Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

What was it about the environment at Lucasfilm Games during the golden age of its graphical adventure games in the 80s and 90s? Why are we still talking about those games today? We polled our development community.

This story is being highlighted as one of Gamasutra's best stories of 2013.

The gutting of LucasArts earlier this week was a tragic loss for the video game industry, but for many of us, it was more than that.

It was more severe of a loss than the cancelled projects, the rumored 150 job losses, or the between-the-lines message that even a company as diverse and global as Disney puts little value in game development.

No, for us, the death of LucasArts was the death of a dream. A dream rose-tinted by nostalgia, perhaps, but a dream nevertheless. A dream that one day, the unique environment that birthed what may have been the most wildly creative studio in mainstream game development history would, somehow, come back.

It was a far-fetched dream, but as long as the name LucasArts continued to exist, a small part of us held onto it.

A lot of innovation came out of the studio, but without a doubt, the strongest legacy it left behind was its series of graphical adventure games from the '80s and '90s. Unique, story-driven, easily-accessible adventures with titles like Grim Fandango, The Secret of Monkey Island, and Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders.

By most accounts the last truly great LucasArts (or Lucasfilm Games, if you go back far enough) game was released almost 15 years ago, and yet, many in the industry still hold these titles as the benchmark not only for comedy writing in games, but for narrative-driven games of all kinds.

But why is that? Why is it that we still consider these games among our pinnacle achievements as an industry? Why do developers still namedrop Monkey Island in pitch meetings when discussing their proposed game's story? Why do we all continue to mentally associate the word "LucasArts" as the splash screen we see before a graphical adventure game, even though the company hadn't released one in over a decade?

We turned to our game development community to find out. Specifically, we asked via Twitter and Facebook:

What is it about the classic LucasArts adventure games that makes them timeless? Why are we still talking about them today?

We've collected a good majority of the answers below. Following these responses, as a special treat, Lucasfilm Games veteran David Fox attempts to answer that question with his own insider perspective.

(Image credits: MobyGames, Lemon64, The Scumm Bar)

Helping Green Tentacle get a recording contract was the least of your worries in Maniac Mansion.

Helping Green Tentacle get a recording contract was the least of your worries in Maniac Mansion.

They often broke the fourth wall and made you feel like you were in on the joke. As if the joke was "Can you believe we get to make these things?"

It was exhilarating and inspiring. Even today, my fantasy of what game development nirvana feels like stems from my experience playing those games, and the insinuation that they were created in the most liberating and creative environment on earth.

- Mike Mika, development director at Other Ocean Interactive

People always talk about how hard it is to make a comedy game, and maybe it's true, but LucasArts made it look easy. I still go back and play Day of the Tentacle every couple years with my wife, and man, that game holds up thanks to its perfect delivery.

From that one game I have learned a lot about how to be funny despite players having control over the timing of a scene, and I learned when you really just have to yank control away from them in order to drive a joke home.

- Dragon Fantasy creator Adam Rippon, of Muteki Corporation

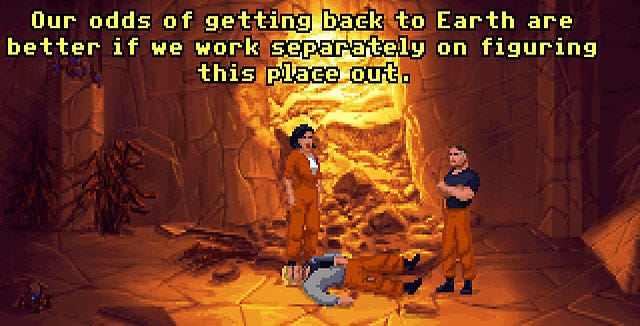

Steven Spielberg himself laid the groundwork for The Dig.

They were that rare combination of original themes and interesting stories mixed with accessible gameplay. In some ways, they are exactly what is hard to greenlight in many modern studios because of the risk of creating new IP on big-budget projects.

They are still relevant because many of today's working creatives grew up in that golden age, so that trailblazing taught us how to be creative, and the nostalgia continues to inspire.

- Game designer Tyler Sigman (HOARD, Sonic Rivals)

What I love about the classic LucasArts adventures as a game industry person is that it seems like every single person in the game industry has played them. So a) you can use any of the games as shorthand when discussing something ("we need like a Manny character for this") and more importantly b) you can instantly learn a lot about someone by what LucasArts adventures they like most.

"Ok, you're a Monkey Island guy? Got it. Still focused on putting the hamster in the microwave in Maniac Mansion? Cool. You like The Dig?! Right on..."

Because everyone has played them, they're basically a Rorschach test for people in the game industry at this point.

- Chris Charla, Microsoft Studios

Day of the Tentacle's unique premise saw players finding creative ways to make objects travel through time.

For every adolescent who turned into a snarky teenager or a sardonic twenty-something, here were games made by our peers. They were games that made sense for where we were in life, made by people who walked the same road as we did.

The games endure because the stories are sharp and respect the audience's intelligence, the humor is inclusive, and because still today when we see "Lucasfilm" or "LucasArts," it brings us back to those childhood memories when all we wanted was a great adventure and friends to share it with.

- Paul Marzagalli, board of advisors, NAVGTR.

Maniac Mansion was one of the first adventure games I ever played, in the early days of Game Informer. It didn't seem to matter that I wasn't an expert gamer... I felt like I got as much out of it as my more veteran peers.

They were expert storytellers, spinning engaging takes with endearing and memorable characters spouting clever dialog. And with each little victory I felt like I was really becoming a gamer and better understanding why so many smart and talented people were dedicated to the hobby.

- Video game PR professional Elizabeth Olson, who cut her teeth on adventure games as the founding editor of Game Informer magazine.

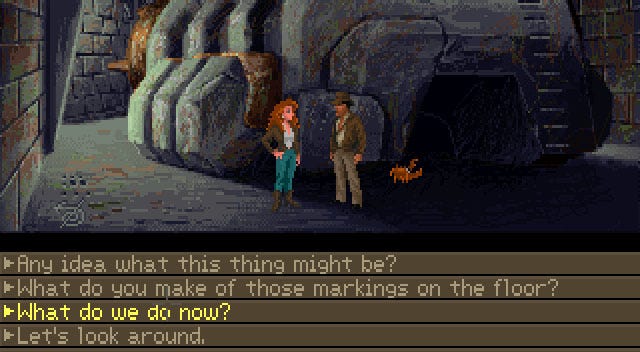

Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis is regarded by fans as a worthy successor to the trilogy of feature films.

LucasArts writers and designers like Ron Gilbert and Tim Schafer brought to the table a wonderful knack for character and dialog, and I think the reason people still talk about those early titles today is that we all have favorite scenes that we still remember.

They also achieved a kind of unstudied greatness that comes from not taking yourself too seriously. Monkey Island II actually ended gameplay with a long list of things you could go out and do other than play video games. Who does that now?

- Game composer Peter McConnell, who contributed music to LucasArts adventures including (but not limited to) Monkey Island II, Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis, Sam & Max Hit the Road, Day of the Tentacle, and Grim Fandango

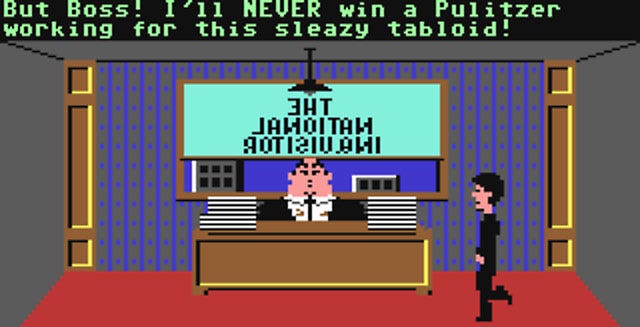

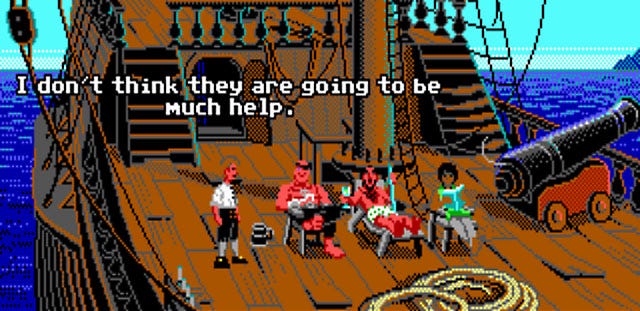

First world problems for our intrepid reporter in Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders.

Monkey Island II was a revelation for me. I could make progress! I could mess up, try again, and eventually get through things! Here was this genre of games that I'd always liked the idea of, but never been able to really enjoy due to difficulty, and someone had finally said, "Hey, how about we ONLY have the fun part." I mean, the beautiful art, the genuinely funny dialog, all of that was wonderful, but the thing I really fell in love with was being able to actually get through the game.

- Ian Adams, game designer at Seattle's Z2Live

They were built on a winning combination of low-stress mechanics and propelled by genuinely good writing.

Many of the characters had heart and soul, the imagined worlds they inhabited were crafted with an impressive attention to detail, and in many cases the personalities and some aspect of the of the creators came through.

Each of the mid-'90s LucasArts adventure videogames is memorable on its own, but taken together they represent a studio's glorious golden age that, in a fate similar to Atlantis (sorry), seemed to suddenly and cataclysmically sink beneath the ocean waves in the late '90s.

- Craig "Superbrothers" Adams

Full Throttle, probably the only game to ever start you off in a dumpster outside of a biker bar.

The Curse of Monkey Island is still one of the funniest games I’ve ever played. Then there was Loom, a beautiful game with a completely unique user interface that used music in a way never used before or since, as far as I know. Finally on my truly memorable scale is Grim Fandango, a 3D evolution from the older SCUMM games -- quirky, funny, mysterious and, once again, unique.

Technology in games is ever improving, but game design, when it’s done impeccably, is timeless.

- Game design consultant and author Rusel DeMaria

Manny Calavera feels a little ripped off in 1998's Grim Fandango.

The worlds still feel original and fresh, and the writing was witty and memorable, where every character is distinct and remarkable.

Even in their time, they managed to cross cultural boundaries. Many people in my generation in Spain, where I'm from, know by heart most of the insults to win at sword fighting in Monkey Island. Many adventure games coming from Europe will include nudges to LucasArts games, from direct quotes to similar puzzles (see Ben There, Dan That, or Ceville). They really struck a chord outside of North America.

- Researcher and scholar Clara Fernandez Vara

Honestly, I don't even know where to begin; they had so many titles that stand out. Their adventures games basically defined an era, with Maniac Mansion, Day of the Tentacle, Escape from Monkey Island, Full Throttle, Grim Fandango.

Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis is probably one of my favorite adventure games of all time. Indiana Jones and the adventure game genre go together... well, like Fedoras and bull whips. And for me Fate of Atlantis delivered not only one my favorite adventure stories but also one of the best Indiana Jones stories ever. Certainly better that the Crystal Skull. Sorry George.

- Infinity Ward executive producer Mark Rubin

You can sucker punch Adolf Hitler in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, but it's not a good idea.

You can sucker punch Adolf Hitler in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, but it's not a good idea.

Maniac Mansion was crafted with seamless perfection. In the same way Mario is timeless and can be enjoyed by any generation, so can the point and click adventure of a group of teens infiltrating a creepy house to rescue their friend.

I enjoyed the storytelling, the clean and appealing aesthetic and after all these years, I can still beatbox Michael's theme!

- Lateef Martin, Miscellaneum Studios

LucasArts adventures are timeless because they introduced an entire generation to the real potential of what a game could do! I remember vividly the excitement anytime I would GET a new adventure game from LucasArts. I’d get so excited I’d READ the manual front-to-back before getting home. I always knew that regardless of the game I purchased, I could PUSH the button toTURN ON the computer where then I’d be invited to GO TO some crazy place.

Perhaps you’d find a NEW KID that needed help? You could GIVE someone a bottle of root beer, READ the National Inquisitor, or PULL up on your motorcycle going full throttle. You could ask WHAT IS the difference between a green and purple tentacle and PICK UP a ticket for the Number Nine. Yes you had to OPEN your mind and USE your brain, but what a wonderfully inspiring and imaginative way to spend years and years and years.

- Chris Campbell, senior producer, studios at Big Fish Games

Bobbin Threadbare's journey in Loom takes him to all kinds of strange places.

It's easy to pick holes in adventure games. Generally speaking, those that came out of LucasArts didn't have any. They were clearly a product of passionate game makers. In addition to their brilliant execution though, their permissive adventures were something that the player could enjoy along with the characters. Not through agency, but through direct experience of their carefully crafted worlds.

Ultimately though, I think their place in our hearts is as much to do with them being brought into our collective consciousness as the first sizeable generation of gamers and game developers were finding their feet. LucasArts adventure games played out alongside us during our formative years and have, as such, stuck with us since.

- Gareth Jenkins, of independent developer 36peas

Sometimes, the words just aren't there for The Secret of Monkey Island's Guybrush Threepwood.

Sometimes, the words just aren't there for The Secret of Monkey Island's Guybrush Threepwood.

These were not games, they were stories and experiences that were unlike anything players had experienced before. The developers had stories and experiences that they need to create, and they were given a chance to do just that.

- Seth Sivak, of independent developer Proletariat

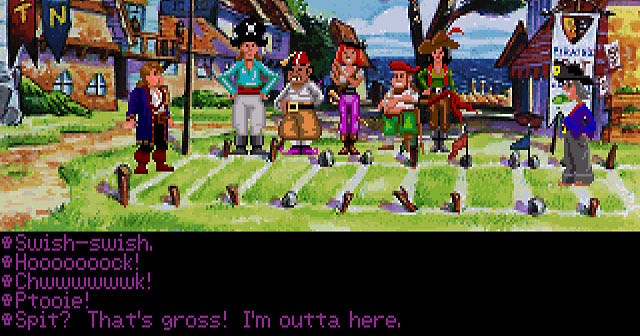

I think all game developers appreciate clever games, and you can always talk to them about their favorite puzzle in Day of the Tentacle (putting the sweater in the dryer for 400 years to shrink it to hamster size for example).

LucasArts adventure games are a rare breed of game you can return to every few years, not remember all the puzzles, and still have a blast trying to solve them again whilst enjoying the wonderfully goofy characters and their dialogue.

- Grand Davies, Endgame Studios

Monkey Island 2's spitting contest puzzle is among the game's most complicated. Watch the wind!

Monkey Island 2's spitting contest puzzle is among the game's most complicated. Watch the wind!

In adventure games, verbs are mechanics and writing is gameplay. The two can live in harmony. LucasArts made some of the best -- by turns thrilling, funny, strangely morbid -- and I will always be grateful for that.

- C.J. Kershner, scriptwriter, Ubisoft Montreal

The dialog is still funny, even today. The gameplay mechanics are dated, the puzzles are hard, and sometimes obscure, but I play them today mostly for the lines of dialog. From trying every action on an object, or every object with every other, to exhausting dialog trees to wring every last drop of humor from the game. It is definitely the writing that stands the test of time.

- Andrew Goulding, of Melbourne-based Brawsome

LucasArts games have always had a special place in my heart; from Loom to Koronis Rift to Ballblazer and the Monkey Island series. Not (just) because they were ground breaking titles for their time but they had that extra special element which fired my own imagination and made me think "what if?" and "wouldn’t it be great if I could do this," elevating a fun game with great mechanics into a world which you wanted to explore and make up your own stories in.

This basic idea is one that I still talk about to BioWare staff. If you can create a world which engages people’s imaginations and fuels and impassions them, they’ll take it to new heights.

- Alistair McNally, BioWare

A tarred and feathered Guybrush terrifies the locals in The Curse of Monkey Island.

A tarred and feathered Guybrush terrifies the locals in The Curse of Monkey Island.

Classic LucasArts adventures are timeless because their influences are timeless. Frankenstein and film noir and buddy comedies and teen movies, classic pulpy sci-fi and swashbuckling movie serials crossed with irreverent, real, believable characters living in outrageous worlds.

I loved Full Throttle's neo-noir before I knew what film noir was. I loved Day of the Tentacle's Bernard, Hoagie, and Laverne archetypes before I'd ever seen the teen movie source material.

But regardless of the specific references and inspirations, classic LucasArts adventures are timeless because great, clever, earnest, memorable, human writing is timeless, and that is the foundation on which all those great games were built.

- Steve Gaynor, of The Fullbright Company

The characters just stuck with me, and catching the in-jokes and cameos between games just made me feel like I was somehow connected, because they were in-jokes that I got.

There were serious moments in the titles, but it's the humor that will always be with me. Like Monty Python sketches, these moments have just wormed their way into my mind and stuck, curled up with an amused smirk, waiting to spring to the forefront of my consciousness even 20 years later.

Basically, LucasArts titles infected my brain.

- Kyle Kulyk, Itzy Interactive

"Hello!" Sam (or was it Max?) makes an entrance that would make Orson Welles proud.

What makes these games timeless for me is the combination of memorable characters and their hilariously witty dialogue. People remember bad writing in games - "All your base are belong to us" and they remember great writing - "That's the second biggest monkey head I've ever seen!" Many games try to achieve great writing by imitating the successes of others, but end up falling flat somewhere in the middle.

- Game designer Jordi Fine

It was thanks to Full Throttle that I began to understand the true power that a great story could have on a game. The Dig, Monkey Island, Grim Fandango... these worlds pulled me in and kept me there. Every detail of the story, worlds, and characters was fully fleshed out beyond anything else I had ever seen in games.

- Dan Silvers, Lantana Games

Guybrush's mutinous crew isn't much help in The Secret of Monkey Island.

To wrap this article up, we asked David Fox -- a Lucasfilm Games alum who was there from the very beginning -- to contribute his thoughts on why the studio's graphical adventures are still held in such high esteem. Here's what he had to say.

When I first started working at Lucasfilm in 1982, we had a heavy burden to bear. How could we create games that were as compelling as the Star Wars films but without mining ideas from the Star Wars universe? While other game companies of the 1980s had to rely on the income from their games to survive, we had the unheard-of luxury of taking our time to get our games right, with years to experiment, try new things, push the envelope, and with no pressure from marketing, focus testing, or even George Lucas. We also had time to develop our company culture, starting where the Lucasfilm culture left off.

So we’d spend months thinking about our games... brainstorming with the other brilliant designers, refining, reworking, revamping, tossing out the parts that didn’t work (or the entire concept) and starting again. One of our edicts was “don’t ship shit” and we wanted to make sure we never did.

Maybe working in a creatively supportive environment like that, one that wasn’t just focused on the bottom line, enabled us to think outside the box, take time to add tons of backstory and detail... tune, tune, and tune again. Until WE felt it was time to ship. Unheard of then and I’m sure even more unusual now (other than with indie games done by people in their spare time).

And yes, we had wonderfully creative people to work with. And that wasn’t an accident. For years, whenever a new designer was about to be hired, they had to run the gauntlet... interviewing with all the other designers. Would they fit in? How collaborative were they? How creative? It was a club where all the members had to vote to let the next one in. We weren’t about to change our culture or quality level, so we all took this responsibly very seriously. And our games showed it.

We never thought about our games lasting for more than a year or two on the shelves. Hardware was changing so fast then. We didn’t consider that people would build emulators and SCUMMVM so they could continue playing them on successively more powerful platforms. I wonder if we had known that if we wouldn't have been much more self-conscious about our designs?

Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders, David Fox's contribution to the graphical adventure genre.

Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders, David Fox's contribution to the graphical adventure genre.

I think one thing that differentiated our graphic adventure games from "the competition" was our goal of creating puzzles that made people laugh with joy when they solved them. We wanted people to have that a-ha! moment when they figured it all out. I think "the competition's" graphic adventures were sometimes mean-spirited, adding barriers to play that sometimes seemed like they were messing with the player.

I know that we learned a lot as we continued to refine the art of creating these games, but you can see elements of the above even with our first ones. We wanted to play with the player, and reward him/her for being outrageously creative in their solutions.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like