Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra talks to Mother 3 fan-translator Clyde 'Tomato' Mandelin on the unofficial translation of the Nintendo classic, his day job in translation, and his localization heroes.

[In this in-depth interview, Gamasutra talks to Mother 3 fan-translator Clyde 'Tomato' Mandelin on working on the unofficial translation of the Nintendo classic, his day job in translation, and his localization heroes.]

"We know what we're doing isn't 100% legal. But even so, we try our best not to step on companies' toes. In fact, I've received a number of e-mails in the past from professionals inside major game companies giving their thanks, offering to buy me drinks sometime, stuff like that. What we do is appreciated, but in a hidden way, I think."

Clyde Mandelin is a Japanese-to-English translator. As a professional, he's worked on video games such as Kingdom Hearts II and Tim Burton's The Nightmare Before Christmas as well as a slew of well-known anime series including Dragon Ball, One Piece, and Lupin the 3rd.

But just as notable is Mandelin's work on lesser-known games, all of which he translates in his free time and without payment.

You see, Mandelin is a fan translator, one of a niche but revered group of game fans who hack into those 8- and 16-bit Japanese video game treasures that never saw a Western release, translating them into English before finally releasing a patch onto the Internet.

Using this patch, gamers can play the game in English via an emulator, experiencing those forbidden fruits previously withheld from Western eyes.

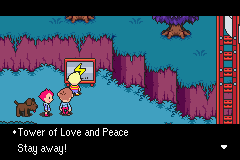

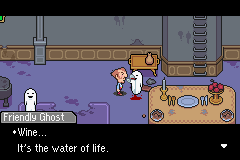

In this underground world, Mandelin is better known by the moniker, Tomato, and it's thanks to his work that RPG fans have been able to play Square and Enix titles such Bahamut Lagoon, Star Ocean and, most recently, Nintendo's Game Boy Advance sequel to fan-favorite Earthbound, Mother 3.

The latter title attracted a huge amount of attention this autumn; the translation patch receiving over a hundred thousand downloads in the first week of release.

"Yeah, it was definitely a nice surprise," he explains. "The response was a lot bigger than we expected, and it was awesome how excited and positive everyone was during the project. I originally thought we'd get a couple dozen thousand downloads total, but we quickly passed the 100,000 mark after the release. With off-site mirrors and such, the real number is probably like double that. When I think about that, I'm just like, 'Damn.' It's really cool that this little project on the Internet could make so many people happy."

Mandelin's in his twenties and works for FUNimation and Babel Media, the popular game localization agency. When he was a boy, he lived in Hawaii, an experience that he believes sparked an interest in Asian culture and language.

A gamer since the Atari 400, it was playing Japanese-developed Super Nintendo titles like Earthbound and Chrono Trigger that first inspired Mandelin to mess about making his own games. But it wasn't until he was leaving college that he decided what he wanted to do with life.

"I had absolutely no idea what I really wanted to do with my life after graduation. I would switch majors and still not be happy, so I eventually decided take out a loan and spend a year studying in Japan to get out of my rut. It was an expensive gamble."

"While I was there, I heard about some ROM hackers who needed help translating scripts, so I offered my services. The first day I started, I instantly knew I wanted to do this for a living, and after that, it became a kind of quest to constantly improve my skills. That feeling of finally knowing what you want to do is so good."

Mandelin fell in with the ROM-hacking scene just as it was gaining momentum and notoriety. The gigantic worldwide success of Final Fantasy VII had broadened the JRPG audience significantly and, with a relatively small library of English language titles to consume, many hobbyist fans were looking longingly at SquareSoft's large Japanese-only back catalogue.

Before ROM hacking took off, English-speaking players of these titles would have to print off hardcopy fan translations and try to follow the on screen text as they played. But emulation changed all of that.

Soon, small communities sprang up, bringing together hackers and translators who would work together to extract the text from the ROM and replace it with an English script.

"There are basically two major parts of a ROM translation, whether it's for the SNES or any other system: the hacking part and the translating part," he explains. "First, the hacker has to locate the game's font and produce what's called a table. Using this, the hacker can then start to locate the text data."

"Once it's been found and figured out, the hacker can then dump the Japanese text to a file. The translator then takes this file and translates it. The translator usually just types the translated text using something like Notepad, but for really big projects, the hacker might create a custom program to make it easier on the translator."

"Sometimes, a person adept at editing/revising is brought in to smooth the text out afterward. Meanwhile, the hacker alters the existing font to have English letters if the font didn't already have any. The translated script can then be inserted back into the game. Of course, it's all a lot harder and takes a lot more time than that overview suggests, and the process can vary greatly from game to game and person to person."

The practice of ROM hacking, like emulation itself, occupies a grey legal area. In strict terms, it's a case of third parties tampering with companies' IP. But that's not to say there isn't an ethical framework holding up the scene.

"First and foremost, ROM translation is a hobby, not a way to earn money or stick it to the man," he says. "As an example, the central hub for ROM hacking and translating, romhacking.net, won't post translations for recent games, and in some cases, like with the Mother 3 project, we were fully prepared and willing to stop our work immediately if there had been any word from the game's IP owner."

"In general, I think all respectable fan translators know exactly what they're doing, and only work on translations out of love. I think companies (or at least their legal departments) understand this, and it's this mutual understanding that has kept ROM translators free from cease-and-desist letters."

Perhaps this is true for purely amateur ROM hacker fans, but we wonder whether those who try to make the jump from fandom to professional translator might be encumbered by this kind of shady past? "I don't think any of the unofficial work I've done has ever been a hindrance to my career. ROM translations and other unofficial translations were actually a step in my goal of doing this for a living."

Perhaps this is true for purely amateur ROM hacker fans, but we wonder whether those who try to make the jump from fandom to professional translator might be encumbered by this kind of shady past? "I don't think any of the unofficial work I've done has ever been a hindrance to my career. ROM translations and other unofficial translations were actually a step in my goal of doing this for a living."

"The experience I gained from years of this work definitely helped when it came to step into the professional world. Some of the side skills I picked up along the way were also key in me being where I am today. Things like knowing how subtitle timing works and already being familiar with certain kinds of software helped immensely."

"It's been interesting for me, being on both sides of translation. A lot of times, people will say, 'Fan translators are better than professional ones!' But every pro translator I know is/was a fan translator on the side too. Aside from some of the logistics, fan translating and professional translating are almost no different. Probably the biggest difference is that you have deadlines with professional translations. And sometime they're very intense. In one case, I had two days to translate an entire Wii game. That can affect quality sometimes."

"Also, with a professional translation, you usually can't fix any mistakes. So if you make an error or a typo (perhaps due to a tight deadline), it'll be out there in the public forever for fans to pick apart. With fan translations, you can always make revisions and release new versions easily."

"In a professional setting, you also have someone to answer to. That's not necessarily a bad thing, because it means you can get lists of official names and things like that, which help a lot. If you're really, really lucky, you might even be able to communicate with the creator of whatever you're working on to get clarification for things."

"With fan translation, you're free to do whatever you want. Sometimes that freedom makes fan translating less stressful than professional translating. For instance, if you have an official list of names, but there are obvious mistakes in the names (as often happens), you have to go through tons of red tape to get things fixed... and sometimes you can't get them fixed anyway. A fan translator, working on the same thing, could ignore all that and use the obviously correct name."

When Mandelin first started working in fan translation there was a huge array of unreleased Super Nintendo gems to work on. Ten years on, most of the classics have been excavated and released. So where next for the scene?

"Sure, most of the big-name Famicom and Super Famicom games have been released in the West, either by the fan scene of the publishers themselves. But the translation scene is slowly moving into the PlayStation, Game Boy Advance, and PlayStation 2 realms, and there are certainly plenty of treasures to be found there."

"DS games seem to be a little easier to modify too, so that may be another source of great, undiscovered games down the road. I get the feeling that things are only going to pick up from here."

We wonder if spending so much time translating from one language to another spoils the experience of other Japanese releases that he encounters in English?

"Yeah, whenever I'm playing a translation or watching something, I'm always on the lookout for new ways to translate phrases so I can improve my own translation skills. I even used to keep a notebook of neat translations for certain generic Japanese phrases."

"I also often try to imagine what the original text was by working backwards from the translation. It's a fun language game in itself. But unless I've played a game in Japanese already, I can't really say if a certain translation is good or bad."

With that in mind who are Mandelin's heroes, those translators whose work inspires him in both his amateur and professional work?

"I'm a huge fan of Alexander O. Smith's translation work (Smith often works with Square Enix and translated, amongst many other titles, Final Fantasy XII). I can only dream of ever being on his level. To this day, I can't get over how good Vagrant Story's translation/localization was."

"Of course I also greatly admire the skill of Nintendo's Treehouse. The way they're able to make text flow so smoothly is a real sight to see and often the translation is imperceptible in that players wouldn't know it was originally written in Japanese. I'm also a fan of the Disgaea series, and I liked a lot of the little localization choices Atlus made there."

"Of course I also greatly admire the skill of Nintendo's Treehouse. The way they're able to make text flow so smoothly is a real sight to see and often the translation is imperceptible in that players wouldn't know it was originally written in Japanese. I'm also a fan of the Disgaea series, and I liked a lot of the little localization choices Atlus made there."

"I have to mention Ted Woolsey (Squaresoft's translator during the company's Super Nintendo heyday), of course, because he really upped the bar for game translations."

"Even though people give him a lot of flak nowadays, I can still remember being amazed at how much better Final Fantasy III read than Final Fantasy II did."

[Check out Clyde's personal site, where there's a list of the games and videos he has worked on in both a professional and fan capacity. The Mother 3 development blog, which outlines all of the difficulties the team had to content with in bringing the game out in English, can be found here.]

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like