Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In the midst of the collectible card game craze taking over the social space in the success of Cygames' Rage of Bahamut, Will Luton examines the original collectible card game, Magic the Gathering, and the important lessons it has for today's video game designers.

In the midst of the collectible card game craze taking over the social space in the success of Cygames' Rage of Bahamut, Will Luton examines the original collectible card game, Magic the Gathering, and the important lessons it has for today's video game designers.

Magic: The Gathering has undergone a revival lately. The game's current card set, Return to Ravinca, is widely regarded as one of the strongest in its 19-year history, with retailers running low on supplies worldwide.

MTG alone invented and defined the CCG (collectible card game) and its revival -- which coincides with developers racing to build gacha-fusion card battlers in the mold of GREE and DeNA's Japanese hits such as Rage of Bahamut and Doriland -- has made it Hasbro's top IP, as well as the most popular CCG in the U.S.

Richard Garfield designed the game in the early 1990s -- after Wizards of the Coasts rejected his idea for a board game. Although impressed with RoboRally, Wizards wanted something portable and low-setup that could be played in the downtime between other games. Garfield returned with the concept of a CCG, and the game launched under his guidance in August of 1993.

Magic's core concepts are pretty simple: Use land cards to generate mana, use mana to cast spells and summon creatures, then use those to attack and defeat the other player. The complexity, however, comes from the emergent strategy generated by both these base rules and the over ten thousand unique cards that could potentially make up a deck today.

All physical games can inform us, as video game makers, through the insight provided in learning and arbitrating the rules normally hidden by their digital equivalents. However, MTG is able to offer more than most, thanks to its depth in balancing, limited resource control, and variable reinforcement. Alongside what can be gained in design are the lessons in marketing, visual design, and community management.

Magic is a treasure trove of learning, and as a relapsed MTG addict and a designer, I'm going to share with you the top five things we can all gain from its success.

Chess is a classic of game design due to its emergent strategy. The base rules of the game are relatively simple and uninspiring by today's standards, yet the complexity that arises from the movement and counter-movement between two players is beyond what could be mastered in a lifetime.

The human mind can't comprehend the complexity of cause and effect in chess, so it goes about seeking patterns in order to model and understand it. When the mind uses these models to apply a strategy that generates a win condition, it provides a sense of satisfaction and exhilaration as a reward.

Designing for the sort of emergent strategy found in chess is elusive, if not impossible. You are far are more likely instead to discover it in an early form and then build upon it, as is the case with Magic. Indeed, chess itself has evolved to its current form over 1,500 years.

In Magic, players control creatures that have two stats: "power" and "toughness". When in play, their controllers may assign them to attack and, in response, defend against attacks. This simple rule provides a good deal of MTG's core strategy.

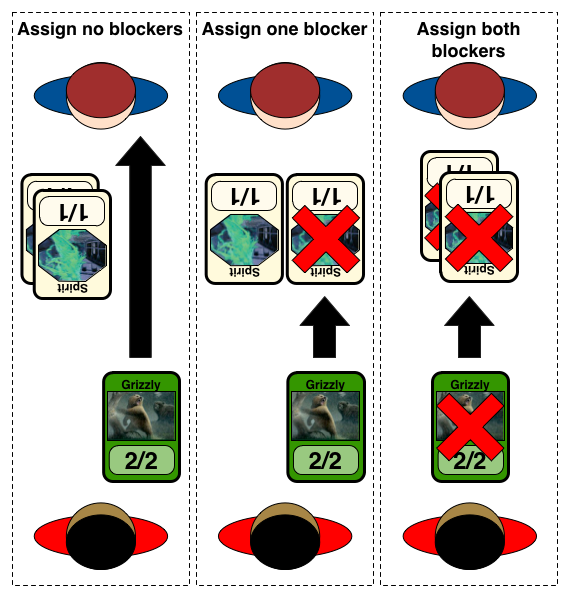

For example: It is player A's turn and they have a "Grizzly Bears" creature on the battlefield, whilst player B has control of two "Spirit" creatures.

Grizzly Bears has a power and a toughness both rated at two (depicted as 2/2), meaning it will deal two damage to a player or any defending creatures, yet will be killed when two damage is inflicted upon it. Meanwhile Spirits have power and toughness each of one (1/1).

Player A declares Grizzly Bears to attack player B. In response player B three options: Do nothing and take the damage from the bear, assign one of the Spirits to defend or assign both Spirits to defend. Below is a matrix of outcomes in each scenario:

Assign no blockers | Assign one blocker | Assign both blockers |

|---|---|---|

Player B loses two life points (10 percent of life total). | One Spirit dies. | Both Spirits and the Grizzly Bears die. |

A player's decision in this situation is likely affected by multiple other factors, including the other cards in play, their hand, their deck, and creature abilities. For example: The Spirits have the ability Flying, so Grizzly Bears (which do not have Flying) cannot block them, meaning they can attack unchecked for two damage next turn.

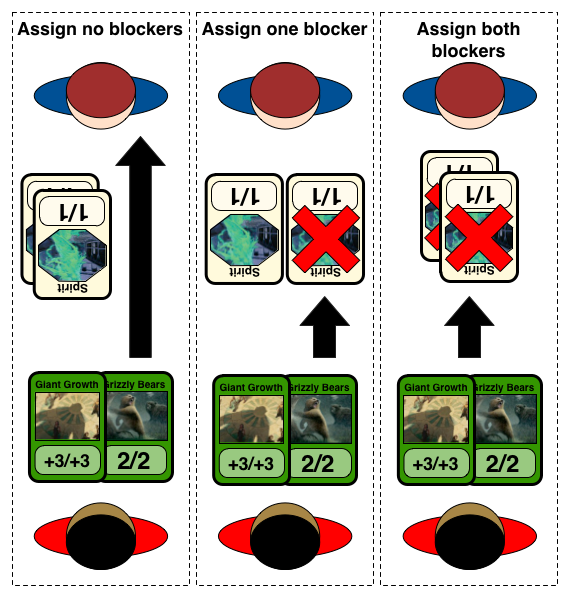

Also in consideration are the remaining mana and cards in each player's hands, due to the potential to play "tricks". For example: Player A has declared attack with Grizzly Bears and has in hand, unbeknownst to Player B, Giant Growth.

Giant Growth is an instant card that can be played after attackers and blockers are declared, bolstering a target creature's power and toughness by three. With Giant Growth applied to Grizzly Bears, it can do five damage and dies after taking five damage. Below is a matrix of outcomes for this new scenario:

Assign none | Assign one Spirit | Assign both Spirits |

|---|---|---|

Player B loses five life points (25 percent of life total). | Spirit dies. | Both Spirits die. Grizzly Bears survives. |

Player B, however, may have a Cancel card, which would counter Giant Growth and so be played accordingly. Possibly, both players expected to come up against each other's abilities, and built their decks around them with many spells or counterspells.

This second-guessing of a player's actions and card selection is known as the metagame -- a big part of all tournament play. The range of abilities attached to creatures, spells, and lands gives any player thousands of options in any game. Each set, of which there are four per year, usually provides one or more new ability to the game; this creates a constantly shifting landscape for players.

As in chess, building mental models and applying them for success triggers the brain to provide a sense of satisfaction. However, unlike chess, MTG's emergent strategy is somewhat forced by the printing of these sets -- building out the options for a player which the community will find, as a hive mind, the best ones.

Players then build, play, and refine decks over the months as sets are released. The strongest prevail, with supply and demand economics making many rare cards (known as "chase rares") valuable. When another player builds a stronger deck or a combination of cards that defeats the strongest decks, the economics shift.

Magic teaches us to design a game which is basic at its core but gives players a multitude of meaningful options in play, even if that is somewhat forced. This provides a game that has a learning curve -- one that will keep players striving as they discover and apply strategy.

Imagine it is your birthday, and all your friends each bring you a wrapped present -- yet you can't open them until you call a coin toss right twice in a row. If you call one wrong, you get another go, and keep going until you win.

Now imagine the same proposition, but instead of presents being wrapped, they are open for you to see -- things like socks, books, and DVDs; some things you want, some things you don't. Which is the most compelling?

In the second example, the coin toss feels like a chore, whereas knowing you're going to get something but not knowing what it is makes the coin toss more (if not very) exciting.

This is called variable reinforcement, and leads to repetition of an action much more consistently than a fixed equivalent.

In MTG each player draws a card from his or her deck each turn. It is possible whole games could be won or lost on a single draw. This gives playing the game an addicting quality in the short term, which marries with the strategy of deck-building, plus the game's goals (see Lesson 3) in the long term. It also provides the game with somewhat-affectionate nickname "Cardboard Crack."

This same theory can also be applied to the addictive nature of sealed packs of 15 semi-random cards known as booster packs. Boosters feature a set ratio between common, uncommon and rare (or mythical rare) cards, plus a land and tip card or token. With each pack you know how many cards you are getting when you buy it, but you don't know which cards you'll get.

The scarcity of each card is actually printed on it, and the ratio of cards in boosters breaks down as follows:

Rarity | Makeup |

|---|---|

Common | 71.4 percent |

Uncommon | 21.4 percent |

Rare | 6.3 percent |

Mythical rare | 0.9 percent |

With 15 mythical rare cards in Return to Ravinca (the latest set), it means if you wanted a Jace, Architect of Thought -- one of the strongest mythical rare cards in the game -- you have a 0.06 percent (or 6 in 10,000) chance on a single card, 1 in 120 per booster, or less than 1 in 3 per booster box (a pack containing 36 booster packs).

With 15 mythical rare cards in Return to Ravinca (the latest set), it means if you wanted a Jace, Architect of Thought -- one of the strongest mythical rare cards in the game -- you have a 0.06 percent (or 6 in 10,000) chance on a single card, 1 in 120 per booster, or less than 1 in 3 per booster box (a pack containing 36 booster packs).

These numbers, anecdotally, stack up very similarly to many gacha-fusion card battlers. Each purchase has the potential to deliver an "epic pull" -- a card that is so powerful it can stack games in the favor of the player -- yet the likelihood is against it happening, encouraging players to repeat the action.

Magic even has it own tournament format that utilizes the compulsion of opening boosters. In booster drafts, players bring three booster packs. Each player opens one at a time, taking a card and passing it on to the next player, who also takes a card and passes it on.

This continues until the pack is depleted; then, the next one is opened, and so on. When all boosters are depleted, each player has a stack of cards with which to build a deck that is used in a tournament.

MTG is possibly one of the best examples of using variable reinforcement in both play and at retail. The probabilities of rarity for each purchase and the thrill of the draw each turn make it an incredibly addicting experience.

Playing Magic will help you to understand the subtleties of variable reinforcement, whilst applying the theory to your own games will likely heighten both player enjoyment and retention, whilst also balancing out skill and chance.

Variable reinforcement is not the only way Magic inspires lifelong dedication and spending from a great many players. It achieves these aims via a series of explicit and derived goals that satisfy and retain a number of different player types.

These mechanics can be applied to offering possible appeasement through play to the four Bartle Types of Achievers, Explorers, Killers, and Socializers.

Explorers: World, Strategy, and Theory

Explorers like discovering and mapping worlds. Whilst the cards of Magic tie in with a narrative based around the "Multiverse", and there are novels and other fiction available, the majority of explorers in MTG enjoy organizing and sharing their discoveries of the game itself.

The web community on Wizards of the Coast's own is host to a great deal of strategy and theory, with videos and articles on deck construction and gameplay techniques. The cards already provide explorers with a lifetime of possible combinations and categorization, but the constant release of new sets expands this indefinitely.

Killers: Tournaments

Killers like the buzz of triumph over an adversary. MTG as a zero-sum (one winner, one loser) game provides this thrill over the kitchen table, yet the popularity of casual and official tournaments put on by DCI, Magic's tournament regulating body, provide much more opportunity for the aggressive Killer.

Wizards boosts the popularity of tournament play by offering cash prizes and prestige to winners of the official Pro Tours, who become celebrities of the game. This legitimatizes the long-term goal of becoming a Pro Tour champion for any dedicated player, driving them to be continually loyal to the game.

Achievers: Planeswalker Points and Collecting

Achievers like clear indications of their progress. Planeswalker Points are a system for players of DCI-sanctioned tournaments provided by Wizards of the Coast. The points tick up for doing ancillary things like joining guilds, but primarily come from playing in tournaments. DCI maintains league tables of local players, which encourages them to continuously engage in competitive play, stay in the Magic fold, and improve their decks through the purchasing of new cards.

Additionally, each set is accompanied by a player guide which lists each card in print on a checklist. This targets a subsection of MTG players who perhaps aren't even players at all: collectors.

Collectors stay focused on the self-appointed goal of completeness and the checklist is a measure of their progress. The human mind instinctively focuses on a scarce resource or deficiency (often money or companionship, but sometime the blank tickbox) and then formulates ways to rectify this lack.

Collecting is a strong goal set in lots of games, from alternate costume unlocks to gamifaction badges. It works either with finite (cards) or infinite (Planeswalker Points) resources.

Socializers: Building a Network of Friends and Teams

Socializers like interacting with people. Whilst Magic dictates that the players need at least one other person to be able to play, committed players will seek out a large roster of potential opponents.

The community around Magic is absurdly strong at local, national, and international levels. Wizards of the Coast's activity starts through local organized play sessions like Friday Night Magic, which are run in conjunction with local retailers (often comic shops) and also through the internet. There are other sites that unsurprisingly offer forums, chat, and articles, as with so many other games, but Wizards as developer-manufacturer provide an unusually large amount of community reinforcement.

Furthermore, competition level players (Killers) rely on teams of people filling various rolls, including collectors (Achievers) and deck builders (Explorers), for their success. This further increases the social element and fosters a community around a game makes it a hub for a player's life.

Players with multiple friends in a game are more likely to stick with it for longer than those that have no social connection, making it an important decision for marketeers and designers. If your game can connect and bring people together to have fun it is likely to have a loyal and active fan base.

Balancing and the control of limited resources are important skills for designers, with small tweaks having massive implications for F2P economies. In Magic, building decks teaches a player these skills through the rapid iteration of taking cards in and out, making them conversant in these skills as players, not designers.

Mana, of which there are five types, is produced by color-specific lands at the rate of one per turn once in play. To put a land out the player may play it from their hand, again at a rate of once per turn. Spell cards, however, may be played from the hand without limit, but only if a player can provide their mana cost.

These restrictions, along with a starting hand of seven and drawing from the deck once per turn, form the basis of Magic's balancing mechanics.

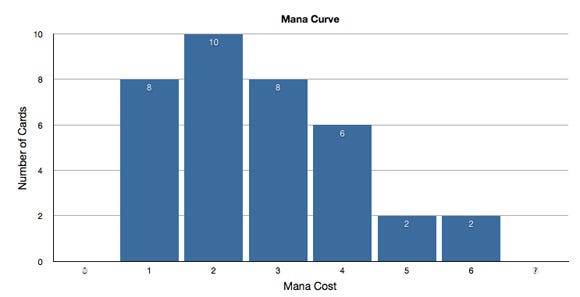

Whilst a deck must consist of at least 60 cards, it may have as many or as few lands as the player chooses, which gives rise to a surprising amount of strategy and consideration.

Too few lands and the player will have great hands full of spells but no land with which to bring them in to play (this is known as being "mana screwed") whilst too many lands means the player is able to play lots of spells but their chances of drawing them is lessened (this is known as being "mana flooded.")

This is further compounded by the effectiveness (or power) of a card being designed to correlate with its mana cost (or how many lands must be used to cast the spell). Low cost cards can be played quickly in the early stages before the opponent is in a position to defend, whilst high cost cards can be played later in the game to dramatic effect.

If the player plays only low mana cost cards in their deck, they will be in a position to play multiple cards in the early stages of the game, but the single draw per turn will throttle their progress as they run out of cards in hand, picking up only low cost, low effectiveness cards that have little impact on the game's outcome.

Therefor the player must consider their mana curve (how many of each card they have at each mana cost) for building an effective deck. If the deck has enough of the most effective cards at each mana cost for the first five turns then it will generally play well, with powerful options always available.

Many sites and smartphone apps exist to help the deck builder analyze his or her mana base and curve, but, whilst helpful, balancing complex systems is near impossible from statistical analysis alone. Small, overlooked elements and subtleties can have massive implications as they begin to interact.

As such, Magic players have devised a method known as "goldfishing", in which they play against an imaginary opponent who does not respond (e.g. a goldfish), counting how many turns it takes to win the game.

From this, and understanding the underlying theories of mana screw, mana flooding, and mana ramps, the player will set about refining by adding and removing cards, adjusting their land-spell ratio and mana ramp for the most effective play.

Goldfishing is very close to the analytics we know in modern video games: the recording of how a system, or more specifically a system under human control, performs. Physically swapping cards in and out takes seconds and drastically effects how a game plays out. This can help a designer plan around the cause and effect in a system too complex to comprehend.

Magic has a second lesson for us here: Pinch points. A pinch point occurs when a resource is so scarce a change in availability has huge knock-on effects to its market price. Chase rares, as described earlier, fuel the economy around Magic. These cards become valuable because of the supply being artificially low, whilst the demand grows thanks to their success in tournament-winning decks.

As booster packs are the only source of these cards, players and resellers open them in the hundreds or thousands, creating huge demand for the packs.

Limited resources define economies; if you are too generous with them, then making money is difficult in F2P. But scarcity's desire-generating effect isn't only applied to IAP economies -- think equipment in an MMO and points in a shmup. Both act as major driving factors for return play.

You may have heard the adage that any good game is still fun with text and box graphics. Whilst true, presentation is a key function of delivering an experience and sets a sense of quality and value in the mind of a player; all great games look great.

Humans are drawn to other human forms, especially eyes. Wizards of the Coast use key cards, specifically Planeswalkers, to showcase human characters that provide players with an emotional reaction. They become emblems across products, both physical and digital.

However, not just Planeswalkers but all cards have strong character imagery. For example, a modern printing of Mind Rot features a striking image of a character praying with the top of his skull collapsed whilst Switcheroo depicts a dragon facing off to a turtle. Both, as with all cards, tell a story of their function.

The artwork of the cards has its own fandom and many collectors take more interest in it than the game itself, with original artwork exchanging hands for vast sums.

Moreover, Magic is an information-rich game and the border color and character artwork makes cards distinctive between each other, and so creates a mental association between the physical object and its function. Watching high-level players play is an incredible experience, especially when considering the sheer number of cards they play against with checking card text.

A flash of the Mind Rot artwork informs an opponent that they must discard two cards whilst the functional placement of a card's mana cost, type and text are laid out to make interpreting them easy for players less familiar.

Furthermore, supporting artwork of card borders and packaging drive the brand of Magic as a whole as well as the characteristics of each set. Clearly care is spent to create a sense of quality that pervades almost all of the modern Magic products: Shiny boosters, foil cards, and nicely fabricated boxes make opening a product an exciting event over and above the random chance of rare cards.

The game would not enjoy its success today had the cards been crudely drawn and printed on flimsy paper. The world it sets and the quality it presents, as with any game product, comes from the physical and the visual.

In video games we've long been good at visual fidelity, but now within F2P we need to pay more mind to how we create a sense of quality that makes making a purchase and playing easy and exciting for the player.

It is common for characters to be uninteresting or IAPs and menus to be drab because we concentrate so hard on the quality of game mechanics, yet presentation can create a sense of quality whilst character artwork tell us stories. Both build a player's emotional response to the game, which increase their likelihood to continue playing and spending.

The success of Japanese gacha-fusion card battlers derives very clearly from the mechanics of Magic as the father of all CCGs. Yet the game can teach all of us lessons beyond the function and design of these games.

Playing it can give young designers the theory to create emergent strategy and ability to problem solve and balance resources to create a fun, optimized experience that ramps correctly.

It also gives us clues for building variable reinforcement through random chance in both play and purchase, whilst using community, collections and tournaments to satisfying Bartle types and keep players in the long term.

Finally all of these can be bolstered by providing a sense of quality via the visual and physical representation of a product to create value in the player's mind.

Magic: the Gathering is a unique game that sits alongside Dungeons & Dragons and Fighting Fantasy in its impact to the world of games and potential lessons for its players. I highly recommend that you got out and buy a couple of decks (any of the Duel Decks are great starting points) and set about understanding it.

It will be the most enjoyable design class you'll ever take.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like