Wrangling the grand, interstellar ambitions of Jett: The Far Shore

"Within the context of what has shipped this campaign -- there's too much happening."

This interview has been edited for clarity

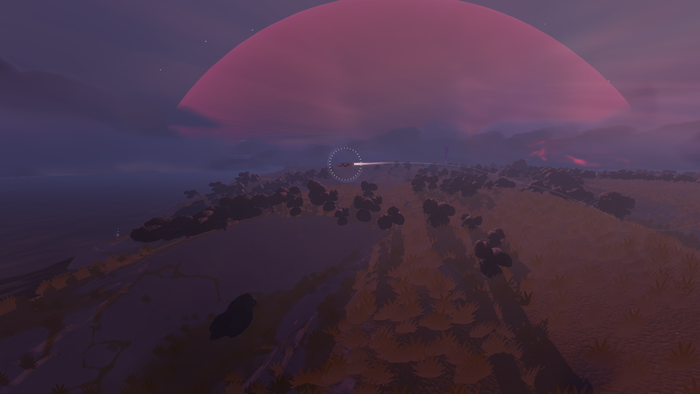

Jett: The Far Shore can be an intense, almost overwhelming experience. The atmospheric adventure signposts that early on, luring players in with a hair-raising crescendo of a tutorial that sends them hurtling into the eternal unknown in search of a new home.

From there, the cosmic yarn unfolds across segmented acts that combine planetary exploration, action set-pieces, existential narrative beats, intricate flight mechanics, environmental puzzles, and touching moments of spiritual introspection.

As as a player, there's a lot to wrap your head around both thematically and mechanically, and in many ways that Jett's greatest strength and most notable weakness. Much like the titular Jett -- a scout craft capable of speeding across the landscape like a hypersonic missile -- the game soars and plummets with carefree abandon as it strains to combine those elements into a cohesive whole.

That colossal sense of scope was something Jett creative director and Superbrothers A/V founder Craig D. Adams wrestled with throughout production, and during a candid interview with Game Developer, the veteran designer admits he never quite found the sweet spot. "Within the context of what has shipped this campaign -- there's too much happening," says Adams, who accepts there are times where the team's reach exceeded their grasp, although there was at least a consistency to that sense of ambition.

"[By 2015] we had built out the campaign in a really clunky way, and what we wanted to do is get to the heart of when this game is really in its groove -- whatever its groove is going to be -- what are you up to?," asks Adams. "And so that's where it's like 'well, what happens if you take Motorstorm: Pacific Rift and Monster Hunter, and you somehow get them to fit?'"

Adams emphasises how many of Jett's core mechanics -- including the more interactive tools like the torch and grapple hook -- have been cemented in place throughout production, and that as development progressed it was more about adding polish and bringing them into focus. As such, the mammoth scope of the project remained fairly consistent, but that imposing sense of scale also surfaced feelings of uncertainty.

"We decided we're gonna stick with the light too. We're gonna do the grapple tool that you can shoot. And, yes, you're going to be scanning, and of course you can collect things. All of those verbs were in there. But it should be said that neither (Jett co-creator) Patrick McAllister nor I have like a video game design qualification on our wall. So we were kind of faking all of this stuff based on what it felt like the game wanted to be. It was also just the two of us, and we didn't have the rigour to take a mechanic and drive it far enough that you could really get a grip on it," continues Adams.

"So we would push things pretty far and then be unsure. One thing that we had back then was a focus on crafting that allowed players to learn about ecosystems by picking things up and combining them. But we got out of our depth with that, and it also felt against the grain for the kind of more laid back cinematic experience that Jett was turning into."

To bring that smorgasbord of concepts into focus and give the project a clearer sense of direction, Adams pulled together a team of contributors and consultants. He acknowledges that until those voices came into the fold, what he and McAllister had created was still fairly nebulous and "floppy" -- although it was possible to see the intent behind the design. Those fresh eyes helped Adams tighten the screws and steady the ship, but there was still a lot of work that needed doing, especially in terms of actually communicating Jett's chorus of ideas to players.

"We liked so many of the ideas that we had put in, but they were mind-boggling to wrangle because we had to layer in so much player communication. Everything is bespoke and distinct and strange -- even the mobility takes player communication. I would say we felt like mobility wasn't encouraged or supported as well as it ought to have been within the level design. The levels were all there, but nobody had really spent time placing vapour (used to spur the Jett onwards) or fine-tuning layouts. There were just so many noodley little pieces, and so we needed people to actually come in and track them, inventory them, lay them out, and generally pay attention to them all."

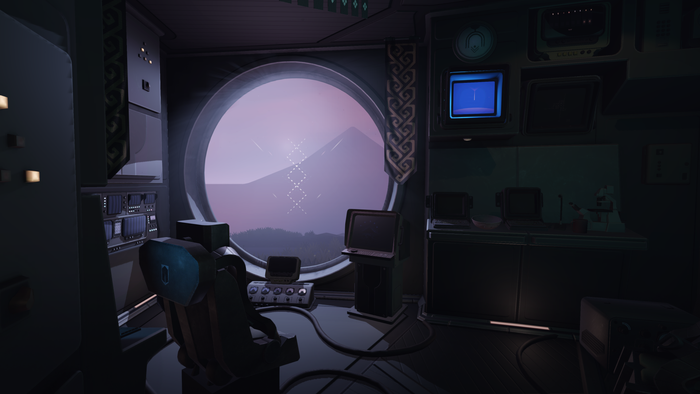

Using the flight model of the Jett itself as a specific example, Adams recalls how the team had to balance a number of different design considerations, creating a vehicle that could become a darting rocket or an intricate investigative tool, to serve the greater whole.

"[The Jett] was our best effort to bring all of these different intense motivations to bear. I think the flight model and controls can be a great strength, and then there are places when they're not so much a strength," comments Adams. "Our ability to smooth off every rough edge was limited, especially with so much design surface area. But the intent was, a bit like in Monster Hunter, where you have to wrap your head around how it's going to work -- but then once you do, you do feel that level of competence and confidence."

As he mentioned earlier, Adams also took design cues from MotorStorm: Pacific Rift -- or as he describes it, "the greatest video game ever made" -- by incorporating an overheating mechanic alongside a surge feature, which demands players take a more measured approach to transit then simply holding down the accelerator. Scramjets, which are a Jett's primary source of propulsion, must also be toggled on and off manually depending on whether a situation calls for high-octane speed or more considered traversal. Shields need monitoring, too, and there special 'pop' and 'roll' manoeuvres that add bounce and zip. That cacophony of controls ultimately results in an experience that can feel unnatural and unruly at times, but eventually makes players (or this one, at least) feel like an intergalactic ace when they begin to click.

"The toggling scramjets is a weird one, and you could simplify the design by not having it, for sure. But it does enable you to have these distinct feeling modes that players can toggle through impactfully, and it's nice to have them be complementary," continues Adams. "The reason we have scramjets on, and stay on, is so that players aren't babysitting the accelerator the entire time, which lets them sit back and use the camera and have a little bit of cruise control."

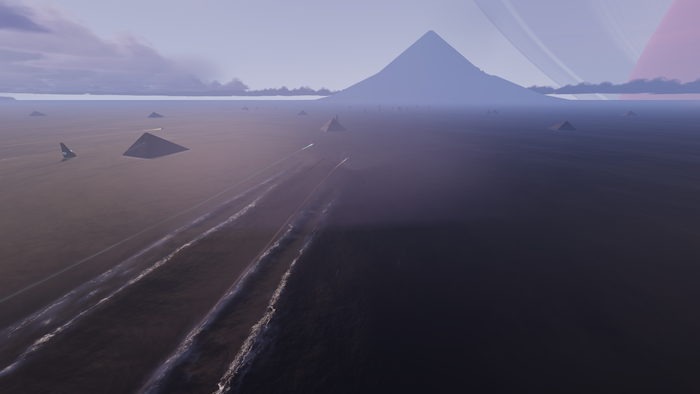

As players use their Jett to explore those hazy far shores, they'll encounter flora and fauna that can be scanned and often repurposed to solve puzzles. Some of those lifeforms are friendly, but there are others with more malevolent motivations that demand evasion or even retaliation. There are also moments where your co-pilot (a fellow scout called Isao) will feed you valuable mission information and exposition, and instances where players will be asked to disembark from their Jett altogether to complete a task on foot. Introspective beats are there to be savoured, too, but amid the relentless hubbub of Jett's ambition Adams laments not giving players more respite.

"[From a design standpoint] we're like 'here's this new idea, here's that new idea.' On some level that's intentional -- like, wouldn't it be cool to frontload with this, this, this and this?! 'Now there's a Colos, and now here's a threat!' But, maybe through a lack of design confidence, we didn't find the places for you to chill. We also didn't figure out why, if you were to chill, Isao wouldn't be checking his watch or pushing you onwards within the context of the narrative. Without that breathing room you plunge headlong [into Jett] and it's a little bit exhausting."

Adams uses the word 'fussiness' to describe Jett's unruly ambitions, and that feels like a fair assessment. The title is constantly stretching players in a bid to deliver the goods on every conceivable front, but when you're creating a game that hopes to blend the best elements of projects like Monster Hunter, Shadow of the Colossus, Motorstorm, and more with what's clearly a unique and decidedly intimate vision -- well, as Adams himself points out, "you'd have to be a genius level designer to get all of that working."

"The fussiness you can feel is because you haven't had a chance to limber up, so when you're faced with challenges it rubs you the wrong way. Once you get to the later stages, it does open out a little bit. You can find your feet and warm up to how it works. There's a feeling that it takes about 10 to 15 hours to fall in love with the positive aspects of how Jett controls -- but then the game is only 10 hours long," continues Adams.

It should be said, those positive aspects aren't as scant as Adam's refreshingly candid assessment might suggest. There's a lot to love about Jett, and when its various systems and themes begin to sing from the same hymn sheet, it's hard to describe the sci-fi title as anything other than a religious experience. Those transcendental moments -- which I don't want to spoil here, but stick with it for an hour or so and you'll see what I mean -- are as much a result of the dev team's herculean ambitions as its shortcomings.

"This whole house of cards was in pursuit of a very tricky, nuanced vision," notes Adams. "The thing we were driving towards was this very niche idea, [...] but I think the dream throughout was to deliver those moments where maybe you're in a scenario, or on the edge of it, and you start to feel something. And even though the story isn't actively happening, you've got so much to think about. That's what we were going after, and so I hope it's the thing that resonates -- because that's what we were fighting for throughout."

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)