What the original Zelda can still teach us about open world design

In Gamasutra's latest feature, veteran designer Mike Stout examines how the original Legend of Zelda created an "illusion of very open level design by u

January 3, 2012

Author: by Staff

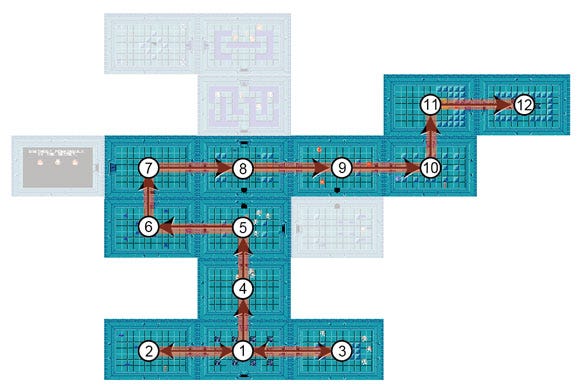

Like many in his profession, veteran game designer Mike Stout (Resistance, Ratchet and Clank) drew much of his inspiration from Shigeru Miyamoto's 1986 classic, The Legend of Zelda. At the time, the game seemed to offer endless possibilities in a sprawling world where anything could happen. In Gamasutra's latest feature, Stout revisits the game from a critical perspective, discovering Miyamoto's masterful tricks for giving players the illusion of freedom in what was, essentially, a fairly linear experience, as touched upon in this brief extract: I always remember getting the feeling that I was navigating my way through the rooms almost randomly, spitting in the designers' faces and getting to the end only because of my mighty gaming talents! After analyzing the flow of the dungeons, I quickly abandoned this notion. As it turns out, the dungeon layouts are very carefully planned and the flow is very cleverly executed. If [co-director Shigeru] Miyamoto's intent was truly to give the players the feelings associated with exploration, then this design is a masterful execution of that intent. The linear layout of the critical path --[the shortest path through a level without using secrets, shortcuts, or cheats] -- was very interesting to me, because when I played the level, it felt much less linear. I often re-traversed rooms I'd seen before. I tried to visit every room, and I tried to collect every item. The levels are also full of shortcuts that cut across the critical path. If the player has bombs, for example, she can skip from Room 5 to Room 8 in the above diagram.  What I found out was that the Zelda development team was able to create the illusion of very open level design by using a few very clever tricks:

What I found out was that the Zelda development team was able to create the illusion of very open level design by using a few very clever tricks:

The critical path is almost entirely linear. This means that it's much easier for the player to find her way through the dungeon without getting hopelessly lost.

Rooms branching off of the critical path make the level feel less linear.

A small bit of room re-traversal at the beginning of the level makes the level feel less linear, but because it only includes a small number of rooms the player probably won't get lost.

Giving small, hidden shortcuts through the level allows the player to feel clever, and allows the designer to disguise the linearity of the level.

In short, the optional paths and shortcuts give the feeling of exploration, but the linear critical path means that as long as the player visits every room in a dungeon she should be able to find his way through. It would seem from analyzing the flow that the level design strikes an excellent balance between giving the player the feeling of exploration and keeping them from getting too lost. The full level design analysis -- in which Mike Stout also examines how the original Legend of Zelda handled intensity ramping, encounter variety, and training -- is live now on Gamasutra.

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)