Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

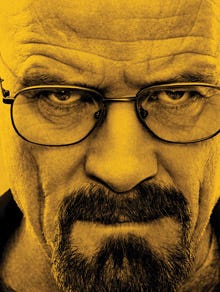

In this article, experienced game writer Susan O'Connor explores what a writer brings to the creative process, by analyzing hit TV series Breaking Bad -- as though she were in the kick-off meeting for its game adaptation.

February 12, 2013

Author: by Susan O'Connor

Experienced game writer Susan O'Connor (Tomb Raider, BioShock 1 & 2, Far Cry 2), explores what a writer brings to the creative process, by analyzing hit TV series Breaking Bad -- as though she were in the kick-off meeting for its game adaptation.

There are only eight episodes of Breaking Bad left. And then the show is over.

That is terrible news for fans, who can't help but wish it could go on forever. (Even show creator Vince Gilligan doesn't want it to end.) It's tempting to wish that someone could carry the IP forward, maybe into a console game...

Sure, the pitch would go: it's got all the elements. It stars an anti-hero; it elevates Walter's puzzle-solving ability to an art form; it's full of unforgettable villains. It could be the next Grand Theft Auto, starring Walter White...

No. That's a terrible idea. Whoever in that back room at AMC that ixnayed that idea did us all a favor. (They went with a graphic-novel game and interactive quizzes instead: good call.) Sky-high audience expectations would hamstring the console game developers into creating a pale imitation of the television experience in a virtual world, but successful IP adaptations smash a concept to bits and then recombine the wreckage into something both recognizable and utterly new.

It's risky. By sacrificing some of the best parts of a show or book or movie, you lose some of the original magic. The good news is that the loss forces developers to create new magic that only an interactive experience could provide. And that's the best reason to turn anything into a game.

Some developers (and IP guardians) are making brilliant choices when they adapt an IP. (Exhibit A: The Walking Dead.) The potential is clearly there -- for the right property, and the right approach.

I've worked as a writer in this industry for 15 years. I've been fortunate enough to be involved with projects from day one, for both original and adapted IP. Those experiences have helped me to develop a set of best practices that teams can use to unlock an IP's potential. In this article, we'll walk through a hypothetical kickoff meeting together, to if this adaptation has potential -- or if it's a disaster waiting to happen.

So: You're about to begin pre-production on a Breaking Bad video game. What do you do?

Step One: Analyze. What makes Breaking Bad so amazing? The whole is greater than the sum of its parts. But as you read Metacritic reviews, trends emerge. Here's what reviewers have called out, time and again, as part of the show's appeal:

Walter White is an everyman. As Stephen King says in his glowing review, "Breaking Bad invites us into another world, just as The Shield and The Sopranos did, but Walt White could be a guy just down the block, the one who tried to teach the periodic table to your kids before he got sick. The swimming pool with the eye in it could be right down the block too. That's exactly what makes it all so funny, so frightening, and so compelling. This is rich stuff."

His problems are real -- and so are the stakes. Walt's initial problem is as real as it gets. He's facing death. How will he provide for his family before he's gone? He faces real challenges in nearly every scene. In the show's second episode, he faces his first impossible choice: "Murder is wrong!" versus "He'll kill your entire family if you let him go." We don't know what he'll do -- or what we would do in a similar situation -- that's what keeps us watching.

The plotting is brilliant. Here's an exercise: watch an episode of the show, one you don't remember well. At the beginning of each scene, stop the playback and ask yourself how you would end it, if you were the writer. Then hit Play and watch what happens. Princess Bride screenwriter William Goldman once said, "Art needs to be both surprising and inevitable." Vince Gilligan's writing team delivers on both counts.

Walt is brilliant, too. He deals with disaster in clever (and often disturbing) ways. As Emily Nussbaum writes in the New Yorker, "Such problem solving has always been one of the show's great satisfactions, allowing Breaking Bad to feel as much like a how-to as a why-not-to... the audience can view events as a type of meta-puzzle: can the stakes rise even higher?"

The criminal underworld feels real. When Walter crosses over into the life of a drug lord, the world doesn't suddenly turn into a Martin Scorcese movie. The writers don't overplay their hand with dramatic lighting and heavy-handed music; they keep the action grounded in the dusty world of Albuquerque. The world has changed, but it's still a world we know.

The villains are unforgettable. Tuco! Hector! Gus! The Oatmeal breaks it down.

Then there's Jesse. There's the relationship between Walt and Jesse. There's the camera work, the comedy... I could go on. I bet you could, too.

Great! So much material to work with, right? Wrong.

Imagine a whiteboard. Divide it into two columns. Group your notes into two groups: Good Fit and Bad Fit. Decide which items on that list fall under Bad Fit -- for any number of reasons. For example, it's hard to create real stakes when the player can always restart the level; complex plotting is lost on gamers who leave the game for several weeks; you'll lose Bryan Cranston's onscreen charisma...

A lot of the items on your list will fall under the "tough" category.

"But wait!" You're saying. "I can think of a way to ______..." Yes. With a lot of hard work and clever tricks, theoretically anything is possible. But some parts of the show just lend themselves to a game -- and others don't.

As experienced gamers and game developers, you can trust your gut here. To keep your kickoff meeting moving, don't get bogged down in convoluted defenses of ideas. Just take a first pass at your Bad Fit list and (for now) set it aside. That leaves Good Fit. Later on in the process, you'll know which elements are worth fighting for.

At this point in the kickoff, the designers would be elbow-deep in ideas around agency, immersion, and multiplayer possibilities. This article is focused on what a writer, rather than a designer, would contribute to the kickoff, so brilliant design insights will have to appear in the comments.

But to touch on game mechanics: Choose your verbs. What will the player DO in this game? Let's say, for argument's sake, that the people who greenlit this game love Grand Theft Auto, so they want an open-world game. Now imagine the player is Walter White. Imagine him runing through the streets, gun in hand. Hold the image for a second. Doesn't seem right, does it? Walter's a smart guy, calculating. Will your game reward impulse behavior? Do game mechanics line up with personality? That leads us to the next question...

Who is the player character?

Who is the player character?

"Walter," someone says!

Are you sure?

Ask what personality traits a character would need to succeed in your game. Not the story: the game. Think about what the player's avatar will be doing when the player presses X; imagine those events taking happening in the real world, and then ask yourself what kind of person would be able to manage your demands.

Your man might need to be physically strong. Morally ruthless. Action-oriented. Impulsive. Scared of cats. Whatever! Come up with your list, compare it to the cast of characters from the show, and find out who you've been describing.

Walter is an indelible character with a complicated inner life. If the player took control of him, all of that nuance could be lost. It could make more sense to play with Walt -- as Jesse -- or against Walt -- as a competing drug lord. Even Hank is a contender. Ironically, Walt -- the heart of the show -- is the WORST candidate as a player character. That is just another example of how IP adaptations can be so counterintuitive.

Let's say for argument's sake that somebody in the room is hell-bent on using Walter. Okay, let's consider it. Walter doesn't have a lot of fun -- and when it comes to games, fun matters. He certainly doesn't DO nearly as much as he THINKS. Is your game a thinking game? Or an action game? (In AMC's graphic novel, you take on the role of twitchy Jesse instead of cerebral Walt.) And so much of Walt's early story is about not being in control. Will the player accept a low-status, weak avatar?

But of course, Walt isn't always a low-status guy on the show. More on that, later in the article.

It's a truism that in most video games, the world is the most important character. The player spends more time interacting with the physical environment than any NPC. So world development is more important than character development. (That is a devastating sentence for most writers, by the way). Make a list of the Breaking Bad environments and ask yourself which ones the player will want to explore.

To get the conversation going, make a three-column list. In the first column, list as many show locations as you can. In column two, list seminal show events that happened there -- like Jesse's basement, where Walt killed his first victim, or the pool where Skyler pretended to drown herself. Those are the ghosts that will come up for the player in those environments, and that creates emotional resonance. In the third column, list things the player COULD do there, based on your game mechanics. Before long you'll see which environments lend themselves to your game design -- and which ones won't.

Let's say that there's not much in the way of gameplay that could happen in the White family home. So you either limit the home events to cinematics -- which, of course, most players will skip -- or you eliminate the house altogether. But that means taking Walter White's home life out of the game equation.

How does that impact the emotional core of the experience? What do you lose? Walt's family is his justification/rationalization for all the crimes he commits. Without that, where is the moral center of your game? Maybe you shift the Walt/Skyler conflicts to phone calls that take place while the player is driving around -- but then Skyler is reduced to the nagging wife, a stock character the player will most likely ignore.

That's not to say that you should shoehorn in Walt's house for story reasons. But recognizing what you're sacrificing, early in the process, will help you to make smart creative decisions during the chaotic crunch of production.

Some locations, like Los Pollos Hermanos, are tied to specific seasons. Which brings us to the next question...

Where does your game take place, in relation to the show's timeline? This question matters more than it does for most TV shows, for a simple reason -- Walt changes. This is unusual for a TV show, which is a medium that usually showcases character depth over character change. To illustrate the point, watch the first and last episode of The Sopranos. Has Tony changed? Well, he's gained a lot of weight. But otherwise, he's the same guy he always was. He never overcame his core problems, despite all that expensive therapy. The difference is in us, the audience -- we know a lot more about Tony in the end.

In his pitch for Breaking Bad, Vince Gilligan promised to take Walter White from Mr. Chips to Scarface. In other words, Walt goes from good guy to bad guy -- from protagonist to antagonist. At this point in the series, a lot of viewers have turned against Walt -- even though they still love the show.

So which Walt will you deliver to the player? The family man, facing his mortality? Or the Walt of today, Heisenberg -- the Tony Montana of Albuquerque? Walt as hero, or Walt as villain?

One way to answer that question is to decide what kind of a relationship you want your player to have with Walt. Enemy? Friend? Sad sack? Cipher? That relationship will help define the emotional resonance of your game.

Finally, how do you connect with the material? Bring your own passions to the project in order to find the story you want to tell or the experience you want to create. In a recent kickoff meeting I attended, the lead designer drew on his experiences growing up in the UK, listening to American hip-hop. That music changed his ideas about what life was like in America. Those memories fed right into his game design and brought it to life.

Your willingness to commit -- and to reveal yourself -- can have a ripple effect throughout the team. In a recent interview, Vince Gilligan said, "It does seem to me wisest to not be too much of a quote unquote 'auteur,' but to let these wonderful directors, these actors, these writers and our wonderful director of photography and our production designer, all have their enthusiasm for the show to give their all to it."

At the beginning of this article, I showed my hand and told you that I thought a console game based on Breaking Bad was a terrible idea. When I ran through this analysis myself, I concluded that the losses outweighed the gains.

But to be honest, I'd love for you to prove me wrong -- because I am really going to miss this show.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like