Together Alone: 'Pure untainted survival' in Near Death

In Orthogonal Games’ Near Death, a “game about survival” centering on a pilot who crash lands near an abandoned polar research station, the main enemy--indeed, the only enemy--is Antarctica itself.

Just what is the “game world”? The setting, surely. The place where players will bounce about in a virtual wonderland. But can it do more than merely provide a place for the action? What if it were the action? Or even a character in its own right? Truth be told, games rise and fall on this proposition. BioWare’s Dragon Age II was significantly hurt by dwelling so deeply in a single city it failed to give enough life to. The city-state of Kirkwall, a place where your character is meant to grow over the course of a decade, never quite materialized, instead feeling like a 3D background. Settings can be (and often need to be) so much more.

Solitude has emerged as a theme in recent indie games, as much because of small budgets as artistic vision. It’s just easier to produce a game with only one or two voice actors, and maybe one (or half) of a rendered avatar. Not content to dwell within their limits, though, the developers have often excelled within their confines, doing the most with less. Firewatch, Sunset, Soma, Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, Gone Home, Event[0], and--to a certain extent--No Man’s Sky, are all experiments in solitude that have, to greater and lesser degrees of success, made their environments the story. In these games, the setting has to speak loudly enough to fill the void left by the absence of other characters. Such games also, by dint of their spartan design specs, tend towards a kind of videogame naturalism. They’re less concerned with the supernatural than they are with finding ways to make the ordinary interesting.

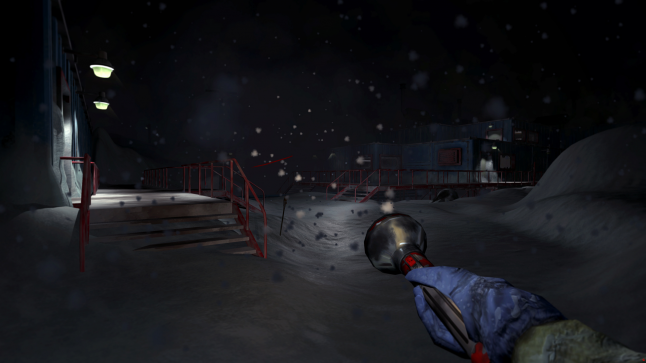

Into this crowded field enters yet another meditation on loneliness in the ordinary world: Orthogonal Games’ Near Death, a “game about survival” centering on an Antarctic pilot who crash lands near an abandoned polar research station and has to make do with threadbare supplies to live through an oncoming blizzard. The main enemy--indeed, the only enemy--is Antarctica itself. There are no demons, aliens, ghosts, or magical realism to animate the base, and Near Death is actually the better for it. It focuses tightly on a dynamic series of environmental challenges in a frozen base at the end of the world.

***

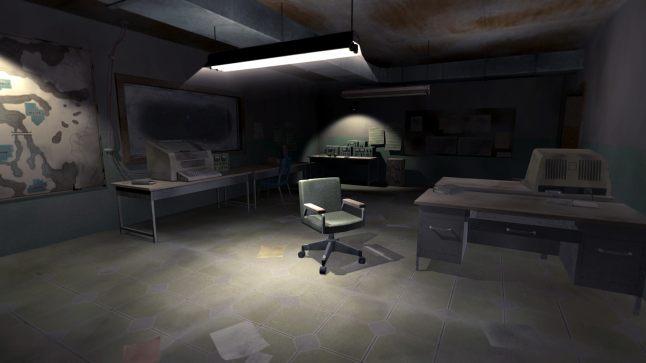

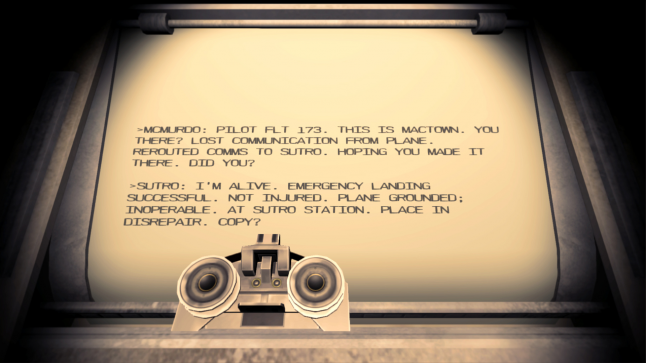

Tales of one person standing against an unforgivable wilderness make up a venerable sub-genre in literature, and Near Death is a worthy entry into the catalogue despite its overall lack of narrative and characterization. Pilot 173, the closest thing to a name we have for the woman you play as, is tough and cracks wise under pressure but we never learn much else about her, or the fictional Sutro Station that she has to cannibalize for her own survival. Normally this would mortally wound a game of this sort but, like the arctic survivalist you portray, it spins its scant available materials into something lifesaving.

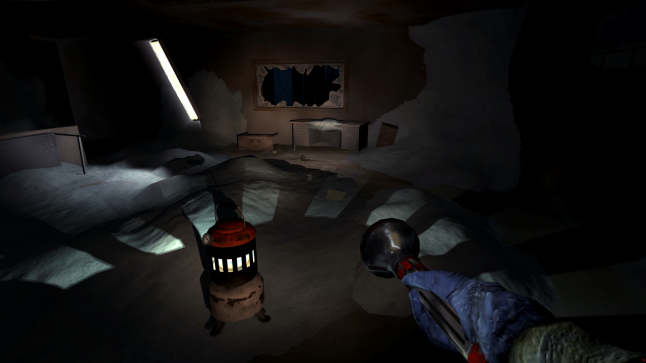

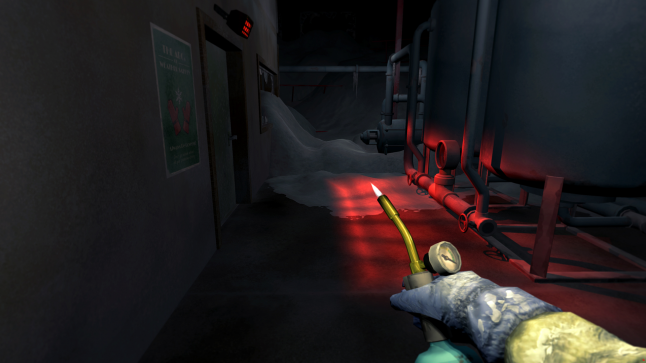

The mechanics are spot-on, and the game ramps up its difficulty in a ladder that scales with the growing intensity of the snowstorm outside, slowly allowing you to accumulate various skills, upgrades, and tactics in the process. The only thing you’re fighting is hypothermia; you’re constantly at risk of freezing to death and have to leap from one warm spot to another, often of your own hasty making. The storm, then, is not just a backdrop: it’s the setting, it’s your experience, it’s a character who charts the entire path of the game.

Near many of the doors that lead outside are large thermometers that tell you the outdoor temperature. You watch it plunge from -23 degrees centigrade at the time of your crash to nearly 100 below zero--a world record, if you’re keeping score. That precipitously falling thermometer, slashing the amount of time you can safely spend outdoors, is a drone of dread throughout the game. You quickly learn to respect the environment, as surely as actual explorers must, taking nothing for granted, double checking your compass heading and marking your path with rope and beacons amid the relentless winds.

Near Death succeeds at creating a taut and fulfilling experience, and the solitude actually helps with that. It enabled Orthogonal to make the most of the relatively small game environment--Sutro Base isn’t large, but there’s just enough space between its buildings to make trudging between them in hurricane force winds and white-out conditions a challenge in their own right. Suddenly a small space becomes painfully large indeed.

***

The lack of supernatural or horror elements tightens the focus on the environment; you need to stay warm, find batteries for your flashlight, and navigate between the buildings. The one thing you have to fear will kill you, and stalks you remorselessly; it seeps in through the windows, it makes your pulse quicken, and it will have you jamming buttons heedlessly in an attempt to escape it, but it’s simply the environment. Unpretentious and no more or less than it seems.

The best environmental storytelling uses a limited suite of mechanics to produce sensations in the player that match the scenery. I felt stress and panic in Event[0]’s spacewalks, and in the frantic rushes between buildings in Near Death. For games like this, such feelings are the entire ballgame. Their solitude keeps you firmly inside the protagonist’s head where no one can hear you scream.

“PURE UNTAINTED SURVIVAL, BABY,” cheers a player on the game’s Steam forums.

Near Death succeeds at this, and more than lives up to its title, describing the state you’re in almost constantly from beginning to end, teetering on the razor edge of life.

Unlike, say, Firewatch, this isn’t a psychodramatic game, and unlike Event[0] it is not a meditation on sapience and philosophy; instead, Near Death is about an ordinary person’s struggle to survive against an all too realistic foe. The terror you face comes entirely from within, and it is in this sense that the game allows you to truly inhabit the player character--a vital necessity in a game with very little dialogue to establish character otherwise.

The naturalism and realism of these games merits much praise as well; to one degree or another, they are about ordinary people struggling with something and finding answers or some measure of fulfillment--or simply surviving to the next day. In this you can make the triumph of an ordinary person feel as extraordinary as saving the galaxy, simulating a wider range of challenges than had hitherto been imagined.

***

This is a theme shared with games that are far less solitary, like Sundae Month’s Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor; here, the fantasy elements are fully restored to give us a “girlbeast trash-drone” in a buzzing, gritty Mos Eisley-style city. But the shift in perspective from epochal hero to portable-garbage-incinerator is both instructive and fun, reminding us all that we are far from exhausting the stories that can be told from this ground-level perspective on existence, and that games can allow us to inhabit these stories in a way that is both fun and meaningful. It has the added benefit of demonstrating that the experiences of working class people are worth telling stories about as well. Such games are, I think, a sign that our medium is just starting to go through its Impressionist period--and that’s all to the good.

When I last discussed this, I talked about how cities in games can develop intense moods and characters on the basis of a well applied theme--Shadowrun: Dragonfall’s anarchism, the sun-blasted canyons of WoW’s Orgrimmar, et cetera--and Sutro Station demonstrates how this can work even without the benefit of a city full of people, even without top-of-the-line graphics. It found a note--Antarctic Winter during the Endless Night--and kept hammering at it, varying the pitch and the key, but sticking to that central theme. The environment, however ordinary it is, can be powerfully expressive if you find the enchantment inherent to the mundane.

In Near Death’s case, it turned the experience of a deadly storm into an entire game, letting it become the spirit of the game’s entire setting. I felt this most keenly when trying to discern whether my intrepid pilot was about to freeze. At first I was irked by the lack of on-screen cues to tell me how close she was to death, and when her body heat had “recharged,” so to speak. But it was simply a matter of listening. She shivers and chatters; when she’s warming she’ll say “okay” or “that’s better” when she’s recovered. The lack of on-screen clutter and realistic cues, along with the lack of some kind of temperature meter, kept me focused on the experience.

Games like this exemplify Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s famous aphorism “perfection is achieved not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.” This minimalist credo is not right for every game, obviously. Some benefit from the sprawl of endlessly branching sidequests and mechanics within mechanics, or the depth of spreadsheets simulating gargantuan virtual economies, a la EVE Online. But for the indie game developer with few resources and few colleagues to call upon, it is a standard they can repair to.

Solitude is a limitation in which there is much freedom; so is naturalism; so is the stuff of ordinary life.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)