Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this in-depth article, Chen looks at the state of games for social networks like Facebook & MySpace, which "seem poised to set a revolution in the game industry akin to the one first kindled by downloadable casual games", according to her.

With over 200 million people registered on Facebook, the most popular social networking site, and millions, millions more on similar sites like MySpace, Bebo, and Hi5, social networking has become a part of daily life.

As quoted in the Financial Times, one CIO of a leading U.S. firm found that her young employees "communicate by Facebook and simply will not read their e-mail." Worldwide, social activists are using social networking sites to organize protests. Meanwhile, others have found old classmates and friends using these sites. It's a testament to the power of social networking.

Likewise, social games -- essentially games created to be playable within existing major social networking websites -- seem poised to set a revolution in the game industry akin to the one first kindled by downloadable casual games. These games that use social connections have multiplied like wildfire on social networking sites.

They represent a viable business opportunity for game developers and venture capitalists agree, investing approximately $98 million in social game companies last year. It's no surprise that mobile game developers, casual game developers, and web programmers are forging ahead with social games. Even EA has a Facebook game.

Additionally, with a mixture of business models, social games offer game developers a test bed to see user reactions. Most importantly, because the sales are direct-to-customer, game developers own the customer relationship.

Using customer data supplied directly by Facebook or other sites, they can more fully understand customer needs and in turn, engender customer loyalty. As such, these developers follow in the steps of successful companies like 7-Eleven Japan, which uses its customer behavioral data to forecast exactly needed inventories.

While social games do not seem to have realized such accuracy as of yet, the potential for moneymaking remains strong. The Facebook platform, which was the first, launched in April 2007 and within weeks, entrepreneur Suleman Ali had a hit application and was generating enough revenue through advertising to hire employees.

He eventually sold his company Esgut and its roster of games to Social Gaming Network (SGN) in April 2008. Nowadays, the big players in the social game space are Playfish, Zynga, and SGN. All of Playfish's games are in Facebook's Top 25 whereas Zynga clearly dominates the MySpace charts.

While some consolidation in the sector is to be expected, a one-man shop is still a possibility. Entry costs are low and viral distribution over the Facebook platform reaches over 200 million potential users. That staggering amount,

Gareth Davis, Platform Program Manager at Facebook, enthusiastically points out, exceeds the total number of users for World of Warcraft and Xbox Live combined. In fact, the number of users World of Warcraft has collected over four or five years is equal to the number of new sign-ups to Facebook each month.

If this data isn't compelling enough, keep in mind that even before this population spurt, SGN's early Facebook game, Warbook, pulled in about $100K a month in its heyday. Facebook itself is estimated to have revenues of $50 to $70 million from its virtual gift sales (currently at $1 to $50 each) for last year. So, even if the games on social networking sites are simplistic compared to AAA titles, they are worth noting, especially since they have the power of social networking behind them.

But what exactly are social games? Like "casual games," the term is supposed to describe a specific market segment. Most games are already social, though, in that we play them with others or we participate in the communities that have built up around them. What makes social games different?

Colloquially, games on social networking sites and/or on iPhone are called social games, but even this definition is up for debate. Some differing definitions or conditions include:

Multiplayer games that utilize the social graph, i.e. a player's social connections, as part of the game. Examples: Parking Wars, PackRat

Games in which the main gameplay involves socializing or social activities like chatting, trading, or flirting. Examples: YoVille, Pet Society

Turn-based games that are played within a social context or with friends. Examples: Texas Hold'em Poker, Scrabble

Competitive casual games that include friends-only leaderboards. Examples: Who Has the Biggest Brain?, Word Challenge

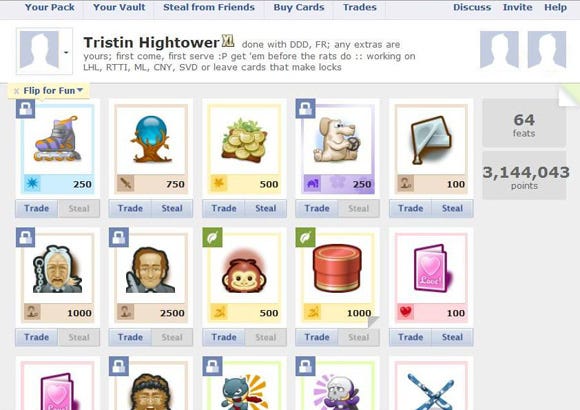

PackRat

Very clearly, some social games are ports or variants of existing casual games. Demographically speaking, women over 55 are the fastest growing segment on Facebook.

The latest study from search service firm Rapleaf shows that with the exception of LinkedIn and Flickr, women outnumber men in all age groups across all social networks, so it would make sense that casual games flourish on these sites. Are social games just casual games transplanted to social networking sites? Not quite.

Firstly, not all social games are considered casual games. They're called hardcore or casual based on gameplay. A strategy-based game like Warbook draws the same typical hardcore crowd of young males whereas the virtual pet simulation, (fluff)Friends, also from SGN, is popular among women, ages 24 - 40.

So does the platform make all the difference? Partially. I would say one difference lies in social psychology. "There are nuances that you have to understand to do well on Facebook," warns Ali. Playing online games with friends has a different dynamic than playing with strangers.

Even a zero-sum collection game like PackRat, in which players steal cards from friends, has been turned around by the desire of players to play cooperatively. Do you dare risk your friend's anger by stealing a much-needed card? People act differently when there's shared history.

Furthermore, unlike on MMOs or casual game portals, people don't tend make new friends on social games. They've already got an established network of friends and acquaintances. Instead, this type of socializing cements existing ones. The average Facebook user has 120 friends, but would not consider them to be all close, personal friendships. Social networking sites join "weak ties," people like high school classmates and old work buddies, and encourage what psychologists call parasocial relationships. You observe snippets of people's lives, but do you really know them? For deep relationships, it seems, you still need to put in the face time and have shared experiences.

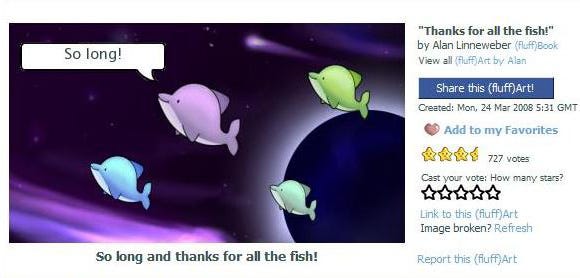

(fluff)Friends

Exceptions exist, mainly in virtual pet and virtual world simulations like (fluff)Friends and YoVille. (fluff)Friends has even had a (fluff)Con for Fluff Fanatics. Lately, (fluff)Friends has been holding (fluff)Art contests, which appeal to users' creativity, but even without these contests, the (fluff)Friends community would still eagerly upload fluff(Art) for peer ratings a la YouTube or Flickr. These activities fulfill a basic human desire for approval, self-expression, and recognition.

In fact, these human desires may be heightened when interacting with friends rather than strangers. Emotions such as competitiveness, affection, love, envy, and pride are what Playfish calls "social emotions."

"Social emotions form the basic building blocks in each of our games," says Kim Daniel Arthur, VP of Global Studios at Playfish. "This requires a new way of designing and thinking about games, from simple elements such as our friends score bars in Word Challenge to the more intricate social interactions in Pet Society." For Playfish, the social experience of a game is the primary focus.

Again, look to social psychology as to why social comparison and friend-trading games exist alongside RPGs, virtual worlds, strategy games, and casual games on social networking sites.

Bragging rights and the need for social status are a big part of this landscape, especially when a person's every move is recorded by Facebook's continual newsfeed of updates, links, videos, photos, activities, purchasing habits, game scores, likes/dislikes, and even recipe selections. "Social games are communication tools," says Shervin Pishevar, founder and CEO of SGN. "That's why they do well in a massive communication network like MySpace or Facebook."

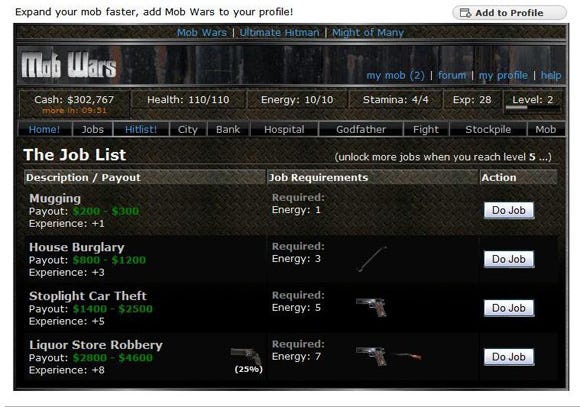

Other games, such as the Facebook RPG Mob Wars, are stripped-down versions of PC or console games. Although an RPG, Mob Wars is a game without gameplay, in a way, because the gameplay is replaced by a button click of "Do Job." It's as if every player had a Glider autopilot program to go out and kill mobs. However, the strategic elements of deciding which task to do first and inventory management remain intact.

Tom Abernathy, Writer at Microsoft Game Studios, remarks, "It's a serviceable but not exceptional little bare bones RPG. But I can play it while I'm doing other things."

This type of passive play, called sporadic play, and asynchronous or turn-based play, says social game blogger Bret Terrill, now Director of Business Development at Zynga, is critical to the success of social games. While not prevalent on casual game portals, passive play is common on social networking sites.

However, Playfish's Who Has the Biggest Brain? and Word Challenge are basically short single-player games. Launched in December 2007 as Playfish's first title, Who Has the Biggest Brain? seems to have a permanent lock in the Top 10 of Facebook games.

For now, there doesn't seem to be a unifying characteristic among all of these games, other than they exist on social networking sites. However, I would posit that there are certain design characteristics that could make social games a unique category.

Social networking sites have changed how we consume information and how we play games. It is only fitting that social games reflect the characteristics of the platform. When combined together, the social graph, ambient awareness, and inclusive play are the design characteristics that make social games distinctive to me.

While new initiatives like Facebook Connect and MySpace Data Availability will allow these applications to run outside of social networking sites, these defining characteristics are not affected due to data portability.

Social Graph

Looking back to the proposed definitions in the previous section, there is one that does describe games that cannot be played anywhere else without data portability. These are games that utilize the social graph.

Most games do pull data from the social graph for challenges and friends-only leaderboards, but some go further by incorporating the social graph into gameplay. In Parking Wars, I can park on each friend's street and in PackRat, I can browse through my friends' pages.

In order to do well in Parking Wars, I need to know the usage patterns of my friends. I find that these games have the camaraderie of a board game, in that there are conversations about the game among friends, and yet, it's not necessary for all my friends to be online at the same time to play the game.

In theory, any sort of information, like fave bands or travel photos, can be pulled from people's profiles, much like Facebook ads do on the side. Ideally, these games would require people to know something about their friends to do well. Or at least, by playing the game, people would end up knowing more about their friends.

Ambient Awareness

On social networking sites, information flows at a rapid pace. The Facebook newsfeed is filled with information no one would ever write an e-mail about or call to tell a friend. Each piece of information is trivial -- e.g. "Facebook User made a ham sandwich." -- but taken in aggregate, all of it coalesces to form a daily picture of what's going on in the lives of friends.

This clutter of unfettered information leads to what social scientists call "ambient awareness." It's similar to noticing what others are doing in a room without even paying attention to them.

Each bit of information accumulates and without even noticing, you learn that two of your friends were in train wrecks, five have the same birthday, or three are attending a conference in Japan. Unwittingly, people's personal lives are scattered across applications, walls, forums, status updates, notes, and comments. Concurrent or parallel conversations are the norm.

Similarly, if I have ambient awareness in a game, it means that just by playing, I'm aware of my friends' progress in the game. I don't need to search for this information. For example, in PackRat, since I have to cycle through my friends' pages, I see their cards and activity logs.

If I've already gone through that set, then I know exactly which cards they need to complete the set. If I want to learn more, then I can click on my friends' Feats, which are similar to Xbox Live achievements or Pogo badges. As a side benefit, by creating these achievements or checkpoints, the developer can collect and analyze valuable customer data to improve the game.

Inclusive Play

The average user belongs to more than one social networking site, but devotes the majority of time to only one. As such, users have different participatory rates, logging in to one social network every day, another every once in a while, and yet another, only if an e-mail beckons the user to come back.

These different participatory rates translate into different play patterns. Some players have limited time and need a game that can be played quickly whereas others are willing to spend hours on a game. In fact, depending on the day or the social networking site selected, the same user may exhibit different play patterns. Therefore, it's more useful to divide players by play patterns rather than by gender or age. A game with inclusive play satisfies players who want to play sporadically and/or continually.

Obviously, real-time multiplayer social games have an issue if there are not enough friends online to play the game. By continual play, I simply mean that the game provides something meaningful for the player to do to further the experience. If I have more than 1 minute to play a game, then I should be allowed to continue.

Instead, in a game like Dungeons & Dragons: Tiny Adventures, I'm forced to wait. Sporadic play is great for multitasking but if you're not multitasking, then the game gives you no other choices to occupy your time. Decisions made with a button click, such as rearranging inventory, applying abilities, or applying potions, rarely take six minutes.

MMO consultant Brian Green agrees, "The game requires almost no meaningful input on the part of the player. It's mostly about coming back on the proper schedule and clicking a button to see what happened."

Mob Wars

In Mob Wars, the waiting period is required to regain energy. It's patterned after MMORPGs when a player needs to regenerate mana and health. However, in a MMORPG, a player can do something else to get XP without expending a lot of mana and health.

Just like "dead air" is anathema to radio, so too is any time the player is sitting around with absolutely nothing to do in a game, and that is, nothing, not even a look at pretty pictures. There is also the danger that the player may leave and forget to return to the game.

Much as sporadic play appeals to one player type, it doesn't work for everyone. Asynchronous play, however, fares better with its long history in games. War games such as chess have been fought via postal mail and then on e-mail and mobile phones. Players have an understanding of how asynchronous games work. Still, I have seen Scrabulous games fall apart due to lack of response. The notion that players have to come back to a game because it's sporadic or asynchronous is a hollow one.

Games built with inclusive play in mind allow all player types to enjoy the game regardless of whether they have 10 seconds, 10 minutes, or 10 hours to play the game. Most casual games fit this model because a player can keep on playing the same short "coffee break" game continually.

The player gets better at the game and perhaps unlocks achievements, but it would be nicer if there was a deeper experience. Other genres, like virtual worlds, RPGs, and strategy games, can certainly take advantage of this design philosophy.

Although the development cycle of social games is similar to that of casual games, their business models are more aligned with MMOs. Given their origins, however, social games almost always have a free component. Beyond that, game developers are free to monetize applications as they see fit and they've been doing well with a mixture of the following business models:

Advertising or Sponsorship

Microtransactions: virtual currency and/or virtual goods

Subscriptions or Premium modes

The advantages for developers for using a social network like Facebook are evident. The barriers to entry are low but the potential for profit is high. They're getting wide distribution on a trusted network and moreover, they don't need to share revenue with Facebook.

The approval for Facebook applications is quick -- something like 24 hours from submission. Ali built his first app in two weeks, but nowadays, with better graphics and production values expected, it might take three to six months for an application to go online.

Even after a game goes live, social game developers must maintain the service and answer to customers. Like MMO developers, social game developers are constantly adding content and evolving their games. Compared to MMOs, though, these iterations occur at a blistering pace.

"Facebook time is faster than normal Internet time," says Ali. "Facebook enables rapid feedback in a way that the Web never did before."

As such, clones of games run rampant, but the first mover may not have the advantage as other developers improve upon the design. The friend-trading stock market game, Friends for Sale, for instance, was preceded by Owned! and Owned! in turn was preceded by Human Pets. Mobsters, Mob Wars, and Mafia Wars are all similar takes on a RPG.

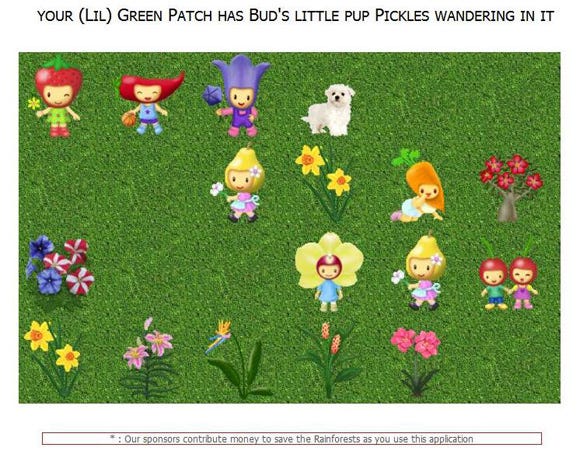

Some developers also sweeten their app's sales by appealing to users' charitable natures. (Lil) Green Patch, a top Facebook virtual pet application, purports to help save the rainforest while you tend to your garden and scare off pests.

Numerous other apps of this kind exist, some with ties to charities like the Nature Conservancy. The causes supported range from world hunger to global warming. It's unknown how much of this revenue actually goes to the charities. A few users from the IGDA Women in Games mailing list reported that by playing these games every day or by buying the game's virtual currency, they felt that they were assisting a valuable cause.

(Lil) Green Patch

Because these business models do better when there are more users, some developers had "forced invites" built into the application. If users wanted to progress in the game, then they needed to invite friends to add the application. "The days of Facebook games after the API was introduced were horrible for a lot of people," says Green, "because of the constant spamming by your friends to join some new game."

In February 2008, Facebook banned forced invites, which has led developers down creative routes to incentivize invites in game design or otherwise, use newsfeed notifications to their advantage. Both SGN and Playfish steadfastly avoid spamming, instead relying on word of mouth for their games.

Playfish is experimenting with all three business models and has been successful in monetizing these multiple revenue streams. Overall, Ali estimates that 80% of revenue for games comes from virtual currency whereas 80% of revenue for non-games comes from advertising or sponsorship.

Advertising/Sponsorship

The game developer can place interstitial ads, banner ads, video ads, links, or branded virtual items inside the game. Most advertisers are looking for an application that will integrate their brands into the game. This hasn't happened as much in games, but can with the help of 3rd party ad networks like AppSavvy, SocialMedia.com, and Cubics. Else, the game developer can sell ads or get sponsorship on its own.

Developers can also use networks like Super Rewards and Offerpal Media to receive a referral fee. In exchange for filling out offers to join NetFlix or other services, players receive virtual currency or goods. (Lil) Green Patch, for example, offers more acreage for your garden if you sign up for a number of offers.

Microtransactions

In most cases, developers use a dual currency system. In (fluff)Friends, there's munny and there's gold. Munny is earned while playing the game and can be used to purchase virtual goods to pamper your (fluff)Friend. Gold, however, is used to purchase limited edition characters, merchandise that simply isn't available to those with just munny. To obtain virtual currency like gold, players pay for it with PayPal or credit cards. Across Facebook, virtual items range in price, from $1 to $50.

As in the case with free-to-play MMOs with microtransactions, developers must be careful to keep these special items from unbalancing the game. It's important that non-paying players enjoy the game as much as paying players. For games like (fluff)Friends, it's definitely more fun with more players. Developers need to take care not to alienate non-paying players.

Subscriptions/Premium Modes

In the subscription or premium mode scenarios, players pay a monthly or yearly fee for extra modes or advantages. In Word Challenge, a player can pay for Pro Player Club membership and get more taunts, no ads, and exclusive modes of play, like Word Grid. Again, the issue here is whether or not the premium mode unbalances the game or gives subscribers an unfair advantage. In the case of Word Challenge, it doesn't.

In PackRat, though, the subscription definitely gives an advantage to XL (premium) players by giving XL players access to XL markets, double pack size, and tix, the PackRat equivalent of (fluff)Friends gold.

Although these perks are understandable because XL players want value for their subscription, it has slowed down the game considerably. With the extra pack size, XL players, whether intentionally or unintentionally, hoard cards and remove them from circulation. This was more apparent in PackRat v2.0, which has since been dismantled.

While the first generation of social games had simplistic gameplay and simplistic graphics, the second generation has upped the ante. Production values match Web games and game developers are merging the gameplay qualities of casual games, MMOGs, and virtual worlds. With Flash 10's 3D capabilities, 3D games may be coming to social networking sites soon.

"The sky's the limit," says Davis.

One day in the future, players will enjoy immersive strategy games, arcade games, casual games, RPGs, ARGs, and virtual worlds, all on a social networking site. Davis fully expects larger game publishers to join the fray and make this vision a reality.

As for indie developers, Ali, now a partner at Shotput Ventures, says, "Just do it. There are so many stories of people who are building an app for Facebook and it ends up being such a great success that they quit their day job. It's totally possible."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like