Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In a video game, veteran designer Cook suggests, each player is just like a pachinko ball, "moving on their unique path" through gameplay - and he presents the results of a fascinating recent 'think tank' on game story's evolution and future.

Late last year, a select group of experienced game designers, the unicorns of the game development profession, gathered at a remote ranch in the dusty hills of Texas. Their purpose? To solve the great game design issues of the coming decade. The event? Project Horseshoe, organized by Game Developer Hall of Famer George "Fatman" Sanger.

If you've been to GDC, some of your best moments will have likely been those crazily intense impromptu conversations that coalesce in the halls between sessions. The best way I can describe the essence of Project Horseshoe is to imagine an entire weekend of that sort of deep mind meld. Game designers, it turns out, love talking with other game designers. Upon meeting sparks fly, instant friendships are formed, and wildly dangerous ideas are discussed with great freedom and vigor. Add to the mix fine liquors and a Reagan-esque arsenal of projectile toys, and you have an ideal environment for brilliant discussions.

There is a structure. Groups self-organize with the help of some talented facilitators around topics of mutual interest. This year we saw one group form around creating the next generation of designers and another focused on game designs to yield alternative emotions. At the end, the groups are required to generate human-readable reports that are posted on the Project Horseshoe website for all to see.

There is a structure. Groups self-organize with the help of some talented facilitators around topics of mutual interest. This year we saw one group form around creating the next generation of designers and another focused on game designs to yield alternative emotions. At the end, the groups are required to generate human-readable reports that are posted on the Project Horseshoe website for all to see.

The goal, despite the highfalutin nature of the event, is to create some very practical steps for changing the gaming world. The work of the attending designers will likely influence millions of players over the coming years. Of all the groups in the industry, senior game designers have a unique opportunity to promote new ideas and set forth a vision of how future games will be played.

This year, I participated in a session on that hoary old chestnut known as "story". Here's a brief report on what we discussed behind closed doors. This was the highly collaborative effort of about 10 different designers. We got stuck, we argued, we stayed up until 2 AM hashing out differences perspectives. What impressed me in the end was the passionate belief shared by everyone at the table that games are just starting to come into their own as a medium that has immense power to change the world, for both better and for worse.

"Story." Now there is a word with immense baggage. For tens of thousands of years, people across the world have been telling stories to one another. The most respected and vibrant arts across all of human history involve traditional narrative storytelling. Our designers are steeped in the lore of movies, novels and comics. Many of our earliest, most influential games, like Zork or Adventure, are shown to the user as stories. Our blossoming new field of game design constantly finds itself forced to answer the question, "How do games and story intersect?"

Perhaps we are tackling the wrong problem.

We believe that game designers are in the business of experience creation rather than that of storytelling. The story that is generated through gameplay is the player's personal story that has been mediated by the game systems.

This is a rather substantial shift from the concept of the auteur sitting down and penning a tale of love and despair. Instead of writing about passion, our goal is to help the user experience passion. Instead of describing fear, our goal as game designers to is cause fear. We construct systems, whirling social and mechanical environments that lead, poke, prod, react, connect and encourage the player to reach, out of their own free will, a peak physiological and mental state.

Out of this experience, the player constructs their own very personal story. They digest the experience. They link the pieces together with their past life lessons. In the end, if the gelled memories of the game were rich with meaning, they'll share their narrative with others. Hearing our players' stories burst forth from our game is the clearest possible signal that we created a great experience. And yet, we must never lose sight that these stories are secondary effect. Story is the tail of what we do as designers, where the mediated experience is the dog.

Throughout our discussion, the one key visual that resonated with all the experienced designers in the room was the "Watery Pachinko Machine of Doom." In a pachinko machine, dozens of ball fall on pegs and bounce about in a chaotic motion until they finally reach the hole at the bottom of the machine. When you add thousands of balls, to the point where balls are like individual water molecules, the patterns of where the balls flow throughout the system becomes more apparent. You see currents and waves of motion.

Each of those balls is a player, moving on their unique path. As designers, we build the machine and analyze broad patterns of motion through the system. Instead of the pachinko physics of collision, we calculate the physics of human psychology.

There are a broad range of tools and systems that can be used to create the successful mediated experiences. Many are well known and we've included a list of currently used support techniques/tools in the appendix of this report.

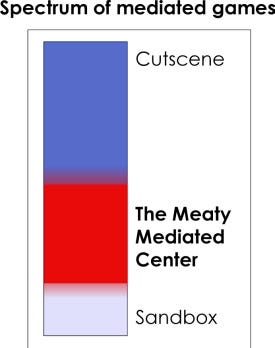

However, with such a diverse and experienced group of people present, we soon turned towards exploring new methods of creating mediated experiences. Games range from 40-cutscene choose-your-own-adventure games to sandbox game where all you get is a sternly worded command from your mother, "Go out and play!" We are interested in the meaty mediated center of the spectrum.

With the vague and divisive word "story" focused into a more palatable discussion of "the meaty center of mediated experiences", we spent the rest of our time on three topics:

Examples that play outside the current rules of the game industry: What are examples from that wild that we can study to give us practical insight into how mediate experience can be built?

Models for supporting player emotions & experiences: What are some conceptual models that we can adopt that helps us understand mediated system at a more fundamental level?

Vexing problems: What are the big problems that still need to be discussed further?

Many of the most exciting techniques for generating interesting experiences are found outside of the game industry. Academia, advertising and independent games have been dabbling in these ideas for years. We focused on rich examples from Alternate Reality Games (ARGs), narrative spaces, and social networks.

Alternate reality games such as I Love Bees and Last Call Poker have found that breaking the barriers between the online game world and the player's real world can lead to extremely compelling experiences.

Patricia Pizer shared a tale of how they included a simple game mechanic in Last Call Poker that required players to take a picture of a gravestone where someone had died on the same day they were born. Figuring this to be a rare occurrence, the game masters were shocked to find their inboxes flooded with dozens of images. Players were going to graveyards and taking pictures of the graves of infants that had been stillborn. The intense emotional impact of this intersection of game mechanics and the real world left a lasting mark on both the players and the designers.

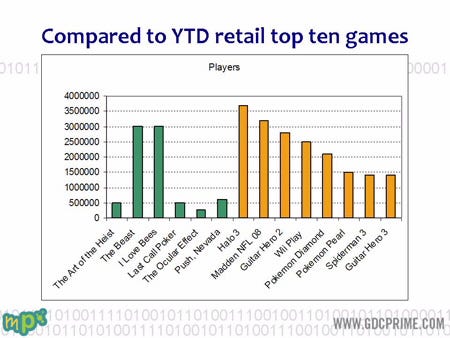

ARGs numbers compared to top retail games.

Raph Koster's GDCPrime 2007 lecture "What are we missing?"

Some lessons from ARGs include:

Difficult to scale: It is difficult to make the experience scale well since it requires active game/puppet masters playing various roles and adjusting the game to account for the player's unexpected progress. ARGs are ultimately a highly leaky pachinko machine.

Breaks players expectations of a game: However, the emotions that result are intensely powerful because ARGs actively break the model of a traditional computer game player experience. Players expect to play a game, but they end up being confronted by very meaningful and real situations.

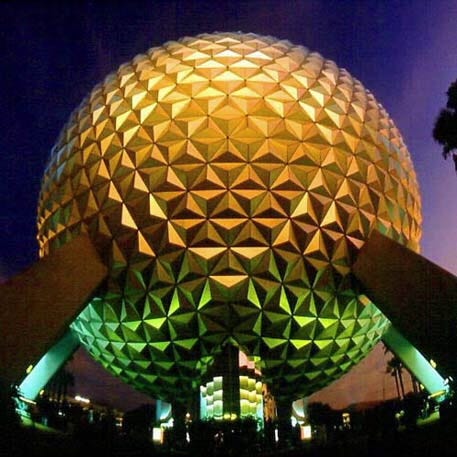

There is a long history of environmental spaces that tell a story. Disneyland, Location Based Entertainment (LBE) and amusement park rides have been successfully creating mediated experiences for over a century.

Ceci n'est pas une golfball. It is a carefully designed visual goal.

Lessons from narrative spaces include:

Controlled reveals/sightlines: Structure your space in such a way that intriguing goals are clearly presented to the customer as they wander aimlessly. People will tend to make their way towards the visual goals and thus will be guided even though they are acting out of their own free will.

Established paths: By combining sightlines, you can create well trodden paths that users will move through while still imagining that they are exploring new territory. This allows you to focus the majority of your production effort along these paths. A good example of this in games is what Naughty Dog has done with Jak and Daxter.

Various forms of social networks ranging from MySpace to Match.com are turned to connect people and encourage meaningful relationships. As highly social animals, people find almost any interpersonal interaction to be highly meaningful.

Systems for bringing people together: The surveys on dating sites help connect people of similar interests. There is interesting work going on analyzing the hubs of various social networks and setting up events that causes hub roles to collide with one another, smashing together entire social groups for immense dramatic effect.

System for maintaining relationships: Existing relationships must be groomed through the use of gifts, notes and idle chatter. Systems like Twitter or the newsfeed in Facebooks are excellent examples of these systems in action.

Social networking design challenge:

Make a game that replicate the joy of a good Tupperware party.(They are so happy!)

These were areas that weren't discussed as in depth, but also offer powerful techniques for mediating the player's experiences.

Reality television: Reality television shows, ranging from moderately mediated examples like Survivor to heavily mediated competitions like Dancing with the Stars, offer inspired example of how to use environmental and psychological manipulation to create intense human drama. As ratings demonstrate, a real person actually falling in love can be more appealing than an actor pretending to fall in love.

Rituals: Throughout history, various religious and cultural groups have used ritual to create deeply meaningful experiences that resonate across generations. One topic we discussed was Aztec sacrificial rituals and their impact on an entire culture. With their intricate rules, reward system and extensive use of the magic circle, they have many hallmarks of a social game, albeit one with serious real world consequences. It is worth studying what makes rituals so powerful and contemplate how those lessons could be applied to games.

As we dig further in each of the examples above, it becomes clear that there is an underlying psychology behind many of the successful game systems. By understanding the science of what we are attempting and then applying experimental methods, we can ensure that our games product their intended effects by designer choice, not accident.

There are numerous predictive psychological models that we can adopt that help designers understand how players will react to various stimuli.

Theories of emotion: What causes emotion within the player? There is a large body of academic work that describes the connection between memory, recall, emotion and decision making processes.

Organizational psychology: How do group dynamics evolve? Organizational psychology is the study of groups and how change occurs within groups.

Psychophysiology: "Psychophysiological measures are often used to study emotion and attention responses in response to stimuli. Loud startle tones, emotionally charged pictures, videos, and tasks are presented and psychophysiological measures are used to examine responses" -http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychophysiology

AI modeling of players: Many of these academic techniques gain immense value when they are turned into AI routines that attempt to predict the player's behavior. Instead of turning loose a hundred players in a new level, you can instead turn loose a hundred AI driven bots. For many situations like line of sight modeling or even prediction of how social networks evolve, AI's are remarkably effective at generating short term predictions.

Basic game design is a highly iterative activity that requires the designer to make educated predictions, test those predictions and then adjust the design. Unfortunately, our measurement techniques are currently quite crude.

Biofeedback: The direct measurement of emotion through biofeedback systems can give designers a detailed understanding of how individual players experience the game. Skin conductivity and heart rate variance are two promising low-cost options.

Skill chain-based logging: The indirect measurement of fun by logging the player's interaction with known learning opportunities can alert the designer to flaws in the flow of the game. This technique works well across large populations of players.

Social graphs: Many social networks contain an immense amount of information about who each player interacts with, how long they interact and what key words they use. This data can be fed directly into a reputation-focused AI model and used to tune the AI so that it becomes incredibly good at predicting what will happen. Imagine being able to get an overview of guild conflict or player defections a day or more in advance. In effect, you can predict the social weather of your online game with ever-increasing accuracy.

During the course of the discussion several difficult problems were mentioned that we would not be able to solve, but were worth highlighting. These include scaling high touch experiences, the role of authorial voice, and ethical issues,

Mediation of player experiences ultimately leans towards creating psychological situations where players choose of their own free will to act in a desired manner. In ARGs and narrative spaces, the most powerful tool available is the puppet master, a human actor who guides and adjusts the experience to the player's current needs. Many years of experience have taught game designers that players will always react mostly strongly to the prods, suggestion and presence of other human beings.

Unfortunately, finding skilled people to fill these mediation roles is time consuming and often futile. It is a new role that most practitioners stumble upon by accident, not one supported by schools or trade organizations. Once you do find a competent game master, you run into problems of scale. A single game master can handle a few hundred players in an emotionally meaningful manner. With games hoping to reach millions of players, all those game masters start costing you big bucks. High touch experiences, mediated by live human beings, are exceedingly costly.

Luckily many puppet master activities are relatively mundane, such as giving new quests or acknowledging the completion of real world activities. Also, they are time limited to a few minutes or less of actual contact with the players. This has lead several participants in the group to attempt to create high touch experiences by building emotionally engaging, highly social NPC characters. General purpose AI is an unsolved problem, but perhaps if we limit the scope of what we are attempting, we can create an effective helper.

The Shrike: We all need a little AI Jesus to help us make the right decisions

The goal is to have each game master control a herd of AIs that handle most moment to moment interaction with the player. Based on the user responses, computer simulations can be run of the user's mood, and the AIs can adapt their responses accordingly. Extreme situations can be brought to the Game Master's personal attention, at which point the GM can seamlessly take over. The entire time, the person on the other end operates under the assumption that they've been talking to a real human being.

Attempts thus far build on the psychological models of the player we mentioned earlier. Designers build proactive NPCs that poke and prod the player in ways the AI models suggest will result in desired behavior. Current research in this area includes:

Building believable personalities that include inconsistency, unreliability, etc.

Ensuring that the NPCs are goal-oriented with long-term, deep agendas.

Focus on opportunities for influence mechanics rather than combat/conflict.

Generating artificial social structures, populated by AIs that create social norms and goals for the player to operate within.

Giving AI's knowledge of player's existing social graph in order to inform NPC decisions. For example, the AI might suggest that you, as a powerful guild leader, form an alliance with another powerful guild leader whose group is becoming too isolated and risking dilution. This creates meaningful conflict that adjusts the layout of the social network in predictable ways. The AI is ultimately playing a strategy game that involves manipulating and cultivating the social graph of the player community.

With such tools, the hope is that a game masters can use its socially-aware NPC army to support thousands of players in a high touch, emotionally meaningful manner.

Game designers are artists with vision and their own personal voice. If games are experiences where the most active voice will be that of the players, what opportunity is there for designers to express their authorial voice? How do we identify our Steven Spielberg or Orson Welles? Historically, such iconic voices are rare in the game industry.

Perhaps we are looking in the wrong place. In games, the voice of the designer becomes less about having a unique narrative style than it is about using various types of game systems in a distinctive fashion. In this light, you can easily observe the unique voice of industry luminaries that extends beyond simple genre classifications:

Jeff Minter with his psychedelic retro shooters.

Shigeru Miyamoto's teams and their crisp mechanics of exploration and skill acquisition.

Will Wright's teams and their micromanagement heavy simulations of everyday life.

Once you begin looking at authorial voice from this perspective, new opportunities become apparent. Instead of asking "What type of characters or narrative do I want to put in front of my audience?" you instead ask "What are the cultural values and common emotional touch points that our team wants to encourage in our player community?" This is most evident in multiplayer games, but the same decisions apply to single player experiences.

Ron Meiners told a tale of how while serving as a community liaison for an online game, he always made sure to talk publically about how the group was surprisingly helpful and generous. Overtime, this strategy of highlighting and socially rewarding desired behavior was adopted as a standard practice within the community. As a result activities such as trolling, griefing and other common negative social behaviors popped up only rarely.

There are two fascinating aspects of this example. The first is that authorial intent is exercised through active social engineering. Again, the designer is playing with systems, albeit social ones instead of merely mechanical ones. The second aspect is that the players themselves take an active role in magnifying the designer's message. The player-base acts as a "greek chorus" that guides and informs the individual players.

Lesson here include:

Community norms shape the players voice. Designers and community liaisons assume immediate roles of authority and through their actions, set the tone for the community.

Belief creates behavior. The designer is in a unique role to codify, promote and reward desired beliefs.

What are the ethics associated with the type of massive, intentional psychological manipulation that we are contemplating?

The Stanford Prison Experiment: Is this appropriate game mediation?

Much of what we are discussing is not so different from the infamous Stanford Prison Experiment. In the 1970's, two groups of apparently well-adjusted students were put in a simulated prison. Some were randomly assigned as prisoners and others were assigned as guards. After only six days, the researchers called off the experiment due to evidence of sadism, depression and intense prisoner stress. The act of putting good people in an evil environment resulted in behavior most would deem immoral.

There is obviously a spectrum of moral behavior possible in a mediated experience. At one end you have the relatively good-hearted Dancing with the Stars where everyone proclaims it to have been an empowering experience. At the other, you have game designer created situations like the Stanford Prison Experiment where the design provokes the dramatic and life altering psychological breakdown of the players. Heaven forbid game designers get into the business of mock human sacrifice.

There are already a few voices in the game design community, such as Jonathan Blow, that are actively decrying the game design techniques used in popular online games as unethical. On the other side, capitalistic forces are pushing teams to build ever more intense and addictive experiences. The ethics of mediated experiences is a topic bound to spawn passionate debate over the coming decades.

The group covered an immense range of topics in our two brief days. We ended the conference with the clear understanding that expanding these thoughts further would require an ongoing conversation.

To that end, the group is creating a website called FabulaRasa.org that serves as a focal point for our discussions. The name roughly translates to the "blank story", an empty vessel for our players to pour their tales into. Our hope is that experienced game developers and researchers will contribute to building a rich repository of essays, papers and discussion on creating mediate experiences in games.

This report captures only a small fraction of the conversations that took place at this year's Project Horseshoe. I heartily recommend you visit the website and check out reports from this year and previous years.

This paper was the collaborative effort of all the people listed below.

Facilitator: Linda Law, The Fat Man

Stephane Bura, 10tacle Studios Belgium

Daniel Cook, Microsoft

David Fox, iWin

Tracy Fullerton, USC Interactive Media

Victor Jimenez, Northrop Grumman

Ron Meiners, Multiverse

Mirjam Palosaari Eladhari, Gotland University

Patricia Pizer, Disney Interactive Studios

Mike Sellers, Online Alchemy

Mike Steele, Emergent Game Technologies

The following were items that influenced or where mentioned during the discussion.

Project Horseshoe, George "The Fatman" Sanger and crew

http://www.projecthorseshoe.com/

Constructing Artificial Emotions, Daniel Cook http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/1992/constructing_artificial_emotions_.php

Chemistry of Game Design, Daniel Cook, http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/1524/the_chemistry_of_game_design.php?print=1

Stanford Prison Experiment, http://www.prisonexp.org

Understanding rituals through the work of Claude Levi-Strauss: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_L%C3%A9vi-Strauss

Why we play games: Four keys to more emotion without story, Nicole Lazzaro

http://www.xeodesign.com/xeodesign_whyweplaygames.pdf

What are we missing, Raph Koster

http://www.raphkoster.com/2007/12/06/gdc-prime-2007-what-we-are-missing/

Story Construction and Expressive Agents in Virtual Game Worlds, Mirjam Palosaari Eladhari http://intranet.tii.se/components/results/files/eladhari_lindley.pdf

The soundtrack of your mind: mind music - adaptive audio for game characters, Mirjam Palosaari Eladhari http://mirjame.googlepages.com/Eladhari_Friedenfalk_Niewdorp_ace_20.pdf

The Daedalus Project, Nick Yee

http://www.nickyee.com/daedalus/

The following is a laundry list of traditional techniques that games have been using for decades. Think of these as mediation 101.

Basic plots: Common plots such as the '39 Plots' that have known effects on the audience.

Hero points: Resource that bends plots to the user's needs (or Villain points). Used as a storytelling resource. Alternatively, Whimsy Cards

Storytelling Patterns: Such as Pattern language by Christopher Alexander

Reversals that are heuristically created

Modularity

Hierarchical

Character Development of both NPCs and the player character.

Customization of various elements of the game.

Emotion Management

Music

Ambient effects

Environments with emotional connotations (such as a haunted mansion)

Exposition including cinematics

Relationships ties chars together through game play mechanics, different roles, access, organization

Novelty

Mechanics of player progression

Manipulation of Game Economics

Voice/Style

Manipulating Time (compressing/style)

Manipulation of Player's Perception

Switching POV

Treating the group as a character

Collaborative puzzles

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like