What Makes a Game?

Keith Burgun, founder and designer at 100 Rogues developer Dinofarm Games, argues that some video games are not "games" at all -- and posits a way to home in on the precise elements that make games engaging to players.

[Keith Burgun, founder and designer at 100 Rogues developer Dinofarm Games, argues that some video games are not "games" at all -- and posits a way to home in on the precise elements that make games engaging to players.]

In the beginning, Tetris had a much looser system for random piece (Tetronimo) generation. This meant that when you were playing, you could not be sure of how long it would be until your next line piece would come. This made the decision to "save up for a Tetris, or cash in now" a lot more ambiguous.

Between the new "7-bag" system of piece generation (which puts all seven pieces into a bag and draws them out one at a time, guaranteeing that you will get a line piece every 14 pieces at the latest), the "hold box", and usually five or six "next" boxes, modern Tetris is largely a matter of execution. Maybe you love what Tetris has become, and think that these changes are purely positive. That's fine -- but I think we can all agree that something has been lost.

The Concept of Games

I propose that games are a specific thing.

What I mean by that is that I think there is a unique concept that I can only call "game", and this is something different from the large blanket term we use in the digital game world. We video gamers call everything from digital puzzles, interactive fiction, simulators, to even digital crafting tools "games" (or "video games").

Essentially, anything digital, interactive, and used for amusement gets called a game. And the dictionary will go even further -- it calls a game an "amusement or pastime." So watching TV is a "game." Hell, eating a can of beans can be a "game" if it amuses you!

The thing is -- there exists a special thing, a thing that isn't a toy, isn't a puzzle, and isn't any of those other things I mentioned. It's a thing that's been around since the dawn of history, and it still thrives today. We have no other word for it, really, than "game", so for the purposes of this article, that's the language I'll be using. To refer to the larger category of "all digital interactive entertainment", I'll use the term "video game."

I define this thing -- a game -- as "a system of rules in which agents compete by making ambiguous decisions." Note that "agents" don't necessarily have to both be human, one is often the system (as in a single-player game). But the "ambiguous decisions" part is really crucial, and I am here to argue that it's the single most important aspect in a game.

This is a prescriptive philosophy -- a way to look at games that you may not have before -- not a description of what exists. In other words, of course there are video games (I prefer to adopt the mobile-gaming term "apps") that are puzzles that have elements of games, and there are games that have elements of simulators. I'm here to argue that because of this blurring of the word "game" and its inherent qualities, we are somewhat inadvertently losing this meaningful, ambiguous kind of decision, particularly in the area of single-player digital games.

What Makes a Decision Meaningful?

It's possible that some of us have forgotten how good it is to make an interesting, difficult decision that we can never take back.

Games have a very special kind of decision-making. In a good game, the decisions have the following qualities: they're interesting, they're difficult, and the better answer is ambiguous. Above all else, however, the decisions have to be "meaningful".

I don't mean "meaningful" as in personal meaning, such as "they make you think about your relationship with your dad" (although they certainly could). By "meaningful", I simply mean that your decisions have meaning and repercussions inside the game system; they cause new challenges to emerge, and most importantly of all, they have meaning with regards to the final outcome of the game.

Some may be quick to point out that all video games -- puzzles, simulators, toys -- all involve some form of "decision-making". That is absolutely true, but nothing else forces the player to make decisions in quite the way that a game does. Any decisions you might make in a puzzle, for instance, are either correct or incorrect, and decisions you make in a simulator do not have a larger contest (context) inside which to become meaningful.

A Hierarchy of Interactive Systems

As I said, a lot of different types of media get bunched up together in a giant bracket we refer to as "video games," but as I also said, I think we all know that games are also their own unique thing when it comes to any non-digital fields. Employees at Toys R Us have no problem separating their puzzles from their board games, each of which usually get their own separate areas, for instance.

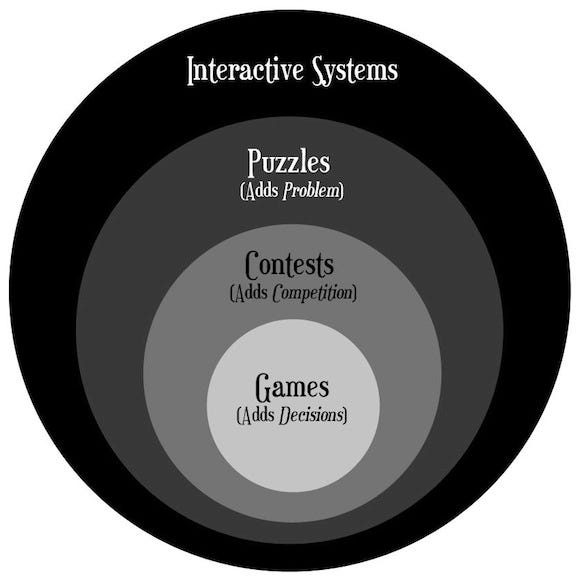

I've created a chart that illustrates the relationships between some of the different types of interactive systems that we encounter in the world casually known as "games":

This image illustrates a proposed hierarchy of interactive systems.

Simulators (Examples: Flight Simulator, Sim City, Dwarf Fortress) -- A simulator is a type of interactive system whose primary responsibility it is to simulate something.

In the end, one of the interesting differences between a simulator and a game is that it's not a valid complaint to say that a simulator isn't fun. Simulators really have no inherent requirement to be fun -- they only need to simulate something.

So, you could have a simulator that simulates something fun and interesting as in Dwarf Fortress, or you could have a plant-growing simulator. It's worth noting that even in Dwarf Fortress, there's no guarantee that anything particularly interesting will happen.

I recall one game where my fortress went totally undisturbed, with almost no significant events happening for many hours. Were it a game, I might be disappointed, but given that it's a simulator, I actually appreciate that this is a real possibility.

To be more precise, the real difference between a simulator and a game is that a simulator is not a type of contest, and a game is. Of course, I suppose you could have a "contest simulator", but the fact remains that competition is not an inherent part of simulation.

Contests (Examples: a weightlifting contest, Guitar Hero, Simon) -- All games are contests, but not all contests are games. The issue is that while contests are competitive, they do not require meaningful decisions. They are often a pure measurement of ability -- a simple question of "how much weight can you lift", or for the example of Guitar Hero or Simon, "how well have you memorized this sequence". It can be a bit hazy in some situations, but generally I think most of us have a pretty good innate sense of what the difference is between a game and a contest.

One exception to this would be something like Guitar Hero, which I expect that many people would be appalled at the thought that it is a contest, and not a game. Firstly, you should know that calling something "not a game" is not a value judgment, although it's often mistaken for one. I personally believe that Guitar Hero is a lot more like a contest than a game, because it is a pure measurement of ability, and I would argue that little or no meaningful decisions can be made during play.

Puzzles (Examples: a Portal level, a jigsaw puzzle, a math problem) -- A puzzle is another word for "a problem". A puzzle has a single correct answer -- a "solution".

Some games can also be solved ("perfect information" games, such as chess, where all the information about the game state is known to the player), however if it is common for people to be able to solve a game, it's considered a knock against that game (Tic-Tac-Toe is solved easily by most people other than very young children, and therefore it is not considered a good game for adults). Puzzles, on the other hand, do not get a knock for having a solution; that's what they're all about.

So do puzzles have "decision-making"? I argue that they do not -- at least, certainly not at all in the same way that games do. Puzzles are not games, because while some puzzles allow players to make decisions, this is actually rather irrelevant to the outcome. All that matters for a puzzle is whether or not the player gave the correct answer.

If a math problem asks four plus six, if you say 10, you have solved that puzzle. What you did along the way changes nothing about the outcome. So, while you can make decisions while attempting to find the solution, these decisions are actually irrelevant to the puzzle. In games, decisions that are made by the player have effects that change the state of the game, and the outcome of the game. So in games, a player's decisions really matter in a way that they don't in puzzles, and this is the way that I draw the line between games and puzzles.

Enemies of the Decision

As I see it, we've got three major issues that are most guilty of threatening the meaningful decision in games. These are also examples of problems which would naturally be avoided if game designers adopted my philosophy for games. They are character growth, saved games, and a story-based structure.

Character Growth. Ideally, a game should be increasing in difficulty as a game progresses. However, we've now got an expectation that our character -- our avatar -- will gradually increase in power as the game progresses.

Of course, designers try to make up for this by cranking the late game difficulty further, but this is a very bad position to put yourself in, and it's one of the reasons why we in video games have such trouble balancing our games.

Essentially, you're trying to hit a moving target. Assuming that the player can become better at the skill of the game, and the character can also become more powerful, and both of these can happen at somewhat irregular rates, the prospect of balancing late-game difficulty becomes impossible.

Anyone who's played a Final Fantasy game through to the end can back me up on this (I remember the final boss of Final Fantasy VII being pathetically easy for my Cloud to take down.) I think the designers of such games are aware of this issue and prefer to err on the side of "too easy".

Of course, if your game is too easy, then your decisions are no longer meaningful (as my decisions weren't meaningful in my Sephiroth battle -- I think it was a foregone conclusion just based on character stats alone).

Saved Games. I call the quicksave/quickload (or any similar system) "the most powerful weapon ever wielded" in a video game. This one is so straightforward that I can keep it short: essentially, a player's job is to try to play his best; to try to make optimal moves. The game allows you to save and load whenever you want. So, when faced with a difficult decision, what is the logical thing to do? Save the game, then make the decision. Well, looks like that was a bad idea! Re-load the game, and try Door Number Two. Hooray! I'm so good at this game!

The issue with saved games is that they insulate us from ever having to make a meaningful decision, a decision that has effects on the game. If you can reload after making a bad choice, then that choice gets no chance to have effects on the game. If you can save the game right before every challenge, then it is no longer a contest. Once again, it's a foregone conclusion. It's only a matter of when you win, not if.

I should mention that there's a common counter-argument to this argument that goes something like, "well, if you don't like to reload the game after messing up, don't do it". The issue with this is that I am having to create extra rules, "house rules", if you will. I am having to do part of the game designer's job, and that isn't fair. Furthermore, many games are actually balanced with this in mind as an element of gameplay, and due to my next item, it's actually rather unavoidable...

Story-Based Structure. Never before video games was there this idea that games get "completed". Instead, games were played in "a match". Now, all games are expected to have a long campaign, capped off by a credits reel. This completion-based mindset has dire effects on our friend, the Meaningful Decision.

Firstly, most story-based games are quite long, with regards to games from throughout history. While most games historically have taken between ten minutes and a couple hours to finish a match, modern video games aren't considered "finished" in any sense of the word for twenty or more hours.

This on its own isn't a problem, but it also means that it becomes a bit cruel and harsh to actually ever give a player a meaningful "loss" condition. So, that means all that they can do is win -- therefore the meaningfulness of their decisions is destroyed. All they can do is beat the game slower or faster; it's no longer a competition.

What, Then, Should We Be Doing?

Again, nobody's having issues with meaningful decisions in multiplayer games -- it's single player games that are proving to be the issue here, so that's what I'll be addressing. Firstly, for any single-player game, you simply have to have random elements.

If your game doesn't have randomness, then it has a correct answer, and if it has a correct answer, then there really aren't meaningful decisions for a player to make (it more closely resembles a puzzle as described above). Further, if you care about having any meaningful decisions, then "losing" has to exist in some form, and having several flavors of winning doesn't count!

Many of you who know about the dungeon-crawling genre known as "roguelikes" might know that they are one of the last defenders of this sort of play in a single-player game. The internet podcast Roguelike Radio recently had a show topic called "Roguelike Features in Other Genres" (listen to this episode here).

I was a guest on this episode, and I predicted that we were going to start seeing more and more quote-unquote "roguelike" features in all genres of single-player games. Not because of how great roguelikes are, but because roguelikes don't actually own concepts like "permadeath" (which really just means, losing) and randomization at all -- up until the 1990s, all games had these qualities.

Here's a few examples of single-player games that do, in my view, have meaningful decisions.

Klondike (the solitaire card game that came with Windows, which we often just refer to as "solitaire") is a solid example of a single-player game that has real meaningful decisions. I've been playing the game a long time myself, and while it might not be clear to some who've only played a handful of games, I notice these moments where I have a real choice that changes the future challenges and even the outcome of the game.

More recently, Derek Yu's Spelunky ran with this concept, literally, and became one of the first well-known platformers to do what I've always thought platformers should be doing: randomizing the levels. Because the levels are random each time you play, becoming good at Spelunky has absolutely nothing to do with memorization or any kind of "process of elimination". It has to do with your skill at making decisions in Spelunky.

Desktop Dungeons is not only a game with meaningful decisions, but it does so in a brilliantly innovative way. In the game, you gain bonus experience for defeating a monster that's higher level than yourself. So, you can choose to use potions early-game (usually reserved for the end-game boss) in order to defeat some mid-level monsters to get that extra experience.

It's a great example of an "ambiguous decision" -- you don't know for certain if the spent potion will be worth the extra experience or not. No level of experience playing other games will have really helped you make this decision, either. This is what's so exciting about games: the idea that when someone comes up with a game that's really new, it actually exercises your brain in new ways. It forces you to make new kinds of decisions that work in a way that your brain never had to work before.

If we can agree that meaningful decisions are important, then we can hone in, focus our games down on offering as many interesting, meaningful decisions as possible per moment spent playing the game. I call this "efficiency in game design".

While Klondike does have some meaningful decisions, it has many no-brainers, or false decisions -- so I'd say it has a rather low level of efficiency in this way. Spelunky's a bit higher, since it's real time and you're actually threatened most of the time, but there are still some situations that are no-brainers. Desktop Dungeons is highly efficient, and while it may seem to newcomers that there are no-brainers, better players realize that the most obvious moves are rarely the best ones.

And here's another way to look at the whole "ambiguous decision" thing -- this is what makes games special and interesting: even when you won, there was always room for you to have won by more, and you're not sure how. In contests, you always know how -- hit the moles even faster when they appear next time. There's no ambiguity about what you should be doing. In puzzles, if it's solved, it's solved. There may be different ways to solve the puzzle, but all solutions are equal. This feeling of "I wonder how I could improve" is what's so magical and amazing about games. In a way, games ask us to rise to our unknown theoretical highest level of ability, and this is really valuable.

I propose this philosophy about games not to be pedantic or controlling about how we look at games. It is my sincere belief that the only way we can really improve our games is by looking closely at what makes a game a game. I don't see many people really doing this; instead I see a lot of people simply echoing safe but conversationally useless ideas like "games are different things to different people".

Again, I propose that we remember that there is a thing called game, and even if you don't agree with my ideas, I hope that you do pursue your own truth about what games are, so that you can focus your games into the most efficient, fun games they can possibly be. To quote the author Robert McKee in his book Story, "We need a rediscovery of the underlying tenets of our art, the guiding principles that liberate talent."

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)