To prevent toxicity, design games with community management in mind

"Community is now, more than ever, an actual part of game design," argued Flaregames' Tara Brannigan. "It’s not something you staple on the end."

“When your game becomes toxic, your reputation precedes you,” UX researcher and advisor on online harassment Katherine Lo cautioned the audience during a talk at GDC this past week. She was one of four experts that offered advice to developers in attendance at the talk entitled “Mitigating Abuse Before It Happens” and, though the words of each speaker varied, the message was the same:

The best way to prevent abuse and toxicity (and keep your community management team happy) is to build the foundations for a healthy community directly into your game, rather than address issues as they spring up post-launch.

Many of the insights brought forward during the talk were centered around VR communities and spaces, but there are a number of takeaways from the session that can be applied across other areas of game development as well.

Lo argued that community management should be integrated into design and policy-making practices from the very start and that developers need to embrace proactive strategies to ensure their players both feel safe joining the conversation and don’t feel like they’re being penalized for engaging.

She explained reactive methods of community management can easily become expensive and taxing on engineering resources as developers try to both identify and fix problems that have already emerged, potentially derailing post-launch roadmaps and content releases while trying to remove a “toxic community” label.

To that end, Lo championed mid-development collaboration between different sectors of game development to best combat toxicity early on, arguing that community, trust and safety, and data science teams can work closely together to design systems like semi-automated flagging systems that highlight possible cases of harassment and elevate them to human agents.

Though she maintained that it’s important for those teams to have some level of understanding of what each arm of game development does; does your community management team understand how engineering works, like what’s expensive or cheap to implement and does your engineering team understand what community managers experience on the day to day?

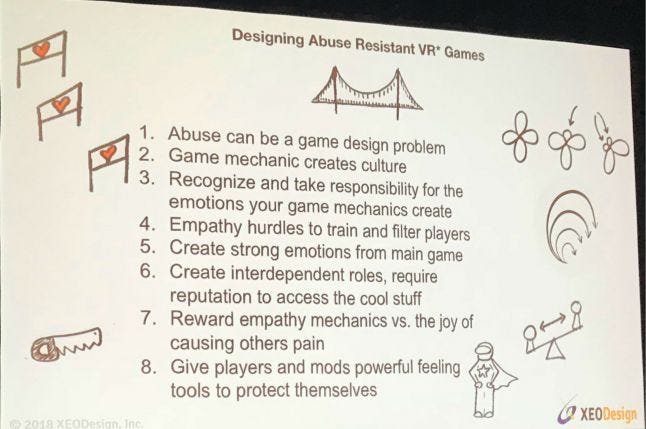

On the design side, Lo urged developers to “consider the way the mechanics in your game encourage cooperation and toxic behavior,” something XEODesign CEO and game designer Nicole Lazzaro then elaborated on in depth.

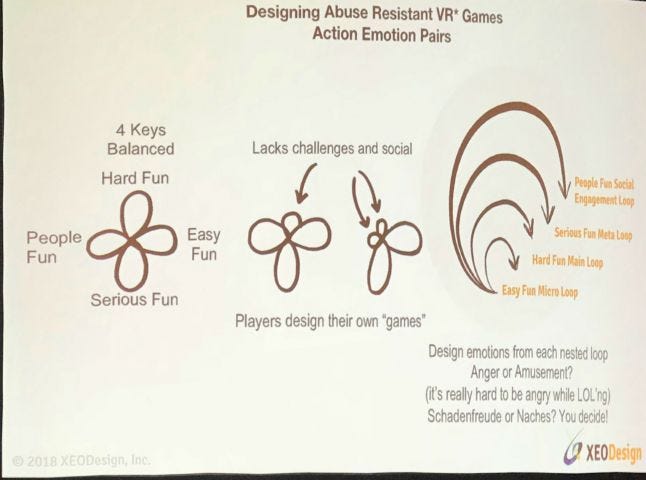

Those familiar with XEODesign may recognize the ‘4 Keys 2 Fun’ design philosophy that Lazzaro brought up during her portion of the talk. At its core, the ‘4k2f’ model highlights four kinds of fun (hard fun, easy fun, serious fun, and people fun) and associates emotions with each.

“In VR, emotions are deeper, stronger, and more personal,” said Lazzaro. “You can’t design emotions directly, but the mechanics and the emotions coming from those mechanics drastically change how your game is played.”

Lazzaro explains that the first step to mitigating abuse through design is to think about exactly what behaviors mechanics in your game reward. Not only is it possible to use game design to reduce the abuse in online communities, Lazzaro pointed out, but a lot of abuse happens because game mechanics are actually unwittingly encouraging it. She encouraged devs to think about their game as a funnel and look at what they’re bringing in that makes a game feel more inviting or less conducive to abuse.

She suggested developers introduce empathy hurdles (or mechanics that rely on trust, player interactions, or friendship) to reward cooperation with others. Using mechanics like this to instill values into online communities can proactively attract and encourage the desired core values of community behavior in a player base.

Lazzaro says developers should identify gaps in game design that may lead to potential abuse down the road. If one specific area of fun is lacking, for example, players may come up with their own ways to play and satisfy their own goals, sometimes at the expense of other players through activities like griefing or harassment. She encouraged developers to look at the emotions that are coming from such players during the short and long term and design challenges within the game to satiate those emotional needs.

Closing out the talk, Flaregames’ head of community and customer service Tara Brannigan offered developers some tips and examples from her own experience in the community management world that may help them effectively foster non-hostile communities.

One strong example she put forth came from Flaregames' Zombie Gunship Survival. In that case, the developers opted to tie players’ community account to their save file. If they got banned for uncouth behavior, they’d have to restart their save file, or petition the developers to have it restored. This significantly cut down on the amount of misbehavior in the game, Brannigan explained.

Here are a few more general tips Brannigan shared during GDC:

Give yourself time to understand what your community management strategy is (and give yourself time to figure out how to deal with behavior on different platforms)

Create really clear rules and terms of service

Act on those rules, or they don’t matter

Empower the good. Nail down what experience you want, then reinforce it.

Only responding to the misbehaving sends a message as well

Figure out what the worst case scenario is, both ethically and legally, and have a plan before it happens.

“You don’t know what you don’t know,” so have plans for the known situations so you have more time to deal with the wild ones when they pop up.

Developers, give community managers a career path, otherwise you’ll only have entry level community managers as folks with good experience promote up into other roles.

Your community managers and your customer service team should be different people; one builds the city, one puts out fires

Beware burnout; it’s a realistic outcome if devs don’t have the backs of their community team or value what they do

“Community is now, more than ever, an actual part of game design,” concluded Brannigan. “It’s not something you staple on the end”

Read more about:

event gdcAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)