at the same time Counter-Strike, a mod of Half Life that is not considered game art, was showing the mods could actually be more popular than the games they were modifying. The two perspectives on moding collided however with the game art piece "Velvet Strike", which allowed the player's gun to fire graffiti all over the walls during a Counter-Strike match. Pearce finished by pointing the audience towards latest wave of game art, such as Mary Flanagan's piece Giant Joystick. A recreation of an Atari joystick scaled up to 8 ft. 9-11 Survivor is a game that lets the player explore the terrible choices of a person trapped in one of the damaged Twin Towers. Finally, Pearce pointed to the recent and strong overlap between the art games and indie games. Works like Unfinished Swan, Gravitation, Moon Stories, and The Path, are all the inheritors of a long tradition of both art and games. This meeting of the art game movement and the indie game movement is important in bringing art games to more eyes and finding more possibilities to explore in indie games. [Charles J Pratt is a freelance game designer and a researcher at NYU's new Game Center.]

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like