What Mike Bithell learned in writing his first sequel: Quarantine Circular

"There’s going to be more people doing this kind of thing going forward because it removes some of the technical risk," Bithell says after making first Subsurface, then Quarantine Circular.

“I hate it. I absolutely hate writing,” says writer and designer Mike Bithell. “I find it frustrating, and I don’t like anything I’m doing until the last minute. It does just sound like self-deprecation, but I genuinely find it very stressful.”

Bithell Games' most recent releases, Subsurface Circular and spiritual successor Quarantine Circular, were therefore huge tests.

They’re both narrative-driven games that rely almost solely on the power of Bithell’s words: there’s no voice acting, they take place in one location each, and virtually the only interaction the player has is choosing what to say next in dialogue, which can branch off in various directions.

They’re both ‘Bithell Shorts’, which means they can be completed in a single sitting and cost a mere $6/£4.80. Bithell, whose previous games include Thomas Was Alone and Volume, decided to make Subsurface Circular when a larger project fell through and his team suddenly had six months to spare. Its success, and the reaction of players, prompted them to begin work on Quarantine Circular just two weeks after release, and it was ready just nine months later.

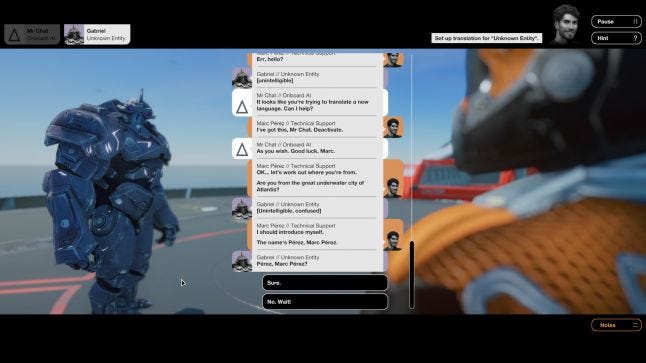

Bithell Games' Quarantine Circular

Bithell says he doesn’t feel like he’s necessarily become a better writer during development—but he’s learned a lot about how to craft a branching narrative with multiple possible scenes and endings. What else has he and his team learned from making these short, sharp games? What were the risks involved with his new approach? And where will he take the model in future?

"What's the biggest amount of money we could afford to lose on me trying this?"

Financially, the games were low-risk. His business partner was initially skeptical about a no-voiceover, narrative driven game, so Bithell asked: “’What’s the biggest amount of money we could afford to lose on me trying this?’ We agreed on that number, and that’s the number we made Subsurface for,” he explains.

"There are lots of indie studios that start from scratch every time they start a game. I think there’s going to be more people doing this kind of thing going forward because it removes some of the technical risk."

But Bithell says both games took lots of risks creatively because his team had never made anything as heavy on narrative. He had “modest ambitions” for Subsurface Circular, and wasn’t sure whether it would sell.

Part-way through development, he was “convinced it was a 6/10”—but feedback from play-testers and others that Bithell trusts suggested that it was much better than that.

When it came out, critics and users gave it rave reviews, and Bithell saw an opportunity. He says he’s not normally a fan of sequels—mostly because “it’s not as much fun as making something completely different”—but players wanted more, and he felt like he had another story to tell using the same techniques that worked in Subsurface Circular.

Looking back, the game’s attempt at branching narrative was “clumsy” at times, he says, with lots of “smoke and mirrors”. He wanted to improve that in the follow-up, as well as create a story that was “more human”.

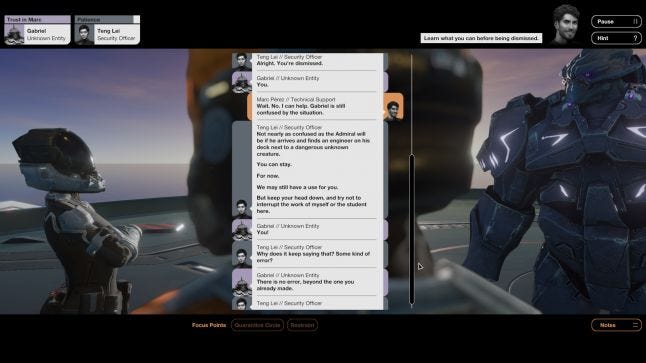

Subsurface Circular, released last August

“Subsurface Circular is all about robots, and it’s cartoony in that—it’s using the fact that they’re robots for jokes and silly contrivances,” he says. “I liked the idea of making something that was more about messy, fallible humans making not-so-great choices, and still trying to tell a coherent story.” He also wanted to try something more ambitious visually, so hired some artists who worked on Mass Effect, and ended up with art that was higher fidelity than anything he’d ever worked with before.

The production benefits of building a sequel

Quarantine was the first time he’d ever made a game without starting from scratch, and working with a lot of the same tools and platforms as Subsurface Circular held huge benefits, Bithell says. It’s given him a “taste” of what AAA studios will often do: take elements of previous games and reuse them in new, inventive ways.

“If Watch Dogs has a cool drone in it, they’re going to put that code in Assassin’s Creed as an eagle. It gave me a taste of that AAA thing, building on a successful structure, which is something I’d never done before,” he says. “There are lots of indie studios that start from scratch every time they start a game. I think there’s going to be more people doing this kind of thing going forward because it removes some of the technical risk.”

He adds that he’d be open to creating more sequels or spiritual successors in the future—or even return to the world of Subsurface Circular for a direct follow-up set in the same universe.

"I think taking away all the game mechanic-y stuff and putting the focus on storytelling…I was surprised and happy that people still liked the story, it stood on its own. It’s encouraging."

Working on quick, intense, low-risk projects also gave Bithell’s team space to shine. Nick Tringali had worked with Bithell on his previous games producing 3D art, but asked to do some coding on Subsurface Circular, and ended up coding some UI elements. He was so good that he became the main coder for Quarantine Circular. “Because things are small and low-risk, individuals can really show what they can do, and Nick’s now doing really exciting stuff on our future games,” Bithell says. “It frees up people to reach for the stars a little bit.”

Bithell is coy on whether he’ll follow the same model again in the future. He’s decided what project the team is working on next, but won’t say whether it’s a larger game or another Bithell Short. “We’ll keep bouncing around different sizes. Bigger stuff, smaller stuff, whatever makes sense,” he says. “We’ve picked one, and we’re making it. It’s off to a good start. I’m already excited, and if you’re excited in pre-production that’s probably a good sign.”

As for his own output, he still hates writing at times—but the reception that both games have received has shown him and his team that their stories strike a chord with players.

“The end product does seem to connect with people. I enjoy that, having that conversation with an audience through a piece of work," he says. “My stuff’s always been very story-driven, but I think taking away all the game mechanic-y stuff and putting the focus on storytelling…I was surprised and happy that people still liked the story, it stood on its own. It’s encouraging."

It means that, whatever he works on next, he’ll still be “bashing my head against the wall until I don’t hate it”—but he’ll be doing it with more confidence than ever.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)