Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

What makes Virtue's Last Reward one of the best storytelling games of all time? Gamasutra speaks to director Kotaro Uchikoshi and analyzes the gameplay to uncover the secrets that make this suspenseful graphic adventure tick.

Of all the story games I've ever played, Chunsoft's visual novel for 3DS/PlayStation Vita Virtue's Last Reward stands at the top of the heap: it's storytelling as gameplay, not beside it, and that significant fact earned it a place on Gamasutra's games of the year list for 2012.

The story is complex and rich, with multiple branching paths that all lead seamlessly to a single conclusion; because of this, it has all of the features that make linear narrative compelling while offering up a palette of choices that invite you to piece together what's going on by continuously testing the story's boundaries.

Virtue's Last Reward

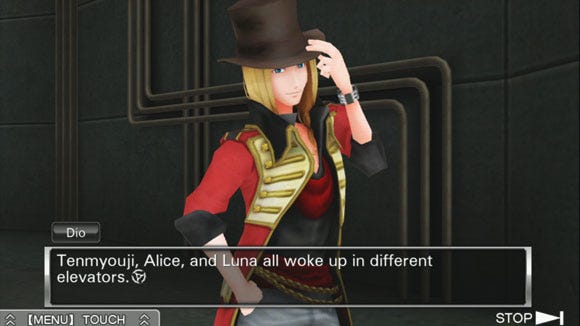

If you step back and consider how the game really works, you'll find that you have no meaningful bearing on how the story plays out. This matters less than it sounds like it should because of the role it casts you in -- a kidnapped college student who has no idea what's going on. As you learn, he learns; as you figure out what's going on, so does he. The player is deftly kept aloft in the updraft between what just happened and what's going to happen.

What's the secret to building a story game like this?

"When I am writing a story, I always have a conversation with an imaginary player. It makes the process more fun," Kotaro Uchikoshi, the game's director, tells Gamasutra.

Virtue's Last Reward is what is known as a visual novel, the Japanese form of the graphic adventure genre, which, as in the West, has its genesis in 1980s PC games. Uchikoshi has been working in the game industry since the 1990s, when he landed at one of the genre's major proponents, the now shuttered KID.

999: Nine Persons, Nine Hours, Nine Doors

He launched his career as a freelance writer and developer in 2001, eventually partnering with Chunsoft, a developer with a rich history in the genre, to create the Zero Escape series, which includes 2010's 999: Nine Persons, Nine Hours, Nine Doors (Nintendo DS) and 2012's Virtue's Last Reward (Nintendo 3DS, PlayStation Vita).

Both games put the player in the shoes of someone trapped in a contest, called the "Nonary Game," played out in a sealed environment, where they and eight others must escape to survive, and will die at any time if they break the rules.

In Virtue's Last Reward, the player is, in fact, constantly aware of the threat of death -- from the premise of the Nonary Game itself, to the themes of epidemic, murder, and terrorism that weave through the plot.

As players, we all know that death is nothing to fear; in games, we die all the time. In fact, Uchikoshi acknowledges this. "For games, regardless of the genre, the main character and surrounding characters can die many times. The weight of a character's 'death' may somewhat be taken lightly, and that is one of the weak points of games."

He has an antidote for that.

"So basically, rather than the desire of 'I don't want this character to die, so I'll try to avoid it,' we put emphasis on the desire 'I don't want this story to die as is, so I'll try to avoid it.' As a result, keeping the story alive will connect, in a way, to avoiding the death of a character," he says.

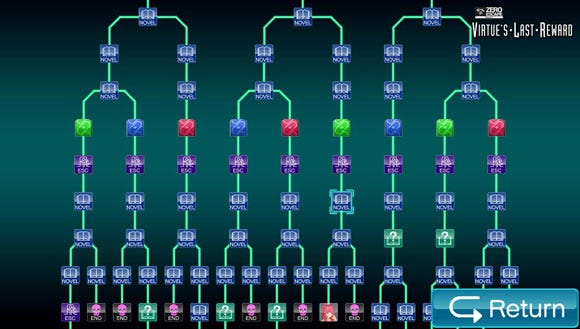

Cleverly, this turns the player's emphasis toward keeping the game's story moving forward. In fact, the story's branching scenarios -- which are represented by the in-game flowchart below -- are a large part of what makes Virtue's Last Reward such a significant achievement for game narrative.

This is not a mere play log; it's fully interactive. Players can jump to any point in the story they've reached so far, testing theories and exploring alternative outcomes. The threads of the story branch as you make decisions and change what happens.

The best bit is that you can take this knowledge into other threads and, armed with it, learn even more. As you do so, the tale begins to reveal its true depth in surprising ways -- when characters both do and don't act as you'd expect, it gives you more food for thought, and more knowledge to take back to other scenarios.

As the game approaches its conclusion, more and more of the story unravels, allowing you to grasp those threads and weave them together into the real tale.

There's also a key element to the decision-making process in Virtue's Last Reward; however, it's easy to overlook this as a player. "In my works, I feel like it's more common that the decision they made was super important after they made it rather than before they made it," Uchikoshi says.

On reflection, this may be the most important distinction between Virtue's Last Reward and other choice-based story games. In The Walking Dead, for example, your decisions generally have immediate effect, with small ripples into the later chapters of the game. In Virtue's Last Reward, however, you only understand the effect your decisions had in hindsight, as more information becomes available. This keeps the suspense level high and, perhaps even more importantly, avoids those awkward scenarios in which your choices, as it turns out, didn't matter at all.

In developing games -- as opposed to simply writing stories -- Uchikoshi sees one crucially important distinction. "There is one thing that games have that isn't present in any novel, manga, movie, anime, or drama, and that is what I call 'bi-directionality,'" says Uchikoshi. "A story that doesn't flow in a single direction -- that is the essence of a game scenario."

"The 'bi-directionality' I am talking about refers to the fact that there is interaction."

What sets Virtue's Last Reward apart from its predecessor, which has a similar premise and follows a similar format, is that flowchart -- the ability for the player to jump around in the story at will.

Rather than any decisions made within the context of the story, the interesting moments of player agency derive from what thread of the story he or she chooses to explore, and when.

As the threads reach their conclusions, new avenues open up. Some, rather than concluding, are merely blocked due to a lack of information on how to proceed. The player can actively search for the keys to these "locks" within other threads in the game's scenario. The keys are always information: you'll understand why something happened when you explore it from another angle, and then be able to proceed.

"In a novel or movie, the reader/audience member can be no more than an observer of events, but in a game you can take the role of the main character. In addition, having the player experience things from a first-person perspective rather than a third-person perspective gives the game a stronger impact and makes it more interesting," Uchikoshi observes.

He uses this trick of perspective not just to keep the player engrossed, but also to limit the player's knowledge in a realistic way -- you can only ever understand what you experience or are told. This then becomes an underpinning of the unfolding of the game itself, as parallel story tracks that spiral off in different directions offer avenues into information you could not have otherwise discovered.

There's not just the challenge of keeping player interest through so many paths; there's also the avoidance of repetition and fatigue. "I tried my best to have all of the scenarios develop differently with different outcomes," says Uchikoshi. "You have to provide a certain amount of motivation to make a player want to play through all nine scenarios. That part was very challenging."

Uchikoshi designed the game's story flow using Excel, prototyping the potential outcomes of in-game scenarios. "After that, I matched the results with the chart I made and then came up with the nitty-gritty stories. When I came across situations that I couldn't get to work story-wise, I rewrote them in the Excel file."

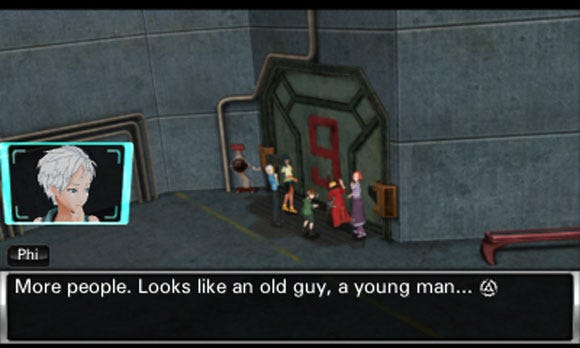

VLR's number 9 door

In VLR's Nonary Game, if any of the participants can open the door with the number 9 on it, they can escape. The only way to open this door is to get enough points -- and to earn points, the participants must blindly choose to ally or betray each other in the "AB Game" -- a game of trust.

Deciding what would happen in these AB Game scenarios complicated things for Uchikoshi. After deciding on the flow of the story, he says, "I then tried my best to balance out various results from the AB Game... However, if I changed the results of Round One, then everything in Round Two related to that result had to be changed, too. That part was very hard."

These AB Game decisions form the crux of the direct player choice system in Virtue's Last Reward, and much of the interpersonal conflict that is the engine of the game's character interactions.

This setup may sound extremely far-fetched -- and it is. But the internal logic is what matters, not the plausibility of a given scenario, Uchikoshi argues.

"The easiest answer to this question would be 'As long as it's interesting, anything goes!'" he jokes. "If the story is interesting and you can immerse yourself into the world, the 'implausible' becomes 'plausible.' It's strange, isn't it? It becomes plausible in the player's head."

This has a dangerous flipside. "On the contrary, if you try to make the 'plausible' more plausible, and you give a forced explanation to justify it, the story instantly becomes boring, and the 'implausible' looks even more implausible."

His advice: "just put your trust into the player's power of imagination. I'm sure they’ll find things wonderfully 'plausible' in ways that you never even imagined."

Another one of his tricks is underpinning the story with interesting concepts -- this keeps the player guessing and also, he says, adds a layer of believability.

For example, the AB Game explores the Prisoner's Dilemma -- which Uchikoshi describes as "fun and intriguing" -- in a concrete way, while the concept of Schrödinger's Cat, which is also toyed with, simply adds flavor to the game.

These thought experiments add a lot of flavor to Virtue's Last Reward. "However, all of things are used only to hint at things; I'm not using them to explain the mysteries and phenomena found in the story," says Uchikoshi. "Having the player personally wondering, 'Maybe the principal idea is this?' gives the story the feeling of being real and credible."

There's a line you don't want to cross, he says. These concepts are included for the player's mind to explore, not for the writer to dictate to them. "I felt that if I explained things in detail, it would sound like I was trying to come up with excuses, and the story would lose its credibility and not be convincing."

"What ultimately makes a story convincing is the player's mind," he argues. "That is the reason why I only hint at things. It is so the player can personally create the world..."

Uchikoshi also draws on ideas from other sources -- notably drawing in concepts from writers like Kurt Vonnegut and Isaac Asimov.

"My personal opinion is that 90 percent of any creative endeavor is made up of bits and pieces taken from the work of others," he says. "To overstate the point, most works today are mostly amalgamations of already existing ideas and forms."

"The question of whether what you've created is worthwhile or not depends on how skillfully you incorporated those influences with your own ideas. That is how a writer’s ability and talent is ultimately tested."

"So what comprises the remaining 10 percent? That would be creativity," Uchikoshi says; he defines "creativity" as "something that, because of your own experiences, only you can express."

"In order to fully express their creativity in that 10 percent, a person uses the influences and ideas in the other 90 percent as the foundation for their original creation. To put it simply, the process is 90 percent craftsmanship and 10 percent artistic inspiration," he concludes.

Given the high concepts that form his games, it won't be surprising to hear that story comes first for Uchikoshi -- and then the characters follow. "I extract the characters that I need to make it work," he says. This story-led style is unusual for Japan; generally Japanese creators concentrate on strong casts of characters over intricate plotting -- "as basically that is what sells."

For Uchikoshi, it's more about creating characters that serve the overall dynamic. "You create character profiles so there is an equilibrium," says Uchikoshi. "Once you set the story and come up with the characters, the next thing to do is look at the overall balance between the two.

"For example, if you make Character A's personality cold, then you would make B kind. If there's an older grandpa-type character, then you'll need to add a child. So basically you look for plus/minus, positive/negative, assertive/passive, rational/emotional."

Another important element of creating characters for a game like Virtue's Last Reward is misdirection, Uchikoshi asserts. "I deliberately throw in a character that straight-up looks like a bad person to draw the player's attention from the real antagonist," he says. "When there's a character you can vent your frustrations on, people tend to focus on that person a lot more, and it makes it more difficult to see who the bad guy really is. I learned this trick from politicians."

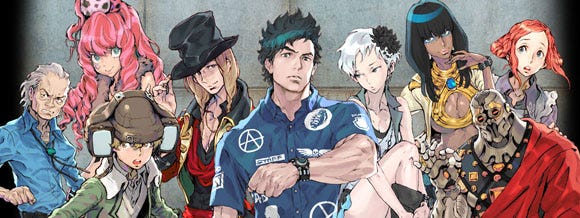

It doesn't hurt to team up with a talented artist, like Kinu Nishimura, who handled the designs for both 999 and VLR. "I think she is one of a very few designers who can make you excited about how the story will unfold with just a group shot of the nine main characters."

In the end, Uchikoshi's goal is to keep players thinking about the story -- even fixated on it. Those who have already played Virtue's Last Reward and 999 can attest to this. Whether the ideas Uchikoshi puts forward are simply interesting, or whether they form the core of the mysteries of identity and motive that rest at the center of the Nonary Game, there is plenty for your mind to play with.

Even though he's responsible for the creation of a cult hit franchise, Uchikoshi isn't yet satisfied.

"Compared to other media, I feel like fans support us feverishly. It's very humbling and I appreciate it very much," he says. "The full impact is just beginning to hit me."

Later, though, he remarks that he doesn't think the Zero Escape series can be called a "success" just yet. "For example, if you look at TV dramas such as Lost, 24, and Prison Break, those are considered to be very successful. You have to be that big to consider yourself to be successful," Uchikoshi says.

"I know you might laugh, thinking, 'Wow, you're comparing yourself to a different scale,' but with my development staff, [publisher] Aksys' help, and our fans' continued support, I feel like it's a possibility to reach that level."

"Rather than being 'a cult hit that only core players know,' we are constantly thinking how we can appeal to mainstream gamers. Therefore, if we want to make our project even bigger, we need to work on it."

Whether or not he can achieve even a tenth of this success, it's clear that his ambitions have had one effect. Uchikoshi is already pushing the boundaries of what game narrative can be.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like