Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

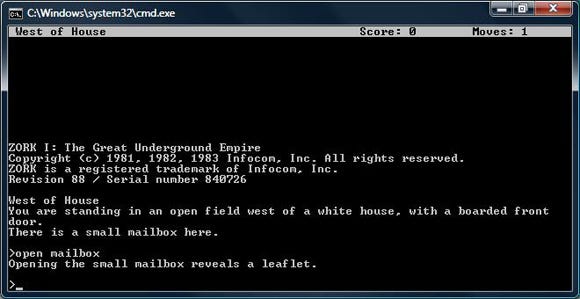

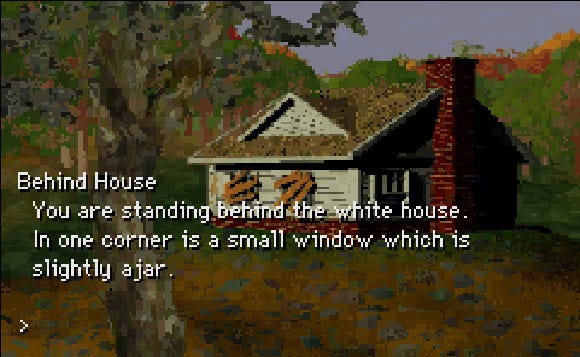

Gamasutra is partnering with the IGDA's Preservation SIG to present in-depth histories of the first ten games voted into the Digital Game Canon, this time providing a meticulous study of Infocom's seminal 1980 text adventure Zork and its unruly offspring.

[Gamasutra is proud to be partnering with the IGDA's Preservation SIG to present detailed official histories of each of the first ten games voted into the Digital Game Canon. The Canon "provides a starting-point for the difficult task of preserving this history inspired by the role of that the U.S. National Film Registry has played for film culture and history", and Matteo Bittanti, Christopher Grant, Henry Lowood, Steve Meretzky, and Warren Spector revealed the inaugural honorees at GDC 2007. This second piece takes a look back at one of the grandfathers of interactive fiction and story-based games, in Infocom's text-based classic Zork.]

Zork. For some, the name conjures up little more than a dim notion of the “primitive” era of home computing, back when graphics technology was so lacking that desperate gamers were willing to buy games even if they consisted entirely of text. For this group, the entire genre of “adventure games,” or “interactive fiction,” or whatever you wish to call it, was simply making a virtue of necessity. Gamers didn’t have access to good graphics technology, so they had to make do without it. Once the technology allowed for more “compelling” graphical experiences, of course this quaint text-only genre would go extinct. As for playing Zork today—you’re kidding, right? The text adventure is dead, kaput, deceased, expired, gone to meet the great developer in the sky. This genre is an ex-genre.

For others, though, the name Zork still makes their Elven swords glow blue. To them, saying that Zork is obsolete makes no more sense than saying J.R.R. Tolkien’s Ring trilogy is obsolete. Why do people still read Tolkien or any other novelists when there are so many movies and channels available on TV? If graphics and animation are so essential, then why haven’t comics and pop-up books long overtaken “plain text” novels on the New York Times best seller list? It isn’t difficult to see that humans aren’t exactly uniform or predictable in their preference for a given mode of entertainment. One size does not fit all, nor should it. Unfortunately, although movies and television never caused the novel to go out of production, graphical video games do seem to have caused the extinction of the text adventure. Or have they?

“The majority of people that play computer games today do not even entertain the notion that text adventure games are games at all. In their minds ‘games=graphics’; If they see a jumble of text on their screen they're much more likely to think their computer crashed than consider the possibility they're playing a game.” – Howard Sherman, President of Malinche Entertainment

“Modern gamers have seen and played a whole range of games since 1989, and of course to them Zork is a pretty strange experience; it's retro, it's hard to get into, it's not graphical. I'm pleased that people still play the games, given all the time that has passed and all the advances in software and hardware.” – Dave Lebling, Infocom Implementer

However, perhaps this is not a simple matter of cause and effect. Perhaps it’s wrong to assume that the availability of good graphics technology caused the decline of games like Zork. If “interactive fiction” has migrated to the margins of the computer gaming industry, it could be due simply to a lack of good marketing, not evidence of some inherent limitation of the genre. It’s quite possible that one day, when enough gamers are at last disillusioned with the latest 128-bit smoke and mirror show, interactive fiction titles will again enjoy the lucrative rewards won by Infocom during the heyday of the Zork trilogy. After all, the treasures of Zork are still there beneath the old white house, awaiting their discovery by new generations of gamers. Zork is not obsolete; merely under appreciated. Perhaps Zork is not the past of gaming, but its future.

“Poetry is a vibrant, essential part of American culture and many other cultures, although there is really no market at all for it. (Some companies publish poetry books, but practically no one makes a living as a poet, even if they have won the Nobel Prize.) I think IF will be a vibrant, essential part of digital media and literature even if no one manages to sell it.” – Nick Montfort, author of Twisty Little Passages

It’s quite likely that no computer game in history has ever inspired as much prose as Zork, even if we omit the billions of commands inputted by legions of over-caffeinated hunt-and-peckers. Zork and other text-based adventure games have long been the darling of academics writing about games, such as Brenda Laurel and Janet Murray.

No doubt, many of those early visitors to The Great Underground Empire felt they were experiencing the Future of the Novel. Developers and critics dreamed of a day when interactive fiction games would sit alongside their older brothers on the shelves of Borders and Barnes & Noble, and standing proudly alongside Thomas Pynchon and Norman Mailer in the reading queues of the literati. Sadly, it doesn’t seem to have happened--at least, not yet. The question is, why? What, if anything, is really beyond Zork?

No doubt, many of those early visitors to The Great Underground Empire felt they were experiencing the Future of the Novel. Developers and critics dreamed of a day when interactive fiction games would sit alongside their older brothers on the shelves of Borders and Barnes & Noble, and standing proudly alongside Thomas Pynchon and Norman Mailer in the reading queues of the literati. Sadly, it doesn’t seem to have happened--at least, not yet. The question is, why? What, if anything, is really beyond Zork?

“Zork is all text—that means no graphics. None are needed. The authors have not skimped on the vividly detailed descriptions of each location; descriptions to which not even Atari graphics could do complete justice.” –David P. Stone in Computer Gaming World, Mar-Apr 1983

“I think of them more as thematic crossword puzzles.” – Marc Blank, former Infocom Implementer

Anyone truly interested in Zork and interactive fiction will want to read Nick Montfort’s excellent Twisty Little Passages, Graham Nelson’s A Short History of Interactive Fiction, and Tim Anderson’s own History of Zork. What I intend to do here is focus less on the developmental history of the game and more on its impact, particularly on the ways it has influenced modern adventure and role-playing games.

My goal is to persuade you that the text adventure is still a viable genre for modern gamers, even in an age when software and hardware developers are making breakthrough after breakthrough in graphics and animation. I want to talk about the game developer that put its “graphics where the sun don’t shine.”

Zork began life in much the same way as many of the early computer games; that is, as a fruitful, informal collaboration by starry-eyed, college students. Indeed, it’s easy (if, perhaps, a bit misleading) to compare the development of Zork with that of another classic computer game, Spacewar!.

Zork was developed by four members of the MIT’s Dynamic Modeling Group, whereas Spacewar! was developed by members of MIT’s Tech Model Railroad Club. Both teams were excited about the possibility of computer games, and both were fueled by the adrenaline-rush of successful hacks and making a habit out of doing what others felt couldn’t (or shouldn’t) be done. However, the authors of Zork had a much different vision of the future of computer games than the hackers responsible for Spacewar!. For, although Spacewar! paved the way for graphical “twitch” games, Zork was a game for folks who preferred prose to pyrotechnics.

The authors of the mainframe Zork , Tim Anderson, Marc Blank, Bruce Daniels, and Dave Lebling, begun writing the program in 1977 for use on a DEC PDP-10 computer, the same computer used by Will Crowther and Don Woods to create Colossal Cave Adventure (Spacewar! was programmed on the earlier PDP-1). The PDP-10 was a mainframe computer that was much more powerful than any home computer of the time, though much too large and expensive for most consumers.

The few home computers that existed were so woefully underpowered compared to mainframes like the PDP-10 that most of the early game developers had little interest in trying to restrict or sell their software; if you had access to one of these behemoths, chances are you could get easily acquire games like Colossal Cave Adventure using the ARPANET, the progenitor to the internet.

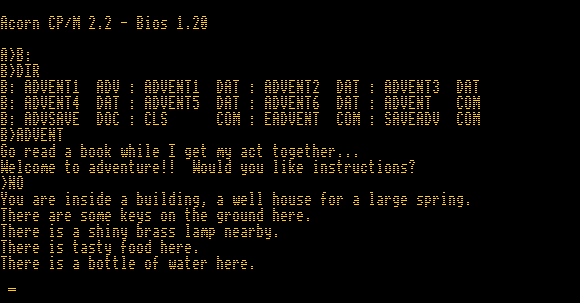

The “imps,” as they would later style themselves, were enchanted with the aforementioned Colossal Cave Adventure, also known as Adventure or simply Advent (I prefer the more descriptive title). Colossal Cave is certainly a groundbreaking game, both in the figurative and literal sense—the author and his wife were dedicated cavers, and Crowther based much of the game on an actual cave system in Kentucky. Although many critics tend to overlook this caving connection, I think it’s important if we want to fully understand the appeal of games like Colossal Cave and Zork.

Surely it is not a coincidence that both games are focused on the type of thrilling exploration one finds as a caver or urban explorer. To my mind, these games are less “interactive novels” than “interactive maps” (or “interactive worlds” to use language popularized by Cyan). Another interesting “coincidence” here is that the first jigsaw puzzle ever sold was of a map (see Daniel McAdam’s History of Jigsaw Puzzles). It seems that maps and puzzles have been associated from very early times!

Although exploration games can be rendered with graphics instead of text, this eliminates much of the freedom (or at least the illusion of such) allowed by text—a point I’ll return to later. As for Crowther, his purported intention for creating the game was chiefly as a way to share some of his enjoyment of caving and the role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons with his two estranged daughters. It’s easy for critics, perhaps avid D&D players themselves, to get so fixated on this fantasy role-playing connection that they overlook the influence of caving.

“I’ve always loved maps, and my favorite games were the ones that required me to do meticulous mapping. But I don’t think map-making and adventure games are joined at the hip; while mapping was a big part of game like Zork and Starcross, it was much less an issue in games like Deadline and The Witness, and not at all in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (which was Infocom’s second most successful game, after Zork).” – Steve Meretzky, former Infocom Implementer

“Exploration is critical, of course, but map-making was mainly required because the adventure games had no visuals. But frankly, it’s a nuisance…” – Marc Blank

“I've never drawn a map of any text adventure game I've played.” – Howard Sherman

Colossal Cave established many of the conventions and principles upon which almost all subsequent text adventures are based, such as the familiar structure of rooms and objects, inventory, point system, and input structure (“OPEN DOOR”, “GO NORTH” etc.) The game also introduced several elements inspired by J.R.R. Tolkien’s famous works, including dwarves and magic (I might note that Tolkien was always drawing maps himself). To get through the game, players frequently sketched out their own graphical maps of the areas they explored. Colossal Cave also famously introduced the “non-Euclidean maze,” or a series of identically described rooms.

The only way players can navigate these mazes (besides cheating) is to drop breadcrumbs, or objects whose placement in a room will alter its description (thus allowing the player to retrace steps). The game also requires players not merely to collect treasures, but to deposit them in the proper location to earn points (the same feature shows up in Zork). Although Colossal Cave was certainly a breakthrough, it didn’t take long for hackers to master it. Some hackers went a step beyond; they had sighted a new vista and wanted to explore its possibilities to the fullest.

Much like Crowther and Woods, the imps were initially inspired more by a desire to test their hacker skills than a singular desire for wealth. Indeed, in a famous 1979 article published in the scientific journal IEEE Computer, the authors promised to send anyone a copy of the game who sent them a magnetic tape and return postage.

This article, written by Dave Lebling, Marc Blank, and Tim Anderson, describes the game as a “computerized fantasy simulation,” and uses terminology familiar to anyone who remembers Dungeons & Dragons: “In this type of game, the player interacts conversationally with an omniscient ‘Master of the Dungeon,’ who rules on each proposed action and relates the consequences.” However, like Colossal Cave, Zork is primarily a game about exploration, involving such activities as breaking into a supposedly abandoned house, rappelling down a steep cavern, and even floating across a river in an inflatable raft. Along the way, the player is continuously confronted with puzzles and even a few fights (such as a troll to be dispatched with the sword). Most famously, though, the player must at all times be wary of the grue—a mysterious beast which lurks in total darkness, always hungry for adventurers.

On the surface, Zork appears to have much in common with its progenitor, Colossal Cave, and IF scholar Dennis Jerz has gone so far as to say that “whereas Adventure began as a simulation of a real cave, Zork began as a simulation of Adventure.” However, Zork offered several key innovations to that game, including a much more sophisticated parser capable of handling commands like “KILL TROLL WITH SWORD” and “PUT COFFIN, SCEPTRE, AND GOLD INTO CASE,” whereas Colossal Cave was limited to commands of one or two words (“GET BOTTLE”, “PLUGH”).

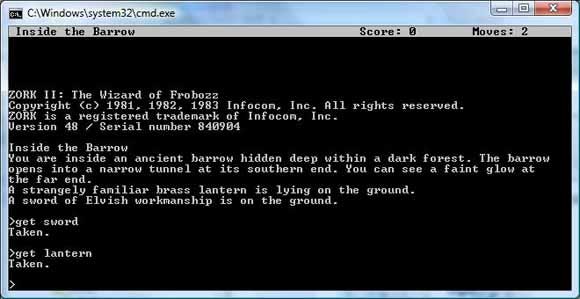

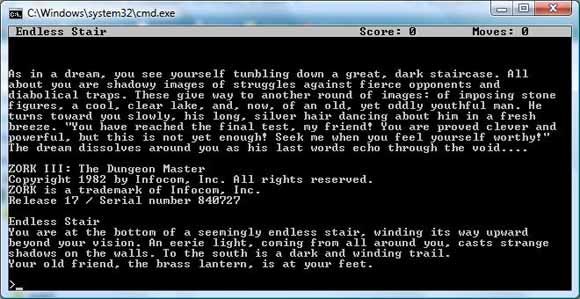

Zork also offered a more sophisticated antagonist, the famous thief, who roams about the world independently of the character and eventually plays an important role in solving the game. Zork II also introduces a coherent plot to add some narrative coherence to the player’s treasure hunting. Overall, though, the game was praised for its humor and excellent writing.

“The parser was far ahead of other adventure games and the environment was far better simulated (due to the fact that it was written in an object-oriented way). In many ways, Infocom's games were far ahead of their time.” – Marc Blank

Where [journalists and historians] tend to go wrong is to overemphasize the importance of our parser. You can't blame them for that, because we pushed it hard as a ‘unique feature’ as well. What was at least as important was coming up with good writing, good stories, and rich environments. – Dave Lebling

“Zork introduced an actual villain, the thief, who opposed the player character during the initial exploration of the dungeon, who could be exploited to solve a puzzle, and who had to be confronted and defeated. This was a real character with the functions of a character as seen in literature, not the mere anthropomorphic obstacle that was seen in Adventure.”-- Nick Montfort

I should mention that the mainframe Zork was not broken into a trilogy, but rather existed as a single massive game. After the imps founded Infocom and decided to commercially release the game for personal computers, they were faced with stiff memory limitations (and a wide variety of incompatible platforms). To get around the problem, they broke the game up into three parts, though not without some modifications and additions. It’s also worthwhile to mention the brilliant design strategy they followed.

Rather than port the code to so many different platforms, Joel Berez and Marc Blank created a virtual platform called the “Z-Machine,” which was programmed using a LISP-like language called ZIL. Afterwards, all that was required to port the entire library to a new platform was to write (or have written) a “Z-Machine Interpreter,” or ZIP. Scott Cutler took on the task of creating the first ZIP, which was written for Tandy’s TRS-80 (aka the “Trash 80.”) Indeed, one of Infocom’s key assets as a text adventure publisher was the ease with which they could offer their games on a tremendous number of platforms; graphical games were much harder to port.

“It was so (relatively) easy to write an interpreter for a new computer, and then – voila! – the entire Infocom library was available on that machine. So it was cost effective even for machines like the NEC APC (with its huge 8” floppy disks) where a game might only sell two or three dozen copies.” – Steve Meretzky

“The fact that we supported multiple platforms actually had some negative impacts, especially as the newer machines began to have more memory and better graphics. We had to write to the lowest common denominator, or spend time on each game fitting it to the different platforms.” – Dave Lebling

Indeed, for many of the more obscure platforms, Infocom’s lineup was the best (if not the only) games available. No matter what type of computer you had, you could always buy a copy of Zork. This fact no doubt offered them considerable leverage in the terrifically diversified home computer market of the early 1980s, when consumers could pick from dozens of different machines, each with its own advantages and disadvantages (cost, speed, memory, ease-of-use, expandability, software library, etc.)

Infocom also lured gamers with innovative packaging and “feelies,” or small items included with the disks and manuals. Usually these items were added to complement the game’s theme, such as the “Peril Sensitive Sunglasses” included with The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Other feelies served to curtail illegal distribution. For instance, without the QX-17-T Assignment Completion Form, players would not be able to input the coordinates needed to access the space station in Stationfall. Sadly, the ambiance achieved by the clever packaging and feelies are incapable of being “emulated,” and players really wanting to get the full experience would do well to own an original boxed copy.

“You have to mention the revolution to packaging and marketing. [Even] while the Zork games were just a manual and a disk in a blister pack, [they] were well ahead of all other software of its time, which came in Ziplock bags, often with a Xeroxed manual.” – Steve Meretzky

“Our other key innovation was to market our games to adults, but that's another, much longer story.” – Dave Lebling

The three classic Zork games are The Underground Empire (1980), The Wizard of Frobozz (1981), and The Dungeon Master (1982). Although these games are based on parts of the massive mainframe version, the imps worked hard to make each game more coherent, such as the aforementioned plot structure of Wizard of Frobozz. Now, players had to do more than just find all the treasures—they had to find a way to bring the story to its natural resolution.

No doubt to the angst of many parents worried about the “Satanism” of so much fantasy role-playing, this story culminates in giving ten treasures to a demon, who takes them as payment for performing one critical task. The game is also noted for two infamously difficult puzzles called the “Bank of Zork Vault” and the “Oddly-Angled Room.” The final game in the trilogy, The Dungeon Master, takes leave of much of the humor and opts for a more solemn and gloomy tone; one reviewer calls it “brooding.” Instead of merely hunting for loot, the player must find items that allow him (or her) to take on the role of Dungeon Master.

In 1983, Infocom released Enchanter, the first of another trilogy of games set in the Zork universe. These games were much more focused on magic and spell-casting than Zork, but retained much of the humor and excellent writing. Sorcerer (1984) and Spellbreaker (1985) round out the series. Each entry in the series is increasingly difficult, to the point that some critics complained that Spellbreaker was a contrived effort to boost sales of Infocom’s InvisiClues books.

Infocom’s Zork and Enchanter trilogies were fabulous successes, and the company followed up with several other classics (see Wikipedia for a full list). To make a long story short, Infocom’s business was booming, and its superior interactive fiction titles earned them enough zorkmids to build their own empire, not to mention throw incredible promotional parties, including the legendary “murder mystery party” thrown at the 1985 Consumer Electronics Show (CES) for Suspect. Infocom even hired a troupe of actors and let participants indulge in some “live action role-playing” to solve the murder. Infocom was at their zenith.

Unfortunately, the bottom was about to fall out of the boat. From the beginning, Infocom was not intended solely to develop and publish games (one thinks of countless rock and pop bands dreaming of producing “serious” music with the London Philharmonic). Although their text adventure games had sold amazingly well, Infocom wasn’t satisfied—they were convinced they were destined for bigger and better things. The albatross flopping around Infocom’s corridors was a relational-database called Cornerstone. Cornerstone sounded like a brilliant idea—everyone knew that database software had revolutionary potential for business, but the current offerings were far too complex for the average user. Infocom saw an opportunity, and felt that the same virtual machine strategy they used for Zork would work well for Cornerstone.

Unfortunately, by the time Cornerstone hit the shelves, the “IBM Compatible,” now known simply (and tellingly) as the “PC,” was the overwhelmingly dominant platform for business; portability was no longer an issue. Furthermore, the virtual machine setup reduced its speed, and it lacked several of the advanced features that made its rival database programs worth learning in the first place. The program was not a success, and several critics remarked that its name was apt—it sat on store shelves like a stone. Infocom had foolishly invested so heavily in the product, however, that they were unable to recover, and in 1986 the company was acquired by Activision.

What happens next is a rather dismal story indeed. Activision seemed uninterested in publishing text games, preferring instead to exploit the popularity of games like Zork in graphical adventure games, starting with Beyond Zork in 1987, a graphical game by Brian Moriarty (Wishbringer, Trinity, and later Loom).

Beyond Zork offered players a crude automap and several random and RPG elements to theoretically enhance the game’s re-playability. Re-playability is always an issue with most adventure games, since once the player figures out the puzzles and solves the game, there is little reason to play it through again—though in my experience, a few years is sufficient time to forget enough of the details to make it fun again (I compare it to re-reading a favorite novel).

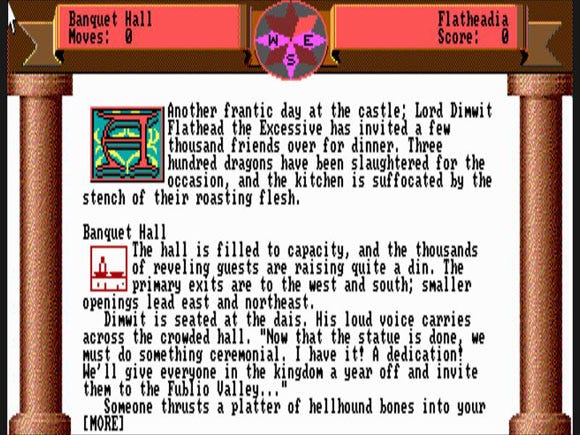

Steve Meretzky (Planetfall, A Mind Forever Voyaging) got in on the act with Zork Zero, another graphically enhanced game published in 1988. Zork Zero is a prequel to the trilogy, and offers several nice features like in-game hints, menus, and an interactive map.

“Zork Zero is a very well documented and user friendly game. Overall, it is a worthy addition to the Zork series and is, by far, the best one to date. It is a lot better than many animated ones.” – Dave Arneson in Computer Gaming World, Jan. 1989.

“Beyond Zork contains so many innovative features that if it weren’t for the richness of the text, you might not recognize the product as having come from Infocom.” – James V. Trunzo in Compute!, Apr. 1988.

The graphically enhanced Zork Zero

The last game to published under the Infocom label was Return to Zork, a 1993 game released for PC and Macintosh (and later ported to several other platforms, including the Sega Saturn and the 3DO). Developed by Activision, Return to Zork is quite a different animal than the previous Zork games, even the graphically enhanced games described above. Return to Zork will no doubt remind most gamers of the far more popular Myst, which was released a few months afterwards. The parser is gone, replaced by a purely graphical interface that is surprisingly complex and multi-faceted.

The game also offers live action sequences, including performances by Robyn Lively. Contemporary reviewers seemed to mostly enjoy the game, though Zork aficionados were (and are) divided over whether to include the game as part of the Zork canon. Very few of the original characters show up in the game, and there will always be the issue of whether any graphical adventure game could truly compare to the great text-based classics.

“People accustomed to the speed and flexibility of a text-only parser are going to feel handcuffed.” – Jay Kee on Return to Zork, in Compute!, Sep. 1994.

Activision released two more Zork-themed graphical adventures: Zork Nemesis (1996) and Zork: Grand Inquisitor (1997), quietly dropping the name “Infocom.” Nemesis offers a much simplified graphical interface and a much darker atmosphere than previous games. Like Return to Zork, Nemesis was loaded with live action sequences—to the point that the game shipped on 3 CD-ROMs.

Most reviewers remark about the intense gore found in the game, including a puzzle requiring the player to chop the head off a corpse with a guillotine. Grand Inquisitor brought back much of the humor missing in Nemesis, and seemed to pay more homage to the series than the previous two games. Perhaps more significantly, Activision released Zork: The Undiscovered Underground, a text adventure by Marc Blank and Michael Berlyn. The Undiscovered Underground no doubt eased some of the bitterness that dyed-in-the-wool Zork fans felt towards Activision, who some viewed as merely exploiting the franchise to turn a quick buck.

Most reviewers remark about the intense gore found in the game, including a puzzle requiring the player to chop the head off a corpse with a guillotine. Grand Inquisitor brought back much of the humor missing in Nemesis, and seemed to pay more homage to the series than the previous two games. Perhaps more significantly, Activision released Zork: The Undiscovered Underground, a text adventure by Marc Blank and Michael Berlyn. The Undiscovered Underground no doubt eased some of the bitterness that dyed-in-the-wool Zork fans felt towards Activision, who some viewed as merely exploiting the franchise to turn a quick buck.

Unfortunately, even a new text adventure was not enough to save Zork; Grand Inquisitor did not sell as many copies as Activision hoped. To date, there have been no more official Zork titles, though there have been several anthologies. GameTap also offers most of the games through its subscription service, but there are plenty of free (if not so legal) ways to play the earlier games online.

“Whether these games qualified as “exploiting” the brand, I guess I’d say so, but I don’t feel like Activision was sullying something pure and noble; we were exploiting the brand ourselves with games like Brian’s Beyond Zork and my Zork Zero.” – Steve Meretzky

“The major thing I would have done differently at that time would have been to try to involve the Infocom authors in the writing of the new Zorks, and to try to keep up the Infocom level of quality and polish; some of their efforts were pretty feeble.” – Dave Lebling

“When Activision was run by Bruce Davis (in the late 80's), I'm sure you couldn't find anyone at Infocom with anything good to say about them. But that's well in the past.” – Marc Blank

To say that Zork is an influential adventure game is like saying the Iliad is an influential poem. At some point, the question is not so much one of “influences” but rather of laying foundations. Although the game’s mechanics have no doubt been surpassed by later parsers, no one can deny the incalculable influence Zork has extended across a broad spectrum of games and genres. Could we have Myst without Zork? What about Doom or Ultima? All of these games borrow and pay homage, whether directly or indirectly, acknowledged or not, from the type of gameplay found in Zork.

The player is still exploring spaces, finding affordances, and overcoming obstacles. The only crucial differences are the ways these activities are represented on the screen, and the way they are selected by the player. In the first case, rooms and actions are described with text rather than graphics. In the second, players use their keyboards to input commands in the form of words and sentences rather than mouse clicks or arrow keys. For example, if the player “goes north” in Doom by pressing the up arrow key, players in Zork simply type “go north” or simply “n.” To say that the former method is objectively superior or more “immersive” than the latter seems foolhardy at best.

“Sometimes I see the same sort of humor and irreverence of Zork popping up in games, for example in some of the NPC dialogue or quest names in World of Warcraft, and I like to think that that’s the influence of Zork in particular and the Infocom games in general.” – Steve Meretzky

“The MMOs are the most Zork-like, but the lineage is more through the side door: MMOs like Everquest and World of Warcraft are descended from MUDs, which were inspired by Adventure and Zork. MMOs have genetic material from a lot of sources, though.” – Dave Lebling

“I don't discern any influence, frankly.” – Marc Blank

What Zork seemed to contribute more than anything was the idea that the computer could simulate a rich virtual environment much, much larger and nuanced than the playing fields seen in games like Spacewar! or Pac-Man. Furthermore, the game demonstrated the literary potential of the computer. Thousands upon thousands of gamers have been charmed by the wit and elegance of Zork’s many descriptions. Perhaps more than anything, though, these games offered players the illusion of total freedom. Instead of merely selecting a few set commands from a menu, Zork encouraged players to imagine infinite possibilities.

For most players, a great deal of the fun was simply experimenting with strange commands to see if the developers had anticipated them. For example, typing HELLO results in, “Nice weather we’re having lately” or “Good day.” Type JUMP, and you’re told, “Very good. Now you can do to the second grade.” On the other hand, typing “HELP” results in “I don’t know the word ‘help,’” a response which seems to have unintended significance. You can try out the results of curse words yourself.

There have been many claims made over the years (particularly by disgruntled fans of interactive fiction) that their games are simply more intellectually challenging, and that the reason so many modern gamers don’t like them is that they simply aren’t intelligent or refined enough to appreciate them. The very idea of a graphical adventure game is repugnant, fit only for dolts and small children. While I don’t share this view, as someone who teaches writing, I can certainly understand its appeal.

For what could possibly teach people the power of the written word better than a text adventure game, where typing words is literally the only way to make things happen? On the other hand, I’ve never bought the argument that a textual description requires more imagination than a graphic. It seems to me that the same sort of thing is going on in my head whether I see the word “mailbox” or see one represented on the screen. To make sense of either, I have to have some sort of familiarity with the concept of mailboxes, and imagine the possible reasons why the mailbox is there and what role it could play in the game. It’s an argument at least as old as Plato, and not one that I find very helpful.

“Graphic adventures were awful looking back in the day, but that's certainly no longer an issue. I think text adventures were simply an excellent fit for those early days of PC's, but that they simply aren't competitive now as entertainment.” – Marc Blank

“I could name a few good graphical adventures, but none that I know of suggest ways that we could reorganize our society, as A Mind Forever Voyaging does, and none are as powerful on the surface and beneath the surface as is, for instance, Bad Machine. That said, I don't object to graphical games at all, and I don't think there's a sharp divide between them and text-based IF. Text-based games can shade off into graphical ones.” – Nick Montfort

What, then, is the true advantage of a text adventure over a graphical one? For me, the answer to this question lies entirely in the perceived freedom and intelligence of the parser. It’s nice to be able to interact with a game in such a thoroughly compelling manner. And it’s here that I see the future of Zork, or the future of any text-based interactive narrative. The key is an increasingly sophisticated parser, with enough artificial intelligence to make convincing responses to anything the player might type; it would be as though there was an actual person or “dungeon master” on the other side of the screen.

It is true that such technology is far beyond what we currently have available, but consider how far graphics technology has come since 1980. What if the same level of exponential growth had occurred in Artificial Intelligence and Natural Language Processing? “The things that interest me,” writes Montfort, “are advancing the state of the art, tackling simulation and language in new ways, and doing important work within our culture.” Perhaps what we’ll find beyond Zork is not better graphics, but the wily Dungeon Master himself.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like