What does HBO's Westworld have to teach us about game design?

Gamasutra staffers discuss the ways that HBO's new show seems to present characters grappling with issues of open world game design and NPC character creation.

October 19, 2016

Spoilers for Westworld ahead.

Earlier this month, HBO premiered its new sci-fi show Westworld. The premise is that in a utopian/dystopian future, a powerful mogul has bought up Monument Valley (or somehow constructed a perfect recreation of it) and built a full simulation of a Wild Wild West setting on it, where guests can pay money to live out their cowboy fantasies, be they innocent or lurid.

Developers and critics immediately took to Twitter to pontificate about how familiar and game-like it seemed. We didn't want to let them hog all of the fun. So Gamasutra staffers weighed in with our own takes on the show.

Chris Baker (@chrisbaker1337), assignment editor: Okay, so many have noted the many different ways that this show is like a game. Customers are deposited in a theme park surrounded by sophisticated robot NPCs, who are designed to cater to the needs and desires of guests, tell them about missions and challenges that await them in the park, etc. Guests can choose to be white hat or black hat, to round up criminals or commit vile acts themselves. The robots can be damaged or killed, but the guests cannot. "Dead" robots are repaired, their memories are wiped, and they return to action. But as the show goes on, we see that there are some bugs in their programming. Not all of their memories are wiped. They malfunction, or become stuck in behavioral loops. They violate their programming.

What game designers may find even more interesting is the stuff that's happening behind the scenes. We see the day-to-day work of the people who design the park and the robots. We see them bicker about the guest experience, we see them propose new missions, we see them try to chase down and solve flaws in the programming of the robots. The show is clearly trying to get at bigthink questions about the nature of reality and consciousness, but from moment to moment, the people running the park seem to be grappling with the issues of game design.

What do we think?

Bryant Francis (@RBryant2012), contributing editor: During the pilot, we meet a programmer, the mogul, the producer, and the lead designer, who all grapple with some of the robots starting to get out of hand thanks to a buggy upgrade. Since it’s a real-world sim and not a game, patching that bug isn’t easy, and leads to the “developers” finding an excuse to recall lots of robots by staging a massacre in town. The robot leading the massacre prepares pauses at one point to give a speech, which someon clearly spent a lot of time writing for him, but is promptly interrupted by an idiot guest. (I think that the narrative designer of Westworld groaning about how a player ruined the experience he was trying to create probably got a lot of devs chuckling with familiarity.) Obviously because this is a TV show, this is only the beginning of things going wrong.

I have a few personal thoughts about how the show mimics the creation of simulated spaces.

Westworld has an interesting thing going in that since you know many of the deaths don’t count, some of its shootouts give an emotionally ‘fake’ resonance. Like, you can’t care about deaths if you know they’ll literally reset the next day. Interestingly, I don’t think this is something I feel in games at all, as I tend to be pretty invested in the fictional gunfight. But the show’s able to use it to create other tensions about these characters and designing the spaces where these fights happen. It’s hypnotic to watch, even if it doesn’t make me reflect on game design that much.

There’s a line one character says that stuck with me about how developers make open world games to supposedly fulfill “true freedom,” even though that’s often a lie. She’s talking about the interconnected narratives, and how they’re meant to be interrupted, but mostly players interrupt them by “killing or fucking” someone. And minus the fucking part that’s really how we design freedom in these games isn’t it? We say ‘oh hey you can interrupt the basic idle flow of the world just by opening fire, then we’ll drop consequences on you.” Some games, like Assassin’s Creed, put huge limits on this but if the creators are going to reference Red Dead Redemption that’s really what Red Dead Redemption does.

Ed Harris’ black hat character is certainly a THING TO TALK ABOUT, since he’s doing this weird metagaming thing where he knows all the scripted interactions and takes pleasure in pulling them apart. Forcing the “NPC” to try and kill him was a really cool bit, and the way the character was horrified by the way bullets bounced of Harris was a nice humanizing touch to what running this kind of world means. I think we’ll be talking him a lot as the show goes on.

So what do you all think? Kris I know you’re eager to quote the robot quoting Shakespeare. :p

Kris Graft (@krisgraft), editor-in-chief:

Alex Wawro (@awawro), news editor: We're only a couple of episodes in, so I'm a little hesitant to throw down on a lot of these points. I do think it's interesting to watch how Westworld seems to celebrate the "lone genius" trope (see: Anthony Hopkins playing the creative director) while also setting up a self-important "narrative director" type (played by Simon Quarterman) and then mercilessly cutting him down.

The show reflects game development in a lot of intriguing ways, but I particularly appreciate the dynamic between the Hopkins and Quarterman characters because it mirrors the often-tense relationship between authored and dynamic narratives in game design. At one point in the second episode, Quarterman's character calls the Westworld leads into a meeting to show them the new storyline (think: video game quest) he's written, hyping it up as a grand adventure that will let players see themselves the way they wish to be. Hopkins eventually ambles in and tells Quarterman it's a waste, and the only thing it shows anyone is what Quarterman wants to be; that in the end, every player comes to Westworld for something different, something only they can understand.

The narrative director unveils his new mission path

The narrative director unveils his new mission path

Is it a stretch, then, to watch this exchange and see reflected in it that constant struggle in game development between telling the player a story, and letting the player tell their own story? Is it a reminder that when we play games, we're learning just as much (if not more) about the people who make them as we are about the games themselves?

Is it just a pretty good HBO show with some really ridiculous set designs?

Chris Baker: Alex, I can see how this show could easily go off the rails after a couple of seasons and become a convoluted mess that makes you question why you ever found it fascinating. [coughLOSTcough] But right now, I... really do find it fascinating.

The acting is amazing. Especially those moments when the hosts instantly transition from being human beings--often terrified, confused, traumatized human beings--into being malfunctioning cyborgs.

I thought that the use of literal bugs to symbolize technological bugs was a little on the nose, but it paid off spectacularly at the end of the first episode.

I love to read all of the pieces out there about interesting game-y elements of the show, the way it riffs on greifers and emergence and scripted NPC behaviors and metagames. But I also want to note that in the past, many people have noted that theme park design has a lot in common with MMO design and open world games. Danny Hillis, a former toy and game designer who was also an Imagineer, has talked about how Disneyland is a big space that presents attendees with clear lines of sight to multiple objectives, and features an array of characters roaming around doing random encounters, etc. [ALSO: Check out Scott Rogers' GDC talk "Everything I Learned About Level Design I Learned from Disneyland," and Don Carson's Gamasutra articles on lessons in environmental storytelling that devs can take from theme parks.]

New arrivals in Westworld literally choose to go white hat or black hat before embarking on their adventures

New arrivals in Westworld literally choose to go white hat or black hat before embarking on their adventures

I'm particularly interested in seeing what the show does with the ability to choose a white hat or a black hat path in the park. Game designers who give players binary good/evil choices often struggle with creating a satisfying arc for the people who choose evil. (Joseph Campbell wrote about a Hero's Journey, but the Villain's Journey isn't as clearly delineated.)

So far, we've seen the black hats pursuing simple acts of sadism and psychopathy in a manner more reminiscent of torture porn horror flicks than Fable or Infamous--if these Westworld characters are pursuing deeper goals, racking up money or XP or territory through their violence, we haven't seen how that works yet.

Only one character seems to be pursuing more long term goals via the black hat path. That's fascinating, but it's very uncomfortable to watch it unfold. People interpret this character as a griefer, but in the context of a TV show, with victims that are portrayed by humans, it just doesn't feel like trolling or "boundary testing."

Like a great game, the show is doing a really admirable job of gradually introducing you to its world. Remember that the Game of Thrones pilot had to be almost entirely reshot because the initial version had huge tedious chunks of exposition, and despite that the test viewers were still unclear on the relationships between the characters. Westworld is setting up the rules and conflicts within and around this weird and unusual futuristic theme park in a way that's never boring or overly expository, and it's also employing some really clever misdirection.

Finding deeper layers of the game in unexpected places

Finding deeper layers of the game in unexpected places

How do y'all think the show reads to people who don't know or care about games?

Phill Cameron (@phillcameron), UK editor: I think when you attempt to put the Westworld experience into a game analogue, then MMOs are actually fairly apposite to what is being presented here, because what we're seeing is more of the ideal of what we want MMOs to be than actually any MMO that has been made (with the exception of perhaps EVE Online). What I mean by that is that Westworld is, by its very nature, exclusionary; if one Guest chooses a path, then it's fairly likely that that path becomes unavailable to any other Guest, because the Hosts involved are either removed or monopolized by the Guest who interacts with them. While things are seemingly reset after a specific period (seems to be about once every 4 weeks), you then have a new batch of Guests coming in to interact with the Hosts.

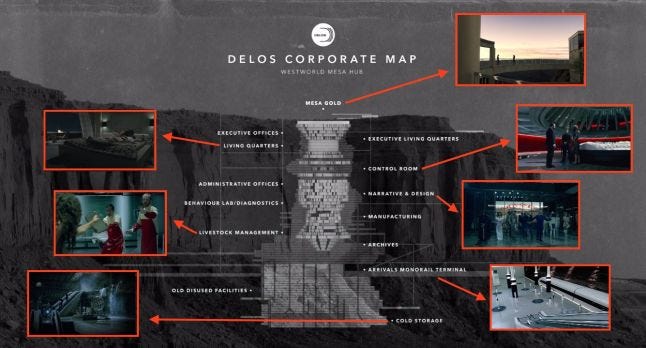

A map of the Mesa corporate facility

The interesting thing here, and what we're not really experiencing as an audience, is that you actually do have, from a player's perspective, impact to your actions. If you kill a Host, or you do something to it in whatever way, it would appear that the Host remembers or reacts to that until it is reset next cycle. In that way you have an experience that is very much taking into account the impact of your decisions and actions, in a way that you can either engage with or ignore, depending on how you, as a Guest, want to interact with the simulation.

I know you've said that we haven't seen much in the way of the 'Black Hat' path, Chris, but I think the fundamental difference here is the approach taken by the characters who built Westworld is one intended to be interacted with, and potentially broken. The more we see, and perhaps most clearly in episode 3, is that there isn't some overarching pre-determined set of events that happens every time. Instead the Hosts seem designed with 'possibility spaces' in mind, where they have their own storylines, but the way that they interact and entangle with the storylines of other Hosts, and obviously the Guests themselves, are potentially unique each cycle. In that way, if a Guest decides to opt for the 'Black Hat' path, they can see and feel the consequences of their actions, and the way it impacts the immediate Hosts around them, in a way that doesn't 'break' the game in a way it might in how we see video games today.

Perhaps the closest example I can think of here is actually Space Station 13, which is built fairly similarly to Westworld, except instead of NPCs it is populated exclusively with people. However it follows a lot of the same tenets that we're seeing in Westworld; everyone has a job, which has a fairly specific set of expectations and functions, and roleplaying is heavily encouraged, if not outright enforced. Each 'round' runs for a few hours, and there are players who have more mundane tasks and others who are deliberately intended to disrupt and subvert what everyone else is doing. The enjoyment comes from the fact that, even if you are a janitor or a quartermaster or something not inherently exciting, as the round progresses things are going to spiral out dramatically, and those ripples will affect your experience.

It makes me very interested to see the end of one of Westworld's 'cycles', as the storylines near their ends, and more and more hosts are removed from play. I would imagine the park is very different from what we've been seeing from the beginning of William and Logan's trip.

Bryant Francis: Some episode 3 reactions: We’ve now seen sort of how the park developers interpret what the hosts should “be” at a conceptual level, and how that grinds up against the various developers working on the project. The Park Director admonishes one employee for covering up a naked host during maintenance, we’ve seen that the woman working in programming has an empathy for them, and we learn of a mysterious co-founder who went too far chasing the idea that these hosts should be conscious, not interactive.

That’s a familiar struggle for AI developers, and one I think Kris wrote about a few months back---the characters in WestWorld briefly note these AI long ago passed the Turing test, which speaks to the casual sci-fi-ness of the show that that can just be a throwaway line. I imagine Kris’s AI interviewees would lose their minds at the opportunity to work with AI who could be perfectly moldable but still not “conscious.”

Because Westworld is a DRAMA we’re now learning about the way these different “game developer” employees react to and feel about their work, and how some of them are more attached then others, or maybe too much. I wonder if game developers feel similarly about their far-more-fictional work sometimes---how it can supplement real-world interactions, help them satisfy certain desires just by working on it externally, etc. etc. And I wonder who’d want to work for Anthony Hopkins.

Kris Graft: To chime in on Chris’ question about how people who aren’t particularly into video games might receive the themes of Westworld—I think they can appreciate the themes, sure. Even though to people (like us) who are familiar with video games see all these parallels with game play and game design and development, the broader themes are still digestible for non-video game types.

Particularly the power fantasy aspect of the game, and the implied question, ‘what would you do if you could act on your basest desires with impunity?’ It’s an uncomfortable question when you’ve been following an industry whose products are quite often about making an entire virtual universe pander to the desires of players (myself included). The part near the end of episode one where the “newcomer” shoots the robber at point-blank range, then laughs and acts giddy at the violence and destruction he just wrought, is particularly unsettling because that’s how a lot of us are when we play video games. Pull off a skillful headshot, execute a fatality, and you get this rush of dopamine to the brain because you just “won” in a competitive scenario, or at least had a meaningful impact on the virtual world around you. I’m not saying playing Call of Duty makes you a murderer, but I wonder, as sensory feedback in games becomes increasingly more capable of realism, when does sadism give way to empathy?

So yeah, Westworld is uncomfortable because (among other reasons) it represents the logical ends to the unimpeded, delightful violence that a lot of video games put at the center of their interactivity. That is, it’s not hard to imagine that if power fantasy and obsession with realism were to continue on the current trajectory, Westworld, in all its tactile hedonism, is representative of the ultimate open world interactive video game.

DANG THIS SHOW IS DEEP, PEOPLE.

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)