Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

Narrative technologies for immersive educational games

Today a person has to face and adapt to new, constantly changing forms of dialogue. This is evidenced by the growing interest in computer technologies and attempts to apply them in various fields.

Authors: Anna Musina, Pavel Zhukov

Digital gamification opens up an new unprecedented field to implement various game worlds, which, undoubtedly, can also affect the field of education. The word "gaming" obviously defines not only overall product focus, but also the presence of mechanics implemented to increase user engagement. Widely known mechanics include: accumulative systems, achievements and badges, deadline systems, etc. Each of them has long been practiced in the gamification field far beyond the digital world. Teachers in the classroom give children stickers for a job well done or offer them to play an educational mini-game with the help of drawings on the blackboard. There are a lot of mechanics used not only in education, but also in alternative business areas, but, unfortunately, it is not often possible to find examples of storytelling among them. It is important not to confuse storytelling with the role model, because although the player can take on the role inсluded in the script, games do not always provide such an opportunity.

Why using scripts in gamification is cool?

Stories are better remembered (it is much more interesting to tell classmates not about the lesson passed, but about what the characters lived through and experienced in the game);

Stories evoke emotions (thanks to the characters and plot twists, users are emotionally attached to what is happening on the screen);

Stories engage ("it's impossible to break away”, so they say about catchy movies or books, games are able to cause similar feelings);

Stories support and develop the main goals and objectives of business (scripts do not replace business goals and objectives, but, on the contrary, support them; for example, in education, a script will never replace educational material);

Stories are constantly being retold (people adore sharing stories and talk about their experiences).

Stories can be applied in any field (it doesn't matter which field the business belongs to, you can tell amazing stories in any one);

Stories are inexpensive (design of a full-fledged script can cost a reasonable price, for example, some time ago simple chatbots in the choose-your-adventure genre were incredibly popular).

In fact, the advantages of storytelling can be listed endlessly, but the most convincing, probably, is the argument previously mentioned in the article: stories are a great way for sharing experiences and making a dialogue. That is why one of the key decisions for the education project was the availability of scripts in each of the six subjects, among which there is also history.

What does a historian and a scriptwriter have in common? At the heart of both professions is the ability to tell stories. What, then, is the difference between a historian and a scriptwriter? In the use of artistic fiction. Turning to the medium of video games, we can notice how classic historical stories (commonly myths) are interpreted, quoted and transformed, for example, in the series of games Assassin's Creed, God of War, Hades and others. These examples can hardly be fully used in history lessons, because they don’t draw any distinctions between historical reality and fiction.

In this way, it is difficult for the user to separate the fiction of the scriptwriter from the truth. With this perspective, one gets the impression that there are too many scripts in the educational process, especially when it comes to humanities, where the borders between the real and the imaginary are not always obvious. History is a very romantic science and in some ways even resembles the genres of fantasy and science fiction when people, flipping through the pages of textbooks, seem to be carried back into the past imagining ancient lands and civilizations. Thanks to this experience, as well as the desire to relive it, there are video games based on historical events. Due to the emerging dissonance, a curious task appears: how to preserve historical authenticity and, at the same time, allow students to live through the magical experience of travelling to the past?

Our goal is education.

When creating a game guide on history, we followed the rules that helped us to keep historical authenticity:

Our goal is education. And all scripts created within the project should strictly stick to this purpose. Any component, whether it is a plot move, a character or an interactive element, etc. work exclusively for the child's education;

Our basis is the methodical material. The scripts were based on lectures, lesson plans, tests and assessments, as well as additional recommendations specially prepared for the course exclusively by the project's methodists;

Our way is the structuring. When creating scripts, the team created packages and mock-ups for more effective design and gamification of methodical material;

Our key is communication. Each plot element was carefully coordinated and discussed with professional historians to avoid breaking the logic and historical authenticity;

Our inspiration is love. All the teams that were involved in developing an educational project on history sincerely believed in the product.The methodists highly appreciated the professionalism of the scriptwriters and considered that high-quality scripts would help children feel and get in touch with the history.

All of the above principles helped to work as effectively as possible on the concept of an educational product on History, as well as to avoid possible inconsistencies and mistakes.

We gather here today

Each writing team within the "Education" project consisted of 3 to 5 scriptwriters and had three main positions: 1) a scriptwriter; 2) a lead scriptwriter; 3) a narrative director.

The duties of the scriptwriter were: developing the concept of the module and writing a script for it. The lead scriptwriter approved concepts, developed the interactives, communicated with methodists, as well as proofread the scripts. The narrative director approved (or issued critical edits) two main iterations of the development-the draft and the final version, carefully studying each element of the training module.

The plan of script developing usually was as such:

introduction (getting to know) to the methodical material;

writing a draft of the plot for the lesson and identifying key characters;

drawing up a detailed script map;

designing educational interactives;

creating a mock-up of the script;

editing and proofreading

Setting

History is a discourse about the past, so, when choosing a setting, we decided to allow children to plunge into the atmosphere of antiquity, carrying out a kind of time travel. The target audience of the project were fifth grade students aged 10-12 years. Such an audience is already familiar with a huge number of modern video games, among which there are such titans of the industry as Fortnite and Minecraft.

Certainly, it was not our goal to compete with the above games, but we must take this factor into account when creating our projects. Most of the modern titles take place in alternative realities, in such worlds where there is obviously a place for something incredible and a little hyperbolized. That's why we chose fiction, not realism. And in order not to "go too far", because we have to work with a humanitarian subject, we have provided game scripts with two stable tropes (a popular formula used in pieces of art, for example, a plot move): time travel and the chosen player.

Time travel

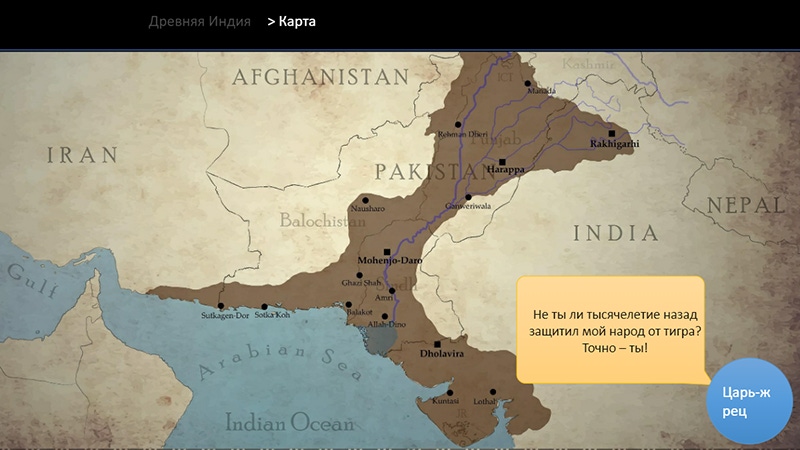

To justify the constant time travel for young players, the scriptwriters created a detailed exposition in the chapter “Introduction to history”, where the student had to help the teacher who had lost his memory, going on expeditions deep into the historical worlds for special tablets of knowledge — magical objects, studying which the historian could restore the lost knowledge. After the introduction, the student chose any of the sections of history that interested him: Egypt, China, India, the Primeval world, Greece, Rome, Mesopotamia.

The chosen player

In many games, you can find this typical character, because players really like to be special and important. We decided not to deprive the students of such pleasure, and focused on the supremacy of the user. Most of the problems that arise can be solved only by the student, and only he has incredible abilities, for example, understanding the speech of ancient deities. In the case of educational gamification, such egocentrism works for the benefit of the student, because many game actions and situations perform an educational function. In this situation, this principle worked well: “I act, I learn, I perceive”.

Game genre

It is worth paying a little attention to the conversation about the chosen game genre for all projects within the framework of “Education", namely visual novels. Visual novels are a genre of video games that come from Japan, originated from text quests, where the image (what happens on the screen), music and narration are central.

The degree of interactivity in this genre usually varies: it may not exist at all (kinetic novels) or it may include a variety of mini-games with additional mechanics in the form of, for example, "hidden object". There can be a huge number of such modifications.

Why did we stop at visual novels, as there are many other, much more “advanced” game genres, for example, adventure, shooter or RPG (role-playing game)? This is due to the technical equipment of users. The project assumed the possibility of implementation during the classroom. Unfortunately, not all schools in Russia have good equipment and the Internet that can pull the launch of a powerful application. So, educational games had to be launched via the web, without bugs and lags. The visual novels perfectly fit the given conditions.

Plot

Each lesson was accompanied by extensive methodical material, after getting acquainted with which the scriptwriters began to suggest ideas for future scripts. Certain topics were assigned to the modules, for example, religion, social system, political system, world view, etc. Based on this, the appropriate plots and characters were selected for the lesson. Here is a part of the storyboard of one of the modules on Ancient China “The Sovereign is like a boat, and the people are like water: they can carry, they can drown”:

The draft of the script included not only the plot edging, but also all the various interactive (and not so much) elements, such as: a comic book, a VN-dialogue, a mini-game and methodical material.

Pace and rhythm

Visual novels are a very static genre (due to the large amount of text), which can quickly cause boredom in a student. To avoid losing the user's attention, the team of scriptwriters carefully approached the development of the pace and rhythm of the game to maintain the balance between study and entertainment. To do this, interactives were applied and all the possible ways of presenting the material were tested.

Comics

Comics became an excellent solution for adapting methodical content. At a later time, they were finalized with the help of editing, creating the effect of a rapidly changing picture and constant dynamics, so as not to let users get bored.

VN-dialogue (visual novel dialogue)

This way dialogue situations with characters were called. They were performed in the form of special windows with the avatar of the character on the screen. Each of these situations was seriously designed from the point of view of content — we made sure that the amount of text didn’t exceed a certain number of characters, so that the characters reacted differently to what was happening, their emotions were read, so that they could approve or not of the user's actions, and also that the conversations weren’t delayed and interrupted by interactivity.

Mini-games and interactives

The scriptwriters worked on the concepts of mini-games and interactives as part of the history project. Great attention was paid to tactility and the idea of user’s participation in the game process. For example, in one of the mini-games, students were offered to partake in an ancient Egyptian procession called Opet, marking the correct route on the map and, as if physically taking part in it, at the same time assimilating methodical material.

All the developed interactives were natively integrated into the methodical material, complementing it in their own way. To achieve this result, the team had to abandon the idea of unification of mini-games, most of them were developed here and now, for the needs of each individual element of the module. For example, students could:

make their own papyrus;

study the schedule of the pharaoh's day;

save the villagers from a sandstorm;

participate in an archeological dig;

draw maps of the area

and much more.

Methodical and script maps

As the lessons and scripts were distinct by a variety of content, it was important not to lose the content and not to get confused in it. For this purpose, special maps were designed: methodical and script ones. In the methodical maps, the chronology, the logic of the action and the route of the user were laid, and the artistic and game elements were built up in the script ones.

The methodical map looked such as:

Which was then transformed into a script map:

The basis was a serial structure consisting of several story arcs. The plots on the subject of history were linear with the possibility of choosing a sequence of scenes and tasks. That is, basically, the idea was traced "one lesson = one plot". The methodical material itself and the classroom education system were based on the flexibility of passing by the user. There were recommendations on how and in what order to take lessons, however, children could also decide independently. So, the scriptwriters couldn’t make a global plot for the whole subject of history. Experiments with non-linearity were allowed in other projects of "Education".

The storylines were linked by one key character, and the player's aim was to resolve some conflict during the game action: someone stopped believing in his divinity, someone couldn’t decide on the choice of a life path, someone was kidnapped by a Chinese dragon ... There are a lot of scripts! At the same time, all the conflicts were unique, and no one lesson was repeated by another. Everyone learned something new about both the characters and the world of the game.

Characters

About fifteen characters were created for each section of History. Such an extensive number of actors allowed us to build diverse scenes and maintain a sense of novelty among users. The study of the characters was given a significant role, as it was the character who acted as the mouthpiece of the methodical material. The archetypes of “friend” and “mentor” were taken as a basis, and their representatives met in many modules.

Ideologically, the scriptwriters tried to avoid negativity in the plots and personalities to create a pleasant impression of the educational process. In every possible way, the idea of education as a communication between a teacher and a student was pushed. The teacher is a friend and assistant of the student, and not a strict adult who forces him to do something that he doesn’t like. Conflict situations mostly arose from natural antagonistic forces, for example, natural disasters, or from historical situations, such as wars. So the antagonist was a rare character.

A special profile was developed for the characters. The scriptwriters tried to avoid the concept of "talking heads'' which is quite popular among gamified projects. A "talking head" is a character who doesn't have a personality, introduced into the project only to express business goals. In the case of education, such characters explain exclusively methodical material to the user without emotional coloring, own assessment and cause-effect relations.

The profile helped to make the character deeper. Each of the characters had their own goals, problems, personality and background. The life of the characters was built separately from the player, in other words, when writing scripts, the scriptwriters asked themselves the question "How would he live if it wasn't a game?”. The profiles of the characters included the following information:

description (a brief description of what kind of character, what role does it play in the plot and worldbuilding);

appearance (description with references of the appearance of the characters);

biography (background, what happened to the character before he met the student, causal relationships);

goal (what the character wants);

personality (traits of the character);

the manner of communication (how he talks and communicates with the player comes from personality);

features of speech (the scriptwriters tried to make the characters' speech diverse, someone burrs, someone stutters, someone constantly shouts);

distinctive features (what sets him apart from other characters);

foible (which doesn't do the character well) etc.

The result of filling in the profile was short descriptive cards.

She comes from a noble family, the fourth child in the family of a military commander. The two older brothers have followed in their father's steps, the older sister is preparing to get married, and Lin is in a sense left to herself. She spends most of her time with her grandfather, who, seeing a certain potential in her, teaches Lin sciences equally with his students. Lin is active, curious and friendly; absolutely forthright; quite self-confident, but not without reason; worried about family relationships; problems with identifying her own future; player's attitude — (friend); likes to be bossy. |

Many characters had their own prototypes, such as the guide to the culture of the nations of Mesopotamia - Oan (or Oannes, or U-An) - according to the legend of the Sumerians, a character with the head and body of a fish, but with human legs (and with a human face), who came out of the Persian Gulf. The characters were created through a thorough study of the methodical material to avoid historical inconsistencies and not to assign irrelevant traits to the real character of antiquity.

Mockups

A curious feature of the project's production was the design arrangement of scripts. In most companies, scriptwriters work with wiki-documents or with Google docs, in the case of “Education”, they had to create complete mockups (fake shots) of screens with the placement of characters, objects, interface elements and the text in the presentation format (. pptx).

Despite the obvious increase in script development time (the average script size was from 100 to 200 slides), this format helped to visualize what was happening and avoid further misunderstandings on the part of different departments. The scriptwriters could more accurately convey their own ideas.

Mockup of scriptwriters:

The final version:

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like