What happened to PlayStation's first indie dev community?

‘Net Yaroze and the community around it was pretty much my whole life at the time,’ says Chris Chadwick, creator of the award winning Blitter Boy. ‘Sad, I know...but it was great!’

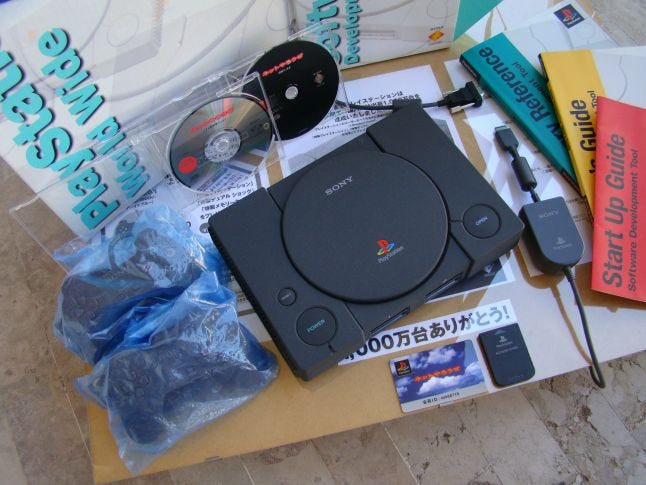

Sleek, black, and mysterious, the Net Yaroze was the shadow-twin of the original PlayStation console. This trimmed-down dev kit allowed neophyte developers to write PlayStation games using tools similar to the ones used by professionals.

The developers on the Net Yaroze were the vanguard of console indie development as we recognize it today. Whilst every platform up till this point had some form of associated homebrew scene, the Net Yaroze marked the dawn of something bigger: a commitment from the world’s largest console developer to foster future talent by way of building a thriving indie scene.

Nowadays, there’s nothing particularly remarkable about a publicly available, consumer-oriented devkit. But in 1997, it was a revelation. The original PlayStation sold over 100 million units, and ushered console gaming into the cultural mainstream. Seven years before the debut of XNA, Yaroze offered indie developers the dream of creating something for that kind of massive global audience.

When the Yaroze was released for $750 USD, a close-knit online community of hobbyists banded together to cut their teeth on console game making. Many of them have since moved on to triple-A development, and some have even founded their own studios. I interviewed several of them recently to get a picture of what this early online dev community looked like.

THE ORIGINAL INDIE CONSOLE DEV COMMUNITY

“There was lots of banter and camaraderie,” says James Shaughnessy, creator of Gravitation. “People would always take the time to help you if you asked how you might go about implementing something, or for help with bugs or with graphics or audio, and give feedback on the games you made.”

"Funnily enough, it was the limitations of the hardware that appealed to me."

“It was all very vibrant and bristling with enthusiasm,” Chris Chadwick, who made the award-winning Blitter Boy, told me. “It really did feel like a close-knit community of like-minded folk, all feeding off each other’s energy and passion for what we were doing.”

Owners of a Yaroze were given access to an exclusive members-only website run by Sony. They were allowed to set up their own individual pages, which people would use either as blogs or simply to share their games (over agonizingly slow modem connections, naturally).

According to Shaughnessy, the private forums “helped to keep the trolls out.” Communication between devs was vital, because the Net Yaroze was no dumbed-down, user-friendly starter kit. Games had to be coded from scratch in C. though the users had access to certain Yaroze-specific libraries. Still, this meant that the sharing of tools and knowledge was pivotal to getting a full game finished.

Chris Chadwick’s Blitter Boy: Operation Monster Mall won the 1998 Game Developer UK Competition

“There was a core of people that committed to the platform and produced some good games and development tools,” says Ben James, developer of Hotline Miami-style top-down shooter Psychon. “However, there were other people that would suddenly appear announcing they'd just got a Net Yaroze and would soon be releasing the next Quake-beater. Most of the time, you'd never hear from them again. Presumably, they quickly realized that game development takes a lot of time and effort.”

“There were a few people on there that would post questions such as, ‘How do I make a game like Gran Turismo?’ We would have a bit of fun with them!” says James Shaughnessy. “There aren’t really any shortcuts. How many people have bought a guitar and given up because they can’t play like Jimi Hendrix within 5 minutes?”

"We were isolated from the Japanese Yaroze community, who were producing some amazing stuff!"

I ask how much Sony themselves had contributed to this successful dynamic.

“Sony did a pretty good job at creating a community for Yaroze members,” says Scott Cartier, developer of Decaying Orbit, who hails from California . “The only part I felt was lacking was how support was divided between Japan, Europe, and the US. Each region had their own member site and forums. It wasn't until well into its life that I found out that the newsgroups for EU Yaroze members were much more active than the US.”

This was a common complaint from the people I interviewed.

“We were pretty much isolated from the Japanese Yaroze community, who were producing some amazing stuff!” says Chris Chadwick.

An example of this work from the Japanese newsgroups was the isometric adventure-RPG Terra Incognita, famed for its technical excellence and hilariously shonky translation. It showcased what the Net Yaroze was capable of in the right pair of hands.

The remarkably polished Terra Incognita was made by Mitsuru Kamiyama, who went on to work for Square Enix

THE LIMITATIONS OF THE SDK

“We were given pretty much all the power of the PlayStation on the Net Yaroze. It wasn’t underclocked or anything like that,” says James Shaughnessy. However, there were still technological hurdles to overcome. A big one was the inability to load files from the CD in real time, like the PlayStation could.

“The main technical limitation was how your entire game had to reside in RAM. While there were methods to stream files from your PC via the serial cable, this was mostly for debug since non-Yaroze members wouldn't have that capability,” says Scott Cartier.

"The serial port seemed to be fond of giving me electric shocks, and blowing up the serial cards in my PC."

Ben James says, “Although the PlayStation had 2MB of memory, the Net Yaroze libraries took up something like 500k of that, so you were left with about 1.5MB to play with. I did run out of RAM once or twice and had to curtail the amount of graphics.”

Developers had to think up crafty solutions to squeeze out what they could from the limited space. Scott, who was working on a physics-based space game, came up with one such solution.

“I was starting to hit some limitations of the Yaroze. Each planet was comprised of several frames rendered out from a simple texture mapped sphere in 3D Studio. I could play tricks with having multiple color look-up tables (CLUTs), allowing for several color variations for each planet.”

This type of innovation was widespread in the community.

“I don’t think the limitations stopped people that much. The creativity was just astounding,” says Scott. He did have one gripe with the system, though: “Debugging on the Yaroze was painfully slow. The unit was connected to your PC via serial cable, and despite running that interface as fast as possible, it took a minute to download and build to the system.”

“Funnily enough, it was actually the limitations of the hardware that appealed to me, in a way!” says Chris Chadwick. “The Yaroze - like all consoles - had a fixed architecture. You had this much RAM, this much processing power, these graphics capabilities, etc. There was no option to fit more memory, upgrade the graphics hardware, or whatever. Consequently, you could be sure that anything you developed would look, sound and perform exactly the same on any other machine. I liked that.

"It meant it was you against the machine (insert "Theme from Rocky"), pushing it to perform as well as you wanted it to. I always enjoyed the satisfaction gained from successful code optimization. I guess this is an aspect of programming that I learned to enjoy, back in my early days. Not that back then I wouldn't have sold a kidney for more RAM and a faster CPU, as standard!”

David Johnston, developer of TimeSlip, expressed a similar sentiment in regard to working with strict memory limitations. “I always quite liked it, because it made you feel like you were really close to the hardware.”

There were a few other ‘quirks’ that were unique to the Yaroze itself, too. “The first problem I had with the system was that the serial port seemed fond of giving me electric shocks and blowing up the serial cards in my PC!” says Ben James.

The Net Yaroze has become something of a collector’s item in recent years, fetching high prices at auction.

The Net Yaroze has become something of a collector’s item in recent years, fetching high prices at auction.

"The high cost of a Yaroze was motivational. No bloody way I was going to spend that kind of money and not end up doing anything with it!"

Another factor that dampened the more widespread adoption of the Net Yaroze was the cost of purchase. Upon release, it was around $750 – a big investment for a learning tool.

“I think the Net Yaroze project's main limitation was the price of entrance,” says Chris Chadwick. “Yes, there were several price reductions (I think it ended up being about half what I paid as an early adopter). Even so, we're still talking about hundreds of pounds.

"I appreciate that Sony won't have made any money from the Net Yaroze program; in fact, they probably made a loss on each unit they sold. I just wonder how many talented individuals missed out simply because they couldn't afford the entrance fee to what must have seemed like some kind of exclusive club, maybe. There were one or two universities running Yaroze development courses, but this still didn’t make it open to all, really.”

He added: “Personally, the cost of getting a Yaroze was somewhat motivational, though. There was no bloody way I was going to spend that kind of money and not end up doing anything with it!”

In the early days of the platform, Net Yaroze owners were only able to share games within the community, as they were only playable on other Net Yarozes – this was quite a bugbear with developers, and more stifling to the community than any technical imposition.

BEFORE THERE WAS STEAM, THERE WERE MAGAZINE DEMO DISCS

“The fact we couldn't burn our efforts to disc came up in discussions on the newsgroups quite often,” says Chris Chadwick.

“Looking at it objectively, now, I guess Sony just couldn't allow this. They couldn't have individuals potentially starting up their own mini Play Station distribution channel, giving away (or even selling) games completely independently from Sony. Sony needed to protect and contain its property and branding, I suppose. To this end, there was a fairly stringent QA process all PlayStation games had to undergo before publication - certain things had to be done a certain way; some things weren't allowed, etc.”

Sony were obviously attempting not to repeat the mistakes that other publishers had made in the past, notably Atari with the VCS. The lack of any kind of vetting of the titles made and released for it allowed a lot of poor-quality stuff to hit the market, effectively ruining the console’s reputation. Some, however, think Sony may have been over-cautious instead.

“The lack of distribution channels was a very real limitation to the Net Yaroze, and is probably what led to its eventual demise” says James Shaughnessy.

Hover Racing was a great but little-known title for the Yaroze

Hover Racing was a great but little-known title for the Yaroze

Later on in the project’s lifecycle, however, Official PlayStation Magazine (OPM) started putting playable copies of these games on their cover discs. They turned out to be a huge hit with players, and a huge boost to the Net Yaroze devs themselves.

“It was like Christmas!” says Scott Cartier. “Finally a way for people outside the Yaroze community to play our games!”

For those selected to appear on the discs, it was a big moment.

"The Net Yaroze and the community was pretty much my whole life. Sad, I know, but it was great!"

“Getting the game on the cover disc felt absolutely fantastic. It really meant something, it was a real achievement as it had to be selected to get on there. To know thousands of people are going to play your little game and might actually enjoy it is why we make games. I heard that they make a million of those cover discs so that was quite special,” says James Shaughnessy.

“It felt great!” says David Johnston. “I knew the print run for OPM was massive and it was weird to think of that many copies of my game being out there.”

It seems strange to imagine now, but it being the early days of the Internet meant it was nigh-impossible for the devs to get any feedback on their games. Some of them had no idea of how well they were received until years later.

“Social media like Twitter and Facebook wasn't around back then, so I didn't really hear much about how people got on with the game,” says David Johnston.

Ben James says this about his first Yaroze game, Psychon: “Well, the journos didn't seem to like it, and it would be years before I'd get any further feedback. About a decade later, folk started getting in touch about it, play-throughs appeared on YouTube and such, one guy was even going to port it to the PC. It seems there's a small band of gamers that really like that game.”

With many of the developers I spoke to now working full-time in the games industry, I was struck by how fondly they all reflected on their early days with the Net Yaroze.

Scott Cartier says “I made several lasting friendships through the Yaroze program. I have even met a couple UK members when I've taken trips to Britain or when they've traveled here for GDC.”

“The Net Yaroze and the community was pretty much my whole life at the time," says Chris Chadwick. "Sad, I know, but it was great!”

****

Dan Chamberlain is a freelance writer hailing from the English countryside. You can read his blog and subscribe to his Twitch channel over at www.superinternetfriends.com

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)