Road to the IGF: Zachtronics' Eliza

Seumas McNally Grand Prize-nominated Eliza puts therapy in the hands of an AI, using algorithm and data to attempt to solve humanity's problems and asking what problems will come of this.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. You can find the rest by clicking here.

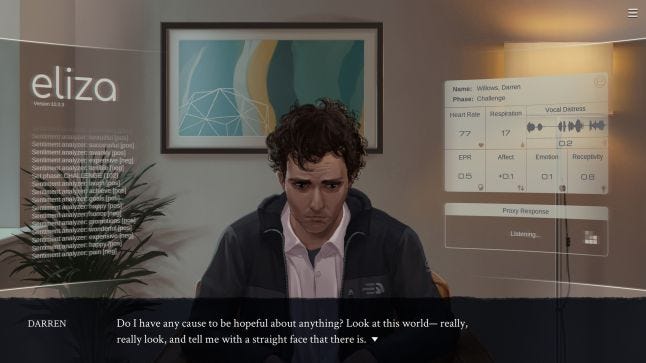

Eliza puts therapy in the hands of an AI, using algorithm and data to attempt to solve humanity's problems. You'll put this program to use as Evelyn, reading from a script as you try to help people with it. Is a chat program, complex as it may be, enough to fully comprehend what people go through in their challenging lives?

Matthew Seiji Burns of Zachtronics, developers of the Excellence in Narrative and Seumas McNally Grand Prize-nominated game, sat down with Gamasutra to discuss the real-world programs and chatbots that have been designed to handle therapy, the difficulties that can come from relying on technology to solve our emotional and mental health issues, and why the visual novel format was the perfect way to explore this kind of story.

AI Explorer

My name is Matthew Seiji Burns. I conceived, designed, and wrote Eliza, directed the voice actors, composed the music, and did the sound design.

As for my background in games, it’s a long story! The short version is I’ve held lots of different roles at many different places, from big-name studios to academia to indie. Currently I handle audio and narrative at Zachtronics. I also make small personal things on the side such as Twine games.

Virtual therapists

Most of my ideas kick around for a long time, but this one had a specific point of inspiration. In 2014, I was working at a major university in a lab that used computer games for research. As part of that job, I had to attend certain research conferences, and there I would be exposed to the research that other labs around the world were doing.

One of these research projects was an experimental “virtual therapist” program. This research was funded by DARPA, the technology development arm of the US military. The idea was that the system could screen returning American soldiers for PTSD using a combination of computer vision, real-time analytics and virtual human avatars, and maybe help them open up or otherwise serve as some kind of initial first responder for mental health problems. Something about that was very striking to me and I couldn’t get it out of my head. I kept thinking about some young kid who enters the military, deploys, faces truly awful situations and gets PTSD, and then has to talk to a computer about it because nobody wants to spare an actual human being for them. Needless to say, it felt really dystopian.

To be clear, this was simply a research prototype and has never actually been rolled out, as far as I know. But when I got back home and looked into the topic further, I learned the concept was hardly limited to a single research project at a single lab. Mental health is an increasing concern across the globe, so technologies that could be used to address it are a huge area of interest. Universities, big tech companies, and startups alike are developing techniques to attempt to, for example, determine your emotional state from the way you speak or move your body.

I found several venture-funded apps that are basically chatbots for mental health which use an instant message-like interface to attempt to get users to reframe negative emotions and otherwise support their wellbeing. And, as the years went by, this trend intensified. In 2017 the Apple App Store noted, “never before have we seen such a surge in apps focused specifically on mental health, mindfulness and stress reduction.”

As someone who works in a technology-forward industry, and who has sought care for my own mental health, including therapy and medication, I couldn’t help but feel intrigued, and yet also alarmed, at how fast and how deeply we’re committing to applying the tech company mindset, and accompanying toolset, to the complex issue of mental health.

So, I thought about this idea for a long time (about five years), going through a number of prototypes and iterations, which I’ll describe in some detail below.

Means of exploring a complex subject

I prototyped some early ideas for the game in Twine. The dialogue scripts were composed in Google Docs, then later brought to Google Sheets for importing into the game. I kept track of the status of all scenes and laid them out with Trello, using one card for each scene, message, email, etc.

Dialogue editing, sound design, and music composition were done with Logic Pro. The characters, backgrounds, and interface elements were designed and painted in Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Animate. The game code itself is written in C# with Visual Studio.

On what drew them to create an interactive narrative about the intersection of human emotion and AI analysis

The first part of the question is, I think, why the story of Eliza needed to be an interactive narrative in particular. Why couldn’t I have written, say, a novel or film script that addressed these same topics? As I was experimenting with different ways to engage with the subject matter, I kept coming back to the idea that the person needed to feel like they were there in the counseling room, and not simply watching the story unfold from afar.

This isn’t to say that written stories and film can’t draw you into their world— they absolutely can and often do. But an interactive piece has a certain quality to it that puts the player in the driver’s seat of a scene, even when they’re just navigating through a space or clicking to advance to the next line. If you imagine a therapy scene in a film versus the first-person therapy scenes in Eliza where you are ostensibly responsible for the client (even though you have no choices to make, which we’ll get to later), there’s a clear difference in those experiences and the way each of those things feel.

As for the other part— the intersection of human emotion and AI analysis— the analysis part comes from my time working in academia and seeing computer science departments apply their very specific set of approaches to literally every problem in the world. I’m not saying there haven’t been advances as a result of this, but at the same time, when all you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. I watched machine learning applied to anything that could be quantified in some way, which is to say basically everything. Education, medicine, language, behavior, emotions... everything. And this has been going on for a long time, right? I just didn’t realize the scale of it until that point.

Exploring the challenging topic of AI therapy

I’ll break this into three threads: research, personal experience, and imagination.

The research thread is, I think, the biggest one. I reached out to and spoke to mental health counselors about the job and what it entails, and this is where I learned just how much the profession is increasingly dependent on metrics. If you’ve sought help for mental health recently, you might recognize what I’m talking about: You’ll be asked to rate how you feel on a scale from one to ten, maybe with a bunch of other Likert scales and yes-or-no questions. “Have you felt this way in the past three weeks? How many times did you feel it?” On and on and on. Your “score” on these tests will ultimately decide your diagnosis and your care.

You can easily see how this practice might fail to account for extenuating complexities (what you might call the humanity) of the situation. Yet representing “mood” on a one-dimensional scale of ten integers is so common and seemingly accepted today that it’s easy to see why folks with computer science degrees felt they could easily make big strides in the field.

Another aspect of real-world mental health care is the way it’s become more scripted and rote. I reviewed some modern counseling training material for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and other methodologies, and some of these manuals literally go, “At the start of the session, say the following sentences. Then, if the client says X, say Y,” and so on. I recently spoke with a veteran counseling psychologist who was very much against this trend and told me that in fact, recent meta-analyses support the idea that the best predictor of success in therapy is not the specific intervention at all, but how well the counselor and client get along.

Then there is ELIZA, the original chatbot created by MIT professor Joseph Weizenbaum in the 1960s. The more I read about it, the more important it became to the game’s story, to the point that eventually I named the product in the game, and consequently the game, after it. The thing is, ELIZA was meant to show that computers did not have to actually understand human speech in order to convincingly mimic it, at least for a certain kind of limited conversation. But the message was lost in the noise of technology zealots who pointed to ELIZA as evidence that computers were becoming intelligent and that generalized AI - “strong” AI - was soon on its way. Even Carl Sagan, writing in 1975, predicted that computerized therapy would become common, delivered through “a network of computer psychotherapeutic terminals, something like arrays of large telephone booths.”

Weizenbaum was actually dismayed by the reception of ELIZA, and for the rest of his career operated as a kind of lone, cranky skeptic against the numerous professors only too eager to work with the military industrial complex during the Cold War to develop computer technology for military applications. His book Computer Power and Human Reason (1976) sounds a note of dissent on the technological triumphalism of its day and argues that, even if a future computer did become powerful enough to perform psychotherapy, it would still be morally inadvisable and vastly preferable for a fellow human being to do it.

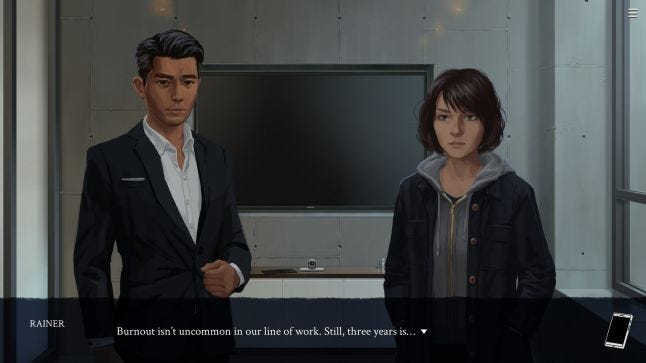

The second thread is personal experience. Our protagonist, Evelyn, has experienced some pretty bad burnout before the story begins, and while I don’t want to place too huge an emphasis on my own life here, I would be lying if I didn’t say that wasn’t influenced at least partially by my own experience being crunched very hard on big triple-A games throughout my twenties. When I started in games, I simply didn’t know any better, and harmed my physical and mental health working until the early hours of the morning trying to get builds out in order to ship games on time, and all of that in order to make a few executives and stockholders happy (and players, too, sure, but let’s not kid ourselves too much about the primary reason the industry exists in the form that it does). Why did I do that? That’s a common question when wrestling with burnout. Why did I work so hard? What was the point?

Another personal experience that affected the story is how I sought treatment for my own mental health problems, as I mentioned above. Overall, my experience with counseling and therapy has been positive, though it’s difficult not to see some of the weaknesses in the system and other ways the process can be awkward. Rob Zacny at Vice mentioned this when he wrote about the game, that even human-to-human therapy sessions can have this stilted, strange feeling to them. You might find yourself telling a complete stranger things you wouldn’t tell someone you’ve been dating for years, which is odd if you think about it... yet also perfectly understandable. It’s weird.

The third thread is imagination— specifically, trying to get out of your own head and into the heads of your characters. That’s a skill that, as a writer, I’ve tried to develop. I wanted every character to have some depth and weight, both the people who Evelyn speaks to about the past and her job, as well as the therapy clients who come in to speak with Eliza. This was important to the game because I feel that, too often, we talk about technology and policy in the abstract and lose sight of the real people that these decisions affect. Part of the reason you do so many therapy sessions in the game is so you can see that these are actual people (actual fictional people... which is its own thing we talk about below).

The strengths of the visual novel format in conveying the themes of Eliza

The strengths of the visual novel format in conveying the themes of Eliza

Visual novels sometimes come under criticism for the perceived fault of not being interactive enough or not having lots of moment-to-moment choices. But the ostensible weakness of any format can also be its strength, and the seemingly restrictive framework of a visual novel is also perfect for encapsulating the experience of someone who’s trapped— someone who is being pulled along in life by obligations without exercising much control. That’s why, even though I didn’t have a specific format in mind when I began thinking about telling this story, I gravitated toward using the well-developed grammar of visual novels to do it.

The visual novel format also dovetails nicely with the guided therapy sessions, which are the heart of the game. Some players immediately understand they have no control over the rating they get after the session is done because they couldn’t make any choices, but for others, it takes a little while to become apparent. I have earlier prototypes of the game where players specifically select what to say to the client, which results in their feeling better or worse, and ultimately this didn’t sit well with me. It would make the procedural argument that, if you just said the right thing to people, you could help them… as if certain people with problem X just need to hear sentence Y and they’ll be better.

The more I thought about interpreting therapy as a gamelike system, the less I wanted to do it. Every character in my story is a full person, an irreducible whole with situations specific to them and only them. Furthermore, to imply through game design that counseling can indeed be successfully performed by an AI as long as it is guided by a human was not a statement I wanted to make.

The other way the structure of a visual novel helped the overall storytelling is the way the game only opens up at the end. This was another deliberate choice on my part, and it’s because I think choices are most interesting when placed in lots of context. What a long period of linearity does is allow me to set up a complicated situation, inside of which seemingly simple choices can grow more rich and meaningful. I think this might be more true to life than a system that provides many small choices that you must be consistent with in order to steer the narrative in a certain direction.

I spoke about this at the Design Microtalks at GDC in 2019. I was working on the story of Eliza at the time, so if you watch the talk now, you can see how my thinking on it was put into practice with the game.

Questions naturally coming from good stories

My first concern was simply to tell a good, relatable story. To me that’s more fundamental than posing any given question specifically, because to me, the questions come naturally as a result of having a real story. Hopefully, the question of what Evelyn should do doesn’t feel theoretical or abstract because of the people she’s spoken with and the therapy clients she’s met. Her decision is tied into all of these other things— systems, society, individual human beings. Plus, even though the game only asks you what Evelyn herself should do, she’s just one person. There are larger questions lurking in the background, like what our society’s relationship to technology should be versus what it is now. Things like that.

Even after all that, though, my primary purpose wasn’t to pose questions about big issues. My primary goal was to reach players who connect with the story, who feel seen by it.

Real-world concerns

Because I live in Seattle, there are a lot of Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook, and Google folks around. One night I was at a social event chatting with someone who said he was a software engineer for Amazon. I described the premise of Eliza to him by saying, “Imagine Amazon added a talk therapy function to Alexa.” And he said, in this very matter-of-fact way, “Oh yeah, we’re working on that.” I don’t know if he was making some kind of deadpan joke, but it’s certainly imaginable that they would do this, especially since we already know about their interest in discerning an Alexa user’s emotional state.

Eliza is set in the real world and in the present day. Even though I described that demo I saw that inspired it as feeling dystopian, I doubt anyone involved in the research had cartoonishly sinister agendas or evil motives. It wasn’t a smoky dark room. It wasn’t pouring down rain at night with pink and blue neon highlights on things. It was a beautiful warm and sunny California day, not a dystopian feeling at all. That’s why I ultimately decided not to go in a cyberpunk or science fiction direction with the setting, even though I toyed with it at the beginning. I feel like the most cyberpunk thing you can do today is accurately describe what’s happening in the world.

On whether games can open us up to complex subjects

Albert Camus famously wrote that “fiction is the lie through which we tell the truth,” a sentiment you can find echoed by many other writers. I think fiction, and by extension games, can indeed cause people to consider the world in a way they haven’t before. At the same time, it’s not that common an occurrence. As is the case with any other type of entertainment media, the majority of people who play games would rather pick one that is designed to maximize pleasure. By necessity, something focused on being entertaining has to prioritize its capacity to delight, and has less room to try to encapsulate a complex topic or challenge a worldview.

Still, yes, it is possible. A couple years ago, I wrote about games and art (for this very site!) where I claimed that “games” are better thought of as a set of tools and techniques as opposed to products on someone’s shelf or hard drive. I’ll go further today and say that games are a language. Games have a vocabulary and a grammar. Because of this, you can use games to do anything a language does— amuse people, inform them, make an argument, tell a story, create a world to spend time inside. You can get at the truth, and you can lie, and you can lie to get at the truth. You can be subversive or reverential, cynical or euphoric. All of these things are possible in the language of games.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like