Unbound: An Ode to Wired Women

What do the classic RTS Homeworld and the modern mobile game 80 Days have in common? Fascinating female characters who develop a unique relationship with their means of transportation.

“The greatest of these [sacrifices] was made by the scientist Karan S’Jet, who had herself permanently integrated into the colony ship as its living core. She is now Fleet Command.”

~From the introduction of Homeworld (1999)

It’s become a trope of RTS games to have a disembodied voice, usually female, act as the narrator of the game’s minutiae: “construction complete,” “our base is under attack,” et cetera. Command & Conquer, one of the archetypes of the genre, experimented with giving this voice some distinguishing traits in games like Tiberian Sun, but it remained just that: a dead voice.

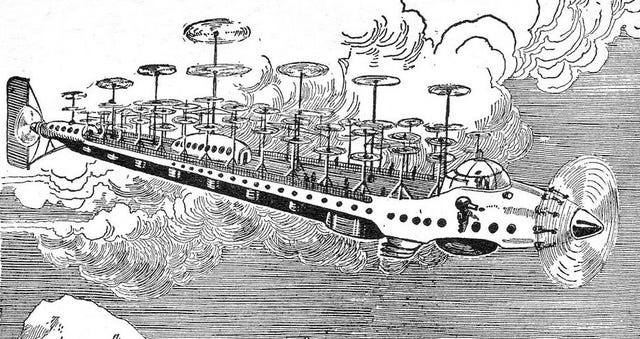

Relic Games’ 1999 Homeworld, which was just recently remastered and re-released for contemporary computers, went in a completely different direction. In that game, which was a landmark for making the RTS three dimensional, that voice belonged to Fleet Command of the Mothership, a titanic colony-cum-factory ship so vast that its computer intelligence required an actual person wired into it in order to process its nearly infinite number of tasks.

Her name was Karan S’Jet.

****

S’Jet was a neuroscientist and a leading researcher on the project that produced the mothership and the wider colonization project--a multi-generational effort by her people to discover their true homeworld and return to it. She volunteered to become Fleet Command in both Homeworld and its official sequel Homeworld 2; “it is neither duty nor obligation that drives me; it is simply what must be,” she said in that second game.

S’Jet was a neuroscientist and a leading researcher on the project that produced the mothership and the wider colonization project--a multi-generational effort by her people to discover their true homeworld and return to it. She volunteered to become Fleet Command in both Homeworld and its official sequel Homeworld 2; “it is neither duty nor obligation that drives me; it is simply what must be,” she said in that second game.

Why bring her up now? Well, in addition to the game’s re-release, and the fact that S’Jet is an incredible example of how to anchor an RTS in a genuinely compelling story (it’s not a coincidence that she is generally considered the “protagonist” of each game, collectivizing the embodiment of her people’s experience in a dramatic way), I was reminded of her by a fascinating character in Inkle’s incredible 80 Days.

80 Days is an interactive fiction game with strong RPG and resource management elements that sees you take on the role of Passepartout, valet to gambling man and wax-mustachioed international cipher of mystery Phileas Fogg, on his famous trip around the Victorian world in 80 days or fewer. The game takes many cues from Jules Verne’s original but also adapts his envelope-pushing storytelling for the 21st century by presenting a fictionalized steampunk 1872, one where the British Empire is not the only game in town and where women, non-white people, and queer folk have significant parts to play in the myriad of stories that can unfold on your journey.

The writing by Meg Jayanth claims many quiet triumphs, but one of its greatest is using the game to explore the meaning of travel to a diverse array of characters, and in the process redeeming it from the tedious slog many people perceive it to be these days. Airships, boats, and trains are not just means of conveyance; they carry the hopes of their crews. Some airships are surrogate children, others are the family home, others are a way of escaping domestic oppression, gender roles, or a parent’s depredations. In the process, as fun as Passepartout and Fogg’s wager driven journey is, your humble valet may find himself in reverential awe of the vast world of experience that travels with them on all those planes, trains, and automobiles. For so many people around the world, the ability to fly or ride on a steamer or drive a Bozek car is not motivated by a staggeringly privileged wager, but by something more primal: the need to live.

"Travel means something different for those who labor under societal disadvantages. It offers a particular, if precarious, kind of freedom. "

One of the most fascinating cases of this can be found aboard an airship between Antananarivo and Rangoon. The ship, the Maminirina, designed by the Queen of Madagascar herself, a confident and bullish technologist, seems to be missing its captain, and the fastidious Passepartout can go in search of her to please his master, who feels slighted by the lack of a personal greeting from the ship’s ranking officer. What he finds instantly brought me back to a childhood memory of Homeworld.

“I followed with some interest all the way to the engine room, where I found a most terrible sight. A woman with dark hair hung suspended amidst the pistons and gears of the engine's heart. Her body was pierced and wrapped with wires; her fingers lay carefully placed between gear-teeth. ... Dead? No. She opened her eyes, which were sheened with a strange white light, and said, "Hello, Passepartout." Her voice was full of oil-smoke and iron. "I hear you have been looking for me."”

Captain Maminirina is the Maminirina.

Unlike with Fleet Command/Karan S’Jet, we get to talk to her, plumb her motivations and actually see the world through her eyes.

She immediately resists being portrayed as a victim of her queen’s technological passions:

"I can feel every living body on my ship. I can feel their footfalls like little tickles, and the sun warming the timber of my hull like a warm bath. "

““Who did this to you?" I swallowed, trying not to watch the lights dancing along the wires that connected her spine to the engine.

"My Queen and her ally, Emperor Cetshwayo, made me," the captain said proudly. "I volunteered to be the first. I am the first, the first," her voice echoed like the sound of pistons.“

There can be no doubt she wanted this, and you quickly learn why. The airship has become her body, her old corporeal form now merely the heart and mind of something much more vast, and unlike Karan S’Jet she cannot free herself. Unlike Karan S’Jet she would never want to. "I can feel every living body on my ship. I can feel their footfalls like little tickles, and the sun warming the timber of my hull like a warm bath. I can taste the air pressure like wine and the steam boiler powering my body like a white-hot heart. My sails touch the sky like a lover's caress… Oh Passepartout, I am so powerful. So beautiful. You could never understand."

There is an old Aeschylus quote, "Bronze [is] the mirror of the form; the wine of the mind" whose meaning is clarified in the penumbra of Maminirina's experience, one where raw minerals enflame and intoxicate your very veins. That is travel, fully embraced.

Passepartout can respond any number of ways, from kissing her at her invitation and experiencing a brief glimpse of Captain Maminirina’s universe, to running away in fear. But what is clear is that what first seems like a hellish trap is, for this captain, the ultimate kind of freedom.

Along the intergalactic path of the Mothership’s journey in Homeworld, you come across a strange seafaring people known as the Bentusi; peaceful cosmic traders who give advice and spread the word of the “Exiles” and your prophesied return. They admire your fleet because of Fleet Command, first and foremost. She is like them, “Unbound,” a formerly organic individual now become a starship.

“Unbound” is a beautifully paradoxical term; your body is bound quite literally but in exchange you find your horizons stretch to the bounds of the known universe. For Captain Maminirina, those are the skies where airships roam; there can be no doubt that she is free.

****

“When once you have tasted flight, you will forever walk the Earth with your eyes turned skyward, for there you have been, and there you will always long to return.”

~Unknown, often misattributed to Leonardo Da Vinci

My Passepartout always goes for the kiss; it’s hard to imagine him resisting the urge to know what Maminirina’s life is like, what it would be like to be unbound.

Throughout the game, the classism Passepartout struggles with is readily apparent and haunts his steps across the world. Though he is, as he so often says “his gentleman’s gentleman,” he is still regarded as a servant by many. Like the women of this world, he has something to escape from through travel, the grubby limitations that fetter him because of circumstances beyond his control (it gives me no end of pleasure that there are storylines in the game that can end with Passepartout ditching Fogg).

Travel means something different for those who labor under societal disadvantages, it offers a particular, if precarious kind of freedom. I grew up in a poor Bronx neighborhood, a Puerto Rican kid whose parents never went to college; for years my world was a few square miles of a New York City borough, and as I got older and transitioned, I quickly learned that being out of doors remains dangerous and uniquely risky for women, whether cis or trans. I can never fully escape from that, but when I travel it feels like the motion keeps me alive and sustains me for that much longer, even if there is every possibility that each flight could be my last. It’s my way of rising above a world of catcalls and being literally spat upon, unbinding myself bit by bit in a process I will never finish, but whose journey is the most satisfying I shall ever take.

It’s why I saw something of my own longings in both S’Jet and Maminirina, and why they may be some of the most interesting female characters yet produced by videogames. What does it say when the ultimate form of freedom for us is the shedding of our bodies?

S’Jet’s unbinding was a sacrifice she made; she did not wish to ask anyone else to undertake the risky procedure she had designed to power the Mothership’s computer systems. And yet, throughout both games there is a sense of willing purpose underlying her integration with the ship’s core. It became an inextricable part of who she was, essential to her becoming a leader among her people and, eventually, something akin to a goddess.

When I fly, I think of her.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like